Bharatmala project: Roadblocks ahead, expect delays

Land acquisition and lack of funding hold up work as government barely meets a quarter of its target under the Bharatmala project ahead of its 2022 deadline

The Dwarka Expressway, connecting Delhi and Gurugram, was expected to be completed by 2012, but has been delayed because of land acquisition issues

The Dwarka Expressway, connecting Delhi and Gurugram, was expected to be completed by 2012, but has been delayed because of land acquisition issues

Image: Vinay Gupta[br]Like the economy, highway construction seems to have hit a slowdown. Halfway through the 2022 deadline of the government’s ambitious Bharatamala Pariyojana, only 27 percent of project contracts have been awarded, according to credit rating agency ICRA.

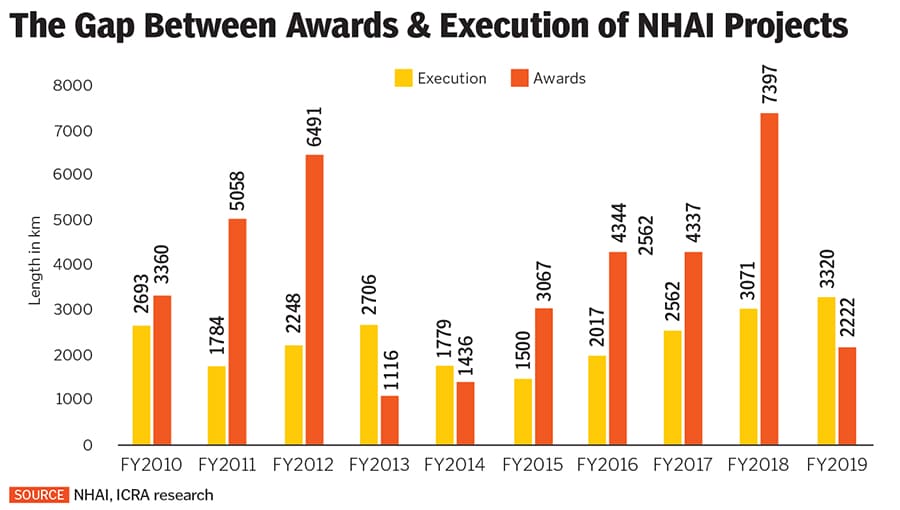

Bharatmala is a central government scheme to build highways, cleared by the Union Cabinet on October 25, 2017. It aims to complete Phase I—24,800 km of fresh roads and 10,000 km of roads subsumed from the National Highways Development Project—by 2022, at a cost of ₹5.35 lakh crore. However, by September 2019 contracts for only 9,577 km of the 34,800 km had been awarded. Rajeshwar Burla, vice president, associate head-corporate ratings, ICRA, says, “Ideally, the government should have awarded everything by now because it takes at least 2 to 2.5 years to complete a road project.”

What are the roadblocks that the government have hit? First, land acquisition that can cost at least 25 to 30 percent of every project there can be projects where it is even higher than the cost of construction. It not only escalates overall project costs, but also causes enormous delays.

VK Sharma, chief general manager, land acquisition, National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) writes in the September 2019 issue of the magazine Indian Infrastructure: “In a study conducted by NHAI on 106 projects, worth over ₹1.5 billion, facing implementation delays, issues pertaining to land acquisition were identified as one of the important causes for the delay in almost 50 percent of the projects. Besides, about 5 percent of these projects were delayed exclusively because of land acquisition issues.”

The government’s burden to acquire land has risen in compliance with the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, that mandates it to pay four times the market value of acquired land in rural areas and two times in urban areas. Rohan Suryavanshi, head-strategy and planning at Dilip Buildcon, a road construction company, says, “Before 2013, people didn’t want to part with land. Now, they are willing because of the generous compensation.” Sharma says in Indian Infrastructure that the NHAI has been able to get about 13,982 hectares in 2018-19, the highest in the past 18 to 19 years. But, according to ICRA, the average cost of acquisition has gone up from ₹0.9 crore per hectare to ₹3.4 crore per hectare the awarding cost of contracts has, therefore, gone up from the initial plans of ₹15.37 crore per km to ₹24 crore per km.[br]While costs have risen, financing has nosedived. “Historically, banks were the main source of finance for infrastructure projects. But they have constraints in providing long-term finance as it leads to significant asset liability mismatches,” says Debabrata Mukherjee, head-business at NIIF Infrastructure Finance Limited. While earlier development financial institutions funded infrastructure projects, they have now turned into commercial banks and are suffering from the stresses that the banking ecosystem is facing.

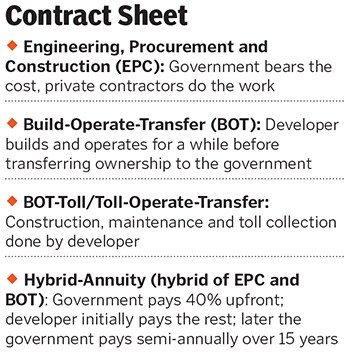

There are other challenges too. It is mandatory to acquire 80 percent of land before a project starts the mandated amount of land is 90 percent in engineering, procurement and construction projects (EPC) projects. Environment clearances also pose a hurdle, like with the ₹1,850 crore Char Dhaam project.

To fund its projects, the NHAI also needs to complete and operate projects so that they are monetised. Says Burla, “The progress on monetisation has not been as it was envisaged. In this context, the recent decision by the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs that authorised NHAI to set up an Infrastructure Investment Trust (InvIT), a first from a central public sector enterprise, is a positive.”

The difficulty in raising funds from completed projects is increasing NHAI"s reliance on borrowings these have risen by more than 2.4 times in the past two years, from ₹75,385 crore as on March 31, 2017 to ₹1.79 lakh crore as on March 31, 2019. It is expected to double by FY22.

Mukherjee says, “Earlier, NHAI funded most of its projects through the BOT model under public-private-partnerships. Apart from land, it didn’t have any other significant costs. Of late there has a been steep rise in land costs, leading to higher debt.” Officials from the NHAI or the Ministry of Road and Transport did not respond to Forbes India queries. Adds Burla, “Since October 2017, 90 to 92 percent of projects have been awarded via either EPC or HAM route (see box). Less than 10 percent were awarded through BOT-Toll route. As a result, the financial burden on the government is high.”

The government needs to award more projects via the TOT model instead of the EPC or HAM models. TOT projects have seen the interest of a lot of Indian developers tying up with foreign funds. In the three Bharatmala projects auctioned under the TOT model, where the first and the third have been successful, the trend is to tap the financial muscle of foreign funds and the operational capabilities of local developers.

The government could also try and bundle under the BOT programme projects where land acquisition and environmental clearances are not a big challenge. The trend for BOT projects have changed, explains Mukherjee. “When the road development programmes started in the late 1990s and early 2000s, many developers queued up to bid under BOT. But many of them suffered badly as they were unable to handle risks as they had aggressively bid for these projects based on optimistic traffic projections, leading to overleveraging of their balance sheets.”For any infrastructure funding, the new key source is InvITs, where investors can purchase units of a portfolio of completed infrastructure assets. While today we see more private InvITs than public ones, NHAI has the government’s nod to set up its own. Importantly, NHAI will have to be conscious of the asset selection as the InvIT portfolio will drive investor interest.

NHAI will release partial payments to highway builders for their work, even if they don’t achieve a milestone. This will ease the path for developers as working capital advance is aimed at completing projects and providing liquidity.

The government’s fight with debt will increase their expectations from the upcoming Budget, but given the economic conditions, allocations might not meet expectations. Thus, as long as funding is concerned, the government will have to look for other sources. Mukherjee says, “Project selection and structuring are key to success. Projects in high-traffic corridors that are awarded with better preparedness will have higher probability of getting funded.”

First Published: Jan 21, 2020, 12:46

Subscribe Now