Budget 2016: Decoding the FM's dilemmas

Budget 2016 will be announced 25 years after India embraced economic liberalisation. The historic import will not make Arun Jaitley's already cumbersome task any easier

On July 24, 1991, when Manmohan Singh, then finance minister (FM) of India, rose to present the ‘historic’ budget, the Indian economy was tottering. Foreign exchange reserves, at less than $1 billion, were barely enough to cover a few weeks of imports and the country was on the verge of defaulting on its debt obligations. India’s short-term foreign debt (due for repayment in less than a year) stood at $13.6 billion while total forex reserves (including gold) totalled just $5.8 billion. The country had already suffered the ignominy of pledging its gold reserves to raise foreign loans to tide over the immediate crisis. The oil shock after the August 1990 Gulf War (oil prices tripled during this period), and two years of political instability, had left India facing its worst financial crisis in its post-Independence history. Though the $250 billion economy was growing at 5 percent, inflation was running amok (it touched a peak of 16.7 percent in August 1991), fiscal deficit was over 8 percent of the GDP and the rupee, pegged at Rs 14 a dollar, left exports wholly uncompetitive.

The Congress government led by PV Narasimha Rao, which came to power in June 1991, had devalued the rupee by 18 percent and announced a new export-friendly trade policy. The world expected a lot from Singh’s maiden budget. And he did not disappoint.

Singh charted a new course by exposing the controlled Indian economy to market forces. The liberalisation he unleashed ended License Raj, allowing industry to add capacity based on market demand and supply, opened up the economy to foreign competition by reducing import duties and took steps to rein in the unsustainable fiscal deficit by increasing the prices of petrol, diesel, kerosene, LPG and fertilisers. The Opposition accused the government of selling out to the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. But, barring a minor rollback in fertiliser prices, Singh managed to get his budget proposals through Parliament.

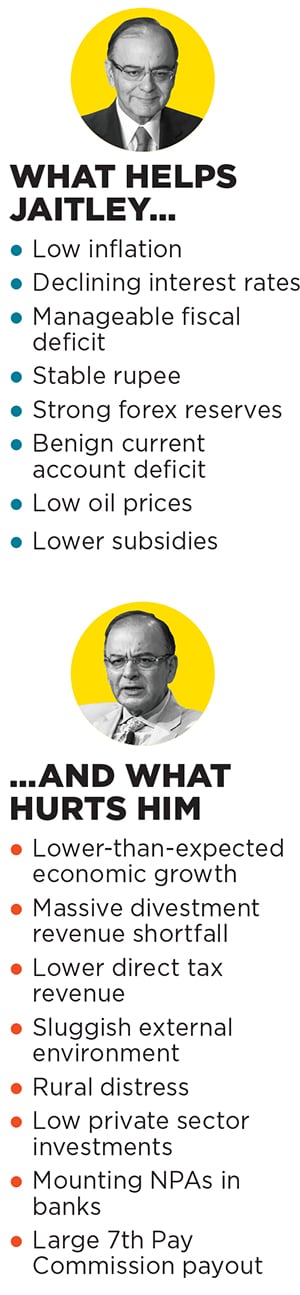

Twenty-five years on, when incumbent FM Arun Jaitley rises to present the 2016 Union Budget on February 29, the now $2 trillion Indian economy is in a sweet spot with strong macro-economic parameters. Inflation is low at less than 6 percent, interest rates are falling, fiscal deficit (3.9 percent) is manageable, the rupee is stable (compared to other emerging market currencies) and forex reserves are comfortable at $349 billion. Despite headwinds in the form of a sluggish external environment, India grew at 7.2 percent in 2014-15 (as per the Central Statistics Office) and is expected to grow at 7.6 percent in 2015-16. In fact, last year, the Indian economy has achieved the distinction of becoming the fastest growing major economy in the world.

These favourable conditions, however, do not make Jaitley’s job any easier. The public and industry both expected the Narendra Modi-led NDA government, which came to power in 2014, to quickly accelerate the economy and usher in the promised ‘achhe din’. That it is still work in progress has proven to be frustrating. “This is a very important Budget. The Modi government should get the resource allocation and execution right. It is almost two years into this government and it cannot be talk, talk and talk. You cannot blame the Opposition for all the challenges,” says Vijay Govindarajan, the Coxe Distinguished Professor at Tuck School of Business in the US, and a keen India watcher. The government’s pro-growth credentials are at stake like never before. About 96 percent of the CEOs and CFOs surveyed in the Forbes India-BMR Advisors Pre-Budget Poll have said that Budget 2016 will be very important in strengthening the government’s pro-growth image.

If, in 1991, the world expected Manmohan Singh to show that India had the wherewithal to overcome its financial crisis, it now expects Jaitley to lay down a clear roadmap to take the Indian economy to the next level of growth.

But it is in this that the FM faces many a dilemma.

Dilemma 1: Public Investment vs Fiscal consolidation

In last year’s Budget, Jaitley deferred the fiscal consolidation roadmap by a year and used the resources so released to boost public investment in infrastructure by Rs 70,000 crore. Consequently, resources were pumped into roads, urban development and railways. As of last November, spending in the road sector rose by 63 percent, urban development by 31 percent and railways by 12 percent.

In the run-up to this year’s Budget, the chorus for doing an ‘encore’ to up public spending at the cost of fiscal consolidation has reached high decibel levels. Reason: Despite last year’s public investment boost, the overall investment as a share of the GDP stood at just 31.2 percent in the first six months of the current fiscal (2015-16) as against 38.6 percent in 2007-08 when the investment cycle peaked.

Proponents of public investment, such as Dani Rodrik, professor of International Political Economy at Harvard University, use this data, and the fact that two other engines of growth—exports and private investment—are not delivering, and consequently holding back the economy. Exports are expected to decline by 13 percent this fiscal and private sector investment as a share of GDP has gone down from 17.3 percent in 2007-08 to 12.6 percent in 2013-14. “In the current state of our economic cycle, public investment will crowd in private investment,” says Ajit Ranade, chief economist at Aditya Birla Group.

Differences of opinion have emerged on whether it should be at the cost of fiscal consolidation. “It is important for us to send the right signal about our commitment to fiscal prudence,” says Ranade. Samiran Chakraborty, chief economist-India at Citibank, agrees. “We cannot be delaying it every year. We will lose our credibility,” he says.

Reserve Bank of India Governor Raghuram Rajan waded into this debate while delivering the 4th CD Deshmukh Memorial Lecture and urged the government to stay on the path of fiscal consolidation. “The consolidated fiscal deficit of the states and Centre in India is by far the largest among countries we like to compare ourselves with presently only Brazil, a country in difficulty, rivals us on the measure,” he had said.

But a majority of the 30 economists that Reuters polled recently preferred higher public spending even if it means a slight slippage in reaching the fiscal deficit target of 3 percent of GDP. Rodrik recently argued in a newspaper article that “if public investment serves to accumulate instead of spending on salaries and subsidies it is a viable growth strategy in a hostile global economic environment”. Even rating agencies Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s have said that India’s sovereign rating will not be affected if the government steps up public spending and defers fiscal deficit targets.

What they have not indicated is how far the government can go. “Considering that the fiscal multipliers in the economy are presently low, public investment will crowd in private investment only if the quantum of investment is large,” says Chakraborty. “That means government deviating from its fiscal target by a large margin.” Such a move could push up market-linked interest rates resulting in a capital outflow from portfolio investments in government and corporate debt (which stands at $60 billion) apart from triggering a rating downgrade. India is currently at the lowest notch of investment grade.

Dilemma 2: Reviving private investment using fiscal incentives vs Conserving resources

Jaitley had recently said that he will focus on reviving private investment. “Any economy needs multiple engines of growth,” he had emphasised. Now, economists expect him to offer fiscal incentives. But will that work?

Consider that private sector investment has declined for many reasons. Domestic demand has been low, with no clear signals of revival. Industry typically looks at a five-to 10-year outlook for making an investment decision. Exports have also been declining. All these factors have left industry with low capacity utilisation (below 75 percent). Also, companies have been squeezing their assets more effectively in recent months and that is reflecting in higher operating margins. According to Morgan Stanley Research, operating margins of companies are approaching an all-time high and are at 27.5 percent. That apart, corporates are over-leveraged. Private sector debt at present equals 70 percent of GDP, compared to 40 percent when the investment cycle picked up in 2004-05. Then there is the issue of high interest rates.

The Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) that India has signed with many of its trading partners are also thwarting a revival in private sector investment. Take the steel sector, for instance. Import of finished steel rose by 7 percent in 2014-15 and 30 percent in 2015-16, taking advantage of zero or negligible duties. Today, imports account for 15 percent of India’s demand, while capacity utilisation is under 80 percent.

From a global perspective, FTAs have an impact in other ways too: Under FTAs, it makes sense to manufacture in the most efficient region, and export. But tax anomalies in India complicate matters. “While SEZs are offered tax benefits for exports, they have to pay duties for sales within India. This makes importing from another country cheaper,” says Ranade. “India must first sign FTAs with its SEZs.”

Considering these issues, offering fiscal incentives may be akin to throwing good money after bad Jaitley could instead focus on improving the ease of doing business, help companies deleverage their debt and finance stalled projects.

Dilemma 3: Boosting consumption vs Encouraging savings

Boosting consumption is one way to get the industry to utilise excess capacity and start investing. Jaitley could choose to use this strategy to convert some of his challenges into opportunities.  The 7th Pay Commission will entail an outflow of Rs 1 lakh crore (if all recommendations are accepted), and One Rank One Pension (OROP) another Rs 20,000 crore. Jaitely could disburse this money such that people can spend more, thus boosting demand. Expectations are also high about Jaitley tweaking the personal tax structure: Increasing the threshold level of income tax, 80C benefits and the limit of interest on housing loan available for deduction. The tax sops, said Adi Godrej, while participating in the Forbes India CEO Dialogues on pre-budget expectations (page 48), will be revenue-neutral as the resources that the government foregoes will come back as indirect taxes.

The 7th Pay Commission will entail an outflow of Rs 1 lakh crore (if all recommendations are accepted), and One Rank One Pension (OROP) another Rs 20,000 crore. Jaitely could disburse this money such that people can spend more, thus boosting demand. Expectations are also high about Jaitley tweaking the personal tax structure: Increasing the threshold level of income tax, 80C benefits and the limit of interest on housing loan available for deduction. The tax sops, said Adi Godrej, while participating in the Forbes India CEO Dialogues on pre-budget expectations (page 48), will be revenue-neutral as the resources that the government foregoes will come back as indirect taxes.

But will people spend the largesse? RBI’s Consumer Confidence Survey (September 2015) indicates that current and, more importantly, future expectations on income and spending (especially on non-essential items) has declined. Experts attribute the weakness in consumer confidence to a poor job outlook. The Labour Bureau’s quarterly employment data nails this fact. It reveals that job creation picked up substantially across eight employment-intensive sectors after the Modi government came to power—4.57 lakh jobs were created in the first nine months—but has since slowed down significantly. The first quarter of 2015-16 even saw job losses. Also, the rural economy, which accounts for 55 percent of overall demand, is in distress after two consecutive monsoon failures.

Another way for Jaitley to boost consumption is to create conditions for interest rates to decline, which could then fuel demand. Here, too, he has to be careful as a fall in interest rates (like in the case of boosting consumption) will affect savings. The government has been working hard to channelise savings from physical assets, such as land and gold, to long-term financial instruments, which can then be used to fund infrastructure development. This is critical as public-private partnership (PPP)in the infrastructure sector is not picking up. If interest rates fall too sharply, the shift to physical assets will rise.

Dilemma 4: Recapitalising banks vs Taking NPAs headlong

One of the reasons why banks are not reducing interest rates charged to customers is the delinquency rate. According to RBI’s Fiscal Stability Report released last December, gross NPAs in the banking sector are 5.1 percent of the loan book, and stressed assets (including restructured loans) are at 11.5 percent. Public sector banks are worst hit. Their capital adequacy ratio has declined to 8.7 percent, compared to 13 percent for private sector banks. They need a capital infusion of Rs 1.8 lakh crore. The government has already announced a four-year road map to infuse Rs 70,000 crore.

Industrialists like Ajay Piramal are questioning the logic of recapitalising PSU banks without setting the house in order. “The quality of management in PSU banks has declined over time,” he said at the Forbes India CEO Dialogues. Recapitalising them now is like pouring more water in a leaky bucket, he added. He wants the government to push banks towards debt recovery by using RBI’s Strategic Debt Restructuring scheme and taking over management control. Ranade concurs that the issue needs out-of-the-box thinking. “It is time to start Bad Banks that can take over 25 or 50 top bad debts at haircut prices and then offer them to stressed asset funds that have the expertise to turn them around,” he says. “The NPA ratio is at a 13-year high. There is no chance it will go away without drastic measures.”

Taking on bad debts headlong will work but it is time-consuming. PSU banks, on the other hand, need funds quickly as their ability to lend is being impaired and, in turn, starving the economy of funds needed for growth.

Dilemma 5: Incentivising exports vs Rupee depreciation

Exports have taken a beating, with merchandise exports declining for the 13th straight month and overall exports expected to decline by 13 percent in 2015-16, from $270 billion registered in 2014-15. Not surprisingly, the clamour for export incentives has grown.

Suranjan Gupta, additional executive director, Engineering Exports Promotion Council, says export incentives have to be given to prevent a further fall in exports. “China has been doing all it can to boost exports. It has removed export taxes, reduced export prices and devalued the yuan,” he says.

But is it the right time to offer incentives? The global economy is in turmoil. The IMF has reduced its forecast for global growth in 2016 from 3.6 percent to 3.4 percent. China, which grew by 6.9 percent in 2015 (the slowest in 25 years), will decelerate further to 6.3 percent in 2016. Brazil’s economy will shrink and the US will grow at 2.6 percent (slower than expected). Citibank’s Global Economic Outlook and Strategy, released in January, says that risks of global recession are rising. Export incentives may not work under these circumstances.

The other option is to allow the rupee to depreciate. Proponents of this move point out that the yuan has fallen 4 percent since August 2015, when China began devaluing its currency last year. The rupee is the strongest of the emerging market currencies, with the real effective exchange rate rising by 3.7 percent in the April-December period.

Dilemma 6: Rural distress and long-term pain vs Short-term relief

The rural sector, reeling from two consecutive monsoon failures, will get significant attention in this budget. About 302 of the 640 districts in the country have experienced deficit rainfall. Rural demand for tractors, two-wheelers and FMCG products has fallen. Poor rainfall and the lack of long-term investment in agriculture are beginning to hurt India’s food security. In January, the country imported corn for the first time in 16 years. Experts warn of more imports across foodgrains next year. The agriculture sector needs to grow at 3 percent for overall GDP to grow at 7.5 percent and much faster for double-digit growth. In the first half of the current fiscal, it grew by 2 percent. Here again, Jaitley has to weigh his options between long-term solutions and short-term gains. He can ensure a good amount of public spending in rural India by way of road and irrigation projects. Funds for improving agricultural practices will help productivity. The recently launched crop insurance should take care of future droughts.

The agriculture sector needs to grow at 3 percent for overall GDP to grow at 7.5 percent and much faster for double-digit growth. In the first half of the current fiscal, it grew by 2 percent. Here again, Jaitley has to weigh his options between long-term solutions and short-term gains. He can ensure a good amount of public spending in rural India by way of road and irrigation projects. Funds for improving agricultural practices will help productivity. The recently launched crop insurance should take care of future droughts.

The payback time for these measures is long. He could, therefore, be tempted to fire the rural sector by substantially increasing allocations under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) and raising the minimum statutory price (MSP) for various agricultural produce. This will give a quicker payback but will have side-effects. NREGA will push up rural wages without a corresponding increase in productivity, and higher MSP may fuel food inflation.

The oil windfall

This year, low oil prices and the government’s move to repeatedly raise excise duty on fuel helped earn Rs 90,000 crore of additional revenue. Ideally, this windfall should have offered Jaitley enough headroom to spend, and still meet his fiscal deficit target of 3.9 percent for 2015-16. But shortfalls of Rs 57,000 crore in divestment proceeds and Rs 40,000 crore in direct taxes have led to questions on whether he will be able to meet the deficit target.

He will and he will not, says Citibank’s Chakraborty: “In rupee terms he will meet the target and as a percentage of GDP he may not,” he explains.

For 2016-17, Jaitley has to think differently to raise more resources.

His expenditure will be more and skewed towards the 7th Pay Commission, OROP, recapitalisation of banks and the need to deal with rural distress, apart from public investment. The oil windfall will, of course, continue to be available.

He may have to exercise the option of divestment and asset sales to raise Rs 70,000 crore (SUUTI assets—government’s stake in ITC, L&T and Axis Bank—alone could fetch Rs 50,000 crore). That apart he can raise service tax (to bring it closer to the GST rate) and Swachh Bharat Cess to 1 percent from the current 0.5 percent.

Jaitley will also be evaluated on his ability to raise resources intelligently. For instance, the National Investment and Infrastructure Fund, which has a corpus of Rs 20,000 crore, can be leveraged to raise Rs 60-80,000 crore for funding infrastructure projects. Other measures: Extending the hybrid PPP model, which is successfully taking shape in the road sector (40 percent of the risk is shared by the government, which also bears the toll risk), to other sectors using NREGA to create badly needed rural assets and also finding ways to use the Rs 2.8 lakh crore surplus funds lying with public sector undertakings. Innovative ideas to tackle the bad debt problem and reviving the rural sector are critical. As Chakraborty says, “this budget will be tested for its novelty factor.”

Raising revenues apart, Jaitley needs to deliver a budget that will improve the overall sentiment.

“One of the biggest achievements of this government in the last two years is selling the India story abroad when most other economies are struggling. The government needs to deliver on what it has promised in terms of ease of doing business, tax and labour reforms, and FDI will rush in,” says Govindarajan. “Jaitley has to remember that this window of opportunity is not permanent and is closing fast.”

First Published: Feb 22, 2016, 06:26

Subscribe Now