Water Policy Draft Is Convoluted

The new water policy draft gives out contradictory signals by seeking to manage water as a community resource and, at the same time, calling it an economic good

Earlier this month, an international water summit in Bangalore that discussed private sector participation in water delivery ended on a dry note when a show-closing Water Walkathon was abandoned after anti-privatisation activists stormed the streets.

One of the protestors, Kshitij Urs of Action Aid, says the event was an “ominous sign of a slow takeover’’ by private players.

People are not fully aware of the benefits of leveraging private expertise, counters A. Ravindra, principal advisor to the chief minister of Karnataka on urban affairs and founder of the summit host, Centre for Sustainable Development. For the debate on water privatisation in India, this was Ground Zero and the timing could not have been better.

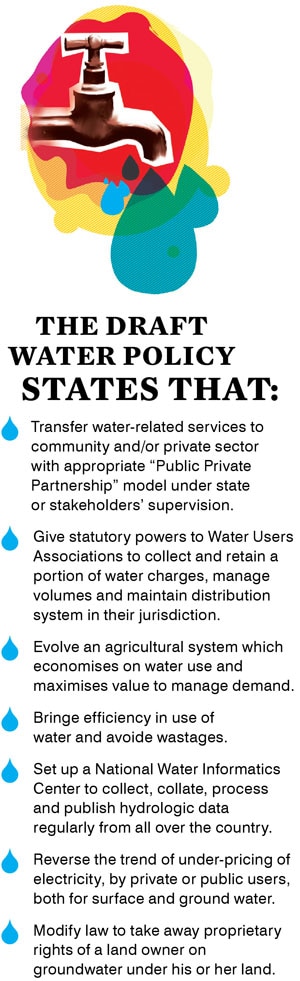

A fortnight before, the Central water resources ministry had released its draft water policy seeking a larger role for private companies in water management.

The policy seeks to manage water as a community resource held by the state under public trust doctrine to achieve food security, livelihood, and equitable and sustainable development for all.

Yet, somewhat contradicting that lofty ideal, it also calls water an economic good. The ministry wants to take away proprietary rights on water. This means no one will be able to draw groundwater without government permission even from private land.

“It is a patchwork quilt,” says former water resources secretary Ramaswamy R. Iyer. “There is no structure or coherence, no overarching perspectives.”

Iyer says the recognition of basic or lifeline water as a fundamental right did not appear to be strong in the draft. “Can we say that water is a life-right and also an economic good to be priced on full recovery basis?” he asked.

Given the sensitivity of the issue, the mood is cautious in the offices of the Union water resources ministry in Delhi.

Top ministry officials say they stand by the draft and the need for private sector participation.

“The truth is that the government’s efforts needs to be supplemented and that is why we are looking at the private sector,” says a senior official who did not wish to be identified.

The government needs a total of around Rs. 2 lakh crore just for irrigation and it cannot be met by the treasury.

“Moreover, how can you fulfil the promise of right to food unless there is water?” he asks.

India has 17 percent of the world’s population, but has only 4 percent of the world’s renewable water resources with 2.6 percent of the world’s land area. Water is a state subject and is managed by local governmants.

A 12th plan working group says the irrigation potential in India has increased from about 9.7 million hectares (mha) in 1951 to about 45.6 mha in March 2010. However, almost a fifth of the new capacities created remains unexploited.

“Privatisation is not going to solve the problems of overcoming the inefficiencies in the system. Today, only 40 percent of the water meant for irrigation actually is put to use, the rest is lost to seepage or robbery,’’ says K.J. Joy, senior fellow at Society for Participative Ecosystem Management.To study the efficiencies that private managers can bring, the government has started a pilot project with Jain Irrigation Systems Ltd.

The Jalgaon, Maharashtra-based company, which sells drip irrigation devices, would set up user-paid irrigation infrastructure in one district each of Rajasthan and Gujarat.

The state governments have agreed to provide land to the company under a private-public partnership (PPP) agreement.

The one area where supporters and opposers of the water policy converge is on the need to conserve groundwater.

The water policy wants firm laws to protect indiscriminate exploitation of groundwater and experts agree that it should be the property of the state.

Lack of regulation and indiscriminate extraction has led to a lowering of the water table and water quality problems in many regions of Punjab, Rajasthan, Haryana, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh. These six states account for half the foodgrain production in the country.

A recent report published by infrastructure financier IDFC says over 85 percent of the increase in net irrigated area between 1961 and 2001 was from groundwater sources and it now accounts for 62 percent of the total irrigated area in the country.

Yet, no agency in India has reliable data on groundwater in the country.

The country has only a tenth of the experimental wells needed to map its aquifers. There is a need to bring in efficiencies in water distribution, says Joy.

But this objective can be met by focussing on participatory irrigation management and formation of water users collectives. The policy does hint at that, but with shaky conviction.The “service provider” role of the state has to be gradually reduced and shifted to regulation and control of services.

The water-related services should be transferred to community and/or private sector with appropriate “public private partnership” model under the general superintendence of the state or the stakeholders, it says.

“That,” former secretary Iyer says, “is the thin end of the wedge towards privatisation. On the one hand, if basic water is a fundamental right, the state cannot abdicate its responsibility to ensure that it is not negated. On the other, water has to be managed at the local level with community participation. PPP is a dubious proposition.”

First Published: Feb 28, 2012, 06:53

Subscribe Now