Why Global VCs Are Running Shy

At least six international venture capitalists have scaled down or stopped investments in desi startups. But canny Indian investors are stepping in where their US counterparts fear to tread

In 2006, Canaan Partners, a global venture capitalist (VC) firm headquartered in the US, entered India with an eye on the booming early stage technology investment space. Over the past eight years, it invested nearly $200 million in 13 companies, including BharatMatrimony (matrimonial website), CarTrade.com (auto portal), Naaptol (online shopping) and iYogi (remote technical support). The investments were made from its global funds with a straightforward goal: Identify internet-based startups in health information technology, e-commerce and financial services, to name a few.

But as of 2014—in a move that echoes at least six global VC firms in India—Canaan Partners will make no new investments and has already scaled down its operations in the country.

Two of its three India team members, former managing director Alok Mittal and vice president Nishant Verman, have quit the company. Mittal, who had co-founded JobsAhead before joining the VC firm when it launched its India operations, is going back to his entrepreneurial roots and is “considering a few tech startups in the field of education and health care”. Verman has joined online retailer Flipkart as director of corporate development.

There is talk that managing director Rahul Khanna, the third member of Canaan Partners’ India team, is also exploring other avenues. The trio will, however, continue to support the firm’s existing portfolio till exits are made. Investment managers usually do not wash their hands of the investments they’ve made, and tend to see them through even after they’ve quit a firm.

Up until early this year, Canaan was evaluating the possibility of raising an India-focussed fund. “Nothing of that is happening now. Rahul [Khanna] and I decided not to raise another fund. Canaan has decided not to invest it is not motivated to build and reappoint a new team and wants to focus on its business in the US,” says Mittal. Forbes India’s emails to Marta Bulaich, vice president of marketing at Canaan Partners, went unanswered.

To date, Canaan in India has made only one partial exit—from health care firm e4e. Mittal insists that the decision to stop investments is not based on its inability to successfully exit from any of the 13 companies in its portfolio. “The focus will be on growing our existing companies we cannot unilaterally decide to exit them,” he says. But early this year, the company had identified BharatMatrimony, iYogi and UnitedLex (legal process outsourcing) as mature companies, and was looking to cut the apron strings.

Canaan’s ‘semi-retirement’ comes at a time when business sentiment has improved in India. But the VC firm seems to be in no mood to ride on the positive wave. And it’s not the only one: The Indian arms of US-based global VC companies such as Draper Fisher Jurvetson (DFJ), Sherpalo Ventures, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, Greylock Partners and Clearstone have also been gradually scaling down investments in India over the past two-three years. Summit Partners, which opened an office in Mumbai in 2012, has yet to build a portfolio.

This lack of activity is a stark contrast to the heydays of 2005-06. It wouldn’t be wrong to describe those years as a golden period of investment with millions of dollars pouring in from international investors into an economy that was growing at more than seven percent. But after 2006, the economy went through double dips of downturn and stock markets stuttered—all exacerbated by the Indian government’s policy paralysis. As new businesses struggled, the once-euphoric VCs began bearing the brunt of their own optimism.

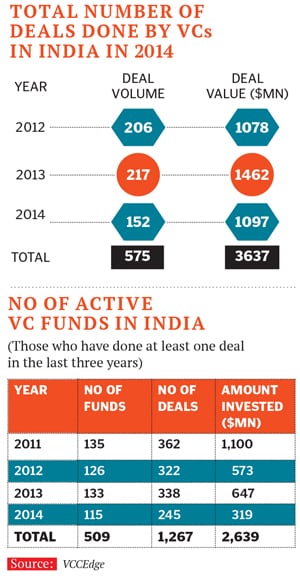

Many international VC firms seem to be following a ‘once bitten, twice shy’ India policy. The number of active funds (including those that have invested in at least one firm) in the last three years has dropped by about 18 percent, according to estimates made by VCCEdge, which tracks investment activity in the country. Analysts say it’s unlikely that the numbers will catch up before December 31, 2014.

Experts cite many reasons for this decline. For one, most international VC firms channel India investments out of a central pool of capital. A dollar invested in India will be no different from a dollar invested in the US. What’s more, an investment in any emerging economy is often expected to yield more, if not a similar, return than an investment in the US.

Quite a few VCs first invested in India nearly 8-9 years ago, but, for the most part, they have been unable to make exits. This goes against the grain because a typical fund has an investment horizon of 2-3 years. Investments in India have not returned profit for over three investment cycles. “That reality creates some amount of angst among the fund partners and also with LPs (limited partners), when, during the same time period, meaningful results have been realised in the US,” says Mohanjit Jolly, partner at DFJ, one of the VCs to have put a halt on its India investments.India has yet to make good of its potential. And because of this, there is a push from LPs (investors in VC firms) for the general partners (fund managers) to be more focussed, which usually means staying close to core countries that are yielding positive results. In this case, the US.

The US startup market is not just reviving—it is on a roll. “The thought on the part of fund managers is why go half way around the world when incredible opportunities exist in our own backyard,” says Jolly.

According to Mukul Singhal, vice president of stage agnostic investment firm SAIF Partners, global investors are seeing $1 billion exits in the US. “In that context, yes, India is not working,” says Singhal, who was part of the Canaan Partners India team, but quit in 2009.

Currency risk is another deterrent. Firms that entered India in 2005 invested when the rupee was around 43 to 45 to the dollar.

Based purely on foreign exchange—as of September 9, the rupee was 60.59 to the dollar— those early investments have lost at least 50 percent of their value. Now, companies have to grow 50 percent in Indian rupee value to return the investors’ cost basis in US dollars.

It doesn’t help that a lot of India’s rules with respect to regulatory environment, intellectual property and ethics are as clear as mud. (Successful and now famous startups such as Flipkart and redBus have grown despite these hindrances.)

And finally, other markets—China and Israel—have outpaced India. “Israel is in a different league altogether with an inherent risk-taking mindset, big vision and a direct necessary bridge to the US market. The Chinese have leveraged their closed markets and language barriers to the advantage of local companies resulting in several very large players in areas of search, mobile and e-commerce,” says Jolly.

The good news is that home-grown VC firms are going where their global counterparts fear to tread. The number of India-dedicated funds has risen from 45 to 59 in one year. This shrinkage of international players and the build-up of made-in-India VC firms are part of the evolution of the country’s investment industry, say experts.

Since January 2014, the market has witnessed more activity from seasoned Indian investors. Angel investor Rehan Yar Khan raised Rs 300 crore for his VC fund, Orios Venture Partners. Sandeep Murthy, who used to head Sherpalo Ventures and Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers in India, is raising his new $90 million Lightbox fund. It recently had its first close at $25 million. Former Infosys executives V Balakrishnan and TV Mohandas Pai promoted Exfinity Fund which made a final close at Rs 125 crore.

“Indian investors are becoming risk-takers. There is a lot of domestic capital available today and high net-worth individuals are acknowledging this asset class,” says Anil Joshi, a venture partner at the angel fund Unicorn.

Joshi claims he is not surprised with the withdrawal of global funds and believes that it is a temporary decision. “Investors can’t be completely off India’s growth opportunity. I am not surprised that they pulled back and I won’t be surprised if they come back,” he says.

For now, the promise of India holds true.

First Published: Sep 24, 2014, 06:39

Subscribe Now