Titan's wedding party

Riding on Tanishq, Titan is today the third most valuable jewel in the Tata crown. Can it get better from here?

Bhaskar Bhat, managing director, Titan, says the processes followed at the company have yielded fruitful results

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

A little before Forbes India’s interview with Bhaskar Bhat, I make the mistake of mentioning that Avenue Supermarts, which runs the supermarket chain DMart, is India’s most profitable retail company. Only to be swiftly corrected. “People tend to forget that Titan is also a retail company,” he explains with absolutely no hint of annoyance. “More profitable and more valuable!”

Bhat’s rejoinder sets the tone for the quiet self-assurance with which he fields questions. And why not?

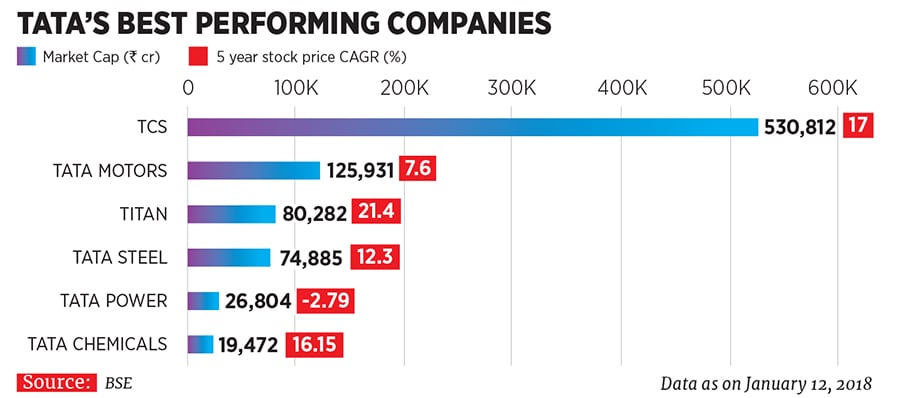

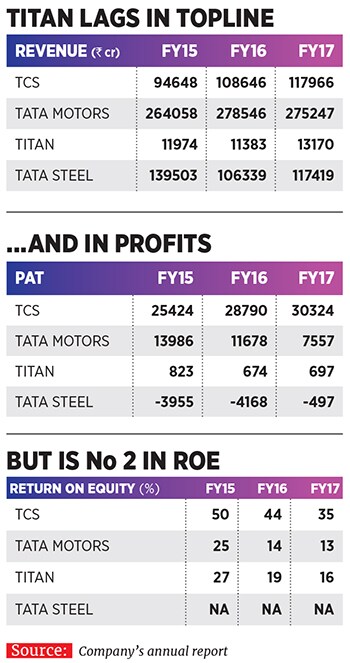

The 63-year-old’s 15-year helm at Titan has been his most fruitful. In November, powered by a 92 percent rise in its stock price in the last year, the company wrested the third slot for the most valuable Tata company from Tata Steel—Tata Consultancy Services or TCS and Tata Motors are first and second, respectively (See ‘Tata’s Best Performing Companies’). It also has the best return on equity in the group after TCS.

Titan’s burgeoning market value also marks an important psychological victory for Bhat, who has come a long way from seeing the company board almost shut down Tanishq in 2002. Through his tenure, Bhat has never let the focus on bottom line slip despite the anaemic margins of its mainstay, Tanishq. At a price to earnings multiple of 90, its stock trades at the highest multiple of all group companies. That’s partly because Titan is a consumer business but, more importantly, the market is discounting a long period of consistent growth—the building blocks of which have been painstakingly put in place by Bhat and his team.Soon after he took over as managing director in 2002, Bhat recalls taking classes with managers where, “I would explain to them what Ebidta was and why it was so important as a driver of market cap. They’d all wonder why this (former) marketing guy was explaining this,” he says. Gone are the days when the board, comprising representatives of Tata Sons and Tidco, were wary of infusing additional capital.

Bhat acknowledges that present cash flows give him all the leeway he needs and some more. Old company hands would like him to be a little more ambitious with that headroom. They point to the fact that the company doesn’t seem to be in the mood to incubate the Tanishqs of the future. “They’ve built a wonderful garden, now all they are doing is tending to it,” says a former employee.

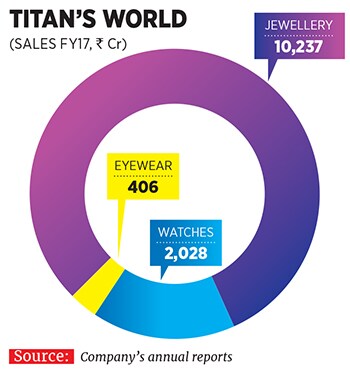

Bhat disagrees. He sees huge growth coming from their present categories even as Titan looks for the next big idea. For now, having shrugged off the demonetisation hit, Bhat has committed to take Tanishq to $2.5 billion (₹16,250 crore) in sales from the present ₹10,237 crore. Bhat also plans to position the company to compound at 14 percent and clock $5 billion in top line in 2025. With those numbers, Titan could have a fighting chance at becoming the No 2 Tata company in market cap.

Segmenting Tanishq

Titan’s biggest achievement in the last decade was the turnaround at Tanishq and it achieving scale from 2010 onwards. With customers latching on to its promise of purity, the business began contributing to a larger share of growth. Still, it couldn’t get away from the fact that gold is a commodity and making charges or designs would only allow the company to charge a small premium. Profit before tax margins at Tanishq are 10 percent. CK Venkataraman, chief executive of the jewellery business, charted a multi-pronged plan to increase margins. Initially, the plan involved increasing its focus on diamond jewellery, which brings in twice the margins of gold. Diamonds now make up 30 percent of sales and Tanishq plans to keep it at this level. “We’ve also been able to push the envelope on gold-making charges so the pressure to do more on the diamond front is less now,” says Venkataraman.

Initially, the plan involved increasing its focus on diamond jewellery, which brings in twice the margins of gold. Diamonds now make up 30 percent of sales and Tanishq plans to keep it at this level. “We’ve also been able to push the envelope on gold-making charges so the pressure to do more on the diamond front is less now,” says Venkataraman.

While diamond sales increased, Venkataraman took a bolder bet with the size of stores. Titan had so far been “the masters of 2,000 sq ft retail”, as one analyst explains. “There is no better company than Titan when it comes to understanding where to place its stores, how much rental to agree to, how to staff its stores and so on.”

In April 2011, Titan got superstar Amitabh Bachchan to launch a massive 25,000 sq ft Tanishq store in the western suburb of Andheri in Mumbai. Such stores were meant to showcase the brand and get consumers to up their spends. Titan declined to reveal the increase per bill values in these stores, but Venkataraman believes that they had a positive impact on showcasing the brand. Customers spent more although on a per sq ft revenue basis, the stores were not as efficient as their smaller counterparts. Titan has since launched large stores across all large metropolitan cities that it is present in. (While launching larger stores, it has also rebranded GoldPlus, a label it had launched for small towns in South India.)

With margins up and a strong brand recall, Tanishq is now working on targeting the wedding market. The inherent advantage here is that bill sizes are much larger, at ₹1.5 lakh as against ₹30,000, which is the average spend at Tanishq. “Titan realised that with smaller bill sizes, it was competing with a host of other discretionary purchases like holidays and iPhones,” says an industry watcher. On the other hand, wedding jewellery also accounts for half of the ₹250,000 crore jewellery market in India.

At ₹1,842 crore or 18 percent of Titan’s jewellery business, weddings constitute a small portion of overall revenue but equity analysts at Ambit Capital estimate wedding jewellery sales grew at 43 percent in the fiscal year ended March 2017. Getting it right in this category could have a disproportionate impact on the bottom line. Tanishq has now launched a sub-brand Rivaah to cater to the wedding market. Ambit estimates that the focus on the wedding market would allow Titan to clock an earnings growth of 33 percent till 2020.  Tanishq has seen a remarkable turnaround Titan even took a bold bet with the size of its stores

Tanishq has seen a remarkable turnaround Titan even took a bold bet with the size of its stores

Image: Courtesy Titan Company

An eye on time

While Tanishq has pulled in the numbers for Titan over the past four years, the company has continued to grow its other two divisions—watches and eyewear. Both present separate sets of challenges. While watches are a better margin business than gold, the company is up against a declining category—watches for both utility and gifting have seen diminishing sales. Titan is working on repositioning part of that business as a wearable device business.

As it pivots the watch business, Titan hasn’t dropped the ball on its bread and butter sales across a network of 8,000 dealers pan-India. In fiscal year 2017, this brought in ₹2,028 crore in revenue with its own brands as well as licenced brands like FCUK, Tommy Hilfiger and Police. The business grew by 9 percent in the second quarter, which is the best performance in the last few quarters. In addition to watches, the Fastrack accessories business has been a bright spot for Titan. The portfolio has been rationalised—helmets are out and women’s bags are in—and stores have been spruced up. The brand has found traction online with a chunk of orders coming from smaller cities. According to Kant, it is the fastest growing brand at Titan with a growth rate of 23 percent in the first quarter of 2017-18.

Titan’s eyewear business is its most promising. It is the highest margin business and has a long growth runway. The company has spent the last decade getting the model right and now has 472 stores across the country. In a sign that the management has confidence that it has figured out the model, nearly a fifth or 95 stores of the 472 were added in the last year.

At the core of Titan’s proposition in this category is the promise to provide error-free prescription glasses in a fragmented market. It is a business that it has experimented with. “For us, it is a question of time and some courage on our part,” says Bhat. Ronnie Talati, chief executive of the eyewear business, sees a significant expansion into small towns as well as a push towards sunglasses, which would increase the addressable opportunity for Titan. Add to that lens manufacturing (lenses regularly sell for upwards of ₹10,000) and it’s not hard to see why eyewear is a high gross margin category.

The Road Ahead

Titan is poised to benefit disproportionately from the Goods and Services Tax, which will bring about a level-playing field between the company and competitors—smaller jewellers, watches brought in through the grey market as well as opticians operating outside the tax net. Titan is also fortunate that except in watches, it plays in categories where ecommerce hasn’t dented sales.

Titan entered the saree business through the Taneira brand and has two pilot stores in Bengaluru

Image: Courtesy Titan Company That doesn’t mean Titan is turning a blind eye to online. In July 2016, it bought a majority stake in online jeweller Caratlane for just under ₹360 crore. “They’ve helped us understand how to work with a limited set of SKUs and push inventory faster while we’ve helped drive store footfalls for them that result in higher value sales,” says Caratlane CEO Mithun Sacheti.

A level-playing field with the informal economy also opens the doors to newer retail businesses that the company can explore. Titan has worked to put in place a Titan Innovation Engine (TIE) that works on solutions that may be incremental—how to staff stores on weekends versus weekdays—as well as transformational—it has worked with IIT Madras to see how drowsiness sets in (the pulse rate drops) and may work on a preventive product for drivers.

Through the same innovation programme last February, Titan took a small step by entering the saree business through the Taneira brand. At ₹25,000 crore, the saree pie is five times the watch market. Here too, Titan would have to go through a learning curve and understand what styles work as well as the layout of retail stores. Bhat says he is happy with the performance of two pilot stores in Bengaluru and plans to open stores in Delhi.

Titan’s earlier franchise was more on a lower ticket size and adornment jewellery, which it is now changing to wedding jewellery. A successful climb up the value chain would mean that Titan has every chance to double its per sq ft sales to ₹200,000. With more throughput and similar capex levels, return on equity can rise substantially in the next five years. This is what happened in Maruti’s case where it moved up the value chain from an entry-level car player to also selling replacement cars.

For now, Bhat has laid out a steady path for the next five years. He’s completed 30 years at Titan and his stewardship has earned him a place on the Tata Sons’ board. Who succeeds him in two years is an open question. He declined to answer saying, “the board will take a decision”. Industry watchers say they would prefer continuity and that makes Venkataraman the obvious choice.

Titan has shrugged off the profitless growth ghost of the past and put systems and processes in place that make it bottom line focussed. “It was my job to focus on the bottom line while the company focuses on creating elevated experiences. The $10 billion (market cap) wasn’t a goal we had,” Bhat says. “It was an outcome of the process we followed.” Focusing on execution should keep the juggernaut rolling.

First Published: Jan 24, 2018, 06:40

Subscribe Now