The digital decorators

A slew of startups offering digitised interior design options has hit the market in the past few years, hoping to bring order, efficiency and predictability to the legacy industry

(Left to right) Co-founders of Hipcouch Pankaj Poddar and Parikshat Hemrajani spotted the interior design services opportunity in 2013

Image: Mexy Xavier

Name me one furniture brand in India,” challenges Pankaj Poddar. Arms folded across his chest, he waits for a response. When an answer is hard to come by—excluding furniture marketplaces like Pepperfry and Urban Ladder—the 40-year-old founder and CEO of Hipcouch, an end-to-end interior decorating services company, smiles knowingly. “That’s because there’s aren’t any [branded players of significance],” he says, “The market is completely fragmented and unorganised.”

The market he refers to is the $20-25 billion—by industry estimates —home improvement market, which includes furniture, décor and renovation services. Some wager that it’s a $30 billion industry. As huge as it is, more than 95 percent of the market is unorganised, serviced by several thousand freelance designers, contractors and labourers.

But therein lies the opportunity. Poddar claims he was the first to spot it back in 2012, along with his co-founder Parikshat Hemrajani. Both engineers by training, they followed conventional career paths in finance and consulting respectively in the US, before returning to India to do “something entrepreneurial”. While hatching plans for a travel startup, it so happened that Hemrajani was doing up his living room. From scouting out a good interior designer to coordinating with the contractors, dealing with opaque prices and erratic timelines, Hemrajani says the experience was a “nightmare”. “We saw the pain points first-hand.” "The industry is rife with unpredictability. We're solving for this." Srikanth Iyer, CEO, Homelane

"The industry is rife with unpredictability. We're solving for this." Srikanth Iyer, CEO, Homelane

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

Promptly, the duo dropped their travel startup plans and started building out a marketplace to connect interior designers with customers. Their venture, Dwll.in, made a match and took a commission without getting involved in execution services. Within three years, Livspace—another end-to-end design solutions company that recently raised $70 million in Series C funding from TPG Growth, Goldman Sachs and existing investors Jungle Ventures, Bessemer and Helion—acquired it. Poddar and Hemrajani briefly worked at Livspace before founding Hipcouch in 2016.

Today, in an industry starved of modernisation, Livspace, Hipcouch and a handful of others like HomeLane and MyGubbi are leveraging technology, marketing smarts and efficient execution to make the customer experience hassle-free. As Srikanth Iyer of HomeLane puts it: “The industry is rife with unpredictability, in terms of pricing, timelines and quality of work. We’re solving for this.”

*****

Young couples mill about at Livspace’s sprawling design studio in Mumbai’s Lower Parel where modular kitchens, makeshift bedrooms and living spaces are on display. A virtual reality (VR) room allows customers to check out their 2D designs for real. They navigate from one room to the next with a joystick vetting their homes before they are built. “Visualising the final look of their spaces hugely improves the overall experience for our customers,” says Anuj Srivastava, who co-founded Livspace with his IIT-Kanpur mate Ramakant Sharma in 2014. Prior to this, Srivastava spent seven years at Google in the Bay area, while Sharma was part of the initial team at fashion portal Myntra.  "Our real competition comes from the unorganised market." Anuj Srivastava, Co-founder Livspace

"Our real competition comes from the unorganised market." Anuj Srivastava, Co-founder Livspace

Image: Madhu Kapparath

According to Srivastava, customers spend about 7-10 percent of their home value on interiors as a rule of thumb. Loose furniture, he estimates, constitutes only 15 percent of that spend, while the lion’s share goes towards services like flooring, false ceilings, electrical work, etc. At Livspace, average customer spends are about ₹10-12 lakh. For the price they pay, customers get a seamless experience—an online survey captures the scope of work, budget as well as customers’ tastes and aspirations. They are then matched with one of the 2,500 “designpreneurs” on Livspace’s marketplace model and an online consultation ensues. A proprietary software renders customers’ mock-ups, and they’re encouraged to visit one of Livspace’s design studios to get a touch-and-feel of what they’re opting in for.

Once the design is finalised customers pay 10 percent of the bill of quantity (BOQ) that the software automatically generates. “We have a catalogue of 3-4 million choices,” says Srivastava, “Think of these as SKUs you would have on an ecommerce platform. As you pick and choose what you want, a shopping cart is generated.” Livspace-approved vendors then provide the products, during which time another 40 percent of the BOQ is paid. Finally, prior to installation—by an in-house team—the balance 50 percent is settled.Livspace pockets 40 percent of the BOQ, while 60 percent goes to the vendors. From its share, the startup pays its designers a 7 percent fee. Gross margins at 40 percent are among the highest in the industry, claims Srivastava, adding that Livspace is profitable at the unit economic level after marketing.

HomeLane, founded by veteran entrepreneur Iyer (he sold his education technology startup Erudite to TutorVista, which in turn was bought by Pearson Publishing) in 2014, works on a similar model with catalogue-based offerings. Customers are profiled using an online questionnaire and matched with one of the 400 designers on their platform. They can then choose to virtually meet the designers on HomeLane’s proprietary ‘SpaceCraft’ platform or meet in person at one of its eight experience centres spread across Bengaluru, Chennai, Mumbai, Hyderabad and NCR. “From the outset we were clear this was not going to be an online-only play. It had to be an omni-channel model,” says Iyer. “Interior designing is not merely a product play. It’s a serviced-product play. Execution and delivery is all important.” With 20 manufacturers on board and an in-house installation team, the Sequoia and Accel Partners-backed HomeLane promises project completion within 45 days of design finalisation or they “pay the rent”. Iyer claims more than 95 percent of HomeLane’s projects have been delivered on time.  "Having in-house designers helps keep a tight control on quality." Ravi Rao, Co-founder, MyGubbi MyGubbi, on the other hand, functions more like a studio with in-house designers. “It helps us keep a tight control on quality,” says Ravi Rao, who co-founded the Bengaluru-based startup along with Umesh Sangurmath and Sunil Rao in 2015. Backed by individual angel investors, including BigBasket co-founder Vipul Parekh, MyGubbi takes on 40-50 projects a month in and around Bengaluru, Pune and Chennai, targeting 30-45-year-olds.

"Having in-house designers helps keep a tight control on quality." Ravi Rao, Co-founder, MyGubbi MyGubbi, on the other hand, functions more like a studio with in-house designers. “It helps us keep a tight control on quality,” says Ravi Rao, who co-founded the Bengaluru-based startup along with Umesh Sangurmath and Sunil Rao in 2015. Backed by individual angel investors, including BigBasket co-founder Vipul Parekh, MyGubbi takes on 40-50 projects a month in and around Bengaluru, Pune and Chennai, targeting 30-45-year-olds.

Hipcouch, backed by angel investors, differs in that it draws on technology only to provide an initial estimate to customers, leading them on to book a free in-person consultation with a designer. “‘How much does it cost?’ is a key question customers want an answer to. Our tech provides that,” says Poddar, adding that in-the-flesh meetings are important to build trust with the customer upfront. He adds that Hipcouch is the only player to provide “truly bespoke” rather than “cheap” catalogue-based solutions. “Interior design is very personal,” he says, “Every customer wants something unique. We can deliver that.”

*****

The opportunity to make interior design services—once reserved for the wealthy—accessible and affordable to India’s increasingly affluent masses is so large that even pure-play furniture players like Pepperfry are jumping in. “It’s a natural extension of our business,” says Ashish Shah, founder and COO of the furniture e-tailer. Its studios, he says, are manned by qualified interior designers, rather than sales people, who help buyers with free, “full-blown consulting” services. “As the largest online furniture seller, we have a captive supply of buyers. So it makes sense to use our studios as points of engagement and get a larger share of wallet from them,” he says, hinting at larger plans in the pipeline. Urban Ladder, another furniture marketplace, also has similar plans. Last year, the startup launched UL Co-lab, a platform that brings together interior designers and provides them with the technology they need to manage customers’ projects from design to installation. It also entered into a partnership with HomeLane for the sale of its furniture to the former’s customers. Asked about the synergies that arise from the businesses, GV Ravishankar of Sequoia, a common investor in both startups, chose not to comment, while HomeLane’s Iyer brushes Urban Ladder off as “just one of our many partners”.Livspace’s Srivastava is also quick to dismiss talk of competition. “They’re all small players [HomeLane, Hipcouch, MyGubbi, etc]. It’s like saying every taxi is competition for Ola… Ola is the only company in its class,” he says. “Our real competition,” he continues, “comes from the hundreds of thousands of contractors who make up the unorganised market.”

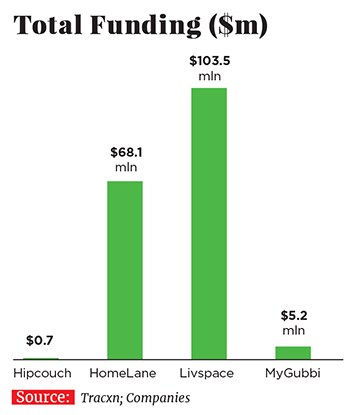

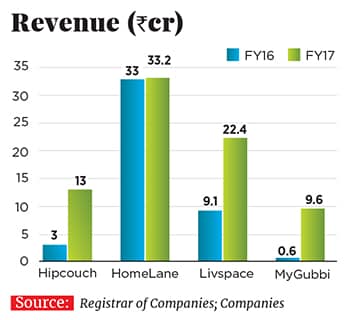

Sure enough, in terms of scale (2,500 designers and 450 contractors catering to over 350 projects per month) Livspace is the largest player, as also in terms of funding. The startup has raised more than $100 million so far, well ahead of HomeLane’s $68 million (See infographic). But in terms of topline, Livspace lags behind HomeLane.

The latter posted revenues of ₹33 crore in FY17, according to the latest available filings with the Registrar of Companies, compared with Livspace’s ₹22 crore. As Prashanth Prakash, partner at Accel India who led the investment in HomeLane, puts it, “It’s not just about the money raised. It’s about scaling in a sustainable manner.” The reason HomeLane has been able to grow revenues rapidly, he says, is because it has been able to relate its brand to its demographic and build trust in the process. “That,” he says, “is HomeLane’s moat.”

On the flip side, Hipcouch takes up around four projects a month with an average ticket size of ₹24 lakh. “We have the highest average ticket sizes in the industry,” says Poddar. While the projects are fewer, he argues Hipcouch is achieving scale of a “different kind”. “Uber can’t launch in a new city in a day’s notice because there are operations associated with it. But WhatsApp can because it’s a tech product. That’s not to say that Uber is not scalable but there are limits to ops-based scale,” he says. “Technology can enable our business, but it’s fundamentally a services business.” So rather than roll out in multiple cities, Poddar is happy to focus on Mumbai, where the market, he says, is huge.

While scale and revenue differ wildly among players, gross margins are uniformly high—anywhere between 30-40 percent. High margins translate into every player claiming to be profitable at the unit economic level. So what then should be the differentiating metric? “I would say net promoter score (NPS) is critical,” says Vishal Gupta, managing director at Bessemer Venture Partners, an early investor in Livspace. Used to ascertain customer satisfaction, an NPS of 50 is generally deemed excellent. Livspace boasts an NPS of 64, HomeLane 56, MyGubbi, which has only recently adopted the metric, 33, while Hipcouch doesn’t measure it. Sequoia’s Ravishankar agrees. “In an execution-oriented business, the final thing is how customers perceive the solution,” he says.

“It’s a market-making moment for us right now,” says Livspace’s Srivastava. The startup has been investing heavily in technology, building its supply chain, growing its designer community and setting up brick-and-mortar experience centres. As a corollary, the startup’s losses increased five-fold to ₹46 crore in FY17, from ₹9 crore in FY16. But “relative losses” in FY18, claims Srivastava, have decreased, without letting in on the figure. “At this stage, the bigger opportunity for us is to invest in responsible growth and create the market,” he says.

As the slew of players follow suit, the biggest challenge, they say, is building quality supply. While the design component of their offerings is well in place, the actual manufacturing often proves problematic. Those who can cut through the chaos, organise the back end and create a simpler, happier and more predictable experience for the customer—repeatedly—will emerge winners.

First Published: Oct 30, 2018, 11:41

Subscribe Now