The Bootstrapped Buddhist: How Sridhar Vembu built Zoho

Fuelled by Sridhar Vembu's vision, and without any external funds, Zoho Corporation is helping shape the future of work

It is a good time to be Paramasivam Saran Babu, a 28-year-old product manager at Chennai-based Zoho Corporation Private Limited. He drives a car he likes—a Maruti Suzuki Swift (diesel), which he has modified to look similar to a Mini Cooper. Last year, he got married and was able to take his wife to his own house. It was an arranged marriage which only took place because the bride-to-be had convinced her parents of her potential husband’s career prospects. Babu, happily, is living up to her expectations, traversing the world from the Bay of Bengal to the Bay Area with opportunities to build software that shapes the future of how we work.

Back in 2005, Babu could not have envisioned this life for himself. Then, he was trying to finish his class 12 at a local government-run “corporation school”, and get a job. His father was in a tough spot, fighting diabetes and working long hours operating a printing press machine his family needed additional income.

It was around the time that at Zoho, then still in its AdventNet Inc avatar, Sridhar Vembu and his co-founders, which included his brothers, were about to put into action a radical plan: Hire talented young adults from low-income households, like Babu, straight out of class 12, and train them to build software products in India for the world.

“I hardly spoke any English at the time, but I was really good at math… maybe that’s why they hired me,” says Babu, who was one of six young people recruited into what would become the first batch of trainees at Zoho University, the company’s internal training programme that has seeded talented youngsters across teams. Today, nearly 15 percent of the company’s 3,600-strong staff comprises graduates of this programme. As for Babu, he has become the product manager for Zoho Creator, an important software product that is part of a suite of internet-based applications sold by Zoho Corp. He has a team of 30 and another 60 collaborate with him on the product. Zoho Creator is used by businesses to build applications on-the-go, and deploy them rapidly. Its users span from Chennai to California: From SRM University next door to the Zoho campus, about an hour’s drive south of Chennai city, to the Napa Valley Film Festival.

Professor B Rajendran, Babu’s trainer, is particularly proud of his young student’s achievements: “You know, once he went to Japan to help a customer with using Zoho Creator,” he recalls. “He was so good that they wanted to offer him a job, but Babu would have none of it.”

“I owe it all to Sridhar,” is Babu’s pithy explanation. “He even convinced me to put aside my concern that I didn’t have a college degree, and get married,” he says. “My wife is an MBA,” he then offers, not without a trace of pride.

Babu’s journey is validation of Vembu’s vision, one that has evolved over two decades and led to the creation of a leading global SaaS (software as a service) corporation.

If you were to bump into Sridhar Vembu, nothing about this diminutive figure, typically in a black polo-neck T-shirt, denim pants and dark-tan leather sandals and slightly dishevelled hair, will suggest he runs a global company and owns it too. The T-shirt is likely to have the Zoho logo embossed on it—spelt out in four square blocks that look like they’ve come from a children’s alphabet building set.

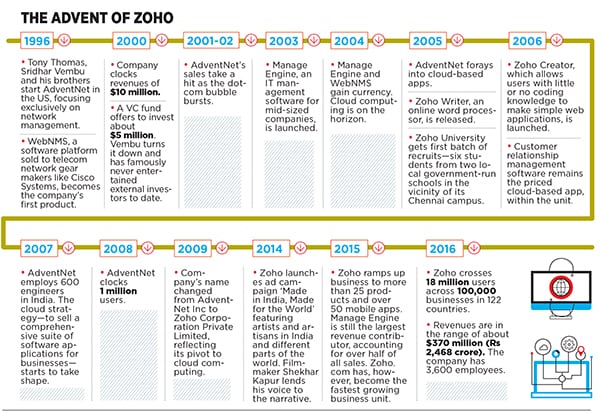

But nothing else at Zoho Corp is child’s play: The 48-year-old Vembu is deadly serious about how he runs the company, which he co-founded as AdventNet Inc in 1996 with his brothers Kumar and Sekar, as well as Tony Thomas, an entrepreneur who wrote an early version of the software that would become WebNMS, the company’s first product which found buyers in telecom network equipment makers like Cisco Systems, Inc. (Thomas was three years senior to Vembu at the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras.)

Thomas served as the first CEO of AdventNet and was also its chairman and chief technology officer for a spell. Vembu was its chief evangelist, which meant he focussed on promoting and marketing the technology the company was selling. Vembu took over as CEO in 2000 while Thomas, in 2004, moved out to start another company Applibase Inc in Sunnyvale, California, which was acquired by internet company Vtiger. He now runs Edcite, an education startup in the Bay Area, which he founded four years ago. Thomas retains a stake in Zoho, and also serves as a member of the advisory board at Vembu Technologies Private Limited, founded by Sekar.

AdventNet became Zoho Corporation Pvt Ltd only in 2009, and it was around that time that the direction in which the company was headed crystallised. Businesses were increasingly turning to the internet for rented software to run their operations, rather than buy licences for expensive software. Zoho.com, the company’s youngest division, offering internet-based software for work—from email to collaboration and office productivity tools to software for managing customers, vendors and partners—was emerging as the most promising for the future.

There was also a shift in geography: While AdventNet Inc was a US company with an India development centre, Zoho Corp is incorporated in India and the company’s Pleasanton, California, centre remains the global headquarters. Vembu, who works out of the Pleasanton office which is sales-facing, visits India, where all of the development activity takes place, usually once every quarter.

Apart from Zoho.com, Zoho Corp has two other divisions: The telecom network software division WebNMS, which the company began with, and the Manage Engine division, started around 2003, which builds software for companies to monitor and manage their own IT networks. Manage Engine accounts for over half of Zoho Corp’s revenues, but Zoho.com is the fastest growing. Vembu won’t reveal any additional details of the privately held company, but in November 2012, Bloomberg published an interview with the Zoho chief that put Manage Engine’s revenue at $120 million, while Zoho Corp’s overall revenue was close to $200 million at that time. Vembu likes to say Zoho Corp today has revenue per employee that’s twice that of Infosys, which at a rough reckoning puts his current revenues at about $360-$370 million.

More importantly, the 20-year-old company has been profitable almost from the word go. The word ‘profit’ has a magnetic draw for venture capital (VC) firms and, should Vembu have chosen, it would make Zoho Corp a genuine unicorn a couple of times over. But he will have none of it. Even as chief evangelist at AdventNet, Vembu always highlighted how the company had built its product successes with zero external funding, having started with the co-founders’ savings and some help from close family and friends. That Vembu’s wife Pramila Srinivasan, also an engineer, was working, helped. Further, Thomas had taken a payout at AT&T Bell Labs and the money helped bootstrap the company, Vembu had told Silicon Valley entrepreneur Sramana Mitra—famous for her One Million by One Million incubator/accelerator project—in an interview, which she published on her blog in July 2007.

“Why sacrifice freedom? That is the primary reason [for not taking external funding],” Vembu tells Forbes India during an interview at the company’s office in Chennai’s Estancia IT Park in April. “We’ve done a lot here at Zoho and we operate on our own clock—it’s an internal conviction,” he says. “If you take money, you have to necessarily make some compromises.” The only dalliance with a VC some 15 years ago taught Vembu to never revisit this option. “I saw this clause in the agreement that within seven or eight years, we have to guarantee an exit or liquidity for the investor. When I asked them about it, they said it’s a pretty standard clause,” he says. “[But] there was no way I could guarantee that.”

Not having to answer to outside investors also gives Vembu the freedom to experiment with options like Zoho University. Or invest in long-gestation projects. Zoho.com was once such a project, making little money for a fairly long time, but increasingly becoming the future of the company. “We call ourselves the operating system for business. When you think of an operating system, you think of something that runs your device. Zoho has software that runs your business. That is our vision, and we are hugely ambitious in this,” Vembu had told reporters in April.

The Zoho.com portfolio comprises 30 apps today and is growing rapidly. “It is the broadest and the deepest cloud suite,” Vembu said in that press conference. “No one else, not Microsoft, not Google, offers anything like the breadth and depth that Zoho has now. We have customers who have 80 percent of their business running on Zoho, and we’re working on the remaining 20 percent. And we have over 100,000 customers [a milestone Zoho reached recently].” Those customers translate to 18 million users in 122 countries. “The broader vision is that Zoho is the operating system for work. Anyone who has any work to do, we want them to come to Zoho,” he said. “As proof, we offer ourselves. Everything at Zoho Corp runs on this software, including this presentation,” he pointed out at the press conference. Reporters could log into Zoho and follow a link that opened each slide of the presentation on their laptops or smartphones, and they could type out questions within the app, which would immediately appear on the presenter’s smartphone.

“Zoho has cracked two things. One is, how do you build scalable global products from India, and specifically from Chennai. They have shown the world that they can create a global product that competes with Salesforce.com or Google’s cloud, sitting out of Chennai,” Tarun Davda, a managing director at early stage VC firm Matrix Partners, told Forbes India in a phone interview from Mumbai. “Second, which is equally important, is how do you serve, and sell to, US customers sitting in India with very minimal resources. Zoho knows how to do this at scale,” he says.

What Zoho is attempting is to either build every type of software a company will need to run its business—from email to customer relationship management—or give customers the ability to build their own app, for instance through products like Zoho Creator.

This impacts how people work in real ways. “Clearly technology is affecting how organisations are structured. The traditional hierarchy of top-down structures is giving way to more fluid networks—doesn’t matter what title you have,” Vembu tells Forbes India. Also there are companies, of which Zoho is a strong example, that are “increasingly driven by contextual knowledge”.

“Formal education only takes you so far, but most of the contextual knowledge comes from actually doing something,” he points out. The internet is a force multiplier and now, if one wants to learn something from scratch, it takes perseverance, but the tools and the lessons are available almost for free. “It’s very powerful. It is changing the way education works, companies and organisations work,” Vembu says. “That’s why Zoho University is about this contextual knowledge. We impart that kind of thinking to the trainees so that they can themselves go on to acquire what they need.”

The ability to make a context-based difference has also become the hallmark of companies started by those who earned their spurs at Zoho. In fact, the number of former Zoho staffers who have now become their own bosses speaks to the relevance of Vembu’s approach.

Take the case of Girish Mathrubootham, who joined Zoho as a pre-sales engineer in 2001 and rose to become vice president of product management by 2010, heading the Manage Engine division at this point, he quit to start Freshdesk. The startup, as the name suggests, is bringing a fresh approach to helpdesks, where context matters: For example, Freshdesk’s technology makes it possible to chat with customer support from within Zomato’s food-ordering app.

Three other former Zoho staffers, Arvind Parthiban, Santhosh Kumar and Naveen Venkat, have just raised $1.5 million in seed funding from Accel Partners and Matrix Partners for their website testing startup Zarget. Mathrubootham has invested in his personal capacity in the Chennai-based venture.

Their Zoho pedigree was an important factor in getting them Matrix Partners’ backing, Davda says. “Zoho is a great training ground… the training they got on what the sales model should be, how do you serve US customers, what kind of products do such customers value… all of these things are some fantastic learnings,” he says. Zarget’s website optimisation software is innovative, and the young startup has seen some early successes with customer wins, but “if you ask me, at this stage, it’s really the team that we are backing, that’s given us a lot of comfort,” Davda says.

Then there is Navaneeth Krishnan, who calls himself a “garage-stage employee” at Zoho, having worked there when it had a staff strength of about 100 people. He was the development lead engineer for OpManager, a network monitoring software product, and reported to Mathrubootham. Krishnan now is co-founder of Bengaluru’s Voonik.com, an online fashion retailer for women.

Parthiban recalls a bunch of Zoho engineers, including him, hanging out together they referred to themselves as the “Zoho mafia”. All of them have started their own ventures now and some of them, including Parthiban, are actively trying to make Chennai a strong base for startups, focussed on internet-based software products.

“The answer is very, very clear in my mind—it was the operational freedom,” Mathrubootham says during an interview at his Chennai office. “Zoho as a company is very open to experimentation, and people like me, who had no background in product management, were given opportunities to do such work, to make mistakes and learn. There was freedom to do what you thought was right.”

Babu, the product manager for Zoho Creator, also points to the respect given to novices like him. “People here never treated me as a kid. When I started working, I was just 17, and my team leader was more than 10 years older than me,” he recalls. “Whoever has the talent to transform a product, they are moved forward.”

This culture permeates from the top. “When Sridhar first came to visit us [at Zoho University], I didn’t really understand what it meant to be a CEO. We added him to our chat group and we used to chat regularly, which we do even now. That day, after he left the class, our trainer told us that he was also the owner of the company.”For Vembu, the context for building Zoho and its unique culture is India itself. He was born in the village of Umayalpuram, famous for Carnatic classical mridangam artist Umayalpuram K Sivaraman, who is also a cousin of Vembu’s mother. Vembu’s father’s village, Chidambaranathapuram, is around 30 km down the Kaveri, not far from the Kollidam branch of the river. “I spent a lot of my childhood there, so it kind of shaped my world view. There was no internet, remember, so the newspaper was my window to the world,” he says. Vembu credits senior journalist Arun Shourie, in particular, for influencing his thinking. “I used to devour his writing. I was born in 1968, and in my formative years, I read The Indian Express and was shaped by his fearlessness.”

One particular experience left a deep impression on a young Vembu. “An old lady in my father’s village— this was probably when I was 12 or 13—told me, you are a smart kid, you’re going to do well in life, but however well you do, don’t ever forget that you come from this village as the village can’t afford to lose you,” he recalls. “That kind of stayed with me. In India, to me, it was almost like an existential question: Why are we so poor, and when you have travelled abroad, the contrast is even more stark. Then I [tried to] reason what would it take [to improve the situation]. People say government, but government can’t create jobs it has to be in the private sector. We have to create a lot more companies, so we thought we will jump in and do something.”

It is also why Zoho isn’t for sale, says Vembu. “Because there is a mission and it won’t be sold like just another company.”

His brother, Kumar, who is a year younger than him, remembers a conversation from around the time when Vembu and he were in the US, shooting the breeze one day, asking why no one’s doing anything about India’s problems. Kumar remembers asking something like, “You know, we’re all, like, in the top 0.1 percentile of educated people… if we won’t do it, who will?”

Vembu had topped class 12 exams and got into IIT-Madras, after ranking 27th in the challenging Joint Entrance Exam thereafter, he went to Princeton University for a PhD in electrical engineering. Kumar went to a local engineering college, but developed a fierce work ethic through stints at the TeNet Group at IIT-Madras, built by Professor Ashok Jhunjhunwala, and at HCL-Hewlett Packard, which had an R&D unit in Chennai at the time.

Both brothers ended up working in Qualcomm.

“We all came out [of our jobs] at the same time,” Kumar says, including Tony Thomas, who was working for AT&T Bell Labs. Two others, Shailesh Kumar and Srinivasa Kanumuri, as vice presidents of engineering and product services respectively, played an important role in shaping the early growth of AdventNet. There was no great plan, but a bunch of talented young people hell-bent on surviving by building something of their own, Kumar says.

Kumar returned to India in 1997, and was president and COO of the company for over six years, while Vembu stayed on in the US to find customers and do what he loved best—evangelise technology.

Kumar now runs GoFrugal, a software maker for retailers, specifically in India. Sekar continues to run Vembu Technologies, which even sold one product line SwisSQL to AdventNet in December 2003. Radha Vembu, their sister, runs Zoho Mail and Manikandan Vembu, the youngest of the five siblings, is chief operating officer of Zoho.

“Sridhar was the superstar in our family,” Radha says in a phone interview. Their father worked in the Madras High Court, and retired as the head of the private-assistants’ section but it was Vembu who played a father-figure’s role in her life even though the age difference was not much, adds Radha, who is three years younger to him. “He didn’t help us academically, but pushed us to aim for the next milestone.”

He applied the same rule to himself: “As a kid, he wouldn’t talk that much. He was a very quiet and studious person, but from a very young age, he had this thing that whatever he did, he had to do it really well,” says Kumar.

He also had to do it differently.

As a young man, he was never afraid to break rules, Radha points out. While their parents were from a conservative, traditional middle-class family, “Sridhar was always bold enough to express his own views frankly, but he also managed to not hurt them.”

In his third or fourth year at IIT, after a particularly involved argument with his father about some religious rituals, “he went back to the IIT hostel and wrote a letter saying, ‘Let’s agree to disagree and not allow it to come in the way of the (father-son) relationship’.” He hates rituals, but he won’t interfere with others’ beliefs, she points out. “He says he is a Buddhist,” she says. He follows and preaches the middle path—from his personal life to official interactions. “He is never extremely happy or extremely sad.”

For instance, Zoho Mail is very important to the company, and at times, after a mistake, even if Radha or her colleagues would be upset, Vembu’s attitude would be, “learn from it and move on”.

Some of this is drawn from painful personal dimensions of his life: “I have one kid with autism,” he says. It is an important reason for continuing to live in the US, where quality care is more easily at hand. “Only one son, he’s 17 now, it’s a personal and a hard challenge.” He credits his wife, Pramila Srinivasan, for bearing the brunt of the toughest aspects of caring for their son.

This challenge has also influenced her work. Srinivasan is founder and CEO of Palo Alto-based MedicalMine Inc, which makes electronic health records and clinic management software. She collaborated with NetSuite to build Children’s Autism Recovery Map or ChARM, a web application to track the care of children suffering from autism and other chronic diseases, eWeek reported in October 2010.

It is a challenge, being the parent of a child with autism, Vembu admits: “But it makes you more patient, less frustrated, and it also makes you appreciate that not everything in life will go perfect. Life is going to have sometimes unsolvable challenges, and you just have to keep marching.”

And Vembu feels he must be even more vigilant to this credo today. “Ten years ago, it was impossible to raise $1 million in Bengaluru. Today you can raise $100 million or a billion. It’s not natural, it’s not real. That distorts behaviour all around.”

The one time Vembu was given a term sheet by a VC, 15 years ago, he was looking for about $5 million, “which sounds ridiculous today… and we were actually making $10 million in revenue at that time. Today you can have $1 million revenue or zero revenue and you’re offered $100 million. It’s not real. It will end, I can guarantee it will end, nobody can predict when, but it won’t be pretty when it does.”That said, he sees India coming into its own not just as a production base, but also as a market. And Zoho itself has partnered with national distributors such as Ingram Micro for some of its on-premises products.

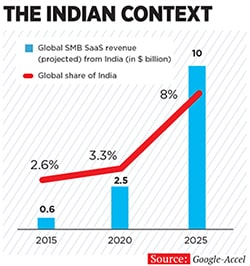

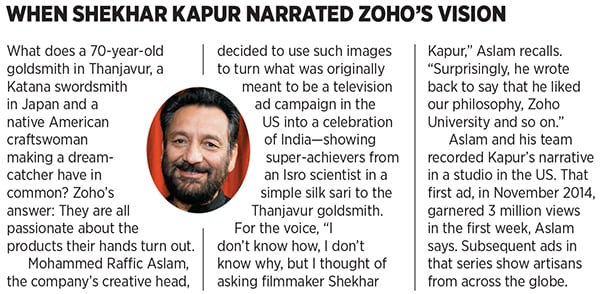

In the years to come, Vembu wants to see Zoho as a “global leader in technology and in what we call the operating system for work.” Indian companies selling internet-based software for business applications can capture as much as $10 billion of the worldwide demand for such products by 2025, Google and VC firm Accel Partners estimated in a report released in March this year. The demand itself is projected at $132 billion, from about $60 billion today, when the Indian companies sell about $600 million worth of internet-based software.

This is why Vembu feels Zoho’s numbers, “compared to the global size of the market we are in,” are small. “We could have a billion users we are closer to 20 million today. We could have more organisations using Zoho,” he says. More people should be using Zoho for their personal and individual work, and the company should extract more business use as well. “The 20 percent of work where people aren’t using Zoho will still take 80 percent of our time,” he says. The effort to get people to switch to Zoho, by making it an attractive option, “is our ongoing mission”.

This upward and onward approach manifests in Zoho’s people too. Take the case of Babu. One of his next projects is to upgrade from his faux Mini Cooper to an Audi. “It will happen,” he says confidently, “maybe in a year or two.”

First Published: Jun 06, 2016, 07:44

Subscribe Now