The Big Future Group Sale

Will India�s retail king sell everything he�s built?

IT’s not about what’s the right thing to do. It’s about what’s the first thing you can do.”

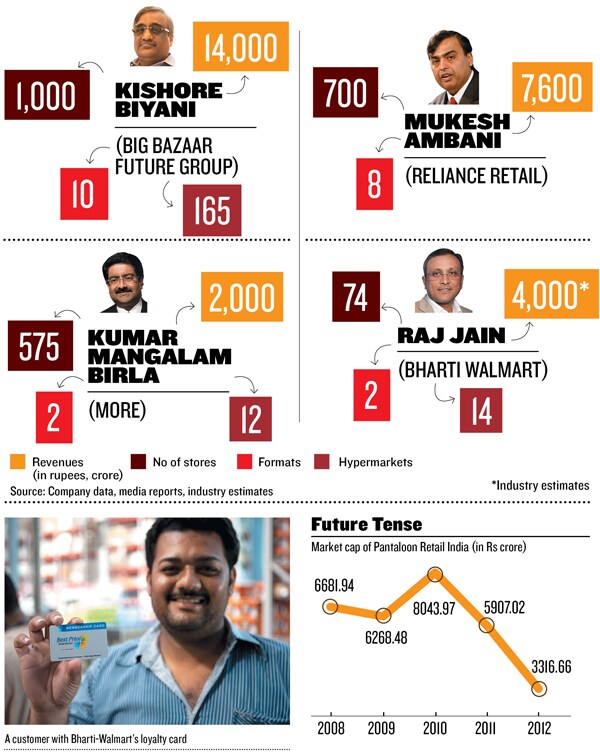

Nobody had looked Kishore Biyani in the eye before and told him that. But Sameer Sain, the founder of Everstone Capital, had to do it. His words made Biyani squirm. It’s not the kind of thing you tell a man who’s demonstrated to the world you can build an empire worth $2.5 billion (Rs 13,800 crore) in 15 years. But that said, his debts were in the region of a back breaking Rs 9,000 crore, roughly $1.66 billion at today’s exchange rates.

Biyani knew it was the kind of number which could swamp all the Future Group companies he had meticulously built over the years to earn himself the title of “India’s Retail King”. To rid himself of the burden, he was negotiating with prospective lenders and suitors of all kinds. But Biyani’s problem was this: How do you make a considered decision when you’re running out of time? More importantly, how do you know what is the right thing and what can possibly go awry?

Biyani and Sain had known each other for a long time. When Biyani was starting out, Sain’s father was one of his most trusted partners. That is how, when he was just 18, Sain got to intern at Pantaloon, one of Biyani’s earliest ventures. He recalls those times in the mid-90s when Biyani placed him at his trouser manufacturing facility in a run-down part of Andheri, a Mumbai suburb, to iron trousers with three pleats. Sain was pretty damn sure the trousers would bomb. Another matter altogether that the trousers went on to become a rage and he got a glimpse of Biyani’s genius. The man knew what the market wanted.

And then, in 1997, Pantaloon made its retail debut with a store in Kolkata that catered to men. It was the start of Biyani’s incredible run. On Sain’s part, soon after his internship was done, he went off to the US to pursue a degree in finance and ended up at Goldman Sachs. But he stayed in touch with Biyani and they bounced ideas off each other regularly.

In 2007, when Biyani thought up of creating a financial services firm that could piggyback on his fast-growing retail empire, he asked Sain to come back and set up Future Capital Holdings (FCH). Three years later, after an acrimonious parting, Sain took the investment banking and private equity portfolios of FCH to set up Everstone Capital.

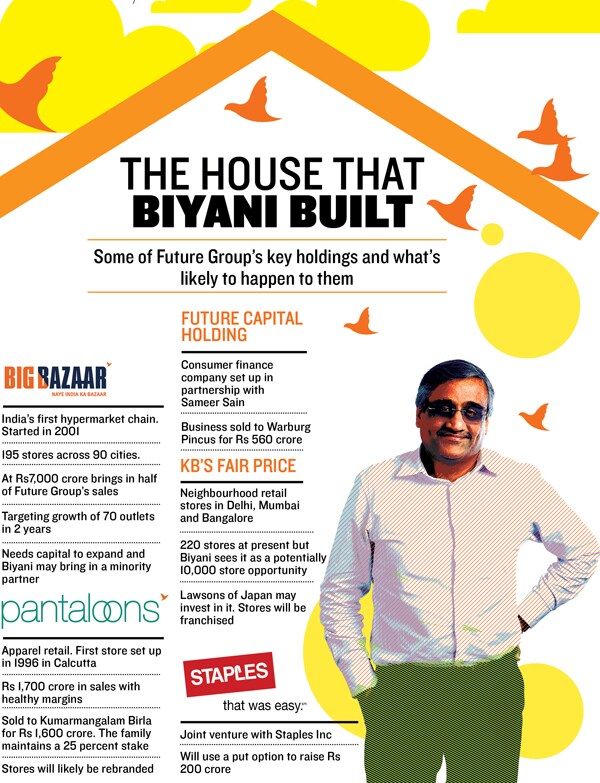

But it didn’t stop Biyani from calling up Sain for advice. “When you have people out to kill you, you don’t wait to think what the best move to strike back probably is,” Sain told him.On April 30, this year, four weeks after his chat with Sain, Biyani made a move no one expected of him. He agreed to hand over majority control of Pantaloon, his department store chain to Kumar Mangalam Birla, chairman of the Aditya Birla group. It helped that Birla was a fellow Marwari. Biyani retained a 25 percent stake for himself. And then three weeks later, Biyani sold his majority stake in FCH to Warburg Pincus, the blue-blooded private equity firm.

These two transactions—along with a few others in the pipeline—ought to help Biyani halve his debt and move to a safer harbour.

What nobody is clear about though is the endgame. With debt out of the way, will the maverick think up something dramatic as he had 15 years ago? Or will he simply ride away into the sunset by selling his stakes to a global retailer at a fancy valuation? The latter has been the subject of intense speculation since 2001 when he thought up Big Bazaar—the Indian version (or a Biyani-version, if you will) of a hypermarket.

What we know is this: The endgame will be around what he does with Big Bazaar. It contributes to half of the group’s turnover and is his crown jewel. But after taking in Sain’s advice and doing the unthinkable by giving up stakes in Pantaloon and FCH, he’s earned some breathing space. Trying to second guess him though is a bit like watching S Sreesanth run in to bowl. Nobody has a clue where he’ll pitch the next ball.

Beginning of the end

How does an entrepreneur obsessed with growth live in a world where interest rates are on the rise, the economy’s slowing down and the balance sheet is stretched? The most obvious thing to do is curb the appetite to grow. But that’s awfully difficult he admits. “It is like a snake shedding skin,” says Biyani.

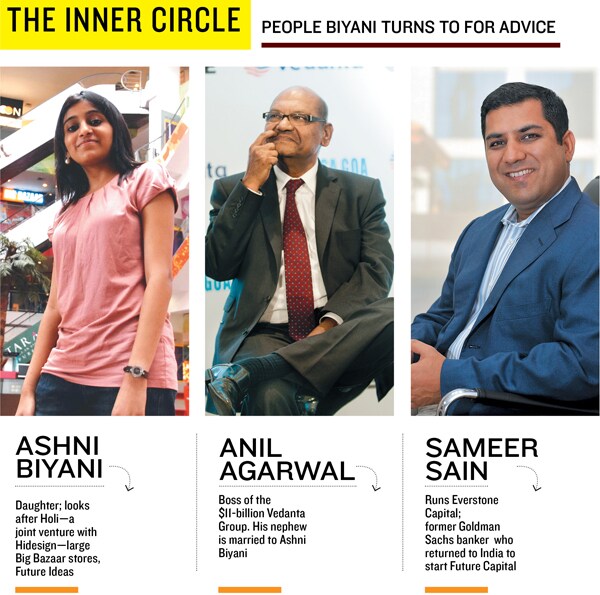

Two people helped him take the call. The first was Ashni, his elder daughter, whose judgement he trusts. The second was Anil Agarwal, chairman of Vedanta. Agarwal’s nephew Viraj Didwania married Ashni a couple of years ago. Biyani says he learnt from Agarwal’s sense of detachment. “But it is never easy to question all that you’ve done, and turn out a new leaf overnight,” Biyani explains.

After much brainstorming with them, Biyani decided to put everything on the table. This March, he called in all of his key lieutenants and announced a war on debt. “It was pretty clear we had to put all the rods in the fire and depending on the outcomes, we’d figure out how to move forward,” says Damodar Mall, director of food strategy at Future Group. Biyani was to lead the charge aided by his cousin Rakesh Biyani, Mall and Anshuman Singh, CEO of Future Logistics.

The plan to sell FCH was set in motion sometime last June. V Vaidyanathan, or Vaidi as the CEO of FCH is popular known as, got to know of that on television when Biyani described FCH as a “non core asset”. He was just in his 10th month at the company and had joined after being relentlessly wooed by Biyani to walk out of his job at ICICI Prudential. Vaidi bit the bait when he was offered a 10 percent stake in the venture and the challenge of creating a new retail franchise from scratch.

All Vaidi could do was shrug his shoulders, gather his wits and start looking for a new strategic investor in place of Future Group. The mandate was given to Morgan Stanley. But the problem was, FCH didn’t have a business model. Vaidi had just about managed to rebuild the top team. Private equity firms like Baring and Bain Capital considered the proposition as did the South-based Deccan Chronicle group. But fact was, the Pantaloon stock was underperforming the market, its book was full of debt and Biyani was in a tearing hurry to get FCH out of his way.

Luckily for Vaidi, while on a flight to Mumbai, he got talking to his co-passenger. He turned out to be Narendra Ostawal, a principal at Warburg Pincus. Three months later, Warburg Pincus decided to buy into FCH. The deal reduced Biyani’s debt by Rs 500 crore ($90 million).

Even as all this was happening, Biyani reached out to Vishal Kampani of investment bank JM Financial six months ago. He wanted to leverage Kampani’s relationship with Kumar Birla to hammer a supply chain relationship with the latter’s Madura Garments. Biyani argued the two businesses could benefit a lot if Madura’s strengths in men’s wear could be combined with Pantaloon’s strong line-up in women’s wear.

“When I started to get to know the two businesses better, I could see he [Biyani] would have to sell something big,” says Kampani. As things turned out, Birla’s strategy team, led by Dev Bhattacharya, had figured as well that if Biyani had to get out of the hole he was in, he’d have to let go of something large.

So, late in March this year, Kampani told Biyani, the Birla’s would be interested, but only if they could acquire a controlling stake in Pantaloon. Biyani was taken aback. It took Kampani three one-on-one meetings with Biyani to persuade him to even consider the deal. Eventually, Kumar Birla had to step in. After three rounds of closed door meetings and persuasion on part of Kampani to up the Birla offer, a deal was struck. It helped Biyani offload Rs 1,600 crore ($288 million) of debt and retain a 25 percent stake in the demerged entity.

What eventually caught Biyani’s eyes were the numbers. “In two years, the value of the 25 percent in the demerged entity will perhaps be worth much more than when it was part of the holding company Pantaloon Retail India Ltd (PRIL),” says Biyani. By combining the two retail chains, Kampani says he expects a margin boost of at least 2-3 percent from rentals alone.

This month, Biyani says he is likely to exercise a put option in his joint venture with Staples that will bring him Rs 200 crore. He plans to also exit his insurance joint venture with Italy’s Generalii. And it could be tough for Biyani to get a buyer to cough up the Rs 1,000 crore ($180 million) that he expects from his stake sale. If all of these go to plan, Biyani would have halved his debt across the group to Rs 3,800 crore ($684 million).

The single-minded determination with which Biyani has pursued the war on debt has caught many by surprise. Yet those who know him for long say that he revels in such tough situations and it usually brings out the underdog in him. “Kishore has a remarkable quality of passionately pursuing an idea—and when that doesn’t work, he knows how to walk away from it,” says Madhav Bhatkuly, who was among the first investors to spot Biyani’s entrepreneurial flair in 2003 before selling out at a significant multiple in 2007.

His entrepreneurial flair and instinct helped Biyani experiment with different retail formats and junk them as easily whenever it didn’t work. But the model works only when there’s liquidity in the markets and raising capital is easy—not in the kind of world we live in now.

The real ace up his sleeve

The optimist in Biyani is hoping the capital markets will pick up once again and allow him to raise money on the back of a cleaner balance sheet.

Privately though, Biyani has confided in at least two institutional investors that he’s prepared to “sell everything,” provided he gets “full value”. While his debt may have gone down, he knows there isn’t much he can do without additional capital. That is why he’s hoping the government will allow foreign direct investment (FDI) in multi-brand retail.

Insiders say he’s made several trips to Bentonville, headquarters to the American retail giant Walmart, where he’s met the top brass to discuss options. At his peak, sources say Biyani was offered a term sheet from an undisclosed buyer that valued Big Bazaar at Rs 12,000 crore ($2,160 million). Chump change for Walmart!

Image: Biyani, Birla: Vikas Khot Ambani: Reuters Jain: Amit Verma

But it is unlikely his Indian competitors, Reliance or Bharti-Walmart, will pay that kind of money to acquire the 165 hypermarkets he now has. Given market realities, it is unreasonable to expect any Indian group to pay more than Rs 7,000 crore ($1,260 million) for these assets argues Kampani of JM Financial. Simple back-of-the-envelope calculations indicate it is cheaper for them to pursue organic growth. Malls have fewer takers, rents are moving south and with downsizing across the retail business, the cost of acquiring talent is cheaper as well.

Another possibility being spoken of is that if FDI is allowed, it is entirely possible Kishore Biyani, Sunil Mittal and Walmart will come together to form a three-way alliance. It sounds plausible because Biyani and Mittal share a good rapport and Mittal on his part in already in a relationship with Walmart.

The hitch here though is that of late, Walmart is increasingly wary of the integration challenges that come with buying out local retailers in emerging markets. For instance, it struggled to merge its $1 billion buyout of Trust Mart, a Taiwanese chain of super stores in China. After investing tens of millions of dollars in renovating Trust-Mart’s three outlets in Shenzhen and Guangzhou, to Walmart’s disappointment, performance declined 30 percent. Several Trust-Mart executives quit as well during the three-year merger period and Walmart was compelled to announce a temporary suspension of the merger process.

Much the same challenges could come up with Big Bazaar. It is still to achieve cash break-even, has many unprofitable stores, lacks standardised systems and processes to track inventory and reduce wastage. It also places too much reliance on the entrepreneurial ability of each store manager. And unlike Best Price Wholesale, the cash-and-carry format launched by the Bharti-Walmart alliance, or its Easyday hypermarkets, almost every Big Bazaar store is unique, depending on size and location.

The other problem is the differences between Walmart’s philosophy and that of Biyani. The American retailer believes in a template across the world and its stores are built to precise specifications. Biyani, on the other hand, believes Indians love the chaos of traditional Indian bazaars and his stores reflect that. If these cultural differences can be ironed out and the government approves FDI, buying Big Bazaar could help Walmart consolidate in one of the most attractive markets and help it block rivals like Carrefour and Tesco from gaining a toehold in the country. And of course, provide Biyani with an exit option. If this doesn’t fructify, expect Biyani to put a plan in place to at least double the numbers of stores he has over the next four years.

But staying ahead will get increasingly difficult. As newer entrants like Reliance, More and Star India Bazaar expand their footprint, it will begin to put pressure on Big Bazaar’s volumes. Biyani is aware that unless he fixes his business model and makes the chain profitable on a standalone basis, valuations will tend to be depressed. That explains why he is now focussing on more profitable businesses like fashion wear instead of general merchandise.

Rakesh Biyani has been given the mandate to fix operations. Often described as ‘smart, sharp, hard working and numbers driven’, Rakesh was instrumental in setting up the back-end at the Future Group. But he receded into the background into 2010 when the stores took off in a big way and getting the back-end right was no longer priority.

Rakesh’s return is an indicator Kishore Biyani is convinced having professional managers run operations is a bad idea. This, once again, is a far cry from December 2010 when Kishore Biyani created a Family Council. The idea was to pull the family out of running operations and focus instead on governance and strategy.

“It isn’t inconceivable for Biyani to unlock full value—upwards of $5-6 billion—from Big Bazaar in 4-5 years,” says Kampani. If Biyani can last until then, there’s a pot of gold to be taken home. Question is, where does he find the capital to scale up?

The Japanese Red Herring

Some clues could lie in a chance meeting Future Group’s head of food Damodar Mall had on the sidelines of the India Retail Forum in Mumbai last July. A senior executive from Mitsubishi Corp walked up to Mall shortly after he had finished a presentation. The executive wanted to understand Mall’s perspective on the future of neighbourhood stores in India.

Until then, even an experienced retailer like Mall knew very little about Mitsubishi’s interests in food and retail. He soon discovered it ran a $70 billion (Rs 3,88,000 crore) business group—Living Essentials—with interests in food and retail, among other things. It owned 32 percent of Lawson Inc, a well-known Japanese convenience store chain, with more than 8,600 stores across Japan, generating a top-line of 1.5 trillion yen ($19 billion).

As the meetings progressed, the inscrutable Japanese gave little away about their line of thinking. Mall then decided to bring Kishore Biyani in. That turned out to be a masterstroke. In Japan, founders are held in high esteem. That is because over the last two decades, most of the Japan’s largest corporations are run by professionals. Their original founders are either died or passed the baton on. Their economy too is practically at a standstill. The current generation of managers therefore have few role models to look up to. So, when Biyani walked in, the Japanese took it as an honour and indicator of strong strategic intent to close a deal.

Almost on cue, the negotiations picked up pace with Keniichi Nakagaki, the chairman of Mitsubishi India, joining the fray. If the deal comes through, it could work at two levels. Either Lawson’s could end up running a local franchised version of KB’s Fair Price chain of convenience stores across the country. Or Mitsubishi could join hands to build the backend for a large food sourcing operation. Between these two transactions put together, the Japanese conglomerate could put in upwards of $300 million in investments into the Future Group.

Lawyers from both sides have struggled to work out an acceptable structure. And while these negotiations were underway, the Japanese sprung a surprise by asking for a minority stake in Big Bazaar if and when FDI is allowed. This was their pre-condition, before signing a deal with Biyani for the back-end sourcing deal. Without a right of first refusal, they said there could be no deal.

Clearly, the astute Japanese team has also figured out the real jewel in Biyani’s crown. But for Biyani, this could be a deal breaker.

If Mitsubishi comes in as a financial investor into Future Value Retail, where Big Bazaar business is currently housed they are unlikely to pay top dollar or add any real value in scaling the business.

More importantly, it could complicate matters in case Biyani lines up a possible three-way alliance with strategic investors like, say, Walmart and the Bharti group. Like the Pantaloon deal with the Birla’s, he is likely to retain some stake—that allows him to cash in on the substantial upside a couple of years down the line.

It is unlikely he will show his hand right away he’ll keep the Mitsubishi deal in play for a while.

Once the Pantaloons and FCH deals are complete and his plan to offload stake in the insurance business succeeds, there’s every chance that Biyani could abort the deal with the Japanese on some pretext or the other and instead wait it out for a strategic investor like Walmart to step into the ring and pay a king’s ransom for the real jewel in his crown.

First Published: Jun 18, 2012, 06:29

Subscribe Now