SpiceJet's second take-off

Last year, entrepreneur Ajay Singh stepped in and pulled the carrier he had helped launch 10 years ago from the brink of collapse. It is early days yet, but the turnaround he is scripting may see the

On December 16, 2014, New Delhi-based aviation entrepreneur Ajay Singh pushed every button possible to give the company he had co-founded—low-cost airline SpiceJet—a new lease of life. From meeting with bureaucrats at the Ministry of Civil Aviation to addressing the concerns of industry stakeholders like US-based aircraft manufacturer Boeing Co and arranging for Rs 100 crore as working capital, Singh managed to do it all in less than 24 hours. This urgency was warranted: SpiceJet was on the verge of shutting down as it had no money to fly its planes.

In the two days before Singh’s rushed efforts, on December 15 and 16, SpiceJet had halted its flights, which lead to chaos at airports across the country. The media reported extensively on how passengers vented their anger on the airline’s staff, who themselves were a frazzled lot as they hadn’t been paid their salaries for at least a month. “I felt really bad because, after all, it [SpiceJet] was my baby,” recounts Singh.

Although he only had a residual 2.5 percent stake in the company, it was painful for the 49-year-old to see the airline he had launched (along with the UK-based Kansagra family) in May 2005 on the brink of collapse. Singh had stepped down as director of SpiceJet in August 2010, two months after Kalanithi Maran, Chennai-based billionaire and chairman and managing director of Sun Group, became the single largest shareholder in the airline.

Politically-linked Maran—he is connected to Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), Tamil Nadu’s main opposition party, while his brother Dayanidhi was the Union minister in charge of the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology between 2004 and 2007—had bought a stake of 37.4 percent in SpiceJet from the airline’s then two biggest shareholder investors US financier Wilbur Ross and the Kansagra family for about Rs 750 crore. He later increased his shareholding to over 50 percent by buying shares in the open market. “Maran wanted to run it [the airline] his way. So that was it,” says Singh.

When he left the company, the airline was profitable and had cash reserves of Rs 630 crore in the bank. The following years, however, saw its fortunes dwindle. FY11 would be the last time the carrier reported a profit—a little over Rs 100 crore on a full-year basis. At the end of FY14 SpiceJet reported a loss of Rs 1,003.24 crore, and continued to pile on the losses (of Rs 700 crore) between April and December of FY15. By the end of FY15, the airline had accumulated losses to the tune of Rs 2,500 crore (FY12-FY15). Meanwhile, rival IndiGo, the largest airline in India with a market share of 35.3 percent, reported a profit of Rs 1,304 crore in FY15.

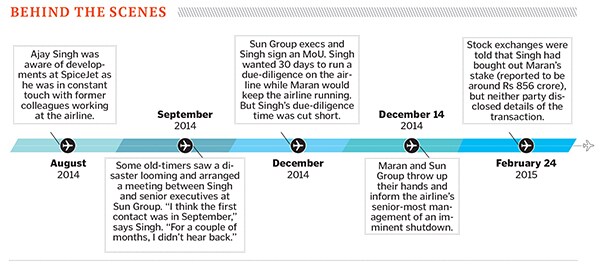

Concerned with what was happening, the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) on December 5 directed SpiceJet to not collect money on bookings for flights beyond a month. With that, the airline’s last possible revenue stream was turned off. And then, in mid-December, during peak season, oil marketing companies decided not to refuel SpiceJet’s aircraft until it had cleared its dues. It was literally the end of the road for the carrier. “I got involved that day [December 16] itself even though officially and commercially the takeover process happened in February. Maran’s team told me, ‘You do what you have to do and just take over’,” recalls Singh.

A year later, he has a different story to narrate. SpiceJet is generating enough cash to fund its day-to-day operations and for two successive quarters (Q4 of FY15 and Q1 of FY16), the airline has made profits of Rs 22.52 crore and Rs 71.85 crore respectively.

Since taking over as chairman and managing director, Singh has pumped Rs 850 crore into SpiceJet (which does not include his buy back of Maran’s 58.4 percent stake), raising the money through various financial instruments. “It’s a combination of low-cost debt and supplier credits,” he says.

In February 2015, the Indian stock exchanges were informed that Singh had bought out Maran’s stake (reported to be around Rs 856 crore), but neither party disclosed the financials of the transaction. “Some of those details are still covered by confidentiality agreements between the seller and me.” His stake in the airline, as of the quarter ended June 2015, stood at 60.31 percent.

And to show his commitment to turning around the carrier’s fortunes, he has decided not to take any remuneration until the airline becomes profitable on an annual basis.

Dhiraj Mathur, partner-aviation at consultancy firm PwC India, believes SpiceJet has indeed weathered a prolonged storm. “[Since Singh’s takeover], it has made profits, placed orders for more aircraft, has been able to retain a majority of its workforce and has even started to increase its operations,” he says.

Industry stakeholders, too, have given their stamp of approval. Aircraft manufacturer Boeing Co, with whom SpiceJet has placed an order for forty-two 737 MAX-8 aircraft valued at $4.4 billion in March 2014, says the low-cost carrier continues to be a valued customer. “The aviation market in India is very competitive and dynamic. Boeing will continue to support and work with SpiceJet for its current and future fleet needs,” says Dinesh Keskar, senior vice president, Asia Pacific and India Sales, Boeing Commercial Airplanes.

SpiceJet’s turnaround has not gone unnoticed in India’s fiercely competitive aviation industry. “Any turnaround is a good thing for the industry as a whole. We are all in it together and you never want to see anyone fare badly,” says Mittu Chandilya, CEO of low-cost airline AirAsia India. Another collapse on the heels of cash-strapped Kingfisher Airlines, which shut down operations in 2012, would have been a huge blow to the industry. “They [the Ministry of Civil Aviation] told me that it would be terrible news for the aviation sector if SpiceJet were to shut down, too. From my perspective, it was extremely important that we do not have a repeat of what happened to Kingfisher Airlines,” says Singh, who, like Maran, is politically well connected.

Singh was in charge of Narendra Modi’s communication campaign (print, TV, radio and billboards) for the 2014 elections, and is also the brain behind the slogan ‘Ab ki baar Modi sarkar’. While Singh is not a BJP member, as a strategist he has played a key role in the party’s election campaigns since 1998. He was also in charge of the media publicity of former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s famous Lahore bus ride in 1999.

What Singh did not have, though, was a background or expertise in the aviation industry.

The rise of Singh

Singh comes from a well-to-do family that has a flourishing mid-size business with interests in fashion, real estate and finance. A student of St Columba’s School in New Delhi, Singh graduated from IIT-Delhi with a BTech degree. In 1988, he went to Cornell University in the US to study business management.  While the chain of events after Singh’s return to India in 1990 is not very clear, by the mid-’90s he had bagged a seat on the board of the Delhi Transport Corporation (DTC). With 40,000 employees and only 300 buses, DTC was on its way to becoming a defunct organisation. “The job was really to try and see if we could revive that corporation,” recalls Singh. In three years, he transformed DTC into a self-sustaining corporation with a fleet of 6,000 buses.

While the chain of events after Singh’s return to India in 1990 is not very clear, by the mid-’90s he had bagged a seat on the board of the Delhi Transport Corporation (DTC). With 40,000 employees and only 300 buses, DTC was on its way to becoming a defunct organisation. “The job was really to try and see if we could revive that corporation,” recalls Singh. In three years, he transformed DTC into a self-sustaining corporation with a fleet of 6,000 buses.

His efforts in turning around the loss-making company caught the attention of the late BJP leader Pramod Mahajan. As the Minister of Information and Broadcasting in the Vajpayee-led BJP government, Mahajan roped Singh in as an advisor (with the rank of joint secretary) to help revamp the state-run television network Doordarshan. And when Mahajan took charge of the telecom portfolio, Singh moved along with him. There, he got a bird’s-eye view of the mobile telephony explosion in India after Vajpayee’s government introduced various measures to lower call rates. The experience would hold him in good stead when he entered the nascent low-cost commercial airline business.

In 2004, when Vajpayee was seeking a second term in office, Singh was back as a strategist in the party. “When they [the BJP] lost that election, I was getting a lot of pressure from my family to get back to doing some ‘real business’ or get back to the family business, which was going fine,” he says.

It was around this time that he was introduced to the Kansagra family, who had bought the erstwhile ModiLuft airline (it had been operational between 1993 and 1996) from industrialist SK Modi in 1999-2000. But the Kansagras had been held up for five years, clearing legal cases against ModiLuft. When Singh met them, he was excited about taking on the challenge of running a carrier. “The idea of starting a low-cost airline came in only after Mr Singh came on board. Before that we were positioning ourselves as a full-service airline,” says GP Gupta, chief administrative officer at SpiceJet, who has been with the carrier since 2001 when its legal name was still ModiLuft.

When Singh got the offer to take management control and launch an airline, he was reminded of India’s mobile telephony boom. “Air fares were extremely high and as a consequence, very few people used flights to commute,” he says. Fifteen years ago, the average cost of a one-way ticket from New Delhi to Bengaluru would be between Rs 12,000 and Rs 13,000. However, Air Deccan—India’s first low-cost carrier that launched in 2003—proved that the same ticket could be bought for half the price. Singh was quick to grasp the potential of this model, and launched India’s second low-cost carrier.Air Deccan’s founder, Captain GR Gopinath, describes Singh as an astute businessman. The two met frequently when they were competitors. “He [Singh] has a very sharp mind and business instinct, and knows the low-cost airline space well,” he says. But unlike Gopinath, who had built a sizeable air charter business before going the commercial route, Singh had no experience in the aviation industry. “I never imagined I would be an aviation entrepreneur,” he says.

In the interim years between his departure and re-entry into SpiceJet (2011 to 2014), Singh dabbled in many ventures—some successful and others not quite. He bought a defunct Daewoo Motors factory in Surajpur, Uttar Pradesh, with plans of establishing an auto components manufacturing facility. That hasn’t happened yet. He also bought a controlling stake in public transport company Star Bus Services, which operates a city bus service in New Delhi. He has funded a few technology startups, including i2n Technologies, a nano-science-focussed startup that is based out of the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru.

Singh continues to remain invested in all these ventures and still nurses a dream of starting an auto components facility. But now that he’s in the pilot’s seat, his attention is on SpiceJet’s future.

The downfall

In his assessment, SpiceJet’s chief financial officer Kiran Koteshwar believes that following Maran’s takeover, the airline flew into a perfect storm. “Oil prices were on the rise, the dollar had started to appreciate against the rupee, and the domestic economy had started cooling off. In that period, the Indian aviation industry started seeing negative growth. All of this was compounded by things we as an airline did wrong,” says Koteshwar, who joined the company in 2007.

Between FY11 and FY14, it saw a capacity growth (a combination of growth in routes and aircraft) of 35 percent year-on-year. The company had spread itself too thin. In the low-cost model, the ideal ratio is two aircraft to one airport. Under the new management, SpiceJet started moving away from this model: With a fleet of 58 aircraft, it was operating in 59 destinations.

The airline added routes such as Delhi-Guangzhou, Delhi-Riyadh, Varanasi-Sharjah, which in hindsight “didn’t make sense”, says Sanjiv Kapoor, COO of SpiceJet, who joined the airline in November 2013. “The reason these routes didn’t make sense was because there wasn’t natural traffic demand or sufficient yield quality to make them profitable.” Also, in the low-cost model, you don’t have business- and first-class to push up revenues.

On routes like Delhi-Guangzhou or Varanasi-Sharjah the average one-way flying time was five to six hours and the round-trip was 11 to 12 hours, including ground time. “That means one route is occupying an entire aircraft, and for a low-cost model it is very difficult to sustain it,” says Kapoor. Within three months of joining the airline, he did away with these routes.

What he also noticed was that from February to September 2013, the carrier had offered too many seats at highly discounted prices. But, to be fair, it was not just SpiceJet that was guilty of adopting this strategy. “All airlines got burnt through these less-than-well-thought-out sales and around September we [all the carriers] went to the other extreme and raised fares by 20 to 25 percent. By doing so, we significantly suppressed demand in a very price-sensitive market,” says Kapoor. While SpiceJet is still big on sales, he says there are “fences” and “restrictions” in place to prevent a repeat of 2013.

SpiceJet was facing other structural cost challenges. “We had a few long-term contracts with regard to engineering and maintenance, which were disadvantageous to us,” says Kapoor. For instance, SpiceJet bought 15 medium-range turboprop Q400 aircraft from Canadian aircraft manufacturer Bombardier Aerospace. At present, around Rs 1,200 crore in debt on the airline’s books is related to the purchase of the Q400s. “I would never have had a dual aircraft model. Now that I have inherited these aircraft, and as long as they can make money, I’m prepared to live with it,” says Singh.

Kapil Kaul, CEO of CAPA South Asia, an independent aviation consulting, research and knowledge practice firm, sums up all that went wrong. “SpiceJet’s downfall was largely due to serious under- capitalisation, lack of strategic depth in its business plan, very poorly structured contracts, no accountability at the top and very poor promoter and board oversight,” he says.

SpiceJet also lacked the strong leadership it needed to guide it through those turbulent years. One point that seems to emerge from both rank and file as well as industry experts is the lack of visible leadership by Maran and his Sun Group in running the airline.

“If Mr Maran himself was the CEO full time he would have probably done a good job,” says Captain Gopinath.

Sun Group’s CFO SL Narayanan did not respond to emails and texts from Forbes India regarding this story.

Chandan Sand, vice president (legal) and company secretary at SpiceJet underscores the importance of the promoter, especially in the aviation industry. He argues that it helps if the people who make decisions are physically present. The Sun Group was based in Chennai, and it was difficult for its management team to run the Gurgaon-headquartered SpiceJet. “It is important that the promoter or the head is at a close proximity so that decision making can be quick,” says Sand. For example, in matters of aircraft purchase and lease, he believes it is mandatory for the promoter to step in and take part in the final round of negotiations.

The logic is simple: With the promoter at the negotiating table, the seller or lessor gets the complete picture of the carrier’s long-term vision, strategy and commitment. This gives the airline more leverage in striking better deals. Industry sources say that at IndiGo, the promoters sign off on such contracts, which have proven to be immensely beneficial to the operations of the airline.

Koteshwar says the decision-making at SpiceJet now gets done in five to 10 minutes as against the earlier five-month lag.

“The benefit with him [Singh] is that he is hands-on,” adds Sand.

When you try to search for parallels between the downfall of Kingfisher Airlines and that of SpiceJet there are many, but one that stands out is the similarity between the promoters, Vijay Mallya and Kalanithi Maran. With no prior knowledge of running an airline or grasping the difficulties of operating a carrier in India, they both showed a determination to own an airline like a trophy asset, say analysts and industry experts.

“I agree with that. The fact that it has been a trophy asset for some people has actually distorted the market much as Air India distorts the market by having the public fund its losses on a continuing basis,” says Singh.  A partial turnaround

A partial turnaround

With two consecutive quarters of profit, Singh isn’t one to get carried away by the numbers. He admits that so far, it has been a “partial turnaround” for SpiceJet.

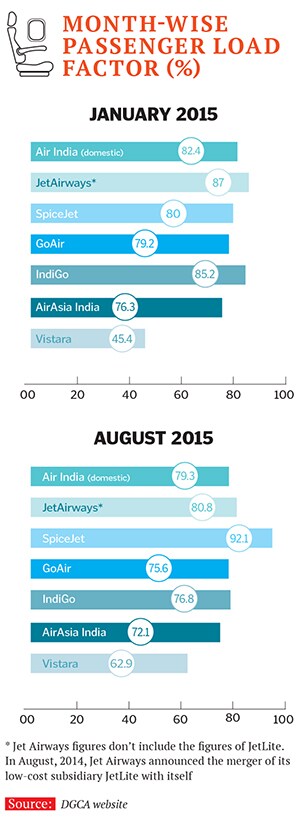

According to Amrit Pandurangi, senior director with Deloitte in India, the carrier’s return to profitability on a quarterly basis is being aided by factors such as an overall growth in domestic air travel and lower aviation fuel prices. While price of global crude has dropped by over 50 percent in the last 12 months to under $50 per barrel, in the first two quarters of the ongoing calendar year, passenger traffic has grown by 19 percent and 20 percent respectively. In fact, IndiGo’s FY15 profit saw a fourfold increase over the previous year, aided by a combination of lower fuel prices, higher revenues, and interest income earned on fixed deposits. “A combination of this positive environment, which is benefiting other airlines as well, and the advantage of receiving fresh capital infusion has helped SpiceJet,” says Pandurangi.

Incidentally, its performance in the fourth quarter of FY15 got a boost when SpiceJet got lucky with a net gain of Rs 61 crore on an insurance claim on one of its Q400 aircraft, which was involved in an accident at the Hubballi airport in Karnataka. While terming SpiceJet’s performance as “remarkable”, CAPA’s Kaul says “consistent profitability” over next four to six quarters will be the key to a genuine turnaround.

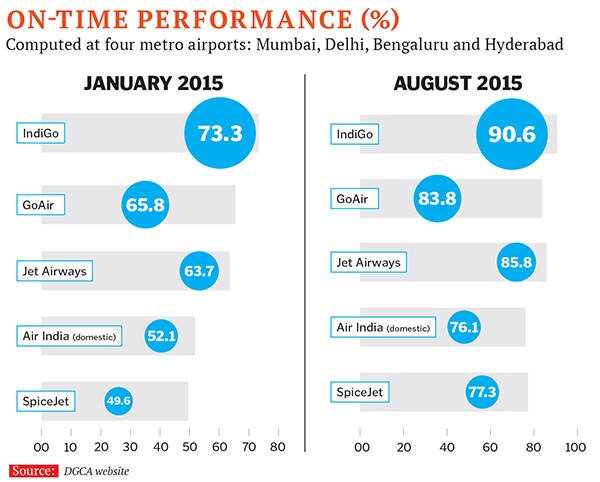

Singh, too, is realistic and pragmatic about the company’s performance. “The direction in which we are headed is right, but there is a lot more to do,” he says. For one, he has to focus on maintenance costs. In India, the highest cost for an airline is fuel, followed by aircraft maintenance and engineering. The maintenance cost per available seat kilometre (ASK) of SpiceJet is a high 90 cents, compared to IndiGo’s 34 cents, as per data from a recent Draft Red Herring Prospectus it has filed.

There is plenty of room for improvement in other areas, too. For instance, Rajesh Magow, co-founder and CEO-India of MakeMyTrip feels SpiceJet has not yet perfected its revenue management. “But I do think that it is a lot better [today] than what it was last year,” he says.During its heaviest losses in FY14, its net margins were as bad as negative 24 to 25 percent. “Now, we are positive 6.5 to 7 percent, which is a net change of 30 to 31 percentage points,” says Kapoor. “About half of that change has come from the cost side, significantly driven by lower fuel prices, while the other half has come from the revenue side where we have done smarter things.” It has introduced popular measures like special discounted fares to fliers carrying only cabin baggage and allowing passengers to carry cabin baggage weighing up to 12 kg, with a fee of Rs 250 per kg for baggage in excess of 7 kg.That said, SpiceJet has a long way to go before it can compete with IndiGo. And Singh isn’t afraid of giving credit to his competitors. He thinks IndiGo’s promoters have done a fabulous job in running the airline. “IndiGo is planning to raise [an initial public offering] at a $4 billion valuation. SpiceJet is currently valued at $250 million.”

In mid-December last year, SpiceJet’s share price was Rs 13.15. As of October 6, 2015, the airline’s share price was Rs 30 (a growth of 130 percent), giving it a market capitalisation of Rs 1,798.35 crore ($275 million).

IndiGo has been profitable since 2009, despite having started its operations a year after SpiceJet and GoAir. By placing big aircraft orders, IndiGo went after scale. “It had a blueprint that was ambitious, very long-term and clearly laid out,” says Kapoor. It helps that there hasn’t been any changes at the promoter level, which has given it the required stability to succeed.

While in every aspect of the business IndiGo’s numbers dwarf that of SpiceJet’s, Singh isn’t perturbed. Market share isn’t his immediate goal he’s chasing “profitable” and “healthy” growth. He believes that there is plenty of room for growth as only 1.5 percent of the country’s population travels by air.

“The potential in India is very high, as the overall economy continues to develop and the middle-class continues to grow. However, airlines will need to continue to watch fuel prices as well as foreign exchange rates in order to run their operations profitably,” says Keskar of Boeing.

With oil prices remaining low, the time is right for airlines to expand their operations. And that’s exactly what Singh is doing at SpiceJet. Without divulging details he says SpiceJet is in the market to place a “larger number of orders” for the bigger single-aisle jet aircraft as well as the smaller turboprop aircraft. “We will use this opportunity to get our structural costs right,” he says.

In the meantime, the airline’s top management is changing the way business is being done. SpiceJet is restructuring departments such as in-flight catering, its training academy and its IT department, (which has built software products that it can also monetise) into strategic business units. The end goal is to de-risk the airline from its core business, which is selling seats. Cargo, for instance, is being looked at as a supplementary revenue stream as the management looks to maximise the usage of its aircraft belly space.

Koteshwar says the company is now a “sales driven organisation”. He explains: “Initially, we would motivate employees who helped us reduce costs now we incentivise those who grow the business.” The entire approach is being driven bottom-up rather than top-down.

And morale is high. Having celebrated its 10th anniversary on May 23 this year, SpiceJet is proving to be the proverbial cat with nine lives. The more pertinent question though is whether Ajay Singh has the ability to fly it back into the black. The entrepreneur is in no hurry to leave his seat at the helm this time around. “The first disengagement was quite painful. I think I’m here for the long term,” he says.

First Published: Oct 26, 2015, 06:46

Subscribe Now