Shalimar Paints shifts focus to the Decoratives Business

New chief executive Sameer Nagpal aims to focus India's oldest paint company in the decorative paints market, where margins are significantly higher than in the industrial segment

It is early days still but Gurmeet Singh Narula, a Shalimar Paints dealer since 1970, has a spring in his step. For the first time in 20 years, his paint deliveries are on time, the quality of paint has improved over the last five months, and customers are asking for the paint by its brand name, says Narula, who averages a crore in monthly sales. His revenues haven’t gone up meaningfully, but he’s confident that it’s only a matter of time before they do. “In terms of product quality, you can now replace Shalimar with Asian Paints [market leader], and people won’t know the difference,” says the Delhi-based dealer.

Such high praise from one of the company’s largest dealers is an endorsement for the country’s oldest paint maker. Set up in 1902 in Calcutta, Shalimar was once India’s largest paint company. “It was the Asian Paints of the 1950s and 1960s,” says an analyst who tracks the sector. But its decline began in the early ’90s. Its shift in focus from the decorative paints (used in homes) space to the industrial market (paint for bridges, factories, automobiles)—where margins are low and business lumpy—reduced Shalimar to a shadow of its former self.

In the five-player paint industry (excluding regional companies), Shalimar is the smallest, behind Asian Paints, Berger Paints, Kansai Nerolac and AkzoNobel (formerly ICI Paints). It closed last year with Rs 483 crore in sales compared to Asian Paints’ Rs 10,418 crore, and its market cap is a paltry Rs 179 crore.

It’s little wonder, then, that Shalimar’s current owners—board members Ratan Jindal, who runs Jindal Stainless Steel, and Girish Jhunjhunwala of Hind Group—have put the company on the block several times in the last decade. But no deal ever took place. And now its board of directors is attempting one last shot at turning Shalimar’s fortunes. In May 2013, they roped in Sameer Nagpal, former vice president of industrial products company Ingersoll Rand (India), as CEO and managing director.

Nagpal, 45, has been a given a free rein to turn around Shalimar, and he’s not pulling his punches. He’s mapped out a risky strategy, because of which the company’s topline dropped by Rs 47 crore in 2013-2014. The slump was mainly due to write-offs and delay in product launches (as quality control protocols were being put in place). With his house now in order, Nagpal is chasing a 20 percent jump in revenues this year.

From Industries to Homes

Nagpal has inherited a company that was once at the forefront of technology: It was the first to paint a fighter aircraft for the Indian Army, and had also received a contract to paint the Rashtrapati Bhavan. Such work, however prestigious, has very low margins (of about 2 percent).

Nagpal has a clear mandate to increase company profitability and improve valuation for investors. To achieve this, he has shifted Shalimar’s resources to the more profitable and fast expanding decorative paints segment which, according to ratings company Nielsen India, is worth Rs 20,000 crore (out of the Rs 30,000-crore Indian paints market).

When he delved deeper, Nagpal found that Shalimar’s product mix was skewed towards the low-margin industrial segment (Rs 10,000 crore). Though it was a big player in the industrial coatings business, it was absent from the higher-margin oil and auto paints space. Shalimar, however, has no immediate plans to enter this particular segment. The CEO realises that muscling his way through the segment requires heavy investments and breaking long-standing customer relationships. Kansai Nerolac, for instance, has been supplying to Maruti Suzuki for over two decades. Instead of pouring money down lost causes, Nagpal started plugging the holes in Shalimar, the biggest of which was poor product quality and lack of brand recall.

Nagpal, who has 15 years of experience at Carrier Corporation (the AC manufacturer), does not come from the paints industry, and was able to approach these problems with a fresh mindset. “While it was good, it also slowed me down,” he says.

His initial research threw up many interesting insights, the most important of which was the discovery that it’s not always the customer, but the painter, who decides what brand to use. Painters care about timely availability and quality it is their credibility at stake. Simply put, if they run out of paint in the middle of painting a wall, they need a replenishment of the exact shade of paint, otherwise they have to repaint the entire wall.

It was here where Shalimar had stumbled: Even though it never stopped manufacturing products such as emulsions, protective coating and top coats, its quality diminished with each passing year.

Improve Quality Win Back Trust

“In the decorative paints business, product equivalence is just the entry ticket to the game,” says Rajiv Jain, former managing director of ICI, which owned ICI Paints (renamed AkzoNobel). “Your product must be equivalent or better.” Paints are fairly straightforward products. Atul Choksey, part of the promoter family that led Asian Paints for 15 years till 1998, tells Forbes India that there’s hardly any difference in the quality of paint from large companies. “Tinting machines where you mix the base and primer will give you the exact shade you want. What is non-negotiable, however, is quality,” he says.

At Shalimar’s plants, Nagpal found that due to lack of quality checks and late payments to suppliers, raw material was not up to the mark. “They [factory managers] would often delay payments and then substitute with another supplier,” he says. He put an end to this, rewrote the company’s quality control policy, and made sure that every product was put through new checks and balances. Today, all products, after going through the quality tests, are signed off by him. Only then are they branded with the company’s new logo.

But Shalimar’s problems were not limited to quality control. There were issues at the distribution level too. Here, Nagpal pushed for the streamlining of depots that earlier worked with no strategic planning. (Products from its factories in West Bengal, Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh are sent to depots across India from where they are shipped to distributors and painters.) He introduced one more layer in the form of a centralised distribution centre to help declutter its depots. And, most importantly, he set up a forecasting cell to give the company an idea of how future demand will play out, which would enable factories to take decisions accordingly. “As a consumer company, we did not have a forecasting cell. Among the first things I did was put one in place,” says Nagpal.

He also had some cleaning up to do on the dealer front. Of Shalimar’s 8,000 dealers, 6,000 were doing business worth only Rs 10 lakh (or less) with them. (Narula is one of its rare exclusive dealers.) Such small scale of business leads to zero brand loyalty. To make matters worse, with slow sales velocity, dealers took as many as 90 days to pay Shalimar. (For Asian Paints, they do it within a month.)

Nagpal decided, with his limited resources, to create some pull for the brand among dealers as well as painters. He regained lost ground with painters by holding regular workshops—a common practice among brands like Asian and Nerolac. Dealers were incentivised to recommend Shalimar, and were offered better terms of trade if they reached certain targets. This, along with dealer engagement, led to a 34 percent jump in decorative paints sales for its top 745 ‘club’ dealers. Despite lowering the credit period, sales increased by 0.5 percent last year for the other dealers in the decoratives business. Add to this, Shalimar still gives the best margins, and it is likely that dealers will continue to recommend its products if quality isn’t an issue.

Branding and advertising

Nagpal’s efforts in the last one year have ensured that Shalimar’s competitors are taking notice, but the company is still too small for them to worry about.

After setting up systems such that quality products reach dealers in time through a streamlined distributing process, the CEO has now turned his attention to consumers he wants them to know his brand. When he joined Shalimar, he says, “everyone knew of Asian Paints, but no one knew of any other company”. To rectify this, Shalimar has invested in a Rs 10-crore advertising campaign crafted by Wieden+Kennedy (the company that made Nike a household name and has worked with the homegrown Indigo Airlines and Forest Essentials).

Nagpal, in an effort to conserve cash, may not spend all the money this year, but plans an aggresive branding strategy in future. Shalimar’s campaign, which rolls out next month, will showcase its new branding through print, television and social media.

Tying up loose ends

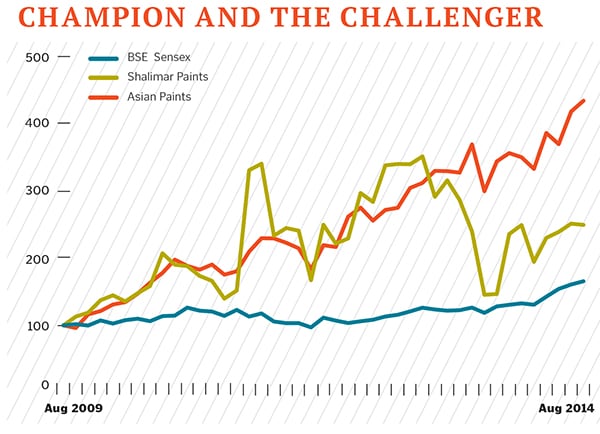

Analysts reckon it’s too soon to pronounce a judgement on whether Shalimar will succeed. In its earlier avatar as an industrial paints company, it, despite its depressed profitability, showed consistent topline and bottomline growth. From 2002 to 2008, the stock even outperformed Asian Paints on the Bombay Stock Exchange. And in the last 10 years, it has given a compounded annual growth rate of 21 percent. Still, given its margin profile of 2 percent versus the industry average of 11 percent, its valuation is a fraction of its peers’. “We are convinced that the decorative [paints] market can grow at 15 percent for the next five years,” says Hemant Patel, ED - consumer, Axis Capital.

To reach his target—20 to 25 percent topline growth—Nagpal has spent lavishly on the right people. He’s hired several industry veterans from rivals, including a manufacturing head from Asian Paints. Employee costs have thus risen 33 percent to Rs 38 crore. The company has also instituted an employee stock ownership plan for its senior management. In effect, if the business doesn’t perform, there could be a heavy price to pay.

A year into the new strategy, the market is giving Nagpal the benefit of the doubt. Shalimar’s share price, which fell drastically last August from over Rs 100 to Rs 50-55—after Nagpal had come on board—is now at about Rs 95.

With the initial glimmer of a turnaround, Nagpal is looking for Rs 100 crore in private equity money which he will invest in the brand. He wants to update the company’s IT backend, depots and tinting machines, each of which costs Rs 1 lakh. He also expects a new investor to come in at a Rs 400 crore company valuation—twice its present market cap.

Getting that will be a huge affirmation of his new strategy. And it will also keep him on his toes for the next five years.

First Published: Sep 17, 2014, 06:49

Subscribe Now