Reclaiming glory: Nokia reloaded

Finnish handset maker Nokia is making a bold comeback in its new avatar, but can it relive its glory days?

Ajey Mehta believes in showing perseverance in the face of adversity

Image: Amit VermaA mechanical engineer, it’s easy to assume, would be obsessed with processes. Ajey Mehta, an alumnus of the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras, defies the stereotype. As vice president and country head (India) of HMD Global—the Finnish company with a licence to sell Nokia-branded phones—Mehta is not consumed with physics. He is more immersed in reviving the chemistry of the Nokia brand with consumers.

For somebody with a marketing and finance background from the Indian Institute of Management, Calcutta, Mehta is again an aberration when it comes to numbers. After spending over 13 years with Nokia and Microsoft in different capacities, he reckons numbers are a means and not an end.

“It’s neither in my DNA nor in the company’s DNA to thump one’s chest,” says Mehta, alluding to the startling pace with which Nokia broke into the top five feature phone brands in India within a year of re-entering the country.

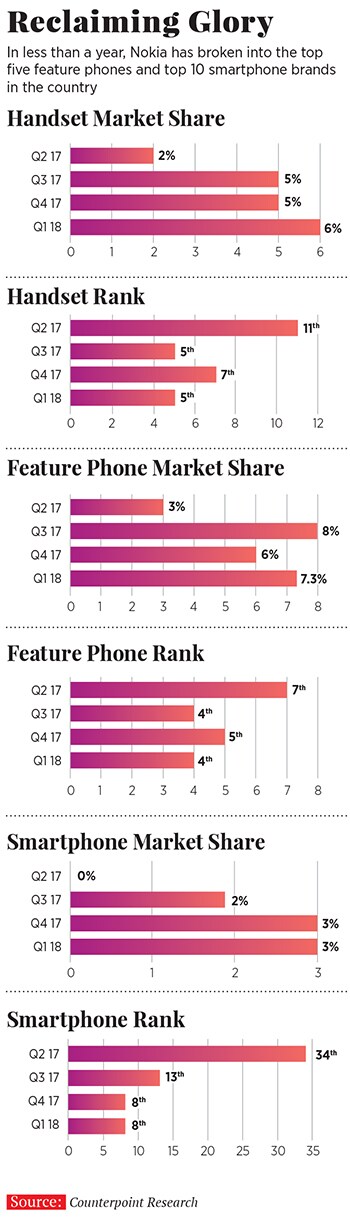

With a 7.3 percent market share, Nokia has become the fourth biggest feature phone maker during the first quarter of this year (January-March 2018), according to market research firm Counterpoint Research. The smartphone numbers too are impressive: From 34th in the pecking order in the second quarter of last year, the Finnish company has moved to eighth position with a 3 percent market share. Though 3 percent looks meagre, consider that, with just a 3.4 percent share, Chinese label Honor is the fifth largest smartphone brand in India.

For a brand that once overwhelmingly dominated the Indian market, but lost out to Korean giant Samsung and much nimbler Indian players led by Micromax, the comeback with a new owner and new operating system—Android—sounds fairytale-ish. Mehta, however, assures you it’s been anything but that.

“I don’t know Finnish, but there’s one Finnish word that I swear by: Sisu,” he says. Sisu, he lets on, is perseverance in the face of adversity. “At the core of Nokia is Sisu, the value of never giving up under adverse circumstances,” says Mehta.

The preparation for the comeback—India is already among the top three markets for Nokia—was intense. With good reason. At stake was the (lost) pride of the brand that was once the darling of the masses for its long-lasting battery, ease of use, the Snake game and the famous ringtone based on the Francisco Tárrega waltz. Most important, however, at stake was the prized Indian market.

Reconnecting People

For starters, Nokia revisited its old tagline—Connecting People—and gave it a spin. “The idea was to go back to the people and find out what they wanted rather than giving them what we wanted,” says Mehta, adding that consumer immersion sessions were conducted to figure out the mood of the users. The insights, he adds, were duly incorporated.  Take, for instance, Nokia 7 plus. Six layers of ceramic paint on the back and a double-anodised aluminium frame addresses some of the concerns voiced by participants. The ceramic back prevents the handset from slipping, does not leave fingerprint marks and is transparent enough to ensure that the phone has to work less hard to connect with the network this means a longer battery life.

Take, for instance, Nokia 7 plus. Six layers of ceramic paint on the back and a double-anodised aluminium frame addresses some of the concerns voiced by participants. The ceramic back prevents the handset from slipping, does not leave fingerprint marks and is transparent enough to ensure that the phone has to work less hard to connect with the network this means a longer battery life.

Pranav Shroff, director (global portfolio and product management) at HMD Global, shares more insights. One of the pain points narrated by participants during the immersion sessions, Shroff recalls, was a drop in core performance. While phone makers were shifting towards bigger screens and faster operating systems, it was not reflecting in the core performance of the handset, which used to slow down after a couple of months. Another irritant, he recounts, was the perception of Android not being secure and coming with preloaded apps that eat into the memory. “We worked on a differentiated offering based on the idea that less is more,” adds Shroff.

Call it nostalgia marketing or the art of selling a slice of history, HMD Global has so far played all its cards to perfection by relaunching Nokia in a country where the latent brand equity is still intact. “People are passionate about the brand and its values,” reckons Shroff. And that is reflected in the headquarters of HMD Global in India.

The fifth floor of Pioneer Urban Square, a multi-storey swanky building in sector 62 of Gurugram, is draped in the past and present. While visitors are greeted with a huge cutout of Nokia’s iconic 3310, a TV screen showcases every minute detail of design engineering that the latest Nokia phones boast. The interiors, including pillars and furniture, bask in vibrant hues of yellow, orange and red.

Sitting inside a small corner meeting room, Mehta explains why the past, though crucial, is not integral to the brand’s future. “The brand has played an important part in giving us initial volume. But it can only give you that much,” he says. “If you don’t have products that deliver, no amount of branding and nostalgia can help.”

Nokia’s comeback gets a thumbs up from analysts. That the brand has managed to rise in the rankings in both the feature phone and smartphone segments is impressive, points out Shobhit Srivastava, research analyst at Counterpoint. “Particularly if you consider the intense competition in the Indian mobile phone market.” The adoption of Android and brand value have worked together for Nokia in smartphones.

“It has also rekindled consumer sentiments by relaunching new avatars of old Nokia phones,” adds Srivastava, explaining the reasons why Nokia couldn’t click in its last avatar with Microsoft: Lack of an exhaustive app ecosystem on the Windows and Symbian operating system. While the company tried hard with its Lumia smartphones and launching devices with differentiating factors such as enhanced camera and music, they just didn’t click with consumers.  Pranav Shroff says people are still passionate about brand Nokia and its values

Pranav Shroff says people are still passionate about brand Nokia and its values

Image: Amit Verma

Nokia’s ‘Dumb’ Advantage

What has also aided Nokia’s revival—globally as well in India—is the resurrection of the feature phone. Early this year in February, market research firm IDC declared that HMD Global has emerged as the second biggest feature phone maker in 2017 by shipping 52.9 million handsets. “The Nokia brand is proving to be resilient among feature phone users,” analyst Francisco Jeronimo tweeted.

The global feature phone market, according to a recent study by Counterpoint Research, grew by 38 percent annually in the first quarter of this year, driven largely by strong shipments of Reliance Jio in India and the return of Nokia HMD. India alone contributed to almost 43 percent of the total feature phone shipments in the first quarter, the report added. With 14 percent, Nokia was the second biggest feature phone player globally after Jio. Nokia sold more than 70 million phones—feature and smart—globally, including in India, last year.

“There are still around half-a-billion feature phones sold every year and these continue to serve the needs of the roughly 2 billion feature phones users globally,” Counterpoint’s Srivastava posted on his blog in May. This is still a huge market catering to a diverse user base, many of whom still prefer feature phones over smartphones, he explains, pointing to plausible reasons for the loyalty of consumers towards feature phones. Longer battery life, lower cost, lighter forms and preference for simplicity were some of the top reasons cited for the success of feature phones globally.

Back home in India, the feature phone market doubled in the first quarter of this year, even as the smartphone market remained flat. Nokia, with its 7.3 percent market share, raced to fourth position in India, according to Counterpoint Research.

The growth, as it turns out, is not just a one-quarter aberration. From 3 percent in 2016 to 13 percent growth in 2017, the feature phones market has exploded in India. The rise of 4G feature phones is likely to provide a further impetus. Bottom-of-the-pyramid (BoP) users who are using basic voice services on mobile phones and can’t afford a smartphone or an expensive data plan will drive the next phase of handset growth.

“They can now access 4G internet for the first time, with key internet capable apps and services from an operator’s expanding ecosystem as well as popular third-party companies,” Srivastava contends. Companies like KaiOS and Reliance Jio are working to add more value to the 4G feature phone, making it more appealing for BoP users with vernacular content and quality smartphones priced below $40 (₹2,700 approximately). Further adoption can be driven by possible introduction of new apps such as Facebook, Google Assistant, maps, search and digital payments.

Countering Jio’s 4G ‘Storm’

However, the opportunity for Nokia to deepen its feature phone market reach is not as easy as it looks. The threat comes from Jio. Mehta is aware of the challenge.  “Right now there is a bit of a storm that’s going on. We need to see when this storm settles down and how the industry emerges,” says Mehta. “The 4G feature phone has got traction for sure. How it actually goes forward will be interesting to watch,” he adds, visualising potential scenarios. The first is that the 4G feature phone could become a niche for people who are vulnerable to upgrade to smartphones. The second possibility is that the 4G feature phone could occupy a slightly larger share of the feature phone market, and the voice and text-only phones would move down the price ladder below the ₹1,000 category.

“Right now there is a bit of a storm that’s going on. We need to see when this storm settles down and how the industry emerges,” says Mehta. “The 4G feature phone has got traction for sure. How it actually goes forward will be interesting to watch,” he adds, visualising potential scenarios. The first is that the 4G feature phone could become a niche for people who are vulnerable to upgrade to smartphones. The second possibility is that the 4G feature phone could occupy a slightly larger share of the feature phone market, and the voice and text-only phones would move down the price ladder below the ₹1,000 category.

Nokia, asserts Mehta, is bracing for a wider play. “We will have a presence in those categories that make commercial sense to us,” he says, explaining how the Nokia 8110-4G feature phone—likely to be launched in India soon—will be a potent weapon in the company’s arsenal. “It’s early days yet. All I can say is we have grown our share. We have grown quite significantly,” he beams.

The ‘significant’ growth of Nokia has also coincided with the steep fall in the fortunes of homegrown Indian players, who ironically played a pivotal role in turning the tide against the Finnish giant. Micromax led the pack.

It was in the second quarter of 2014 when the desi hustler dethroned Nokia to become India’s top feature phone brand. With a 15.2 percent market share, Micromax toppled Nokia, which saw its share slide to 14.7 percent. For Nokia, it was the beginning of the end of its second innings with Microsoft. It slipped further and finally went out of reckoning.

Shroff of HMD Global doesn’t read too much into the change in the ranking as of May 2018, with Nokia at No 4. “First, people said there was MILK (Micromax, Intex, Lava and Karbonn), which later on got replaced by LOVE (Lenovo, Oppo, Vivo and LeEco),” he says, explaining how the market has behaved over the last few years. The game initially was to offer more specifications (features) for less. “Then somebody else came and gave even more specs for less,” he says, adding that Nokia never wanted to get into that game.

Though MILK no longer poses a threat to Nokia, what might be a steep hurdle to cross is establishing the millennial connect.

The residual brand equity, feel branding and marketing experts, is not something that will last forever as it diminishes with every passing quarter. “Nokia needs to become the brand of the millennial in terms of imagery, rather than the brand of my dad and grandad,” says brand strategist Harish Bijoor. Nokia, he adds, displays the ability of being tagged fuddy-duddy. It needs to watch out for that sentiment.

Mehta, for his part, looks at the millennial puzzle as an opportunity. Conceding that a strong brand legacy can work both ways, he avers that at times, history can position the brand as ‘my earlier generation’s phone’. The task, he avers, is to ensure that Nokia stands for the same values but is positioned differently to this segment of the population. “Rendition of Nokia in the new age as well as taking on rivals in a highly competitive industry are some of the challenges,” adds Bijoor.

The biggest challenge, however, might turn out to be the same old issue that cropped up in 2011.

A new ‘Burning Platform’

In an internal memo in early 2011, former Nokia CEO Stephen Elop reportedly told his employees that the company was standing on a burning platform.  “We are standing on a burning platform… we have multiple points of scorching heat that are fuelling a blazing fire around us,” he wrote, elaborating on the threats. “There is intense heat coming from our competitors, more rapidly than we ever expected. Apple disrupted the market by redefining the smartphone and attracting developers to a closed, but very powerful ecosystem. And then, there is Android… Google has become a gravitational force, drawing much of the industry’s innovation to its core.”

“We are standing on a burning platform… we have multiple points of scorching heat that are fuelling a blazing fire around us,” he wrote, elaborating on the threats. “There is intense heat coming from our competitors, more rapidly than we ever expected. Apple disrupted the market by redefining the smartphone and attracting developers to a closed, but very powerful ecosystem. And then, there is Android… Google has become a gravitational force, drawing much of the industry’s innovation to its core.”

At the lower-end price range, Elop contended, “Chinese OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) are cranking out a device much faster than, as one Nokia employee said only partially in jest, ‘the time that it takes us to polish a PowerPoint presentation’. They are fast, they are cheap, and they are challenging us. And the truly perplexing aspect is that we’re not even fighting with the right weapons.”

Much has changed since 2011. Nokia changed hands twice: Microsoft bought it and then after its failure to run the business, struck a deal in May 2016 to get rid of the business—while Foxconn acquired the manufacturing, sales and distribution units of the Microsoft business, HMD got rights for marketing and selling Nokia-branded devices—Nokia ditched Symbian and Windows and embraced Android but the threat from Chinese vendors remains the same, especially in smartphones. In fact, it has intensified. The top five smartphone players in smartphone brands include four Chinese and one Korean. Combined, they control close to three fourths of the market.

Srivastava of Counterpoint deciphers the challenge. Nokia fits right into the mid-end segment, which is the fastest growing segment in India. “The company will face maximum competition from the Chinese players that are driving the growth,” he says.

What might give more ammunition to the brand to fight Chinese rivals is HMD Global’s latest fundraise: $100 million, giving the Finnish business unicorn status with a valuation of more than $1 billion.

“We are not going to be pushed around. We will build our brand bit by bit,” declares Mehta, stressing that the 150-year-old label has gone through several reinventions along the way.

Drawing a parallel with Kolkata Knight Riders (KKR), one of the Indian Premier League (IPL) teams that entered the playoff stage this season, Mehta asserts that Nokia still follows the first tagline of KKR: Korbo lorbo jeetbo (to do, to fight and win). KKR didn’t win the tournament, but Nokia would be glad to climb to the position the Kolkata team finished at: No 3.

First Published: Jun 08, 2018, 12:31

Subscribe Now