Putting the Shine Back Into Tata Steel

The 106-year-old giant faces the toughest challenges of its existence. Can Cyrus Mistry hammer it back into shape?

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether ’tis Nobler in the mind to suffer

The Slings and Arrows of outrageous Fortune,

Or to take Arms against a Sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them

- Hamlet, William Shakespeare

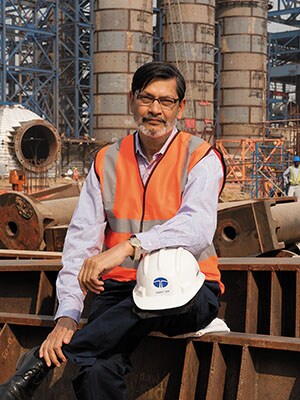

On March 3, when Cyrus Pallonji Mistry took the podium at Jamshedpur to address the assembled crowd, it was his first public appearance since he formally took over as chairman of Tata Sons in December 2012.

For Jamshedpur, and for the Tata group, March 3 is a special date: 174 years ago, Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata was born. At the turn of the twentieth century, he had displayed remarkable foresight—and stoked industrial development in India—by deciding to build a steel company here. That decision also marked a new phase for the group. It began to diversify into the entity that it is now, making everything from steel to trucks to cars to software to salt, among other things. Most remarkably, it has also earned an enormous reservoir of trust and goodwill, no easy task, in India or elsewhere.

Mistry looked relaxed, calm. No one knew what was going through his mind no surprise that, because he’s always been a bit of a recluse who keeps his own counsel. (He declined to talk to us for this story.)

It is entirely possible that Mistry’s unruffled demeanour had to do with the fact that he had already been thinking hard about Tata Steel much before he took formal charge, as people close to him say. Ever since his appointment as a director on the board of Tata Sons in 2006, he had insider access to the deep workings of the group and its various firms. After he took over as chairman, he visited both Kalinganagar, where a massive new plant is coming up, and Jamshedpur, where capacities are being augmented, and had asked hard questions of senior executives.

Here’s the thing.

Tata Steel is 106 years old, the largest entity in the group, and it brings in $26 billion in revenues. The century-old factory in Jamshedpur is a cash cow. Production capacities there will have touched 10 million tonnes by the time you read this story. On paper, this holds the potential to ramp up sales by 1 million tonnes towards the end of financial year 2013 and deliver $250 million in operational profitability. And its cost of production is the lowest in the world.

At Kalinganagar, in Odisha, steel will start rolling out of Phase I by October 2014. This phase will add 3 million tonnes to Tata Steel’s capacity. Two years down the line, it will double. In short, the company’s Indian operations hold the potential to manufacture 16 million tonnes of steel.

Which is small change when you look at what might have been.

You see, once upon a time Tata Steel had ambitions to create a behemoth that would produce up to 100 million tonnes of steel each year. That was one of the reasons why Ratan Tata had paid $13 billion to acquire the UK-based Corus, which is now Tata Steel Europe (TSE). Until date, it remains the largest acquisition by any Indian company.

The European Offensive

Corus was created when British Steel merged with a Dutch company called Hoogovens in the late 1980s. But, as Uday Chaturvedi, a Tata steel veteran who had a stint as MD of Corus Strip Products (CSP), a unit of Tata Steel Europe, says, “They practically functioned as two companies and even competed for the same orders until recently.” Not just that, Chaturvedi recalls how the Dutch unit received investments and specialised in producing steel that catered to the growing automobile manufacturing business in Europe. British Steel’s units in the UK, however, remained starved for investments because its primary customers—those in the construction business—were simply not growing.

And because the steel business was nationalised in the UK in the late ’60s, “the organisational structure had become bloated and bureaucratic”, says Michael Leahy, general secretary of the British Trade Union Community.

Other problems existed that undermined the company’s competitiveness. According to Chaturvedi, “A robust supply chain management is needed to cut costs, improving lead time with customers, to have correct working capital and making sure there are no stock-out.” But that hadn’t happened either. As a result, Corus kept falling behind its rivals.

These issues weren’t obvious when Tata Steel acquired Corus that was the time the UK company was riding a steel boom fuelled by demand from China. Because the going was good, the Indian management thought it wise to adopt a ‘soft hand’ approach on integrating the Indian and European operations. In hindsight, that was a bad move. Malay Mukherjee, a former director at ArcelorMittal, the world’s largest steel maker, says, “It is crucial you start integrating within six months of an acquisition. Else it gets too late.” He says his earlier boss, Lakshmi Mittal, who created a steel empire buying and turning around assets, would always have a post-acquisition team ready.

“It was a bad start,” says Leahy. And he blames Kirby Adams. (Adams, once MD of BlueScope Steel, was chosen by B Muthuraman, then MD of Tata Steel, to replace Philippe Varin, who was exiting Corus after seeing off the acquisition.) “We had a fraught relationship with Adams,” says Leahy. “He didn’t understand how to deal with unions. It was an unmitigated disaster.” Not surprisingly, Adams left in 2010. Even as all of this was happening, a slowdown started to loom and job cuts were rising.

At Corus, more than a year had passed before Uday Chaturvedi and T Mukherjee (who had just retired as joint managing director of Tata Steel) were sent to the UK, Chaturvedi to turn around CSP, and Mukherjee as an advisor. Mukherjee came back within a year. He was completely disheartened that none of his recommendations were taken seriously by the senior executives at Corus.

Chaturvedi initiated a dialogue with politicians and local communities, and put together long-term partnerships with customers, such as automaker Nissan. Under his leadership, CSP had started generating operational profits of $400 million by 2011. Carwyn Jones, a First Minister in the Welsh government, called Chaturvedi’s leadership at CSP “inspirational”. Similar initiatives needed to be replicated in the rest of the units.

But Chaturvedi’s stint was short-lived. Karl-Ulrich Köhler, a steel veteran from the German ThyssenKrupp, was chosen by the management in India to replace Kirby Adams. And Chaturvedi was moved from CSP and made Chief Technical Officer for Tata Steel Europe, under Köhler’s leadership. “I felt constrained and had no elbow room to take decisions,” he says. He eventually sought retirement in January 2012.

Köhler, the third managing director in two years, shifted gears in the restructuring process that Adams had initiated in Europe. He centralised functions across verticals and regions. His aim was to integrate key functions like operations, sales, marketing and the supply chain.

While the intentions were noble, the organisation was completely unprepared. Instead of improving communication channels with the leadership team across units, insiders said Köhler surrounded himself with ‘yes men’. An executive from Tata Steel Europe, who declined to be named, said Köhler surrounded himself with former colleagues from ThyssenKrupp: “There is no British executive in the top management.”

Throwing more light on the problem, Chaturvedi says, “Culturally, Tata Steel Europe is very diverse. You need to have someone at the top who understands the cultural differences, as the company’s operations are spread across Europe.”

To get around the problems, $80 million was spent to call in consulting firms, of which $30 million went to the Boston Consulting Group alone. But, says a former executive, “The consultants left when it was time to deliver.”

Corus, as a result, has a long way to go before it begins earning its keep the nearly $5 billion loan taken to finance the acquisition has now ballooned to close to $8 billion. Worse, it needs an operational profitability of about $1 billion to cover its interest and capital expenditure alone. Instead, production is down 30 percent and it has slipped into the red in the third quarter of this financial year.

When he joined, Köhler is said to have promised Ratan Tata that he would turn around European operations in three years. That time is up. In the UK, the word is that a search for Köhler’s replacement is on. And not a moment too soon: There are raging fires across the European business to quench, even as things in India are not quite on course.

The Battle of Kalinga

Tata Steel’s ambitious $7 billion greenfield plant in Kalinganagar is currently the largest industrial project in India. When done, it will have India’s largest blast furnace.

The new plant, which will produce flat steel to be used mostly by the automobile sector, is important for the company. “It is imperative we grow with our customers,” says TV Narendran, vice president of the flat products business. “Right now we are not able to meet their demand.”

Increased volumes at the new plant will add muscle to Tata Steel’s product mix. It will allow the company to produce steel that is wider, thicker, with higher tensile strength. This opens a potential window to get into new sectors like oil and gas, even as it improves what it can offer auto clients. “For example, right now we don’t make roofs for Toyota’s Innova. Once Odisha comes on stream, we will be able to,” says HM Nerurkar, MD, Tata Steel.

It ought to have gone live in February. But it is horribly behind schedule and has overshot budgets by almost $2 billion.

This situation, coupled with India’s ongoing troubles with Europe, has had a telling effect on the Tata Steel share price at the Bombay Stock Exchange: The scrip has plunged more than 60 percent below its 2007 high (the benchmark Sensex has risen by 15 percent over the same period).

And late entrants into the steel business, like JSW Steel and Essar Steel, are nipping at Tata’s heels.

Cyrus Mistry knows this. He fears that delays and cost overruns might rob Tata Steel of its advantages. Late last year, Mistry was in Jamshedpur addressing senior executives of the company. He was blunt: “You guys have won all the top awards in the steel sector. But how is it that you can’t execute your project on time?” Inside Bombay House, Mistry is said to have asked probing questions in meetings on the progress of the project. Often, the level of detail that he has sought has left most of the existing leaders stumped. “It was a subtle way of telling the top team that they didn’t have enough of a pulse on the company’s most critical project,” says an insider.

That explains why almost 30,000 people, including hundreds of officers from Tata Steel, are doing their damndest best to meet the October 2014 deadline. A stream of vehicles and men crosses the gates. Cranes, some of them more than 100 metres high, dot the skyline, along with fast mushrooming chimneys. Workers all over the site are busy welding.

Insiders say that the sense of urgency is now palpable. After all, that’s pretty much the only viable solution left: Add new capacities in a growing market like India in the hope that it will chivvy up profitability, and help lift the company out of the morass it finds itself in Europe.

“If the rate of performance between April and September 2012 was average, since then it has doubled,” says Anand Sen, vice president, Kalinganagar steel project. Since his deputation to Odisha from Jamshedpur last year, Sen has been the point man to ensure the biggest industrial project in India is completed on time. Sen replaced Hridayeshwar Jha, who was deputed to a group company, the loss-making Tayo Rolls.The heightened pressure has meant that Sen now has as many people as he needs to get the project in place. HM Nerurkar’s Principal Executive Officer, Arun Misra, has been sent to the site as deputy vice president to manage operations. Another veteran, Rajesh Ranjan Jha, was also appointed as deputy vice president reporting to Sen.

Unlike the South Korean steel maker Posco, which is still struggling to acquire land for its project, Tata Steel managed a volatile situation well after police firing killed at least 13 tribals. They were protesting against a boundary wall being constructed on the site and demanding additional compensation for the land Tata Steel was taking over. As with other greenfield projects across the country, the challenges—especially that of building ‘social infrastructure’ nature—have been immense for Tata Steel, consuming resources and time.

At the same time, the complacency was apparent. A person close to the top team told us on conditions of anonymity, “The company took some things for granted, not realising that infrastructure at Kalinganagar was non-existent, unlike in Jamshedpur where it was implementing the expansion programme. This led to delays.” When asked if the team to implement the project could have come in earlier, Sen simply replied, “Yes.”

The War Zone

Strategically, the new plant at Kalinganagar will mean a shift in the company’s internal balance. “By 2015, we would have 13 million tonnes of annual capacity in India. This will increase to 16 [when the second phase at Kalinganagar is commissioned] in another two years. That will make Indian operations bigger than the European. We will be a robust structure,” says Koushik Chatterjee, Tata Steel’s Group Chief Financial Officer. This hope, though, is on the back of some assumptions.

The chairman clearly knows that the performance here in Kalinganagar will have implications on the operations in Europe as well, which is now on life support. Mistry’s mandate is a clear one: Restructure the organisation, turn around the business and become financially viable. A consultant has been appointed to sell some of the assets in Europe and there is an increased focus on improvement programmes.

Chatterjee believes operations are turning around in the continent. “Benefits from the improvement programme may not be visible right now due to adverse economic conditions. But in another two years, Tata Steel Europe would be in a much better condition,” he says.

Be that as it may, Cyrus Mistry is effecting another change. Until now, only the finance team operated out of Bombay House. Everything else was headquartered in Jamshedpur. “It is strange that though 70 percent of its output and revenue was coming from Europe, the top management at Tata Steel have chosen to focus on India,” says Chaturvedi.

With a new Jamshedpur being created in Kalinganagar, Tata Steel will soon have two big manufacturing locations in India, plus overseas units in Europe and South East Asia.

Soon, a new distributed leadership team will take shape. Jamshedpur will no longer be the pivot around which the company operates.

And there’s one more factor.

The New General

Koushik Chatterjee looks like being the person who will lead the offensive. By all indications, he will take over at the helm at Tata Steel well before HM Nerurkar steps down as managing director later this year in September.

This may come as a shocker to most people who have followed the Tata group. Historically, the managing director of Tata Steel was chosen from a bunch of insiders who had risen through the ranks and learned the art of steel-making inside its huge blast furnaces: Russi Mody, JJ Irani, B Muthuraman and Nerurkar himself. Koushik Chatterjee doesn’t fit that mould.

He is 44, the same age as Cyrus Mistry. He trained as a chartered accountant, grew remarkably fast, and at age 34 was named the company’s CFO.

Soft-spoken and polite, he has been the face of Tata Steel for a little over six years now. As group CFO, he is perhaps the only person in the company who has the pulse of all of Tata Steel’s operations, both in India and overseas. Uday Chaturvedi says, “Koushik is great with numbers. He can take one look at the balance sheet and will know the impact. But it needs operations experience to know the cause. He will need support from the operations team.”

Chatterjee’s accession is unlikely to go down well inside the corridors of power in Jamshedpur, from where manufacturing bosses have preferred to rule.

This is something Mistry understands as well. To provide the cover that Koushik Chatterjee will need, Mistry is putting together a new leadership structure at Tata Steel.

The change is sure to shake up the system. Mistry realises this will have to be handled delicately. He has already initiated the building of a larger corporate office for Tata Steel inside the Forbes building at Fort in south Mumbai. That means, for the first time in its history, Tata Steel’s managing director may work out of Mumbai. And of course, the gentleman may not be an “operations person”.

Even before Chatterjee steps into the big job, insiders say that Mistry is already relying heavily on him to keep an eagle eye on investments, find the right leadership team to back, and also to quicken the pace of execution at Kalinganagar.

The Commander-in-Chief

Can Mistry hammer things back into shape? On the face of it, yes. Since the time he assumed charge, he has shown the patience to understand the situation on the ground—and get into the details—and trust his intuition to back the right set of leaders.

You must also remember that he grew his father’s business, Shapoorji Pallonji & Company, 10 times in a decade, and has a solid reputation for timeliness and fiscal discipline. To that extent, the assumption that this man is an untested entity may be an unfounded one.

At the March 3 function in Jamshedpur, Mistry wasn’t dressed in a formal suit as would be expected of the chairman of a large conglomerate. Instead, it was in a regular shirt with sleeves rolled up. It suggested a man willing to get his hands dirty by getting down to nuts and bolts and aware that he is in control.

With his predecessor Ratan Tata and the Tata Steel leadership team looking on, Mistry began to speak. “It is a time when we should reflect on values and entrepreneurial skills of our founder and reaffirm to those values which have helped in binding our group together.”

The Russian Roulette

Cyrus Mistry may have been a surprise choice for the top job at Tata Sons. Now it is time for him to spring a surprise at Tata Steel

About two months ago, Ardeshir Jehangir was in for a surprise. Tata group chairman Cyrus Mistry wanted to know if he’d be interested in the top job at Tata Steel. Jehangir had spent almost two decades at Tata Steel, serving many roles, including as former Managing Director JJ Irani’s principal executive officer. He left shortly after Irani’s retirement, citing “serious differences with the leadership”, moving to roles at Tata Quality Management Services and Tata Teleservices, before quitting the group. He would have been an ideal candidate for the job. He knew the dynamics of the steel industry, had unquestionable ethics, understood the Tata group values and was apolitical.

As it turned out, Jehangir didn’t want the job. He wasn’t comfortable with the current dispensation at Tata Steel, where he would have to work side-by-side with vice chairman B Muthuraman for at least one more year, when he would retire from the board. Muthuraman declined to speak. Besides, Jehangir was related to Mistry through a marriage between the two families and that didn’t make him comfortable in accepting the position. (He denied being approached by Mistry and declined to comment.)

Jehangir’s exit marks yet another twist to the ongoing drama surrounding Mistry’s search for a candidate to head Tata Steel. For the better part of last year, it was widely believed that Partha Sengupta, VP, raw material security, was the front-runner. It may well have been true, given that he had the support of Muthuraman. Sengupta had served as Muthuraman’s principal executive officer from 2005. His resourcefulness served him in good stead even after HM Nerurkar took over as MD in 2009.

But Sengupta’s hopes came crashing down on February 8 this year, when The Indian Express front-paged a story where his name was linked to the AgustaWestland controversy. Italian investigators probing the money trail in the VVIP chopper deal kickbacks discovered his name cropping up in the course of the conversation between one of the key accused middlemen and AgustaWestland officials, where they were discussing their line of defence before the prosecutors. Both Sengupta and Tatas denied their involvement and the story died down. A month later, news broke that CBI had interrogated Sengupta for his involvement in connection with the iron ore mining contract given to the company by former Jharkhand Chief Minister Madhu Koda. It was alleged that Koda and his associates took huge bribes to award contracts to various business houses, including Tata Steel, for giving iron ore and coal mining contracts. Although Tata Steel denied the allegations, it was unlikely that the board would ratify Sengupta’s candidature. Sengupta declined to speak for the story.

Now, Mistry is in a quandary. Whom does he pick? The only person who enjoys the complete confidence of Bombay House is Koushik Chatterjee. Tata Sons director Ishaat Hussain is known to be close to Chatterjee. When Mistry was on his fact-finding mission in February this year, it was Hussain and Chatterjee who were by his side at Kalinganagar.

However, in a manufacturing driven culture, Chatterjee may not be quite the right fit. As things stand, Chatterjee will have two presidents reporting to him, Anand Sen from Kalinganagar and TV Narendran from Jamshedpur. Together, the new team will be vested with the responsibility of restoring Tata Steel’s preeminence as a company with values and the highest ethical standards. How well they fare could determine the course of Mistry’s tenure at Bombay House.

First Published: Apr 15, 2013, 06:22

Subscribe Now