Nissan's Indian Gamble with Datsun

The resurrection of Datsun, a brand dead for 27 years, is key to Nissan's revival in India and three other markets. Will the bet pay off?

The Japanese have a word that every salaried person in the country understands. Nomikai. Nomi means drinking and kai means partying. On May 15 this year, 17 members of a team from Nissan Motor Company in Yokohama decided they deserved a nomikai. Reason: Almost four years after the 2,67,000-employee-strong company decided that it would bring the Datsun brand back to life, Nissan okayed a manufacturing contract for the vehicle to be rolled out in Russia.

So what’s that got to do with us?

Everything. The nomikai in May has an umbilical link to Nissan’s plans for a bigger splash in India. On July 15, everybody who matters in Nissan Motor Company will be in New Delhi for the global unveiling of the Datsun by Carlos Ghosn, 59, chief executive officer of the Renault-Nissan Alliance.

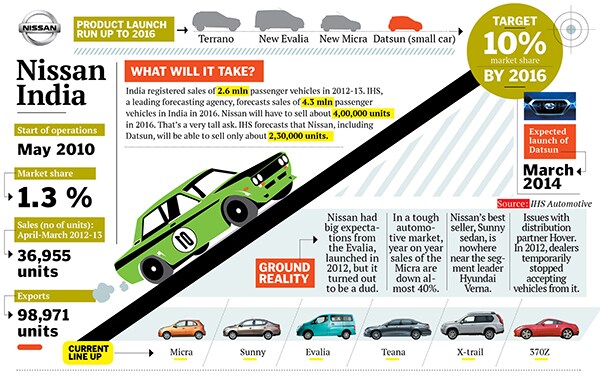

To make it big in fast-growing markets such as India, Russia, Indonesia and South Africa, Nissan decided that it has to gamble big. It decided to revive the Datsun brand, which it had killed deliberately in the mid-1980s, and create a car specifically for these markets, since the main Nissan repertoire hasn’t scored. (In India, Nissan’s market share is a micro dot—1.3 percent.)

Not since it created the Infiniti as a luxury car brand in the 1980s has Nissan done anything as big.

That’s why the Russian manufacturing contract is a big deal. It is a shift from tinkering with small sums to final commitment to big bucks. Take a moment to understand this: A manufacturer creating a concept car is risking $10 million. A detailed engineering of the vehicle, called profile, is like plonking $70-100 million on the table. But a contract which commits investment in a brick-and-mortar facility from where the vehicle will actually be rolled out is a risk that runs above $400 million. Not a small bet even for a $100 billion corporation.

Ghosn has been waiting for this day for close to four years. It is a critical part of his Power 88 strategy—88 stands for 8 percent global market share and 8 percent operating margin.

Ghosn told Forbes India: “Datsun has been the strength of Nissan and we aim to revive our strength to target 40 percent market share in emerging markets. It is a global brand and our priority will be to concentrate on India, Indonesia and Russia.” The car will be rolled out in all these markets in early 2014.

Ghosn has huge expectations from the Datsun brand in India. Nissan wants to increase its overall domestic market share to 10 percent by 2016—an eight-fold jump from the piffling 1.3 percent it has notched after three frustrating years in the Indian market. Ghosn is hoping that 40 percent of this 10 percent market share will come from Datsun.

Says Ghosn: “Datsun is something which has been prepared within the Nissan Power 88 plan, making sure that people in high growth markets have an attractive offering from our company. With the aim of sustainable mobility and mobility for all people, Datsun will offer modern and comfortable products with good quality, which are reliable, generous and desirable.”

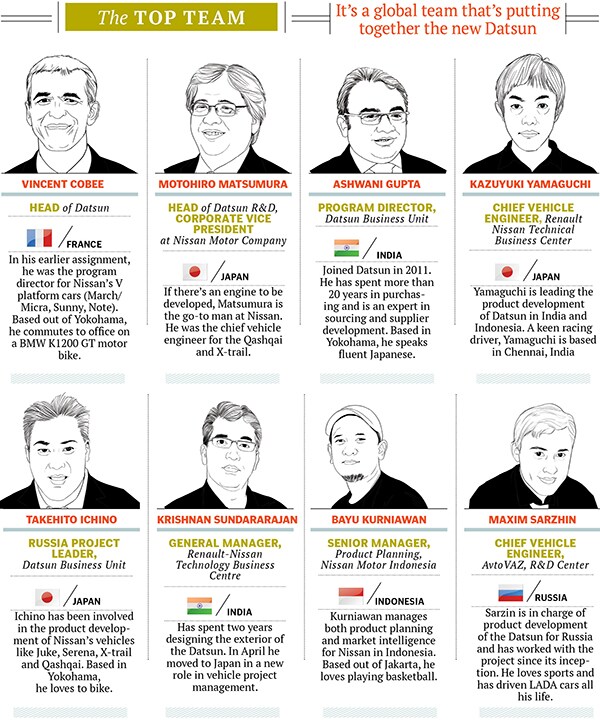

The man on whom Ghosn’s hopes are riding is Vincent Cobee, 45, global head of the Datsun project. Cobee explains Datsun’s nomikai moment thus: “It is not easy to carry a project which has no revenue as of now, and which is poorly understood by the average Nissan employee, because it is different from what we [the company] have done before so you need to get people together and you need to celebrate.”

A Frenchman who has spent the last 11 years of his career in Japan, Cobee has other reasons for quaffing the stuff with the other 16. When you are a part of a project the size and significance of Datsun (of which more later), your life is office and your colleagues are your life. A nomikai is a good reason to leave early, tear down the formal structures of a Japanese corporation and let off some steam in a free wheeling, open discussion.

The 17 executives did just that on that evening last May. They went to a traditional Yakitori restaurant near Hon-Atsugi station and finished just before the last train home.

It will be fair to say that Nissan India is running on steroids right now. The 500-odd engineers at Renault-Nissan Technology Business Centre, located south of Chennai, are rushing against time to put together the final touches to the Datsun they will unveil before their boss in July.

Employees at Nissan’s distribution partner in India, Hover Automotive, are also working unusually late hours to finalise the standard operating procedures for customer handling at dealerships. The idea of a separate dealer network in addition to Hover is being tossed around. A new vice-president, Ajay Raghuvanshi, has been poached from Hyundai India and is evaluating this idea’s potential. Another team at Hover is busy working out the details of the ‘shop in shop’ model through which the Datsun will be sold at existing dealerships. The dress code of Datsun’s sales staff, which will be different from that of people selling other Nissan cars (Micra, Sunny, et al), is under review. Terms and conditions of new dealerships (1,500 sq ft and four bays of workshop area compared to 3,000 sq ft and 10 bays in the past) are being given the final touches to invite applicants.

Given the potential size of the sub-Rs 4,00,000 car market, Nissan wants to grow its dealerships more than three-fold, from 97 right now to about 350 by 2016.

Early in June, a new Micra, currently Nissan’s entry model for India, was launched to yield space for the Datsun. The new Micra has more bells and whistles than the previous iteration and will be priced a bit higher than the current Rs 4,30,000 model (ex-showroom, New Delhi). This is being done with a single purpose in mind: The Datsun (priced under Rs 4,00,000) is going to be the new entry-level car in India. The Micra must stay clear to avoid any confusion and product cannibalisation.

Nissan has never attempted anything like this before. With the Datsun, Nissan wants to crack the heart of the market in four high-growth economies where today it does not have any product—the low-end of the market is 50 percent of the total in India, 40 percent in Indonesia, 30 percent in Russia. “It is by far the biggest endeavour Nissan Motor Company has had since the launch of Infiniti in the ’80s,” says Cobee. But the Infiniti was targeted mostly at the North American market while the Datsun is spread across four geographies. “In terms of magnitude of business engagement, the only thing that comes close to this is the decision in the early ’60s by Nissan to go abroad,” he adds.

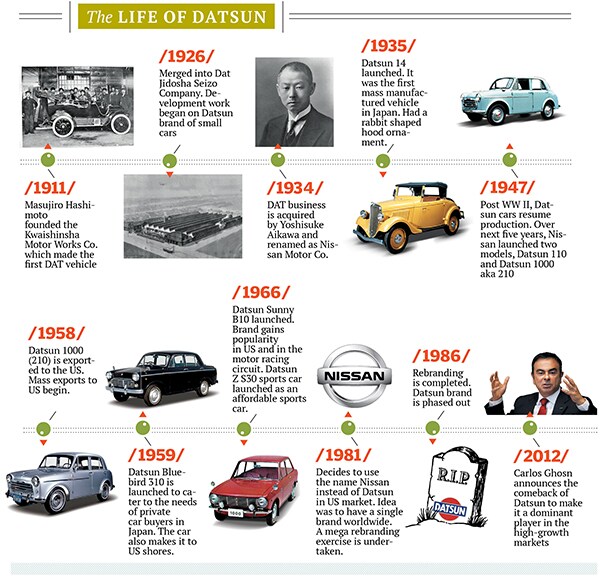

To understand why Nissan executives are pacing the floor like future dads outside a maternity ward, consider the following facts: Datsun was the first brand under which Nissan started selling cars way back in 1933. That’s 80 years ago. It was with the Datsun name that Nissan sold cars in more than 180 countries and for over 50 years. A vast majority of Nissan’s executives entered the company in the last years of Datsun. The brand was phased out in March 1986—that’s 27 years of brand rigor mortis. And now, it is being brought back from the dead.

Why would any company want to revive something it consciously decided to dump?In early 2009, Ghosn was staring at a cruel reality. Thanks to the economic downturn, Nissan was having a tough time in the traditional high-growth automotive markets of Europe and North America. But in the markets which were poised for a take off—the likes of India, Russia, Indonesia and China—Nissan had been a late entrant.

Cobee says, “You can sub-divide this realisation. One is that the auto market will grow in places where we are not perfectly geared as of now. Two, the demand of those markets is specific. Nissan, which is a global brand with global products, is not, and has not, managed to be a mainstream entrant to [cater to] this demand. It is a valuable offer for experienced, repeat customers in the developed markets but it is not, and cannot be, the mainstream answer to this emerging middle class demand.”

Clearly, Ghosn needed a new strategy. His goal is to sell cars to everybody and he has been chasing it with several ideas—an ultra-low-cost car or a small car that’s value for money, reliable and modern. Not one car, but something that had the potential to create a whole category of vehicles. Like what Kia is to Hyundai or Skoda to Volkswagen.

That’s where the idea to bring back Datsun was born. In November 2009, the plan was frozen.

In December 2009, Cobee was asked to lead the project. At that time, he was the programme director of the entry-range of Nissan cars, and it was his job to launch the Micra and Sunny in India, Indonesia, Mexico and China. He had been working on it for almost three years and the company was just gearing up to launch. It was then—before he had sold even a single unit—that he was asked to take up Datsun.

Ghosn’s expectation from Datsun was simple—bring an attractive, modern offer to the high-growth markets by 2014. The only rider: The project should be NPV (net present value) positive. In other words, you pay back what you invest.

Cobee, on his part, wanted Ghosn’s agreement on something else—Nissan had to be ready to make some tough decisions and he should get a free hand to pick his team. “In any new venture you need to be ready because it might not work. This is not a business-as-usual evolution of the Nissan brand. This is venture capitalism within a large company,” adds Cobee.

This was certainly a big promotion for him. A programme director’s job is limited to building a line-up of vehicles. As head of Datsun though, Cobee would have to lead everything—manufacturing, brand building, sales and distribution strategy. No amount of in-house training can get you ready for the role. Cobee too found the transition difficult, especially in a Japanese corporate culture where transitions happen at lightning speed. “The transition from an ongoing, high activity programme director’s job to ‘let’s re-launch Datsun’ was a total cliff,” he says.

Cobee says it took this team three months just to understand the opportunity and challenge before them. “You start by saying okay, Datsun, high growth markets, strong demand, but that is a very think-tank approach. When you put it on paper, you say we could launch it in three markets in three years and we could sell 100,000x cars in a short timeframe. Then it becomes a very different type of game,” he says. That’s when the questions start popping up—what is the styling identity, what is the brand logo, how do you distribute the cars, where do you manufacture them, where do you develop them, where are your suppliers, which media mix will you utilise? That’s when reality starts sinking in. “So you move from the phone-is-not-ringing [phase] to [the point where] you have a hard time sleeping,” adds Cobee.

A critical part of any project is building a team that can deliver. Cobee went about it with two parameters in mind. One is that the team had to be absolutely lean. So at headquarters in Yokohama, he has only 17 people working in Datsun. Globally, the strength of the Datsun corporate team is just shy of 50. Add to that number the 500 engineers working on the product in India and 150 engineers in Russia and that’s it. Automotive experts agree that this is a very lean number. Wilfried Aulbur, a former boss at Mercedes India and currently managing partner & CEO at Roland Berger Strategy Consultants, says that this shows Nissan is keeping a strong check on costs. You shouldn’t build a car for the emerging markets with development costs of first world countries, he says.

Cobee says the whole project is in a sort of venture capital mode: “You don’t spend truckloads of money until you have proven your case. You don’t build a team ahead of the results. Purposefully, the size of the team is behind workload and results. Two, if you want to do it quick and right, you need people to communicate with each other, you need to know what the other is doing.”

Cobee added other criteria for his team—he didn’t want any average performers! This is a lesson he learnt during his days at university. People will make the difference. “You can’t deal with average performance when you are bringing up a very massive, transformational subject as part of the launch company,” he adds.

That’s how he picked Ashwani Gupta, 43. Cobee doesn’t pretend that he understands deeply the needs of a customer in India or in Indonesia or Russia. “It is written on my face and my passport that I didn’t grow up in a country where economic growth was a miracle. I grew up in a country where economic recession is the new mantra,” he says. So he picked a person who did grow up in an emerging market economy. Gupta was hired from Renault as the programme director for the Datsun business unit. Before he joined Datsun, Gupta, based in Paris, was part of the team that took care of purchasing functions at the Renault-Nissan Alliance. His stint at headquarters was preceded by his role as head of purchasing at Renault India.

If Cobee is the guy with the smarts, style and strategy, Gupta is the man in charge of getting the project off the ground with local teams across the globe. Managing a cross-cultural team—Indians, Indonesians, Russians, French, Japanese, Chinese and South African—is anything but easy. Last year Gupta was travelling for 152 days. That’s because the action is in Chennai (India), Jakarta (Indonesia) and Togliatti (Russia).

Gupta himself displays a strong distaste for the word ‘localisation’. He says it gives a feeling that a product has been done somewhere by somebody for someone and then imported into the market. That’s not how the Datsun is being built. “For us local means originated, thought, developed and delivered by the people who are located in a particular market,” he says. This is important because often large multinational companies sitting in global headquarters are far removed from ground realities.

“A person sitting in Yokohama headquarters, how will he know what will be the impact of the product in the local market? The right guy is the guy who has been born and brought up in that region,” says Gupta. And it is this local perspective that translates into understanding what the customer really wants in the car.

Nissan calls its customer in India as ‘up and coming’. Gupta says, “To buy a car is a celebration. These are the customers who name the car with a pet name. They want to be recognised as successful or on the path of being successful in society.” Also, in India, customers are extremely picky and driven by astute economic rationale. Nissan has estimated that its target customer is going to spend more than two years of his/her disposable income on buying a Datsun.

Gupta says he knows that at Rs 4,00,000 the Datsun will be an entry-level vehicle for Nissan, but it is still not a cheap car for the customer. More importantly, it will certainly not be the only choice before her. For decades now, this customer has exercised choice by buying cars from a single company, Maruti Suzuki.

As things stand, Maruti Suzuki has a more than 80 percent share of the market in which Nissan wants to play with the Datsun. Even the might of Hyundai, the second largest car company in India, met with average success when the company attacked Maruti’s territory with the Eon. Hyundai had everything going for it, a car that looked different from Maruti’s vehicles (the 800, Alto, A-Star and Wagon R), better features in terms of safety and entertainment and competitive fuel economy, but it quickly moved from being the Alto beater to just another car. Add to this the fact that Maruti’s distribution extends to about 1,350 cities in the country, which is almost 12 times more than what Nissan has today.

Aulbur says Nissan must get four things right: “You have to get the product right. Does the target group see it as an opportunity to make a statement? Then you have to get the pricing right, without it sounding like a cheap product. Third is distribution, you should have the same level of density [penetration of dealerships in a city] as your nearest competitor. Last, you have to get all of it right the first time.”

Cobee says he knows about the 1,000-pound gorilla in India. And then he gets a bit carried away. “Or is it an Indian company which also sells cars in Japan?” he asks airily.

The key question is: Does Maruti Suzuki have any chinks in its armour that Nissan can exploit? Gupta says Datsun will focus on aspirational first-time buyers. He says there are two choices before this customer today. One is that he can buy a used car but that will be looked down upon in society. The second is a label in the market with antiquated technology on an antiquated platform. “This means it was made for someone by someone, somewhere and I have only this option. Is this offer going to be differentiated in price offering? Maybe yes. Will it be a differentiator for the happiness I am looking for? The answer is no. The answer we believe is durability, attractiveness and trust. And modern styling with the latest technology,” he adds.

What if this doesn’t work? Is there a Plan B? “No I am not working for Plan Bs,” says Cobee. “When you are a sportsman, you don’t play a tennis game or run a track with Plan B in mind. You play it with the intention to win.”

Quite. But this is more than just a game. Datsun will be the biggest test-bed for Ghosn’s Power 88 plan. Aulbur says that by the looks of it Ghosn has taken the right call by bringing back the Datsun. A global brand like Nissan has limitations, a sub-brand like Datsun has the potential to be a mass market offering. “But execution has to be right. Attention to detail makes or breaks an auto company,” he says.

Cobee knows that Maruti Suzuki is no pushover and he also understands the risks. “To me the risk is in the details,” he says. The car is ready, but he now has to approach each market with the right amount of local knowledge. “We need to combine official communication with references need to give the customer an opportunity to meet and experience the product need to be extremely precise, transparent and reliable on the connected services from maintenance to finance to accessories to overall repair activities. I have the formula. Question is how do you cook the formula correctly?” he asks.

For a start, you cook it by figuring out what the customer wants. Maybe, just maybe, he has learnt enough about the Indian customer to make the Datsun earn a place in the Indian sun.

First Published: Jul 08, 2013, 06:29

Subscribe Now