Narendra Modi: Role Model of Governance?

Gujarat's growth story is an expression of the chief minister's authoritarian power

Early in August this year, I called somebody I know advises Narendra Modi, the powerful chief minister of Gujarat. Is there really any merit, I asked him, in all the fawning over Modi? “Yes,” the advisor replied without hesitation. “I’ve seen the man in action. He is a visionary. Go to Gujarat and see. He has cleaned up the administration. Investments are flowing. He is transforming the state.”

My question had its roots in a now-familiar narrative. It begins from the glowing testimonials. “Modi’s leadership is exemplary, Gujarat will provide leadership beyond country,” India’s most respected tycoon Ratan Tata is quoted on the website of the Gujarat government’s flagship event, the Vibrant Gujarat Summit. Media magnate and chairman of the Zee Group Subhash Chandra considers Modi as the person who “redefined politics, performance and principles”.

In my mind, like in that of many Indians, Narendra Modi is inexplicably linked to February 2002 when mobs murdered, raped and burnt hundreds of Muslims, including women and children, in an inhuman orgy of violence on his watch. Then there are hazy memories from 10 years ago of the state’s commercial capital Ahmedabad. In memory it was a messy city, like many others—chaotic, polluted and emblematic of all things wrong with urbanisation in India.

But journalism is the kind of business that demands you trust nothing but your eyes. So a month later, I was in Ahmedabad. Without doubt, it looked like one of the better managed cities in the country. The roads were wider and public spaces greener than I remembered. An efficient Bus Rapid Transit System connects the eastern end of the city to the western corner. Another one connecting the other two poles is under construction.

The Sabarmati river, which runs through the city, used to be dry and surrounded by slums. Instead, fed by Narmada waters, it was in full flow between the newly-built 10-km-long promenades on either side.

I could see the city was growing with a 76-km-long ring road encircling it. That road was conceived and built in record time and with minimum fuss under Surendra Patel. He used to be chairman of the Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority (AUDA), which supervised the project. In his office where I met him, a detailed plan of how the riverfront would look like was pinned on a soft board. “I still follow up on the project,” he says. “It started during my time.”

Over the next one hour, he talked passionately about Ahmedabad of how he transformed AUDA from a small office with a few people and barely any revenues into a modern city developer and of how land was acquired for development. AUDA first got the Town Planning Act amended to notionally acquire all the land and regularise their uneven dimensions into geometrically even shapes. Then he told the landowners of a plan he had in mind.

AUDA would take over half their land. A fifth of AUDA’s share would go into building roads and the rest developed for commerce, residence and parks. He told them that once the project was complete, the other half of the land they would continue to own would be significantly more valuable than all of their land put together. “My promises weren’t empty ones. I used to take contractors with me to show them we meant business,” he says. And he delivered.

By then, it was obvious Patel’s heart was in urban development and he had a knack for it. It was inevitable then that I asked him why he quit AUDA for the Rajya Sabha in 2005. “Because Narendrabhai asked me to,” he said in a matter-of-fact tone. “I told him my heart was here. But he insisted I go. I cannot say no to him.”

This was strange. Here was a man who was good at what he did he was liked by the locals and was a respected leader of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Why, then, would Modi insist he leave? I called Jagdish Thakkar, Modi’s public relations officer, for a meeting with the chief minister. “Send me an email with probable questions and I will get back to you,” he said. Thakkar never responded to my email and remained elusive on the phone.

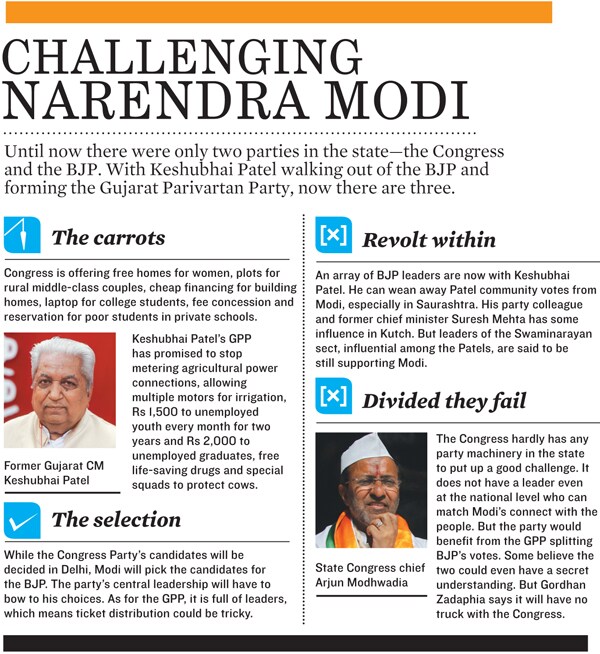

There were other things on my mind as well. For instance, the clamour of voices asking Modi be crowned prime minister is mounting. Modi has so far maintained a stoic silence on the subject. But to an observer from the outside, every action of his indicates he is manoeuvering himself to a point where ignoring him for the job would be difficult. His ambition will be put to the test in December when Gujarat holds elections. Modi wants to capture 150 seats, up from the current 122 in the state Assembly of 182, to seal his reputation as one of India’s most popular political leaders.

That said, the ghost of 2002 continues to loom.

On August 29, I was scheduled to meet a BJP MLA and former minister in the Vidhan Bhavan, the seat of the Assembly. I ran into the legislator in the parking lot itself. He looked tense. The chief minister had called an emergency meeting. “I cannot talk to you,” he said and walked away.

It wasn’t entirely unexpected. Even as I was getting there, a special court in Ahmedabad had delivered one of the rarest verdicts in the history of India. Special Judge Jyotsana Yagnik convicted Maya Kodnani, a former minister, and 31 others for rioting and murdering 97 Muslims, including a 20-day-old infant, in Ahmedabad’s suburb of Naroda Patiya on February 28, 2002. Modi’s government was bracing for the fallout of the verdict. Nobody knew what the repercussions would be. Cases are still pending and the heat could singe even Modi.

As we drove out of the complex, a colleague who was accompanying me pointed to a building under construction. “That is the new office of the chief minister. Modi has instructed Larsen & Toubro [the contractor] to finish it by December. Work is on day and night. He wants to occupy that office when he returns as chief minister four months from now. He knows he will win again,’’ he said.

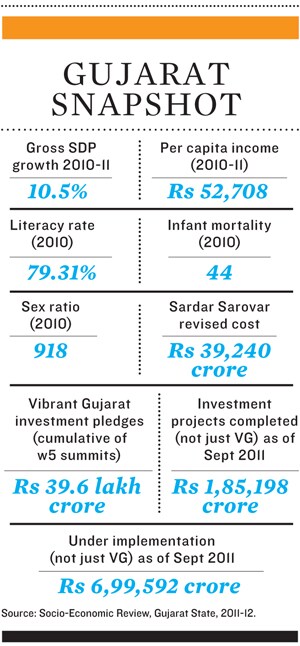

I suspect Modi’s confidence that he will return to power stems from the outcomes of what he calls the “Gujarat model of development”. Under him, industry in the state has grown in double digits. More children are now in school than ever before and agricultural growth is several times the national average. Modi told a farmers’ gathering recently that arable land in the state had increased by 37 lakh hectares. Land covered by micro-irrigation projects alone had increased from less than 1,000 acres to over seven lakh hectares in the decade of his rule.

The administration works with clock-work efficiency. Need a driving licence? Not a problem. Apply online. Appointments for tests and interviews are given promptly, much like they are for passports. Licences arrive by post with a personalised letter from Modi. Similar letters accompany documents that register a new vehicle in the state. These letters highlight the fact that, thanks to economic and industrial development in the state, the lifestyles of people have improved significantly. But, the letter urges recipients to use public transport to save fuel and reduce pollution and that when they do use their own cars, to observe traffic rules carefully.

Such personalised letters are just one of the many tools deployed by Modi’s public relations machinery. Radio and TV channels constantly air advertisements trumpeting his achievements. There are few streets in Ahmedabad or Gandhinagar that don’t have a hoarding with his picture on it—smiling benignly, at times in a traditional turban at other times business-like in stylish jackets and yet others in his trademark half-sleeved kurta, hands raised and index finger pointing upwards. Wherever you look, the leader is on extravagant display.

On September 3, I walked into Mahatma Mandir, a giant windowless concrete convention centre that Modi has had constructed to host large, attention-grabbing events. I was there to listen to him speak to farmers gathered at a global convention on agriculture technology. The cavernous hall was packed. About a thousand farmers were seated on chairs lined in perfect rows. Placards were placed at intervals that read Monsanto, GNFC, John Deere and United Phosphorous.

The massive flower-bedecked stage was flanked by two giant screens and huge batteries of loudspeakers. A few minutes later, a woman announced the arrival of the chief minister. Clad in a beige kurta-pajama, his white beard trimmed to perfection and every hair in place, Modi walked in from the back of the hall followed by a sizeable entourage of government officials and colleagues. His speech was stellar, and very personal. It was all about My Gujarat, My farmer, My Vibrant Gujarat. His connect with the audience was immediate.

Tentative appreciation gave way to resounding applause as Modi listed Gujarat’s achievements. “Agriculture in Gujarat has moved from rain-dependent to irrigated. It has moved from subsistence farming to cash-cropping,” he said, listing the steps he took to push up average decadal agricultural growth to 10 percent. He urged those in the audience to dream big—big enough to produce and feed all of Europe. He outlined plans to set up an agriculture university with Israeli help to award doctorates in farming and organise a global farm summit every three years in Gujarat.

And then he took aim at the Central government. “These initiatives should have been done by Delhi but I don’t know if they will be able to do it. I don’t know when they will be able to look at soil and farmers. They are mired in coal,” he said to resounding applause. In about 45 minutes, Modi positioned himself as the leader who thinks big—big enough to lead the country.

Outside the hall, I struck up conversations with farmers. “How did you hear about this programme?” I asked a couple of them who had come all the way from Nandurbar in Maharashtra. “We were brought here by GNFC,” one of them volunteered. “They paid all our expenses,’’ he said. That’s when the purpose of the placards dawned on me. They were enclosures marked for farmers sponsored by each company.

Choreographed events aside, people speak admiringly of Modi’s workaholic ways, of how he keeps a hawk-like vigil on everything and everyone, and the efficient e-governance systems he has put in place to stay in touch with ground realities across Gujarat. Yet, once upon a time, the state was far from his mind.

“He used to openly tell us they did not like him in Gujarat and he had no interest in going there,” a senior television journalist who has known him from the days when he was a regular standby at Delhi’s numerous studios, playing second fiddle to BJP’s national leaders such as Murli Manohar Joshi. “He once waited four hours in the ante room to the studio when Joshi was on a panel discussion just in case Joshi left midway and he got a chance to replace him on the panel,’’ the journalist remembers. What changed?

“He thinks and plans long-term. And he knows very well how to position himself,” says a person who is close to the BJP leadership and who has known Modi for a long time. Since he took over 11 years ago in Gujarat, Modi has managed to convert it into one of the better governed and most aggressively marketed states in the country.

At the 2011 Vibrant Gujarat Summit, the state’s now-famous investment biennale, he got businesses from across the world to sign nearly 8,000 MoUs committing $460 billion in investments. Tata Motors and General Motors already operate out of Gujarat. Ford Motors, Peugeot and Maruti are planning new plants. With so many auto and auto ancillary projects in the pipeline, Modi has gone on record saying he’s done with wooing automakers. He now wants to focus on defence equipment manufacturing, he told the Wall Street Journal recently.

About 12 kilometers from Ahmedabad, one of his most ambitious projects is taking shape. Called the Gujarat International Finance Tec-City or GIFT, it hopes to replace Mumbai as India’s financial services hub. On paper, the plan looks impressive. Spread out over four square kilometres, the city will have constructed spaces of 8.5 million square feet. Planned as an eco-friendly city, it is intended to have state-of-the-art communication, transport and living facilities. The financial city will complement another massive development at Dholera, an 800 square kilometre special investment region, two hours by road from Ahmedabad. It is one of the six planned mega investment regions and is intended to be a self-governed global centre for economic activities close to sea and air ports. Dholera is one of the developments along the 1,535-km Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor, 38 percent of which falls in Gujarat.

Even with the red carpet, there is palpable unease when you ask businesspeople in Gujarat for their views on Modi. They decline to come on record in spite of the fact that many of them have a positive opinion of his administration except a common gripe about corruption. “I can talk to you candidly only if you assure me you will not quote me anywhere,” the promoter of a Rs 1,000 crore Ahmedabad-based manufacturing company said when I called him. He told me that they still have to pay “speed money” to get things done. “Often, we get calls [from top government officials] asking us to sign MoUs. We ourselves have signed two, though I know that nothing will become of them,’’ he says.

On the day Maya Kodnani was convicted, I met Fr Cedric Prakash at a press meet called by his organisation Prashant, which had helped victims of the 2002 riots fight their battle for justice. I asked him if he feels threatened. He said he and his colleagues are watched. Each time there is a conference at their office, somebody from the state intelligence bureau keeps a watch on visitors.

Satish Mori, director (news) of VTV, a channel that focuses on agriculture, business and rural development, had a taste of government pressure this February. VTV ran a story on a budget proposal to remove value-added tax from items used in worship such as incense sticks and camphor chips.

The channel argued these items are sold at small establishments which rarely issue a bill and, therefore, it is practically impossible to impose VAT on them. The Modi-government immediately stopped all advertisements to the channel. Mori says things were sorted out only after he met the chief minister. Shreyans Shah, the 65-year-old managing editor and publisher of Gujarat Samachar, told me his paper has faced the same problem several times. “But I don’t care. Governments before this have also done it [stopped ads] to us. I am used to it.”

The image-conscious administration is primed to actively discourage any criticism of Modi. Two people told me that they were threatened directly by a former minister who is currently facing a criminal investigation. Another, Gordhan Zadaphia, a former colleague of Modi’s, says the chief minister had personally threatened him if he did not fall in line. Zadaphia left the party in 2007 to form his own outfit which he has now merged with 84-year-old BJP deserter Keshubhai Patel’s Gujarat Parivartan Party.

One by one, every senior leader in the Sangh Parivar has been made irrelevant. Keshubhai Patel, Zadaphia, Suresh Mehta, AK Patel, Kashiram Rana, the list goes on. VHP leader Pravin Togadia is a shadow of his old belligerent self and senior RSS leader Sanjay Joshi, known as much for his organisational skills as his rivalry with Modi, has been exiled to Delhi. So strong is Modi’s dislike for Joshi that he refused to attend the last BJP national executive meet in Mumbai if Joshi was present. The leadership finally bowed to Modi’s pressure and sidelined Joshi.

A person who has worked with a former minister in Modi’s cabinet spoke of how between 2002 and 2007 he created a back-up for party organisation. Modi appointed five gramsewaks in each of Gujarat’s 18,000 villages. These were local, educated youth, loyal to the crown. They have a say in local decision-making such as allocating funds, forming self-help groups and grading them for loan eligibility. They became key grassroots players and were a useful influence during elections. “Ministers hardly have a role in this government. It is run by bureaucrats. Even the ministers’ performance is evaluated by them,” the person says. Local administration offices are connected with high-speed internet and video-conferencing equipment. It helps senior officials sitting at the headquarters monitor progress of government projects at the ground level. It also doubles up as the backbone of Modi’s public relations machinery, says an official.

Government officials have another key role to play. Large gatherings such as Garib Kalyan Melas (fairs for the welfare of the poor) are managed by the collectors and choreographed to the minutest detail, including camera placements. Instructions are passed on through video conferencing. Broadband connections help in sending high-resolution pictures of Modi that are to be used on hoardings and posters. Jobs such as arranging buses that transport crowds to the venue, organising lunch packets for those attending and erecting pandals are farmed out to local officials. Senior district officials are later expected to send detailed reports of the event. A veteran journalist in Ahmedabad said that at a Garib Kalyan Mela in Banaskantha district some months ago, the chief minister had distributed cheques to the poor. Some of the envelopes turned out to be empty. Apparently, the officials were unable to process all the applications in time.

This unrelenting pressure is beginning to tell. Schoolteachers I met in a village say they are made to do data gathering work. A senior official told me a lot of his time is spent in organising melas. “Each employee is working on these melas at least 150 days in a year,” he says. Compounding their problem is the fact that the state has not recruited significant number of people in Grades 2 and 3 since 1987, except for posts that were urgent. In the next one year, about 40 percent of the current employees are expected to retire, the official said.

Modi came up with an ingenious way to economise on resources. The government hired people on fixed-pay contracts. Called Lok Rakshak for police constables, Vidya Sahayak for teachers and Vidyut Sahayak for electricity workers, they had five-year tenures after which they were eligible for permanent employment as freshers. They were paid as little as Rs 2,500 per month. Helpers in prisons and courts were paid just Rs 1,500 per month. There are about five lakh such employees.

An Ahmedabad-based human rights organisation, Yogkshem Foundation for Human Dignity, filed a PIL in the Gujarat High Court against this practice and the court, in an interim order, asked the government to raise the pay to a minimum of Rs 4,500 per month. “The government was enforcing minimum wages in the private sector but was flouting its own laws with impunity,” said lawyer and Yogkshem founder-president Rajendra Shukla. Last December, the High Court ruled that the policy was wrong and that the government should pay the difference in wages for all the years. Making up for this amount will cost the state exchequer at least Rs 10,000 crore. It has appealed in the Supreme Court where the case is pending.While it can be argued that all of these initiatives were put in place to fast track growth, Gujarat has fallen behind on some key development indices. Malnutrition among children, especially in the tribal belt of eastern Gujarat, is high. A high incidence of anaemia has been reported even among middle class women. Infant mortality rate in the state has dropped to 44 per thousand births from 48 five years ago. But it is much worse than other industrialised states like Tamil Nadu (24) and Maharashtra (30).

While Modi urges new car owners to use public transport as much as possible, during the years he has been chief minister, the fleet size of the Gujarat State Transport Corporation shrank from 10,048 to 7,621, of which only 6,327 are on the roads on an average day, according to the Socio-Economic Survey, Gujarat State, 2011-12.

Despite high industrial growth, the number of educated job-seekers registered with employment exchanges in the state rose by 16 percent in the last five years. Since 1995, the private sector has added only 5.6 lakh jobs while public sector jobs shrank from 9.7 lakh to 7.94 lakh in 2011. This means, net jobs created over 16 years was just about 24,000 each year. And in a state where women can fearlessly walk the streets unaccompanied even late in the night, the share of women workers in private sector jobs has stayed at 10 percent for 16 years, data from the survey show.

Modi has also been unable to complete Gujarat’s flagship development project, the Sardar Sarovar dam and irrigation project, which would have benefited about a million farmers. Less than a third of the distribution system is finished. “The dam was a priority but not the canals because the dam was visibly big and attractive,” Shreyans Shah of Gujarat Samachar says.

I asked YK Alagh, agricultural economist and the man who conceived the project down to the last mile delivery of water to about 1.8 million hectares for a million farmers, on what went wrong. “In the last decade, Gujarat’s agriculture grew fast. But to say it was 8-10 percent is incorrect,” he said. Alagh, who is now chairman of Institute of Rural Management (IRMA) and chancellor of Gujarat Central University, said, “Growth in dry land agriculture—and our irrigation coverage is still low—fluctuates, and two statistical sins are unforgivable. One is to take bad initial and good terminal years.” But agricultural growth in Gujarat is the highest in the country, perhaps even in the world. The real rate though may be close to six percent, he said.

There are other glaring incongruities on the ground. In Patan Assembly constituency, represented by Anandiben Patel, revenue minister and one of the few people close to Modi, farmers complain of discrimination. In spite of Jyotigram Yojana, a successful power management plan with a dedicated supply line for agriculture, farmers in Jamtha, a small village in the constituency with a voter population of 700, say they have not had power for two months, save two days. “We’ve been singled out,” sarpanch Shobhaji Jumaji says, “because the village votes for the Congress.’’ In the last election, only 18 voted for the BJP. He claims Patel has been openly saying things will get better only for those villages that vote for her.

Beneath the visible development in Gujarat, there is an undercurrent of authoritarian power. “People do not realise that democracy is at stake,’’ says Hemant Shah, professor of economics at HK College of Arts in Ahmedabad and a trenchant critic of Modi. Shah, who has published several articles demolishing Modi’s claims of growth and prosperity, says the chief minister has killed debate in the state.

Some countries such as Singapore and China have benefited in economy management and infrastructure creation under autocratic regimes. But examples from the world over have shown democracy ultimately pays better dividends apart from the obvious benefit of individual freedom. In two comprehensive studies, political scientists Nicholas Charron and Victor Lapuente say that sometimes authoritarian regimes are able to perform better than democratic governments but usually only in the short run and for brief periods. In personalist regimes, “the state becomes an extension of a single individual”, they find. “The impact of democratisation on quality of government is contingent upon levels of economic wealth: At low levels of economic development, democracy is expected to have a negative effect on quality of government, while at higher levels a positive relationship is expected,” they argue. The evidence? Sweden, Switzerland and New Zealand have high levels of economic wealth and greater democracy. Authoritarian governments in China, Qatar and Swaziland have managed to shore up their economies.

Modi’s rule can be best described as personalist, where the state apparatus is geared to do his bidding. One of the main jobs of the apparatus, while delivering governance is also to remind the people who brought it to them. “Modi has no regards for anyone. He has no friends,’’ says Zadaphia, who began his career as a marketing manager with Gabriel and later became an RSS general secretary in Gujarat. The other general secretary was Narendra Modi. Zadaphia was also a minister of state for home in the first Modi government in 2002. I met him the day after Maya Kodnani and others were convicted. When asked about it, he declined comment. “I will not say anything about the cases,’’ he said. Zadaphia, however, had a lot to say about Modi. “We never asked to remove Modi. We only asked for a change of style of functioning.”As I watched from the plane lights in the twin cities of Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar fade in the distance, I wondered why businesspeople consider Gujarat to be their Mecca. I could think of a few reasons, none of which had anything to do with Modi. Gujaratis, it is well known, are enterprising people. The average Gujarati would prefer to start a business rather than work for anyone. As Alagh says, “Gujarat was never big on importing foreign investment, but it was always a technology importer.”

Shreyans Shah of Gujarat Samachar says the state benefited immensely from the White Revolution started by Verghese Kurien. Earnings from agriculture and dairy flowed to the capital markets and savings. The state was blessed with leaders like Jivraj Mehta who laid the foundations of public sector industry Madhav Sinh Solanki who wanted industrial parks in each of the 184 tehsils and even Keshubhai Patel who began massive watershed development with check dams in Saurashtra.

Narendra Modi has inherited a relatively well-functioning state and improved on it with his own brand of governance that works without consultation and debate. Running a relatively homogenous Gujarat like a personal fiefdom is one thing and managing a volatile, diverse country is quite another. That calls for cooperation, compromise, persuasion and deliberation—not exactly qualities associated with Modi. His own party in the state is an example. As Zadaphia says: “In Gujarat, BJP is Modi and Modi is BJP.”

First Published: Sep 24, 2012, 06:26

Subscribe Now