Moser Baer Has All But Shut Down

Moser Baer’s Ratul Puri is struggling to keep the company his father founded and his reputation intact

Ratul Puri, 39, is a charismatic young man. It is impossible not to like him. He is polite to a fault, coolly analytical—a computer engineering degree from Carnegie Mellon helps, no doubt—almost always impeccably dressed in a business suit and smokes Marlboro Lights. He has no hobbies and is a workaholic. No wonder then, that he is usually in office by 10 am and is often the last to leave. If you are an investor you would want someone like Puri to be at the helm of affairs.

Akhil Gupta, senior managing partner and chairman of the Indian arm of Blackstone, one of the world’s largest private equity firms, believes that Puri is one of the best entrepreneurs he has met. Gupta invested $300 million (about Rs 1,650 crore) in a company Puri founded: Moser Baser Projects Private Ltd. This company is an independent power producer and an energy company. “Ratul has reached every milestone before time,” says Gupta, pausing to deliver one of the highest praises an Indian entrepreneur can hope to get, “He reminds me of a young Mukesh Ambani.”

That’s Gupta. Now let’s talk about another investor, Rajesh Khanna. Khanna was the managing director of Warburg Pincus, another blue-blooded private equity firm, who invested heavily in Moser Baer India Ltd, the magnetic storage and solar panel manufacturing company. This is a company where Puri has been a key decision maker. He became the executive director in 2001. While Khanna did not talk to Forbes India for this story, his actions spoke quite clearly.

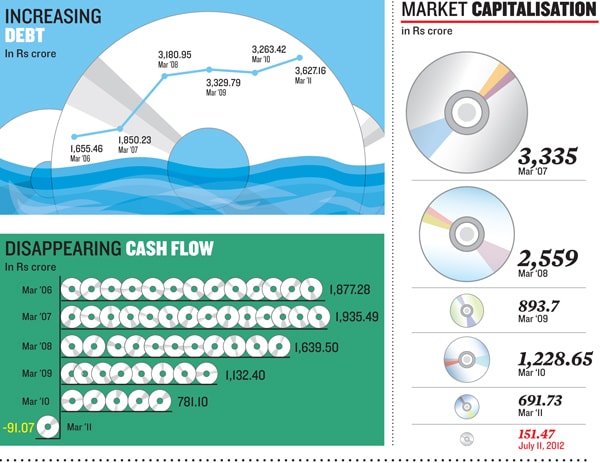

Warburg Pincus recently sold a major portion of its stake in Moser Baer, taking a substantial haircut on its original investment. It is estimated that the fund invested almost $220 million (Rs 1,210 crore) in the company. It sold about 24.5 percent of its stake in an off-market transaction to a Seychelles-based entity called Global Town Investment for about $11 million (Rs 61 crore). And then in June, Rajesh Khanna resigned from Moser Baer’s board. Investing in Moser Baer is possibly one of the worst investment decisions that Khanna must have made at Warburg Pincus.Moser Baer India Ltd, the listed entity, is down for the count. Its sales have stagnated and its cash reserves are totally depleted. Its market capitalisation is merely 5 percent of what it was five years ago. It is unable to service its massive domestic debt. Moser’s cash flow is about Rs 241 crore. And its debt is a towering Rs 3,267 crore as of March 2011. “Either the cash flows or the value of the assets should support the debt. But in Moser Baer’s case both are not adequate,” says a board member of Moser Baer. He requested not to be named.

The company also has foreign debt. Foreign Currency Convertible Bonds (FCCB) issued by the company in 2007 are up for repayment but it doesn’t have the money to redeem them. FCCBs worth $88.5 million (Rs 487 crore) are now being restructured with the help of lenders. Lenders like State Bank of Hyderabad and Central Bank of India have started a corporate debt restructuring programme.

Puri himself has little time for this company where Moser built its equity. “You know there was a time five years ago when Ratul would go wild if the plant was shut even for a few hours. Over the years [in the last three] that has changed to a situation when the plant is often shut down because there are no raw materials and he is fine with it,” says a former Moser Baer senior manager who did not want to be identified.

So, which one is the real Ratul Puri? Is he the phenomenal entrepreneur that Gupta makes him out to be, or a bad businessman who has destroyed capital and almost beggared his shareholders and lenders?

The easy answer is both, but it is also the wrong answer. Business isn’t sport. For entrepreneurs there is no recognition for making a hundred on a viciously turning track the way Sachin gets. If you are in a bad business, you are often portrayed as a bad entrepreneur. This is what happened to Ratul Puri. He is stuck with a business whose best days are behind it.

He is the first Indian entrepreneur of size to be tested and bested both by changes in technology as also the Chinese manufacturing juggernaut.

Brave New World, Brave New Moser

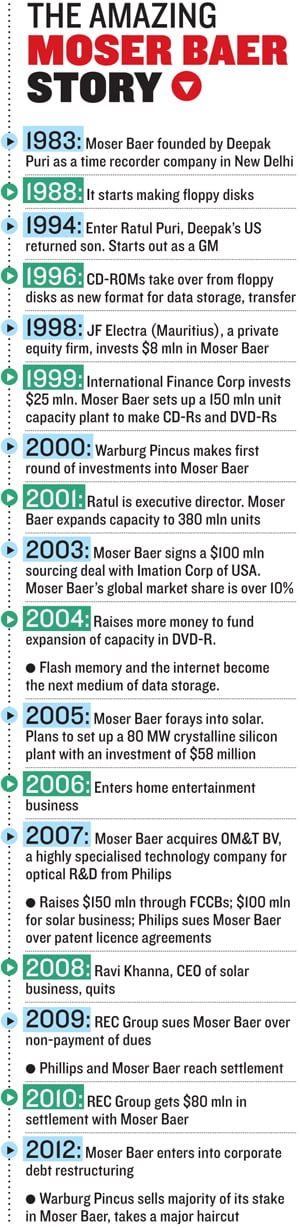

Most people today may not realise what a powerful brand Moser Baer was. Deepak Puri, son of a civil aviation bureaucrat, alumni of Modern School in Delhi and a mechanical engineer from Imperial College, London, started Moser Baer in 1983, after a frustrating attempt at making metal furniture in Calcutta, where he was tired of frequent labour strikes.

Deepak Puri was quick to react and bet on optical media. In 1998, Moser Baer secured funding from International Finance Corp and JF Electra (Mauritius) to fund its entry into the CD-R business. Within a year Warburg Pincus came in, at 12 times the valuation that JF Electra had paid.

When Moser Baer’s revenues were only Rs 154 crore, Deepak Puri raised about Rs 430 crore to venture into making recordable compact discs (CD-R). From 2000 to 2004, the company had a dream run. Revenues rose from Rs 154.34 crore to Rs 1,501 crore. Profits rose about eight times, to Rs 323 crore. Moser Baer grew to become the world’s second largest optical media manufacturer and one of the largest tech hardware exporters from India, shipping to 82 countries.

It was manufacturing several formats like CD-R, CD-RW, DVD-R and DVD-RW. At that time, Moser Baer was churning out about 3 billion discs a year and had a market share of about 17 percent globally.

INNOVATOR’S DILEMMA

It is not known if Deepak Puri or his son Ratul had read The Innovator’s Dilemma by Clayton Christensen, a Harvard Professor. It has an interesting story. Christensen wanted to understand why great firms fail. What better than to study a variety of firms, he thought. His friend advised him against it. The reason as recounted by Christensen is this: “Those who study genetics avoid studying humans because new generations come along only every 30 years or so, it takes a long time to understand the cause and effect of any changes. Instead, they study fruit flies, because they are conceived, born, mature, and die all within a single day. If you want to understand why something happens in business, study the disk drive industry. Those companies are the closest things to fruit flies that the business world will ever see.”

Christensen took his friend’s advice and showed in the book that as disk drives moved through different technologies, firms that were heavily invested in the older version of the technology and customers with older set of needs could not adopt the new ways. They were rendered obsolete. Moser’s situation is so similar to what happened to the disk drive companies that it might be worthy of inclusion in the later editions of the book.

Trouble began somewhere in 2004-05. Moser Baer was still growing in volumes but the profit on each CD started declining. The price of a CD fell from about $1.20 to about 20 cents in just three years. To maintain its volume leadership, Moser Baer needed money to invest in large manufacturing facilities. Should the company have invested fresh capital to invest in business that was seeing its profits disappear? Neither Ratul Puri nor his battery of informed investors thought otherwise. It raised money from Warburg Pincus and International Finance Corp (IFC). The company invested almost $900 million in expanding capacity in 1999-2007. The idea was to build massive, global scale and destroy the competitors.

This never happened. The problem was that Moser’s main competitors—Taiwanese companies like Ritek and CMC Corp—were on to a different game. Even as Moser Baer was raising money for expanding capacity, the Taiwanese companies, both CMC and Ritek were struggling because of several anti dumping duties imposed by Europe and the US. Even in India, the Taiwanese were shut out thanks to senior Puri’s connections in the corridors of power. Everything changed when the Taiwanese decided to move their manufacturing facilities to China. “Once China came into picture, the cost advantage of Moser Baer got completely eroded,” says a senior official in the company.

A far bigger problem was that personal storage in the digital world was changing again. Thanks to the internet, the cost of storage had fallen dramatically. Flash memory was the next big thing for storage and transfer. In an interview with Forbes India in 2009, Ratul Puri had said growth rates fell from a CAGR of 70-80 percent in 2001-03 to about 15-20 percent by late 2004-05. “So you started expanding your capacity and adding capital cost in a falling market,” says a senior Moser official.

Even if the Puris wanted to invest in the new sunrise segment—flash memory—they had little leeway. In this race to the bottom, Puris’ shareholding had got diluted to about 16 percent. The Taiwanese companies, on the other hand, were at a different stage of raising capital. So, they would take loans, increase capacity and at a high value sell their equity. Moser didn’t have that option.Even as all this was happening, the senior Puri had started taking a back seat in the company making way for Ratul. Both father and son understood that optical media’s days were numbered and they needed to derisk the business. Or add a new line of business that would drive future growth and profitability. And it was Ratul’s mandate to find the next business opportunity. He bet on solar.

IMPRESSION SUNRISE

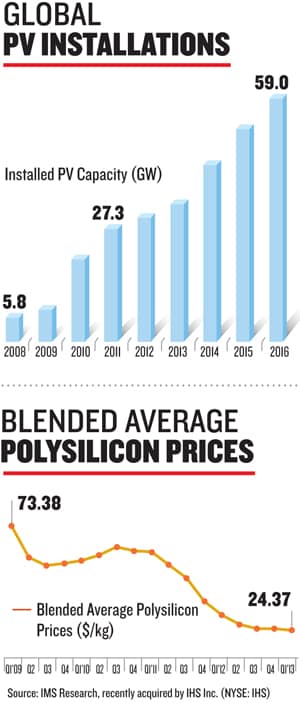

It was October 2005. Ratul Puri knew he had made an impact. In his 77-slide, lengthy PowerPoint presentation to the Moser Baer board, he stated upfront: “Companies in the photovoltaic space are witnessing increasing revenues, profits and high valuations. During the last five years actual growth in the photovoltaic industry has outstripped projected growth by a factor of two. Demand potential of photovoltaic in India is expected to be in excess of 1,000 MW.”

Everybody in the room could see his point. Even the senior Puri, who was earlier sceptical of the solar industry, seemed to agree. After all, how difficult could selling solar cells and panels be in a world which would need more and more energy?

And Moser Baer had the skills to get into the business. The idea was that Moser Baer’s core competency is in micro coating of surfaces. Manufacturing a solar panel is nothing but coating a silicon wafer on a huge glass panel and that’s how the solar business was born.

However, Puri was in a tearing hurry. During 2006-08, Moser Baer invested in a wide range of solar technologies: crystalline silicon, thin film (amorphous silicon)— which it bought from Applied Materials—and a few investments in concentrated solar technology startups like Solaria and SolFocus.

On the supply side, a crucial part of Moser Baer’s strategy was to get access to poly silicon (for silicon wafers), the raw material which was in extremely short supply and used to coat the solar panels. Long-term supply deals were signed with companies like REC Group, LDK Solar and Deutsche Solar, among many others. And then on the demand side, Moser Baer entered into agreements, at the time claimed to be about $100 million (Rs 550 crore), with several power producers in Europe.

Of course, all this needed money. So to fund it, Moser Baer made several financing arrangements. First, it issued FCCBs of about $150 million (Rs 825 crore) in June 2007. In October 2007, the company through its solar unit raised another $100 million from a consortium led by IDFC, GIC Special Investments and CDC group. At the time, Moser Baer said the PE infusion was a crucial step towards a potential listing of the solar entity. And then again in September 2008, Moser Baer raised about Rs 411 crore from a group of investors including Nomura, CDC Group, Credit Suisse, Morgan Stanley, IDFC PE and IDFC. At the time, this bunch of investors valued Moser Baer’s solar business at Rs 6,350 crore.

SUNSET POINT

By 2008, when Moser Baer was just about getting ready for its solar play, the world was hit by a severe financial downturn. And almost overnight, the solar business’ economics changed completely. Till then the photovoltaic manufacturing industry was exploiting the price difference between polysilicon and the demand for solar cells.

Most of Moser Baer’s supply contracts had to be renegotiated. For instance, Solarvalue, one of the companies with which Moser had entered into a supply contract, filed for bankruptcy in May 2012. If that wasn’t enough, Puri complicated his life further by suing one of his suppliers, the REC group. “There was no need for it. I mean this was a company we were chasing for more than five years to sign a contract. And you sue them? Moser Baer didn’t pay them for which REC sent a legal notice. However, Moser said that the product supplied by REC has quality issues which is why the company had held back the bank guarantees. In the end Moser Baer had to settle this lawsuit at a huge cost in London,” adds another former official of Moser Baer. In 2010, REC got hold of bank guarantees worth about $80 million (Rs 440 crore) from Moser Baer.

Through the four years, Moser Baer has suffered. It just didn’t have the cost economics right. “By this time the company had become a nonentity in the business. While the Chinese companies were talking of 2 GW in manufacturing capacity, Moser Baer was 150 MW. That’s nothing,” adds the official.

It also seems Puri had completely underestimated China’s manufacturing potential, which benefitted from the country’s ability to build huge factories quicker and cheaper than any other nation in the world. This was largely due to its inexpensive, efficient construction crews and a process that permitted streamlining. So, while Moser Baer was still taking baby steps in solar, China became the world’s largest manufacturer of solar panels.

According to the China Solar Association, China produced almost 1,180 MW of solar panels in 2007. The Jiangsu province in China alone accounted for 1,000 MW, a quarter of the global total.

OVER AND OUT

Back in Greater Noida at Moser’s manufacturing facility, things are quiet. This solar photovoltaic unit isn’t producing much. And that’s how it has been for the last two years. But the unit in Noida continues to churn out CDs/DVDs to meet whatever demand that exists. Another official who moved out of the company early this year from the human resources department says, “For the last three to four months nobody is going to the plant. They are not getting any salary. The last I heard is that the Noida plant will be shifted to Greater Noida. And the land in Chennai which was bought in 2008 for expansion of Moser’s solar business has been lying barren for the last four years.” What about the business of selling movie CDs and DVDs which Moser Baer had entered with a lot of fanfare and so-called disruptive business model by selling them at ridiculously cheap prices? “That business is finished. It ended a year or so back,” says the official.

Not surprisingly, Puri finds it

better to spend a disproportionate amount of his time in building out the new Moser Baer Projects. His approach is to have a well diversified power portfolio. He is producing power from multiple sources like thermal, solar and hydel. And this company has professionals running the show in each line of business. Gupta of Blackstone agrees that Puri’s execution has been top notch. “Execution is very good with great professionals, regular and robust reviews. Ratul is very hands on, detail-oriented and yet has empowered people,” he says.

But can Puri wipe off the memory of Moser Baer India Limited, the company that his father built from scratch, from the mind of the investors, especially public investors? At some point Moser Baer Projects will go for a listing. Puri will want to now build a business that will reclaim his father’s legacy and redeem his own.

First Published: Aug 01, 2012, 06:47

Subscribe Now