Medtech Giants Philips and GE Fight Over India

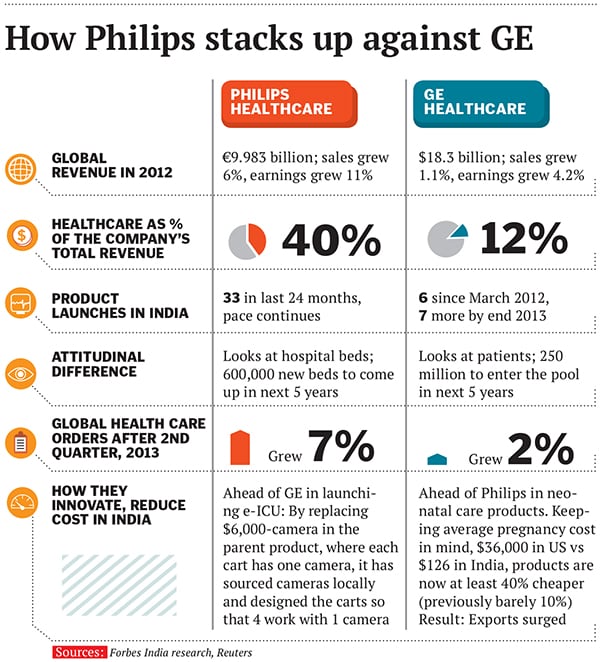

Philips became No. 1 after years of trailing GE in Indian health care. This may change as GE revs up. But both are fighting a battle with their HQs to take the small Indian market seriously

If you are looking for Wido Menhardt, don’t head for the corner office. In fact, don’t even bother looking for a cabin. Because there isn’t one! Instead, Menhardt, chief executive of the Philips Innovation Campus (PIC), prefers to work from one of the open-plan workstations that line the newly renovated floor at the company’s swank 36,000 sq ft facility in Bangalore’s newest technopolis, Manyata Tech Park. Aesthetic, yet spartan, his workstation is indistinguishable from those of the nearly 2,000 engineers that work under him.

The workspace at PIC signifies a culture shift. “The transition from cabin to open office is in line with Philips’s global office strategy —work place innovation... Even Frans [van Houten, global chief executive] and Deborah [DiSanzo, chief executive of Philips Healthcare] don’t have offices anymore,” says Menhardt matter-of-factly.

The cultural change is what global chief executive van Houten is driving through the &euro24.78 billion conglomerate. At a recent conference in the UK, he said it was “an area of ongoing focus in 2013”. Menhardt, for his part, has been experimenting with change across all businesses ever since he came to India in 2010, when 95 percent of the work was in software development. He even coined a slogan—Gurgaon Chalo—to encourage engineers to work with the sales teams.

Philips India is transforming, and the results are particularly heartening in health care. Krishna Kumar, president of the health care division, is cock-a-hoop: “In the last three years, the market, on average, grew 10.9 percent, but we grew at least 2.5x the market.”

In the ’90s, it was Siemens which dominated the Indian health care market. Then GE came and ate its lunch. In the process, GE almost lost its shirt but it pretty much remained the number one medical technology company for many years. At one time, it had the combined market share of Philips and Siemens. Now, it’s Philips’s turn.

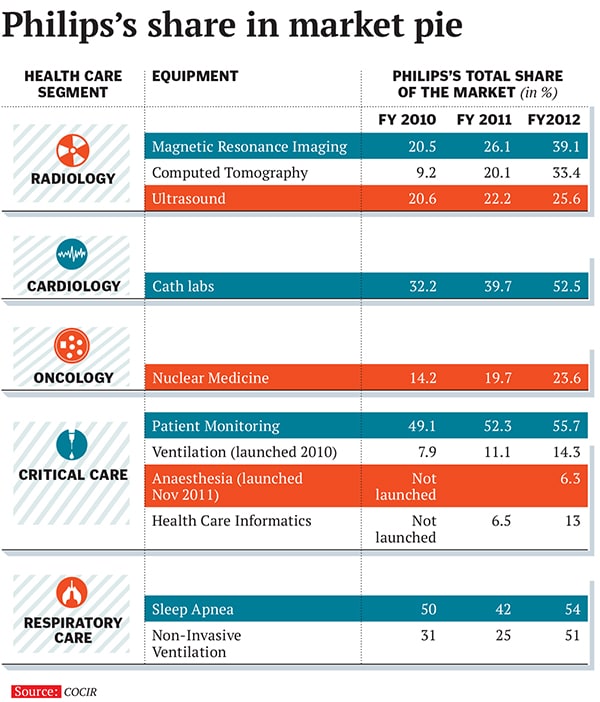

Menhardt and Krishna Kumar (“KK” to friends), who make for a crack team, have rapidly grown market share in the last three years (see graphics, pg 53). In three of the five health care categories that Philips Healthcare sells its wares and competes with GE, it dominates with more than 50 percent market share. GE’s market share is in the “high 30s”.

Philips hired Krishna Kumar just as Menhardt had begun wielding his global experience to aid product development in India. Coming from a medical device company, Johnson & Johnson, he had to speed-learn imaging, scanning and the cornucopia of Philips’s technologies, but in the process he discovered a few unsold ideas. “He comes from a different background…brings a fresh perspective and always talks with numbers,” says Ranjan Pai, who, as chief executive of Manipal Education and Medical Group, has worked with most medical technology companies in India.

Given the cyclical nature of the business, Philips cannot assume it will retain its top dog status for long. What is clear is that a brutally competitive market forces every multinational vendor to sell at the lowest price, forcing it to innovate like it’s never done before. Each is developing its own business model, one that is worth exporting even to developed markets. So, it’s an open question how long Philips can hold its own against GE, which has lined up new initiatives of its own.

GE’s ‘healthy’ goals

On a Saturday in July, the meeting with Terri Bresenham, chief executive of GE Healthcare, is fixed for 10.20 am. It’s at the coffee shop in her residential complex. But when Bresenham arrives, she prefers to meet in the library. It’s quieter there. She’s carrying her coffee and has already been through one morning meeting. A GE veteran of over 25 years, in India she has learnt to optimise, time included. Traffic snarls in Indian cities can’t be wished away, so she sometimes has her meetings, even lunch, while commuting from one customer place to another. Still, she says, she is more optimistic now than when she arrived in India 20 months ago.

It’s a challenging market profit margins are low, there’s tremendous amount of uncertainty—from care provider community to economy— and it’s one of the smaller markets, compared to, say, China, where GE’s business is five times as big. Largely private, with high out-of-pocket expenses due to the narrow coverage of medical insurance, the Indian health care market offers a unique opportunity. “Health care systems the world over are in great economic stress and in search of value. How do we help them in the cost curve…that’s our ultimate objective in how we look at this market,” she says.

Has that exacted a price—like ceding market leadership to Philips?

“Market share is clearly part of the business, but really I’ve never cared for the number one or number two position, provided I had a plan around what the growth of the market is going to be…Being number one or two doesn’t matter to my customers either,” she says. She looks at the tough Indian market as an opportunity to be more innovative. Recently, GE designated India as a centre for “low-cost disruptive products” and it’s no longer about just the technology. It has to be accompanied by a go-to-market and service delivery model.

On the India business now lies the onus of proving the economic value of the technologies it develops, not just on its own terms but along with health care providers and customers. “And then [we have to] repeat the study in Indonesia or Brazil so that we can say, here’s the technology, here’s the clinical proposition and here’s the economic value,” says Bresenham.

After a joint venture with Microsoft in 2012, this past June GE said it’s going to invest $2 billion over the next five years on software for health care systems and applications. India forms a nerve centre in that strategy as well. It is close to signing a deal with a large private hospital where it will implement its IT-Big Data plan. The idea is to take all the incoming information from health care systems—from primary care physicians to large tertiary care hospitals—and aggregate it and use it to improve hospital operations, be it in manpower, capital or equipment.

In a year from now, says Bresenham, GE Healthcare would have changed from being a pure technology provider to someone who stands shoulder-to-shoulder with the operator in improving the outcomes of health care, both in terms of costs and the clinical benefits for patients. It already broke new ground in May in Maharashtra, where it announced a public-private partnership with the state government and Ensocare, part of the $7 billion diversified Enso Group. GE will set up and run advanced diagnostic facilities at 22 government and women’s hospitals, providing services at government recommended rates.

Such partnerships, or at least the intent in other states, are turning out to be reasonably big opportunities. But a business deal with government hospitals comes with its own risks. In 2008, Hewlett-Packard, or HP India, entered into an agreement with the Maharashtra government for computerisation of 19 hospitals. Five years into it, the breakeven isn’t in sight. “We had planned to do three hospitals in four months, but it stretched to one year,” says S Girish Kumar, practice head, healthcare and life sciences, HP India.

The rupee’s slide hasn’t helped global companies either. These accounts were sold when the rupee was at 40, now it’s inching towards 70. HP did not create ‘insulation’ for such volatility, says Girish Kumar. Any other vendor, he believes, would have found it difficult to continue. He is working with three state governments closely but these are open discussions and HP isn’t even close to signing any deal yet.

Any partnership with government may turn out to be an endurance test for companies. Former GE Healthcare Chief Executive V Raja, in whose term GE ventured into a public-private partnership in Gujarat, says if technology companies get into collecting money from the government or hospitals, then probably “every penny will be a pain point”.

One way out of this, says Girish Kumar, is to have tripartite agreements, involving a service provider or system integrator who can convert capex into opex. GE does have a service provider in Ensocare how lucrative this approach will turn to be depends on the execution.

Philips’s soup-to-nuts strategy

Philips’s soup-to-nuts strategy

It was nearly 10 years ago that Royal Philips Electronics decided to become a “connected care” provider, not just catering to patients in hospitals but wherever they are— in ambulances, airplanes or in their homes. It acquired Respironics in 2008 for $5.1 billion, which was the first show of serious intent in home care. (GE formed a home health care joint venture with Intel in 2010 with an investment of $250 million.)

In this connected loop, Philips has been throwing a mix of products. What it did in cardiology, where it claims to be number one in every country it operates in, Philips intends to copy in other fields. Out of 1,030 cath labs used in India, 650 are from Philips. It has the cheapest as well as the most expensive cath labs in the world. (Cath labs are all-equipped examination rooms for providing diagnostic and interventional cardiology procedures.). More range will be added to its products, thanks to its new manufacturing facility in Pune.

Krishna Kumar may like to argue that it’s not “just” about pricing, but the reality is price has been the swinger. “Both have good technologies but Philips is a cut above the rest in service level back-up and initial pricing,” says Pai. A local Indian manufacturer which competes with these two companies in a handful of products says Philips’s “aggressive financing” has given it the edge.

In a market where banks, barring HDFC Bank, don’t fund medical equipment, Philips has come with a war chest. GE and Siemens have been financing their equipment in India, the former through GE Capital, the latter through Siemens Financial Services. But Philips came with new ideas. It started offering turnkey solutions, along with financing for both equipment as well as solutions. “In the five verticals we operate, we can do up, say, an entire cardiology or radiology unit and hand over the keys to the hospital,” says Krishna Kumar.

It’s not surprising then that nearly eight out of 10 large new hospitals with more than 150 beds are partnering with Philips (see graphics on pg 57). Where Philips is giving GE a run for its money is serviceability. Philips’s new support centre in Chennai fixes nearly 40 percent of complaints of systems going down through one call. Some 85 percent of its installed capacity is connected all the time and can be monitored efficiently. If, say, a diagnostic chain has 10 MRs (magnetic resonance) or CT scanners, Philips can see their utilisation rates in real time and do internal benchmarking.

Traditionally, GE has made more money on services, with hefty margins. Philips did not copy that it has worked with thin margins. By and large, Philips has learnt the game from GE and is improving it, says Raja, managing director and president of TE Connectivity India, part of a $13.3 billion cables and interconnect products maker. How far is it sustainable? he asks. Still, he gives credit to Philips for capturing 40 percent market share in radiology. “MR reflects the technology of a company and if you’ve played across the country, created brand saliences among key radiologists, then you’ve arrived.”

Sustainability will come from product innovation it’s a no-brainer. Menhardt knows this. He’s been an entrepreneur in his past life, before he started his second stint at Philips in 2007. At PIC, he’s made changes at the beginning of the product cycle. “Earlier, if our engineers wanted to see customers to understand product design, they had to go to the US or Holland we didn’t have clinical relationships in India. Now, we have beta sites in the country,” he says.

Menhardt has good reason to chart a new course. At MiraMedica, his startup in California which was acquired by Kodak in 2004, he often took the path less taken. At one point, his team was building an artificial intelligence device—for automated cancer diagnosis in mammograms. It was a software-only device but came integrated with an off-the-shelf PC. All previous devices in that category were registered with the US FDA as hardware/software combos. This presented a problem, as any change in the software required a fresh FDA review. Menhardt wanted to meet with the FDA to get approvals for a software-only device, but the MiraMedica board was uncomfortable doing anything unconventional. They recommended meeting a regulatory law firm.

“The law firm was very expensive. I remember I could see the White House from the conference room. Their feedback was—you can’t do this. I asked why not? They said—because it has never been done before!”

That night, in 2003, Menhardt had to make a difficult choice follow the lawyers’ advice, or do what he thought was right. He met with FDA officials the next day. They listened, they understood, and agreed. MiraMedica went through the whole submission and approval process in record time.

Menhardt brings this approach to PIC in Bangalore. “Sometimes we do things that are not the conventional approach in a large MNC, and often we are told that you can’t do that, but if we think it’s right, we go ahead, and it has paid off so far,” he says.

In 2011, he set up the mobility competency centre at PIC. Today, it is the go-to-centre for mobile applications for Philips globally. It has had some successful releases in the Hue, the smartphone-controlled lighting system automated espresso maker Saeco and IntelliVue mobile patient monitoring.

A geek to boot, a surfer and skier to the hilt, 53-year-old Menhardt makes sure PIC rallies around a technology theme each year. If it was mobility in 2011, it was connected devices in 2012, and Big Data in 2013, where it is collecting proof points for business cases.

Krishna Kumar, who considers Menhardt his “long lost Austrian-American brother”, says he takes a cue from his work. “I try to give solutions to my customers even before they ask for it,” he says, then narrates a slew of medical studies that Philips is undertaking. Use of spectroscopy in screening breast cancer or of functional MRI, with inputs coming from Devanagri script, are some of the world’s first from India.

If not an outlier, it’s certainly a rarity that a business head vibes so well with an R&D nerd. Kumar clarifies though that they “do give grief to each other at times”. As an outsider, it’s easy to see that at 6 ft, Menhardt may be two inches shorter than Kumar, but they manage to see eye to eye.

Competing in the best of times, worst of times

In July, the two medtech majors announced their global second quarter numbers. Philips Healthcare continues to have wind on its back. Profits in this quarter grew 67 percent GE Healthcare reported a 5 percent profit increase on flat revenues. Healthcare in GE may not be a strong point now (see graphics on pg 54). In India, perhaps as in the rest of the markets, it’s in the throes of change. “It may not be number one today but I am sure we’ll also hear success stories of Terri,” says Pai.

In scripting her new stories, Bresenham has top management support. “I do the translation for the global office, make India’s case bigger…For most multinationals, India is not even 5 percent of their [total] revenue,” she rues. Indeed, at $570 million, and growing at 15-16 percent over the past five years, the health care business in India is still small change for the $18.3 billion parent health care division.

It’s a sticky issue for global companies, one that Ravi Venkatesan, former chairman of Microsoft India, has dissected in his recent book Conquering the Chaos: Win in India, Win Everywhere. He says many MNCs are quite pleased with their performance in India because they have set quite a low bar for success. Most Indian units, despite growing in double digits, are often irrelevant to their parent companies. The single most important determinant of success over time, says Venkatesan, is the choice of the country manager.

As Bresenham ‘translates’ India’s potential to her global counterparts, Menhardt makes frequent trips to the headquarters in Amsterdam as well as to the US. While his predecessor made annual trips, almost like a vacation, he’s meeting global teams every six to seven weeks.

“What do you do?” I ask.

“I do what you do communicate,” he quips. “India is far away its revenue share is small, so we have work there. I tell them what capabilities we’ve built, how we have the lowest attrition…I build credibility and get autonomy…I have to do a lot of legwork to make that happen.”

It is obvious that Menhardt-KK and Bresenham are trying to break out of what McKinsey calls the “midway trap” and are getting their parent companies to invest in India. Last year, GE Healthcare spent $1 billion, or 5.4 percent of its sales, on R&D. Philips Healthcare spent 11 percent of its revenue.

In percentage terms, its India spend is higher though not entirely comparable. GE won’t give the break-up either but says it’s not a function of local sales, acknowledging that investments have increased “dramatically”. Bresenham says: “We figured what we can do in India.”

One of the new initiatives that she is driving is to partner with health care providers. GE has formed a special purpose vehicle with India’s largest cancer care provider, Health Care Global (HCG), to open 40-50 cancer centres in India in the next few years, focusing on diagnostics. In the coming months, she’s going to announce a similar programme in mother and child care.

Maybe she’s done a gut check on this approach but many think it’s a difficult proposition to pull off. It can also be seen as GE competing with its customers. If GE wants to work with Fortis in cancer care, how will HCG handle that? Has it signed a non-compete agreement with GE? HCG founder-chairman Dr BS Ajaikumar believes, in any such event “at the broad level it’s the SPV that will be involved, though not at the delivery level. We’ll look into such deals closely.”In another eyebrow-raising step, Bresenham wants to do a Nasscom in health care. Called NatHealth, this industry body will both guide and lobby government on health care issues. Last year, GE Capital invested in Biocon group company Syngene (which is on the cusp of going public) and Bresenham says she is evaluating two more investments in biologics and life sciences.

Just how big is her vision? “We want to see a healthy India,” she says, softly.

Philips isn’t willing to be drawn into any such debate its focus is on customers. The relentless stab at launching new products, 33 in the past 24 months, and seeding new research sites will continue. It claims that its Pune manufacturing facility, which makes products for the global market, shows the kind of commitment which no other multinational exhibits today, at least in health care. Of Philips’s Rs 5,579 crore revenue in 2012, health care contributed 18 percent, but it’s projected to go up substantially this year. On the other hand, GE, with about $2.8 billion in revenue from India, has nearly 20 percent coming from health care.

“Both Philips and GE should have less than 5 percent of the revenues coming from their local manufacturing initiatives and this is nothing compared to their investments and scale of manufacturing operations in China or Brazil, where they were forced to make substantial investments,” says an Indian medtech entrepreneur.

Now that we see some investments, it’s coincidence that two expats are driving this. “Nationality is immaterial,” says Venkatesan. As long as they are trusted by their headquarters, are entrepreneurial, and passionate about the country and have guts, they will be effective, he says, adding hastily that the tenure is no less significant. “They should be here at least five years, if not seven.”

Neither would comment on that. But Menhardt has picked up some local vocabulary. When we asked if Philips was finally ready for a “healthy” battle with GE, he looked at Krishna Kumar and said: “Swalpa, swalpa (Kannada for ‘little bit’)”. The latter is more aggressive though: “Right now time is ours ours to take or ours to lose.”

First Published: Sep 16, 2013, 06:40

Subscribe Now