Maruti rebooted: Driving a new growth story

The last five years have seen India's largest car maker adapt to new consumer expectations and emerge in a shinier, tech-savvy avatar

The killing shook Maruti Suzuki—and India. On July 18, 2012, a group of workers at the automaker’s Manesar plant in Haryana armed themselves with rods and door beams of cars and fanned out across the facility. They hunted down and attacked the management staff violently. Awanish Kumar Dev, head of human resources was burnt to death and scores of management staff, including two Japanese executives, were injured, many seriously. Disciplinary action by a supervisor on an errant worker was the trigger for this gory attack. Maruti’s labour relations hit a new low. There were fears of virulent labour militancy.

For the auto major’s top management, this incident seemed to shatter the hope of sustaining a revival it had painstakingly effected towards the end of the 2000-2010 decade.

The worm of discontent had been crawling upward.

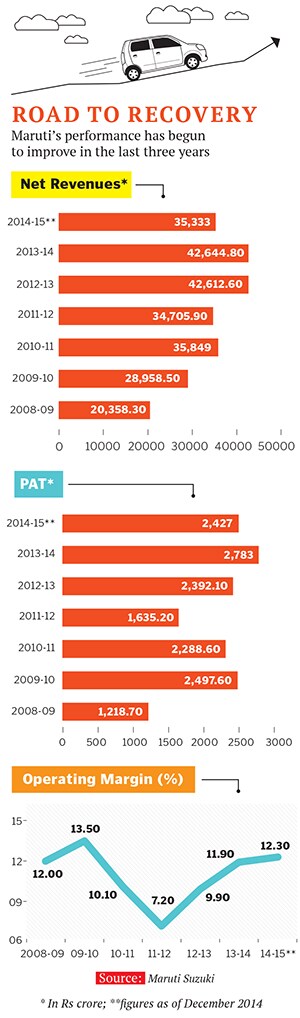

During the fiscal year 2009-10, Maruti’s net sales had grown by 42 percent (against the industry’s 26 percent) to Rs 28,958.5 crore and, more significantly, net profit more than doubled to Rs 2,497.60 crore (see ‘Road to Recovery’). Boosted by the launch of successful new products such as Swift and Dzire, Maruti protected its 45 percent market share that year. Operating- and net profit margins at 13.5 percent and 8.6 percent respectively were inching to levels that were among the highest in 10 years. It appeared that the company had finally weathered the storms it had faced over most of the decade—from the entry of global car majors into India to the tussle between its two joint venture partners, Suzuki Motor Corporation and the Government of India, which culminated in the former taking a controlling 56 percent stake in the company. This tumultuous period saw Maruti’s market share dropping from a heady 80 percent prior to 1998 to below 45 percent by 2000. “We thought in 2009-10 that the worst was behind us,” recalls 81-year-old RC Bhargava, chairman of Maruti Suzuki India Limited. He could not have been more wrong.While the Manesar violence may have been the gruesome face of its turbulence, a series of events had been unfolding since 2010-11 and was impacting Maruti severely: The extreme volatility in foreign exchange rates, a sudden consumer preference for diesel cars and fundamental changes in the Indian car market, which saw reduced model life cycles, and a clear shift in demand away from Maruti’s core market left the company reeling. Its market share in 2011-12 fell to an all-time low of 38.3 percent, operating profit margins fell to 7.2 percent while net profit margin slumped to 4.7 percent. “It was clear that Maruti’s traditional strengths—manufacturing excellence and distribution reach—were alone not enough for the company as a competitive advantage anymore,” says BVR Subbu, former president of Hyundai Motor India Ltd.

It was time for the company, which launched the iconic Maruti 800 thirty one years ago, to don a new avatar.

For Kenichi Ayukawa, who took over as managing director and chief executive officer in March 2013, it was baptism by fire. A Suzuki veteran, he was experienced in selling cars in the Indian subcontinent, having headed Pak Suzuki Motor Company for four years. He was also a member of the Maruti Suzuki board since 2008. “The market was clearly changing. Customer expectation was changing, and it was clear to me that we needed to adapt if we are to remain the top car maker in India,”

says the 60-year-old Ayukawa of his first impression after taking over at Maruti.

By the time he arrived, Maruti’s top management had already started the process of reinvention by questioning almost everything the company had been doing till then: On indigenisation, quality, plugging product gaps, entering new segments and developing new products in India. He and Bhargava accelerated the process.

This vigour has led to the emergence of a new Maruti a company now better prepared to face external shocks, nimble enough to ward off domestic competition, and with a labour force that is involved in its operations and committed to its future. It posted its highest-ever domestic sales of 11.71 lakh units in the 2014-15 fiscal. In areas such as technology, too, it has begun to behave like a market leader.

This is a case study in what five years can do when the elephant is prepared to dance.

Lesson No. 1: Go local to adapt quickly

It all began in 2010-11 when volatility hit the global currency markets. The Japanese yen appreciated sharply against the US dollar, as did the rupee. The currency interplay resulted in the rupee-yen exchange rate turning adverse. From Rs 0.32 buying 1 yen in 2007-08, it became Rs 0.70 to a yen.

Maruti, even as late as 2011, continued to have—directly and through vendors—a 28 percent import content from Japan. “The high quality parameters that Suzuki had set meant that we had to import steel, copper and other items,” says Bhargava, justifying the decision. But critics have always panned Suzuki for keeping indigenisation levels low to aid higher exports from Japan. “How other global car majors like Hyundai and Ford managed a far higher level of localisation without compromising on quality is one question Maruti and Suzuki found difficult to answer,” says Subbu.

Maruti took a beating for this. “At its peak, the margin erosion on account of the stronger yen was in the order of 7 to 8 percent,” says Ajay Seth, executive director and chief financial officer of Maruti Suzuki. It forced the company to revisit the issue of localisation to reduce yen-denominated imports, and work with vendors to cut import content to 15 percent. “This crisis opened our eyes. We realised that inner components for critical parts that need to be imported can be procured here. For decades we had been importing them, too,” says Bhargava.

These efforts have boosted Maruti’s margins. “Even if the yen appreciates to the levels it did in 2011-12, the margin erosion will be only 4 percent,” says Seth. (The yen currently trades at Rs 0.52 levels.)

Once it reduced its dependence on Japanese imports, Maruti began to focus on exports, which had traditionally been 10 percent of overall sales. “Higher exports will enhance our natural hedge against a volatile US dollar, and so we began exploring new markets,” says Seth. In 2014-15, three years after it refocussed its strategy, the automaker announced that its exports had grown by 20 percent in 2014-15 over the previous year (see ‘Back with a Bang’).

Maruti was also caught on the wrong foot by the shift towards a preference for diesel cars in India, triggered by the widening difference between petrol and diesel prices after the government de-regulated the price of petrol in 2010 while continuing to regulate that of diesel. The gap, which was around Rs 15 per litre before the policy change, widened to about Rs 29.8 in September 2012. Diesel cars became more attractive, but manufacturing them was not Maruti’s forte. Only 17 percent of its cars till then had diesel engines. To complicate matters, parent Suzuki was not a diesel player either. Between 2011 and 2013, the petrol-diesel ratio of cars sold in India changed from 64:36 to 42:58. While competitors such as Hyundai Motor Company, Tata Motors and Ford Motor Company sold diesel cars at a premium, Maruti struggled to sell its petrol models despite discounts that, on an average, exceeded 7 percent. In 2011-12, its market share hit 38.3 percent, the lowest ever. “What made things difficult for us was a lack of clear government policy on petrol-diesel pricing,” says Bhargava.

To fix this, Maruti reached out to Fiat and ramped up its diesel engine capacity. (It was already procuring diesel engines for Swift from the Italian automaker.) This move, to an extent, helped it ride out the crisis, which began to ease after the deregulation of diesel prices last year.

In 2014-15, the price difference between the fuels was about Rs 8 per litre, and the petrol-diesel ratio of cars sold retracted to 52:48. While this has helped Maruti, it has birthed another problem: Using its expanded diesel engine capacity optimally. And, more importantly, adapting quickly to sudden shifts in future demand.

Over the last couple of years, Maruti has introduced a good amount of flexibility in its operations. The lessons learned are now ingrained across rank and file. “Flexibility is critical at times when the market shifts dramatically, both in terms of product segments and engine type. In the future, we are looking at producing both petrol and diesel engines in the same line,” says Rajiv Gandhi, executive director (manufacturing).

Predicting demand is another area that Maruti is fine-tuning. “Government policies will continue to impact the business. Foreseeing them and creating scenarios is critical. We are strengthening that capability,” adds CV Raman, executive director (engineering).

But before Maruti could become as nimble as its rivals, it had to innovate.

Lesson No. 2: Invest in technology

Other changes in the market (around 2010-11) were also affecting Maruti’s sales. For one, the entry of international heavyweights like Ford, Nissan and Renault into the compact segment saw competition increase in its core market. Customers, spoilt for choice, were becoming harder to please. “Technology and new product development will be key differentiators in the Indian auto market,” concedes Raman.

Historically, Maruti was not known for either. “For the first 10 years of its existence, there was no competition. There was neither the motivation nor the pressure to be agile. In those days, it was also difficult to bring technology into India on account of foreign exchange issues,” admits Bhargava. “Later, ownership issues surfaced. Companies do not share latest technologies with each other unless they have management control.”

These developments saw Hyundai’s Santro (launched in 1998) grab a large chunk of Maruti’s market share by introducing technologies such as power steering and multi-point fuel injection. In mid-1999, Maruti suffered the ignominy of not being able to sell a single car in New Delhi (India’s largest car market) as its models were not Euro II compliant.

If there was one area where Maruti had failed as a market leader, it was in introducing industry-leading technologies. That had to change, but to do so, it had to break from a tradition which dictated that innovations could only be offered in premium cars. The logic was that while buyers of compact cars may not have deep pockets, buyers of higher-end models would pay more for new technologies. But with most of its sales in the former segment, Maruti had to go the Hyundai Santro way: Innovate without increasing costs. “We set a goal of developing products that have good design, introducing technology where the cost of acquisition is low, and maintaining an operating cost that is best in class,” says Raman.

Maruti’s first successful innovation was the introduction of its auto gear shift technology earlier this year. It offered the convenience of automatic transmission, but at a lower cost (Rs 40,000 as opposed to Rs 1 lakh) and without compromising on fuel efficiency. (Suzuki began working with its Italian supplier, Magneti Marelli, to develop this technology.) “The reason why the share of vehicles with automatic transmission in India is less than 1 percent compared to 99 percent in Japan and the US is the high cost of acquisition of the technology and the resulting 5 to 10 percent reduction in fuel efficiency,” says Raman. But Maruti was able to find a way around this, and use this technology in the Celerio and Alto K10, both compact models. The cars have been well received, so much so that a new auto gear shift line is being added at the Maruti-Magneti Marelli joint venture facility in Manesar. CEO Ayukawa expects 30 to 40 percent of small car models to sport auto gear shift technology in the near future. And for the first time in its recent history, Maruti has taken the technology lead.

The other area of focus has been fuel efficiency. The new Dzire, launched earlier this year, has the highest fuel efficiency in the automobile industry (Rs 26 kmpl for diesel and 20 kmpl for petrol). Maruti is also looking to adapt some of the recent technological successes that Suzuki has achieved, like a 660 cc petrol engine with a fuel efficiency of 37 kmpl, booster-jet technology that makes smaller engines more powerful, and a hybrid vehicle system. “The challenge is to bring these technologies into India at the right cost,” says Raman.

Lesson No. 3: Refresh and update products regularly

The automaker is gearing up to introduce three new cars over the next 12 months. It has mapped an active product line, with 14 new models over five years. “The lifecycle of a model has shrunk from 10 or 15 years to five years. There is an urgent need to keep excitement levels high through frequent product launches and refreshes,” says Raman. This level of activity and energy is a new phenomenon the automaker’s record when it comes to launching models has been patchy: For more than 15 years, the Maruti 800 was its mainstay the Esteem and the Zen were the only two offerings from mid-1980s to mid-1990s the Wagon R entered the Indian market in 1999. By then, the Santro, a car inspired by Wagon R’s tall-boy design, had eaten into its market share. The pace improved by the turn of the century when Maruti rolled out five models—Swift, Dzire, SX4, Ritz and A Star—between 2000 and 2010.

This level of activity and energy is a new phenomenon the automaker’s record when it comes to launching models has been patchy: For more than 15 years, the Maruti 800 was its mainstay the Esteem and the Zen were the only two offerings from mid-1980s to mid-1990s the Wagon R entered the Indian market in 1999. By then, the Santro, a car inspired by Wagon R’s tall-boy design, had eaten into its market share. The pace improved by the turn of the century when Maruti rolled out five models—Swift, Dzire, SX4, Ritz and A Star—between 2000 and 2010.

There is a reason for the stuttering product launches: Most of Maruti’s research and development (R&D) takes place in Japan. The facility caters to multiple markets such as Indonesia, Japan and the US, which means higher lead time. In his memoir Driven, Jagdish Khattar, who was the MD and CEO of Maruti for eight years, highlights this problem: “Bhargava had suggested to Suzuki in the mid-1990s that India needed diesel engines because of local preference and due to the fact that diesel was much cheaper than petrol. Despite our repeated exhortations, the reply was that there was not much market for diesel in Japan or the United States.”

Rapid changes in the Indian market of late, however, have forced a change in thinking at Maruti and Suzuki. The company is setting up a full-fledged R&D centre at Rohtak, Haryana, including a state-of-the-art test track at a cost of Rs 2,000 crore. The facility will be operational next year.

Is this move 30 years too late? “Even 10 years ago the volumes in India did not justify setting up such a facility,” says Raman. The new facility will work with Suzuki’s Japan R&D centre. “The easiest part is setting up the infrastructure. Getting the right people is a challenge even today. We need experienced people to develop great cars.” That said, Maruti has been preparing its people in product development. Engineers are routinely trained in Japan. In 2003, about 25 engineers were part of the Swift development team. The Alto 800 was developed entirely by Maruti engineers while the validation part was undertaken by Suzuki Japan.

With its new R&D centre on track, the automaker, which made its name in the hatchback segment, is showing signs of bullishness in the premium sedan segment.

Lesson no. 4: Think Big

The other big emerging challenge is the gradual shift in demand away from Maruti’s core market. According to a research report by CLSA, the share of small cars in the passenger vehicle industry has fallen from 68 percent in 2010-11 to 52 percent in 2014-15, while the share of higher-priced segments such as sedans, multi-purpose vehicles and urban SUVs has risen from 24 percent to 41 percent in the same period. “Improving the acceptability of the brand at higher price points is crucial for Maruti,” the report adds.

Maruti has brought in successful models like the Swift and Dzire to meet this growing demand in the premium compact segment where prices range from Rs 4.5 lakh to Rs 8 lakh. The challenge is in the SUV and the premium sedan segments: Its attempt to import its premium sedan Kizashi recently and its SUV Grand Vitara a few years ago failed because they were too expensive. It launched a sedan SX4 in 2007, which failed after some initial excitement as rivals offered better vehicles.

But Bhargava is unfazed by these setbacks. “Percentages are deceptive. Yes, as people become prosperous they will expect more features in a compact car. We are ready for that, but I am still not convinced that India will become a large market for bigger cars,” he says. Ayukawa agrees: “Maruti was started 30 years ago to produce affordable cars. We will stay true to that focus.”

Nevertheless, the company is expanding its product portfolio to have a larger footprint: It recently launched a premium sedan Ciaz (Rs 9 lakh to Rs 10.5 lakh), which has been well received in the market, and is selling 5,000 units a month it will be launching a compact SUV and a crossover in the next one year. “Maruti [post Ciaz’s launch] has a strong presence in 84 percent of the passenger vehicle market. If the upcoming SUVs get a good response, this will rise to 92 percent by 2016-17,” says Abhijeet Naik of CLSA in his report.

Will Maruti now launch products that straddle the Rs 10 lakh to Rs 15 lakh segment? Ayukawa is circumspect. “First we need to build volumes of Ciaz from the current level of 5,000 to 10,000. We will consider bigger cars after that,” he says. But RS Kalsi, executive director (marketing and sales) is more forthcoming: “We will be going into the Rs 10 lakh to Rs 15 lakh segment with our SUVs and premium sedans.” These launches will ensure that Maruti does not lose loyal customers, which it did till recently for want of options to upgrade. Lesson No. 5: Strengthen the core

Lesson No. 5: Strengthen the core

Even as Maruti addressed its weaknesses, it began to bolster its core strengths. “Continuous improvement is a way of life at Maruti, and employees are fully involved in it,” says Gandhi. As the market turned adverse, the management looked to its employees for suggestions. They had another reason to do so. The Manesar plant had seen three strikes in 2011. The thinking within the management was that employee involvement there was not as strong as the older Gurgaon plant, which had better labour relations. Also, the employees at Manesar were younger and their concerns needed to be handled differently. In a move that highlighted a policy of inclusiveness, the company began to involve them more deeply in seeking suggestions.

In 2009-10, the number of suggestions received from employees was 1.29 lakh, and, when implemented, they saved costs of Rs 203 crore. By 2014-15, the number of suggestions had risen to 5.62 lakh and annual savings amounted to Rs 394.60 crore. “The suggestions revolved around yield improvement, better inventory flow, higher productivity, lower down time and savings in power costs,” says Gandhi.

Another advantage is Maruti’s vast distribution reach, built during years of monopoly, which has always been a source of envy among its competitors. As demand declined, the car maker began aggressively expanding its reach, and tapping potential customers in smaller towns and cities. In 2009-10, Maruti had a sales network of 802 showrooms in 555 towns and cities. By the end of 2014-15, this increased to 1,619 across 1,290 cities and towns. It increased its service centres from 2,740 to 3,086. “This move has helped us increase our rural penetration from 16 percent in 2009-10 to 32 percent in 2013-14,” says Kalsi. The company also expanded its used-car network, True Value, to 648 towns and cities: Almost 30 percent of its sales now come from car exchange.

Today, Maruti is a better company than what it was five years ago. It is less exposed to currency risks, can deal with market changes more nimbly, has a strong product pipeline, a larger footprint in terms of product segments, and will have a full-fledged R&D facility soon. The company is well on its way to reaching its 2009-10 margins and market share.

So how important is Maruti for Suzuki today? “Very important,” says Bhargava. That partly explains why Suzuki has chosen to invest Rs 10,000 crore directly to set up facilities in Hansalpur, Gujarat. It will increase the manufacturing capacity, currently at 15.1 lakh units a year, by 100,000 cars per year when operational. The Gujarat plant will make cars to Maruti’s requirements and sell them at cost to its Indian arm. The move has ruffled a few feathers among investors, and some sceptics say that Suzuki’s plan seems too good to be true. But Bhargava brushes aside these doubts. “Don’t forget, Maruti is its biggest subsidiary and Suzuki recognises that its future is critically dependent on Indian operations,” he says.

By not having to invest in the Gujarat plant, Maruti is left with a Rs 10,000-crore war chest to spend on product development and distribution. This cash pile, and the company’s recent transformations, just might see it achieve its dream of selling two million cars in India by the year 2020. For now, the car maker seems to have removed the speed barriers ahead.

First Published: Apr 27, 2015, 06:11

Subscribe Now