L&T: Armed but not commissioned

Though affected by the 'lost decade' like the rest of the Indian private sector with ambitions in defence manufacturing, L&T's chief AM Naik is determined to persevere with his firm's big dream

By the end of his tenure as defence minister earlier this year, he came to be known as St Antony.

Reason: Though his eight years were coloured by inaction, apathy and multiple shades of grey—think blacklisted vendors, cancelled contracts and stalled projects—AK Antony, almost effortlessly, managed to keep his mundu spotless.

But not much else stayed unaffected by his immobility in decision-making.

One: The Indian Armed Forces were hit because timelines on equipment purchases, which are long in the best of times, got stretched indefinitely.

Two: Contracts were tendered and re-tendered, but a lot of vital equipment was never ordered.

Three: Arguably the most lasting impact of Antony’s stay-safe policy is the setback to India’s military-industrial complex that is still struggling to take birth.

Within the industry, they call it the ‘lost decade’. Consider that around 70 percent of the country’s armaments are now imported—in 2011, India replaced China as the world’s leading arms importer. By 2010, the government’s plans to build Raksha Udyog Ratnas, high-potential Indian companies that could be groomed to become large manufacturers and exporters of defence equipment, went into cold storage.

Most of the contracts placed with domestic companies went to defence PSUs such as Hindustan Aeronautics Limited, Mazagon Dock Limited and Ordnance Factories Board. The upside: For the ministry, a straightforward way to avoid any corruption taint was to shut the doors on the private sector. The result: For private sector companies, orders were few and far between. Analysts say total defence-related orders for the private sector (including exports) were below $2 billion last year—this is less than six percent of India’s total defence spend.

Despite the slowdown, there were a few contrarians. Entrepreneurs and companies, who stayed in the game, hoping for change. These were obviously companies who had the cushion of other profitable businesses: They continued to build, hire and invest hundreds of crores of rupees, with the expectation that bigger contracts would eventually come their way.

The hopefuls include the Tata Group, Mahindra & Mahindra and, to a lesser extent, companies such as Bharat Forge, Pipavav Defence and Ashok Leyland. But, by far, the biggest and most ambitious of them is Larsen and Toubro (L&T) which has invested and built ahead of time to cater to all three defence forces. Like much else in the company, the push is led by their 72-year-old group-chairman AM Naik, who completes half a century at L&T next year.

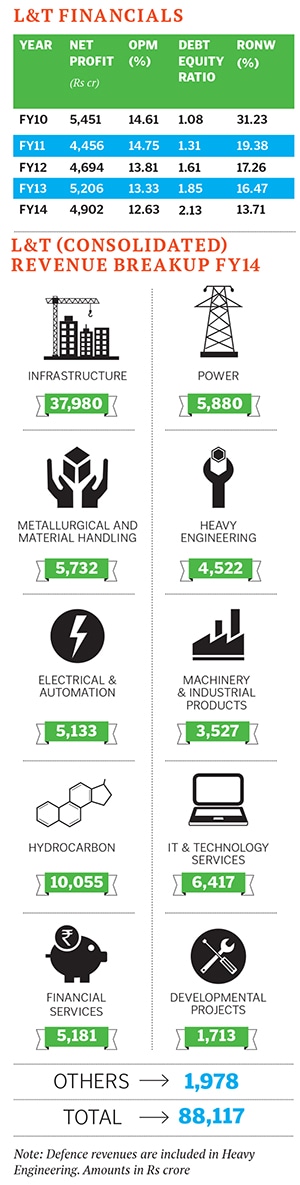

L&T has invested close to Rs 5,000 crore in its defence and nuclear business, Naik told Forbes India in his trademark no-holds-barred style in his Mumbai office. “The idea is to build our capability and not just capacity. Anybody with money can build capacity,” he says. L&T’s strategy has been to prepare for higher-end work by building competencies at its own facilities as well as through joint ventures. Infographic: Sameer Pawar Data Reasearch: Kishor Kadam, Firstpost

Infographic: Sameer Pawar Data Reasearch: Kishor Kadam, Firstpost

But the orders aren’t rushing in. Compared to its topline (Rs 56,598 crore) last year, income from the defence business is miniscule—just about Rs 1,200 crore of the engineering giant’s total revenues (about two percent). This could change quickly if the new government is able to break out of the inertia, says Naik. “If the government is able to announce a new policy and tenders come out, the defence business could go up to 10 percent of L&T’s turnover in three to five years,” he says.

L&T’s presence in defence is spread across several specialised areas and includes joint ventures and partnerships with global majors for composites, avionics and control systems. However, few projects are as visible (or capital intensive) as its ambitious goal to become a Warship builder.

Nation Building

Naik’s search for a greenfield site to set up a shipyard was being conducted at a time when the ship-building business was struggling around him. This was 2007 and the government had just stopped the subsidies that were provided to commercial ship-builders in the past. But Naik was undeterred—his efforts were driven by a tantalising dream of producing a line of submarines.

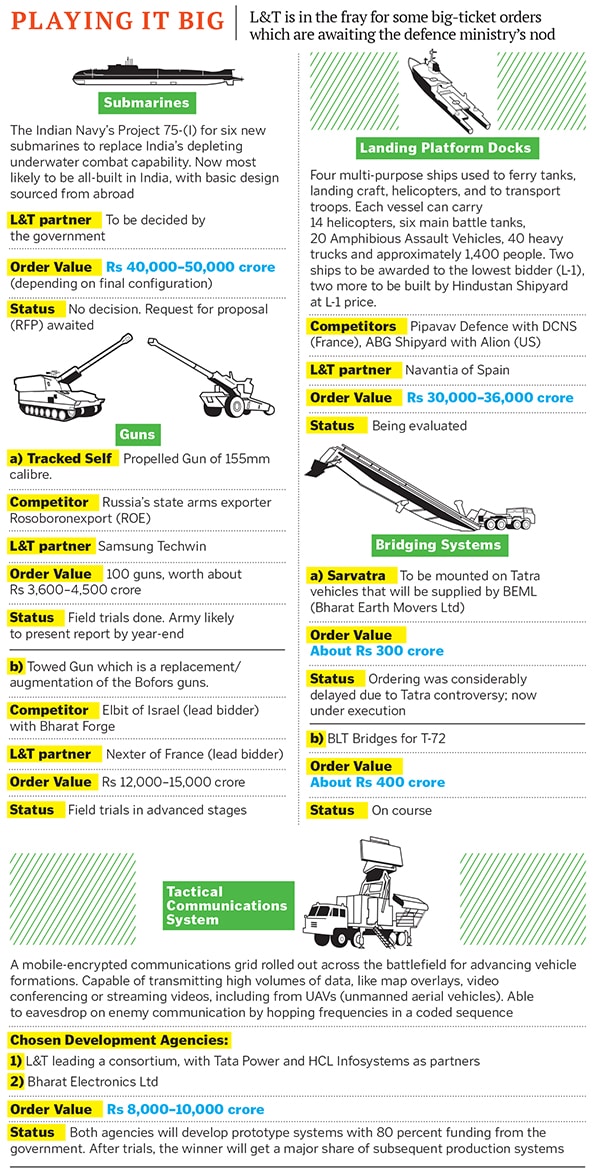

When the last BJP-led government was in power in 1999, the cabinet had approved a 30-year submarine building plan. Twelve new submarines were to be constructed with foreign collaboration by 2012, while another 12 were to be ‘built to indigenous design’ from 2012 to 2030. It was the second part, code-named Project-75 (I) and worth Rs 50,000 crore, that Naik wanted to be prepared for.

He accepted the M Karunanidhi-led DMK government’s offer of 1,200 acres of land at Kattupalli, north of Chennai port in Tamil Nadu. He established a yard there and the state’s industry arm, Tamil Nadu Industrial Development Corporation (Tidco), took a three percent stake in L&T Shipbuilding Ltd.

Facilities at the shipyard would enable L&T to qualify for the substantially large contracts that Naik and his colleagues were angling for. They envisioned building Corvettes, destroyers and submarines for the Navy, and fast interceptor boats for the Coast Guard. L&T was already doing significant amount of work (fabrication and ship-building) at its other (smaller) yard at Hazira in Gujarat, but the company wanted to build competence in ship design, manufacturing and integration. “We wanted to make sure we had everything needed to qualify for the [big] contracts,” says Naik.

MV Kotwal, president of L&T’s heavy engineering division and a director on its board, has headed the company’s defence and nuclear business for many years now. The soft-spoken technocrat, who started his career as a junior engineer at L&T, leads what is perhaps the most cutting-edge work in the company. For instance, Kotwal’s division has built the pressure hull, a critical component, for India’s first nuclear-powered submarine, INS Arihant. Only five other countries (all permanent members of the United Nations Security Council) have the capability to build a nuclear sub.

Other work done by his division includes building weapon-launching systems for anti-submarine warfare and missile launchers, and working with ‘exotic’ material and composites for rockets and aerospace applications. India’s only shop capable of making heavy forgings used to produce nuclear reactors is part of this group. “L&T’s edge over competition comes from our design capability and expertise in project management,” Kotwal points out.

Anticipating work from the Navy, L&T has about 35 former naval officers on its rolls. Some are from the elite Directorate of Naval Design which was set up to build and indigenise the Indian naval fleet others specialise in ship and submarine maintenance and repair work.

Kotwal says he was convinced about the potential for big business from Indian defence. For good reason: As the world’s largest arms importer, analysts estimate that India will spend about $250 billion in the next 10 years to buy arms and equipment. Much of this will aim to narrow the gap with China, which spends $120 billion a year on defence (India has budgeted $39 billion for this year’s defence spend).

Post 2007, Kotwal and Naik got the L&T board to approve two of the largest investments the company had ever made in single projects. Close to Rs 1,900 crore was ploughed into Kattupalli to build a shipyard aimed entirely at meeting orders from the defence department. The yard was fitted with a monster shiplift (also built by L&T) designed to lift vessels of up to 18,000 tonnes. The second project was a joint venture with the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL, which has a 26 percent stake) to produce special steels and heavy forgings at Hazira. Some of these capabilities would be used for defence contracts. Kotwal felt that L&T was well-placed to operate this unique facility which was not only good business but also highly strategic for India. By then it was clear that the country was going ahead with nuclear power and depending on foreign suppliers entirely was not a wise option. L&T has invested about Rs 1,700 crore in this project. By 2012, both these facilities were ready. But orders seemed to have evaporated.

Treading water

The inertia of the lost decade made orders peter out. Today, not even one of the 24 submarines has been inducted, resulting in one of the most critical operational military gaps in India’s stealth capability in the seas. The construction of the first six submarines (Scorpenes), being handled by PSUs, is running four years behind schedule. The big ship contracts were all granted to government-owned shipyards by nomination.

In 2008, Naik made a two-hour presentation to then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh on the need to expedite Project-75(I). But all urging and negotiating proved futile. Nothing could budge the government. Kotwal and his team also lost an Indian Navy order to Pipavav Defence for manufacture of offshore patrol vessels (OPV).

Naval projects were not all that were stuck or stymied.

In 2009, L&T was in the race to supply Future Infantry Combat Vehicles to the army—this is a lightly-armoured, off-road vehicle which can zoom over sand dunes and cross small rivers. The defence ministry had invited three private companies and the Ordnance Factories Board to put in bids to supply 2,600 of these vehicles. The order was estimated to be worth $10 billion. The move was hailed as path-breaking and there was much excitement among Indian companies which began tying up with foreign partners to start the design work. Apart from L&T, other bidders were Mahindra & Mahindra and the Tata Group. But the ministry suddenly withdrew the letter of intent in 2012. No reasons were given and the deal came to a standstill.

Clearly, the meter is ticking for L&T. Losses on ship-building have been close to an accumulated Rs 900 crore in the past two years. On the nuclear forgings business, it is losing Rs 300 crore per year. Here, says Kotwal, the issue hinges on India’s Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act, 2010. “The law asks equipment-suppliers to nuclear plants to take undefined, unlimited risks. This is not tenable for any supplier. We should conform to international practice, where the plant’s operator takes on the liability,” he says. NPCIL sources say the law is being reviewed as no international supplier is willing to work within the current law.

Even beyond the defence dilemma, some analysts covering L&T are not too pleased with its performance. The last few years have been tough and margins have fallen. The core infrastructure and hydrocarbon businesses have been under pressure. Akshay Soni, analyst for Morgan Stanley Research, says L&T’s increasing risk and complexity is a matter of concern. But investors don’t seem to be overly worried. The L&T stock price on the BSE closed at Rs 1,607 on September 9, up 99 percent from the same day last year. In comparison, the Sensex rose 36 percent in the same period.

Hope of future orders

When Forbes India visited Kattupalli, the shipyard was busy, albeit with civilian work. In the absence of sufficient defence contracts, Kotwal and his team are pitching aggressively to build commercial vessels, particularly for the oil and gas industry. Six such platform supply vessels are now being built at the yard as part of a $154 million contract from Qatari company Halul Offshore Services. L&T won this deal against global competition last year. The yard also sees ship repair work from the navy and shipping companies. More work could come from India’s plan to build LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas) tankers.

A large contract for which tenders have just been issued is to build LNG tankers for GAIL (Gas Authority of India Limited). The tender is for nine ships which will carry shale gas from the US to India. Three of these are to be built in India. The tenders are offered to shipping lines, but L&T hopes to get a chunk of this business by tying up with them.

“Our investments are ahead of time, but they will surely pay for us,” says Kotwal. His team is currently in South Korea, trying to evaluate its technology options for the tankers. (The Koreans use membrane-technology for their LNG ships this is cheaper than the Moss technology developed by Norwegian company Moss Maritime.) An average LNG tanker costs around $200 million and Chinese shipyards are leading the push for business that will arise out of gas exports from the US. L&T already builds commercial ships for export, and hopes to up the game by eventually moving into larger, more sophisticated vessels.

Naval analyst Commodore

(Retd) Ranjit Rai has been following L&T’s progress over the years. He says, “It is India’s equivalent of Bechtel (US engineering multinational) and has excellent facilities. It is the only one that had the capability to work with Titanium steel and build the nose-cone and stern shafting for the Arihant.” L&T’s ability for modular construction allows them to work on several ships simultaneously, he points out. The navy has 44 more ship orders in the pipeline and the private sector is well-placed to get a chunk of this, he adds.

But how long will the wait be? When asked if he will sell out and exit the business if the order situation does not improve, Naik’s response is immediate. “L&T are builders to the nation,” he says. “We have built a national treasure, I cannot let go of it.” And he is hopeful of change with a new government at the helm.

His optimism may not be misplaced. When Forbes India met him, reports were coming in of plans to build the second line of submarines in India. Another big contract, to buy $2.5 billion worth of helicopters from the US, was cleared last month. This could lead to meaningful offset work for L&T.

However, Indian industry has often complained that global arms/equipment suppliers like Boeing, Lockheed Martin and others have not been offering any high-end work to Indian companies, as is envisaged in the offset policies.

It also helps that Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Defence Minister Arun Jaitley have been outspoken in favour of ‘make’ or ‘buy and make’ deals for defence equipment. The Indian industry hopes that it can also export defence equipment to smaller countries. There are other issues to contend with, though. Amit Cowshish, former financial advisor (acquisition), defence ministry, and now a distinguished fellow at the Indian Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, warns that the acquisition process in the defence forces is, by nature, time-consuming. For big contracts, the forces take at least a couple of years even to prepare the RFPs (requests for proposal).

“Comparing the process to China is unfair because the political system there is completely different,” he says. “For instance, a bulk of China’s arms exports is to Pakistan. Considering our geopolitical stand, can our government list out a dozen countries we can formally okay arms exports to? Can we export arms to Sri Lanka or to Nepal?”

Further, Naik worries about the “execution-side” of the government not being in place. Jaitley has too much on his plate—how much can he do with the finance ministry, ministry of corporate affairs and the defence ministry under him? They are like three oceans, Naik points out, saying he wishes that the government was run like a business.

“We need a strong man who heads the defence ministry to take decisions quickly. The government needs a big boost in capabilities at various levels. Expectations are very high and the danger is that disappointment can come very quickly too,’’ he says.

In effect, it all boils down to the man in charge again. The defence minister holds the key.

First Published: Sep 29, 2014, 06:18

Subscribe Now