Karl Slym has a Fix for the ailing Tata Motors

Karl Slym wants to change the way Tata Motors makes and sells its cars. But the cars he has don't sell; and his idea of those that will should take at least two years to hit the market

Karl Slym

Age : 50

Career : Started at Toyota as senior manager spent more than 25 years in GM across roles and geographies, including seven years as head of GM’s India operations. Joined Tata Motors in October 2012.

Education : MSc in business administration, Stanford University

Interests : Music, Bollywood, cricket and travelling

It was October 2012. Karl Slym, the new managing director of Tata Motors, had just joined office. And he was keen to get a pulse of the organisation quickly. Slym asked Tapan Ghosh, regional manager (west) in the passenger vehicles division, to fix up a meeting with Kasturi Wasan, owner of Wasan Motors, one of the oldest and largest dealers of Tata cars in the country. The meeting was fixed at Wasan’s Tata-Fiat dealership in Chembur, Mumbai, at 5 pm. Slym walked into Wasan’s sprawling fourth floor office, overlooking the Sion-Trombay road, with two of his colleagues—Prashant Fadnavis, head of marketing services, and Ghosh. After exchanging pleasantries, Slym got down to business, “So Mr Wasan, how is it going?”

Wasan had been waiting for this opportunity for a long time and he didn’t hold back. Sales had plummeted to 225 units per month compared to an average of 900 units in 2008-09. Despite all kinds of marketing pushes—buy a Nano with a credit card, exchange your old motorcycle for a Nano—the car had remained a non-starter. It was the same story with the Manza, the Indica, the Safari and the Aria. There were hardly any footfalls in his showroom and his sales staff was demoralised.

“With these issues, I will not have enough money to even pay salaries to my staff. In fact, I have been thinking of closing this dealership because I have been making losses for the last two years,” he told Slym.

The new MD heard him out patiently. At the end of the meeting, which lasted about 90 minutes, Slym said, “No, Mr Wasan, don’t give up. Give me 90 days and I will do something. If you still think your dealership is not viable, then you are free to go.”

Slym’s promise of 90 days ended in December 2012. It is now actually more than 180 days but Wasan hasn’t heard from him. Ghosh has since quit to join Hyundai. According to sources, in the last financial year Wasan’s Tata dealership made a loss of about Rs 6 crore. This March, he sold only 70 units. Now he is seriously contemplating pulling the plug. He won’t be the only one to have done that. In the last two years, Tata Motors has lost three large dealers in Mumbai, one in Pune, one in Chandigarh, two in Hyderabad and two in Delhi.

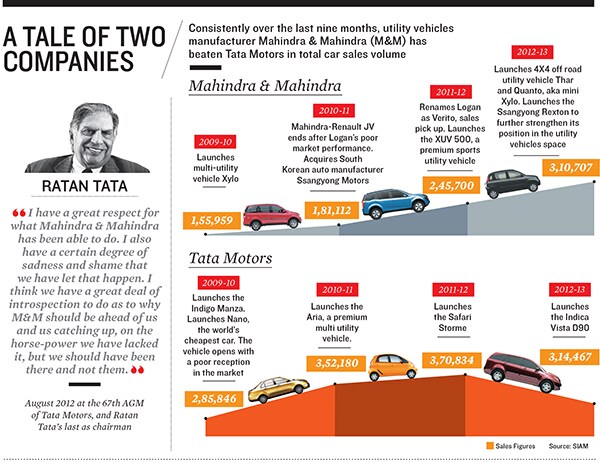

Today Tata Motors’ domestic car business is on a sticky wicket. Sales for FY2013 dropped by almost 29.2 percent to 2,22,112 units from 3,13,710 units in FY2012. In the December quarter, the standalone business posted a loss of Rs 458 crore. Analysts are expecting another loss in the current quarter. On the products front, in 2012-13 the Nano has utilised only 20 percent of its production capacity of 2,50,000 units at Sanand, Gujarat. Almost all of Tata’s other vehicles (Indica Vista, Manza, Safari, Sumo Grande, Aria) have been beaten in their respective segments by local and global competitors.

A former Tata Motors senior official, who spent more than a decade at the company and spoke on condition of anonymity, says this is the result of lack of focus, poor allocation of resources and narrow vision for the car business. “In the last five years, there were just too many things vying for attention. First, there was making the Nano itself. Then Singur and taking the plant to Sanand. Then fires in the Nano. Then Jaguar Land Rover. All of this meant that everything that had been planned for the car business was getting postponed. And we never had enough money to invest in building a pipeline for our existing brands,” he says.

Of course, Cyrus P Mistry, the chairman of Tata Sons, has taken notice. He asked the organisation to buckle up in his Lake House address to employees on April 1. “The last four years witnessed fierce competition in the passenger car market, with the entry of seven new global manufacturers and the introduction of 150 new models. The commercial vehicle segment too faced challenges with the entry of new players like Bharat Benz,” he said. “It is time to meet them and beat them in their backyard.” In his meetings with the top management, Mistry has been pushing towards making the car business profitable, developing “futuristic products that are truly world class” and to draw lessons from the turnaround of Jaguar Land Rover.

Lord Kumar Bhattacharyya, founder and chairman of the Warwick Manufacturing group, who was part of the five-member search committee that selected Mistry as Ratan Tata"s successor believe Mistry will do he can to make the company a success. “Let me tell you, Cyrus is a very forensic man. He has got a tremendous mind. And he will not go on a whim or fashion, he will do whatever is right for the company as a business. And it has to make money. Cyrus is not going to tolerate any weaknesses in the organisation. Car companies cost a lot of money, they should not only be designed well but also made well and sold well.”

Lord Bhattacharyya should know. He has seen the company’s steep decline from close quarters and believes that Ratan Tata’s vision for the car business was let down by the senior management at the company. “Ratan, as far as cars are concerned, it is in his blood. But he is not going to go and sell cars. It is up to Tata Motors to sell. Somehow, Tata Motors lost touch with the market. They had an iconic car like Nano, which Ratan had produced but it never got the due respect in marketing. If it was in any other country, it would have been a great success,” he says.

The Problem

The story of Tata Motors is also the story of two companies: Tata Motors India and Jaguar Land Rover (JLR). Its current state of affairs reflects in its financial performance. Ralf Speth is the man leading the charge at JLR. During his tenure, the company has grown dramatically. In the 12 months to March 31, 2012, JLR generated profit after tax of £1.4 billion compared to £1 billion in the year ending March 31, 2011. The company’s revenue increased from £9.8 billion in March 2011 to £13.5 billion in March 2012. In 2012, the company sold 3,57,773 vehicles, up 30 percent over 2011. Today, almost 90 percent of Tata Motors’ profits and more than 70 percent of its turnover comes from JLR.

Ralf Speth is the man leading the charge at JLR. During his tenure, the company has grown dramatically. In the 12 months to March 31, 2012, JLR generated profit after tax of £1.4 billion compared to £1 billion in the year ending March 31, 2011. The company’s revenue increased from £9.8 billion in March 2011 to £13.5 billion in March 2012. In 2012, the company sold 3,57,773 vehicles, up 30 percent over 2011. Today, almost 90 percent of Tata Motors’ profits and more than 70 percent of its turnover comes from JLR.

Now contrast JLR’s performance with Tata Motors’ Indian operations. While the company does not release separate numbers for its car and commercial vehicles business, Tata Motors’ net profit from its Indian operations has dropped by almost 40 percent in the last five years. The company reported a net profit (standalone) of Rs 1,242 crore in March 2012 compared to Rs 2,029 crore in March 2008. Its return on capital employed (ROCE) from its India (standalone) operations has dropped from 18.96 percent in March 2008 to 10.36 percent in March 2012. The company’s standalone net cash from operating activities has dropped from Rs 6,154 crore in March 2008 to Rs 3,653 crore in March 2012.

Jinesh Gandhi, equity research analyst at Motilal Oswal Securities, says, “Right now, the private vehicle [car] business is being funded by the commercial vehicles [trucks and buses] business and contributions from JLR. There are no restrictions in terms of movement of cash across divisions. But going forward it is not going to be that easy. The commercial vehicles business is going through a cyclical downturn which we hope will make some recovery next year. And JLR has its own investment commitments of about £2.5 billion next year and the year after that. So free cash flow will be curtailed.”

This is where Karl Slym’s million-dollar assignment comes in. Can he change the fortunes of this division of Tata Motors? He’s confident he can.

Losing Touch with the Market

But first, Tata Motors must get back in touch with the market. Let’s understand how it lost touch in the first place.

There’s the story of Safari18. In early 2006, the Safari18 project was initiated at the Engineering and Research Centre at the Tata Motors plant in Pune. The old Safari had been Tata’s workhorse in the sports utility vehicle (SUV) segment for over seven years and it urgently needed a refresh—the ‘18’ stood for 18 months. By industry standards, that’s a healthy target. Except that it was never achieved. Instead, it took Tata Motors six years to finally get the vehicle out and the new Safari Storme was launched only in October 2012. Total money spent: About Rs 400 crore.

In the automotive business and especially in a cut-throat market like India, a mistake like this can prove to be quite costly. In the last six years, sales of utility vehicles in India have skyrocketed. The market has grown by almost four times to more than 5,53,000 units per year. In this same period, utility vehicles manufacturer Mahindra & Mahindra launched three completely new vehicles (Xylo, XUV 500 and Quanto) while refreshing its existing portfolio (Bolero and Thar). Even India’s largest car maker Maruti Suzuki, which was primarily a small car manufacturer, launched a hugely successful UV from scratch called Ertiga. There’s also Renault’s big bang entry into the SUV space with Duster, which has captured the fancy of Indian customers. Who was caught napping? Tata Motors. In a segment in which it enjoyed pole position just a few years back.

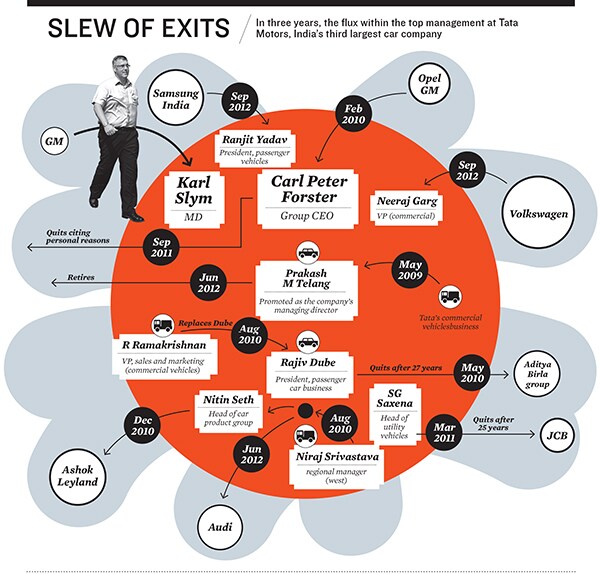

Then there is another way to lose ground—a dramatic flux in the top management team. Come to think of it, Karl Slym, who joined office in October 2012, is the only CEO (for its car business) that Tata Motors has had in a long time.

It all started with the Nano debacle and the exit of Rajiv Dube as head of the passenger car business in May 2010. This was soon after Carl Peter Forster came in as the global CEO of the company. Forster brought in Ralf Speth to head JLR. Prakash Telang was elevated from head of commercial vehicles business to MD, India operations. R Ramakrishnan, the champion of Tata’s successful takeover of South Korea’s Daewoo Motors in the commercial vehicles business, was air-lifted to take over Dube’s role and began reporting to Telang.

Soon, it was head of car product group Nitin Seth’s turn to leave and join Ashok Leyland. Till date, Seth has poached about 34 people from his former employer. Seth was soon replaced by Niraj Srivastava, regional manager (west) of the commercial vehicles business. Around the time of Seth’s exit, SG Saxena, head of Tata’s utility vehicles business, also quit to join JCB. In May 2011, Forster quit Tata Motors citing personal reasons. Telang retired in 2012. Srivastava quit last year to join Audi India.

So, for about three years, Tata’s car business was run by people who had made their career in the commercial vehicles business. It is not a surprise then that consultants believe that Tata’s passenger vehicle business has been run just like its commercial vehicles business.

“Look at their product refresh cycles. While competition has added products one after the other, Tata Motors must have used all the alphabets in the English language to launch one version after another of their old cars. That’s how you sell trucks not cars,” says a senior automotive consultant who did not want to be quoted.A jolly man with an unmistakable sense of humour, Slym gets a bit serious when discussing what really went wrong at Tata Motors. Slym spent the first three months of his tenure meeting dealers, suppliers, customers and employees of the company. What he came back with in the shape of a SWOT analysis wasn’t very encouraging. “The worst thing was our perception in the market as a passenger car maker. Our market, brand, quality—whatever you want to say—as perception in the marketplace is not as good as we would like it to be. I think the label was earned, it didn’t come from anywhere,” he says.

A car is an aspirational purchase. A Tata vehicle is far from that. The connotations associated with it are ‘value for money’ and ‘taxi’. Almost all of Tata’s vehicles—Indica, Indigo, Sumo—are predominantly bought by fleet taxi owners. “Which is a good endorsement,” says Slym, “Because fleet buyers buy stuff that is good value for money and endurance. However, an overemphasis on fleet turns away the personal buyer. So this is the balance between what do you want as fleet and what do you want from a customer as aspiration, does he aspire to buy that car which he thinks as a taxi? So I think it is important for us to now have differentiation in our products.”

This problem manifests itself at the point of sale. Harsh Vardhan, a former JWT executive, is an independent brand consultant who has worked closely with Tata Motors’ dealer subsidiary Concorde Motors. He spent months speaking to prospective customers and studying their buying experiences. What did he find? “There are serious image confrontations at the point of sale. Everybody is on the same floor—the fleet taxi owner, the driver of a Sumo and this executive with his wife looking at the Indica. It is a bit of a let-down of the executive’s image which makes him think this car is not for me but for taxis,” he says.

Slym found another vexing issue. What does a Tata car stand for? “If Maruti launched something that’s got excellent fuel economy, the emphasis is on the fuel economy. So, therefore, you have to focus on your strengths. The emphasis has got to be on the car. And I think we have had a little bit of disconnect between the company and the customer,” he says.

Tata’s brand positioning has been at best confusing—‘more car per car’, ‘club class’, ‘reclaim your life’, ‘the real SUV’ and ‘a class apart’ are just a few examples. Scratch a bit more and one can find a more serious problem. Traditionally, there were three planks on which Tata Motors sold its vehicles: 1. Operating economics, aka diesel. 2. Cheap acquisition price. 3. Space.

“Today we have lost all three. Our dominance as the only diesel player is long gone. Across all our segments, both multinationals and Indian companies have vehicles which are competitively priced. And the market has moved from driving around large families to self-drive vehicles. There as a brand we have lost relevance,” says a Tata Motors official who did not want to be quoted.

Add to the above issues, the far larger problem where Tata’s product development machinery has failed to regularly churn out new products. Which leaves them today with a portfolio that could well have been from the early half of last decade. When was the last time Tata Motors launched a completely new vehicle? Slym adds, “This year, how many cars have seen growth? Only new cars, none of the old cars. When was my last new car launch? The Aria. Which was two years ago, so it has been a while. So that’s not in line with keeping your name in line with the minds of people. It has been a problem for us in identifying where and when we want our products.”

While Tata Motors does not release standalone results for its car business, experts estimate the company has invested more than Rs 5,000 crore in the Nano project. “Nano is not the whole and soul of your strategy. But for political motivations within the company, there was never a vision that we should have a portfolio of cars. Some of that will be value for money. Others which will be cool, young and yuppie. In that same space Maruti has seven brands, Hyundai has three while Tata has just one—the Indica. How do you expect the company to compete?” adds the former Tata Motors official quoted earlier.

Analysts are also sceptical. Motilal Oswal Securities’ Jinesh Gandhi says, “The new management has enough understanding and experience of the passenger vehicles business. But it will take at least three years to arrest the current situation. Given that the car business is a cash guzzler, it will require investments in new products and marketing. Most of that contribution will come from Jaguar Land Rover and the commercial vehicles business.”  The Containment Strategy

The Containment Strategy

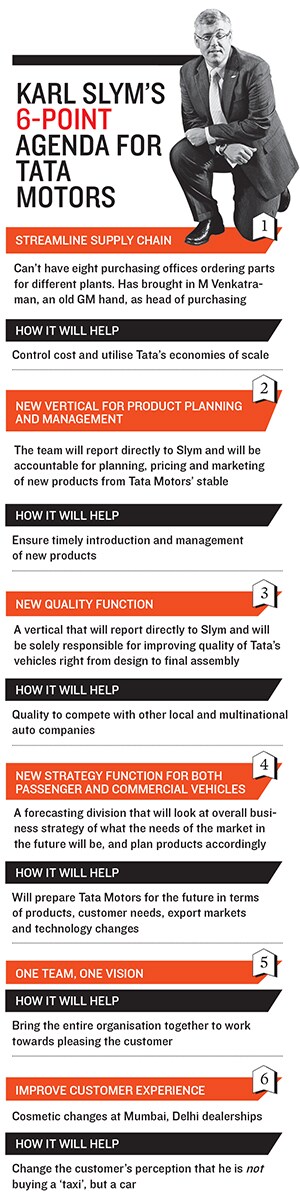

On December 18, 2012, Slym got together the top 82 leaders of Tata Motors to roll out what he calls his ‘One Team, One Vision’ plan. It has a fairly obvious message: Let’s focus on the customer. Quite often large companies take this route of identifying a common vision document which everybody can relate to. Slym has done the same and he is pretty kicked about the result. “I was at Dharwad the other day and I asked the team at our all-employee meeting and they know the mission, they know the vision, they know the values, they are motivated, so that to me is a good sign that the people can articulate it and we have done a good job of rolling it out,” says Slym.

The man is a firm believer in the principal that an organisation should be able to maintain a healthy balance between short- and long-term objectives. Something that he found amiss at Tata Motors. “I think there are two words that sometimes don’t translate well together—there’s containment and countermeasure. Countermeasure stops the problem occurring at the root and containment stops it from getting out to wherever it is supposed to go. So I think there is a lot of containment things that we are doing at the moment to be able to protect while we put the countermeasure in place,” Slym adds.

His containment strategies can be summed up thus: Building an organisational structure that has accountability, fixing product planning, emphasis on quality and a strategy function that can plan for the future.

He’s begun with tweaking the supply chain first. “We didn’t have a single purchasing organisation which I think was a huge shortcoming for us because we miss out on the benefits of our scale, we confuse a lot of things that way, so we have now got M Venkatraman as head of purchasing.

Instead of having eight purchasing centres and buying things for specific plants, we have centralised it,” he adds. Venkatraman is an old GM hand and his appointment is in line with the top-level changes that have accompanied Slym’s arrival at Tata Motors. In October 2012, Ranjit Yadav, country head of Samsung India’s mobile & IT business, was brought in to replace R Ramakrishnan as president of the car business. Neeraj Garg, former director of sales and marketing at Volkswagen India, was appointed as vice president.

To fix issues in product planning and product management, Slym has changed their mandate and also ensured that the team reports directly to him. “We didn’t have a programme planning organisation, we had a programme monitoring or managing unit, as a result of which some of our vehicles have not been necessarily on time as we would like them,” he says.

It is a big learning from the Aria debacle. “People in the beginning have to identify what’s happening in the world today and the future. And then the customers’ expectations three years ahead is designed and engineered into the car and we don’t lose anything along the way and we don’t let three years become six years either,” Slym says.

If that were the case, the Aria should have been pitted right against Toyota Innova. He adds, “It looks quite similar and it sells quite some volumes in that area. There you go. But the Innova is Rs 9.95 lakh and the Aria was launched at Rs 14.5 lakh. So why do I pay Rs 5 lakh more than the Innova if we are looking at the same customer? You don’t. So that’s where we get back to the disconnect with the customer, not just at the point of sale.”

Poor quality has been a perennial issue with Tata’s passenger vehicles. Slym is attempting to fix that and has created a team under SB Bowankar (who will also report directly to him), whose sole job is to focus on improving quality. “You can’t expect the manufacturing guy to take care of quality. You have got to have the supplier delivering the right thing which is from our design and engineering etc, so we now have a quality function standalone reporting to me but looking at the full piece of quality from the very early design,” he adds.

Last but not the least is strategy. “I have been internally critical of the fact that in some places we haven’t got products where if we want to be a volume manufacturer we have got to have products. So we now have a strategy group that not only looks at products but also looks at our overall business strategy as well to make sure we have got binoculars on, as I call it, to see not tomorrow, 2013 or 2014 but what will happen in 2016, 17, 18 and how we are preparing for that. Whether that be a product opportunity, a country opportunity even legislation or fuel type and all those kind of things,” he says.

Most of these measures look fantastic on paper. But the question is how long before they can translate into something real on the ground? Slym knows this bit of the story thanks to the promises he has made to dealers. But how long will it take?

Slym says, “It is not just that piece on quality. It is also everything else. Some things have happened already but you know how long a vehicle development cycle takes, so therefore, a new vehicle coming to market will be a number of years. So those kind of things coming into the market which is new, new, new vehicles with platforms and things like that will be a number of years.” Is this going to be a case of too little, too late?

First Published: May 15, 2013, 06:09

Subscribe Now