India Inc Needs to Wake Up to its Social Responsibilities

Profit cannot be the only purpose of business. Smart CEOs are realising that, taken in the right spirit, CSR has the capacity of making firms humane

On a recent Saturday morning at 9 am, Wipro Chairman Azim Premji walked into the JN Tata Auditorium at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore to hand out the Earthian awards to students from around the country. For over a decade Wipro has been advocating quality education in schools. Four years ago it added ecology to its social agenda. The Earthian awards, given to students for writing a paper on sustainability, is one way in which Wipro has been trying to build awareness about tackling environmental issues among the youth of this country.

The symbolism of the venue (IISc was set up with grants given by the Tatas) was hard to overlook. Premji has been a big admirer of the Tatas model of philanthropy. For over a decade now he has tried to push Wipro on a similar path by using the enormous resources of the company to solve a crucial social issue such as education.

After the awards Premji took some questions from the audience. A young schoolgirl, around 15 years of age, asked Premji to pick the most defining moments of his life. Premji chose two. The first moment, he said, was at the age of 21, when he realised how dependant he was on people around him (Premji had to take over his family business upon his father’s sudden death). And second, almost three decades later, in the year 1999-2000, when he had the epiphany that he must contribute to a social issue.

“The new world order needs three Es—economic growth, equitable society, and ecological sustainability,” wrote Premji in Wipro’s recent sustainability report. “We also believe that business must play a crucial role in making this happen. Government and civil society are equal stakeholders in this mission, but as a crucible of innovation, problem solving and value creation, the business sector is uniquely positioned to make a vital difference.”

The relationship between business and society has never been an easy one. In a country like India, where socialism has had a long history, it has been even more thorny. The mantle of being the protector, the provider belongs to the government, at least in the mind of the society. Business exists to make money. It is opportunistic. It is out to exploit. Can this thinking change? Can business and society find a way to talk to each other?

THE 2% DOCTRINE

The government certainly thinks so. The new Companies Bill has introduced a small measure that has the potential to change the way business and society engage with each other. The Bill recommends that companies earning a turnover of more than Rs 1,000 crore spend up to 2 percent of their average net profits (of past three years) on corporate social responsibility (CSR). The Bill makes reporting of spends on CSR mandatory in company balance sheets. In case the company is unable to spend 2 percent, it needs to explain why it has not been able to do so in a public document.

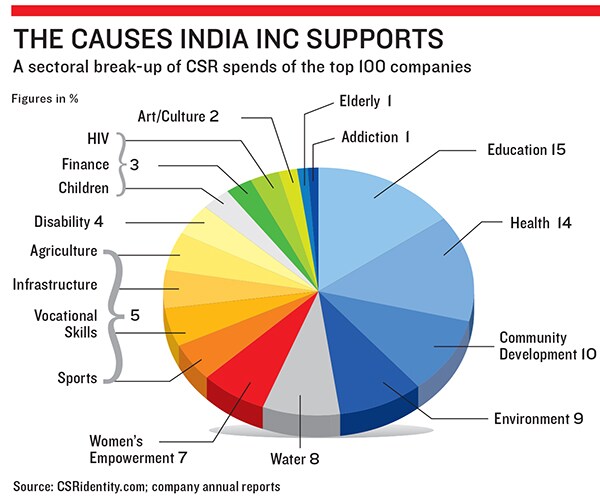

The government directive isn’t a knee-jerk reaction. Research done by CSRidentity.com shows that the top 100 companies in India are already spending upwards of Rs 1,750 crore every year on CSR. This sum would be approximately 1 percent of their net profits.

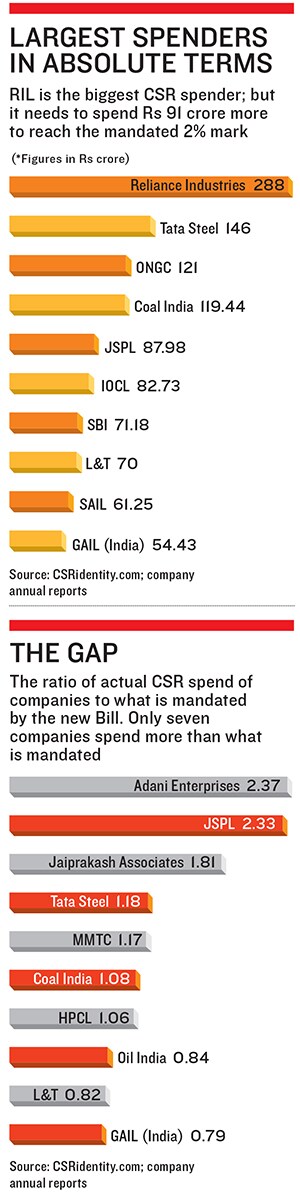

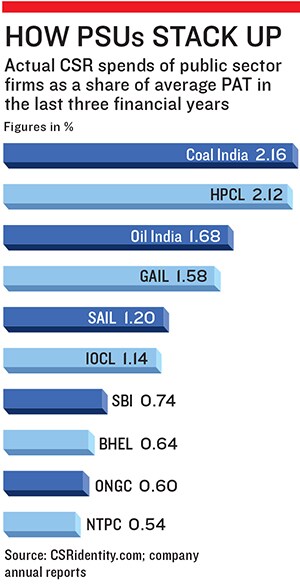

All that is now happening is that the random acts of kindness will become more focussed and hence impactful. Reliance Industries (RIL), State Bank of India (SBI), Tata Steel, National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC), Coal India (CIL) and Steel Authority of India (SAIL) are all spending more than Rs 100 crore each year on CSR. All these companies and some more are now experimenting and trying to make CSR an integral part of their business.

Now this entire move to get corporations to spend 2 percent of profits has critics. One of the detractors is Azim Premji himself who doesn’t think it is a good idea to force companies to spend money. This is a fair observation but the government isn’t really being coercive. There are no punitive measures as long as an independent director in the firm can explain the lack of spending. In some time most companies will be able to develop a CSR strategy simply because every year they will be publicly stating what they did or did not do.

SHAREHOLDER PLUS CAPITALISM

This is where the second objection comes in. Why should businesses be even forced to think about CSR? Businesses are basically set up to serve the shareholder. The shareholder can focus on social good on his personal money, but business, well, they aren’t real people with feelings so they should be left alone. “This is the shareholder money, how can the government decide how it should be spent. It is just plain wrong,” says Mohandas Pai, chairman, Manipal Education Global and the man instrumental in setting up Akshaya Patra, one of Asia’s largest mid-day meal programmes. In a scathing critique, Manish Sabharwal, chairman, Teamlease Services, wrote in The Economic Times on February 11, “Just like the checklist view of corporate governance did not lead to better companies, the checklist view of CSR will not create better corporate citizens.”

Both Pai and Sabharwal are right, but their views are anchored in the old paradigm of capitalism. That paradigm was over the day Lehman crashed. Nobody wants companies that give primacy to the shareholder when the going is good, but rush for taxpayer bailouts when the tide turns. The world wants its companies as real things talking to them, rather than be soul-less legal entities.

In the Anglo-Saxon world, which gave us capitalism, the thinking about how business connects to society has changed. Call it what you will—CSR, Conscious Capitalism, Double bottom-line, or Shared Value—smart CEOs know that Milton Friedman’s credo (the social responsibility of a business is to increase its profits) is pretty much dead today.Nobody illustrates the new thinking better than Paul Polman, CEO, Unilever, the Anglo-Dutch consumer goods company. In our special Forbes India Anniversary Edition in May last year, Polman wrote, “Since the 1980s we have all been worshipping at the altar of shareholder value. This is a doctrine which says that the principal purpose of business is to maximise returns to its investors. Although important, it cannot be the only purpose.”

In a separate article published in the Harvard Business Review, Polman estimates that in 2011 alone, climate change (droughts, floods, tsunami and earthquakes) and political crises because of non-sustainable growth cost Unilever over 200 million euros. He talked about studies, which said that the total profits of the consumer goods industry could be wiped out in about 30 years, if no action is taken.

In November 2010, Polman announced that Unilever was making social change a core part of its business model. He laid out an audacious new mission—the Sustainable Living Plan—under which by 2020 Unilever would double its revenue, while cutting its environmental impact in half. Managers in Unilever, from the CEO downward, have sustainability goals as part of their compensation.

Polman was honest enough to admit that he doesn’t have all the answers on how to tackle this issue, but by addressing it in such a public way and announcing a strategy he has at least managed to put a human face on it. “When people talk about a new code of ethics for business this is what we mean. For us it is a new form of business: One that focuses on the long term one that sees business as part of society, not separate from it one where companies seek to address the big social and environmental issues that confront humanity one where the needs of citizens and communities carry the same weight as the demands of shareholders,” wrote Polman in his signed column in Forbes India.

FOCUS, CONCENTRATE

Many Indian companies understand this. “Business is not conducted in a vacuum. We have to think of ourselves as responsible members of the society,” says Shikha Sharma, CEO, Axis Bank. Once this is clear the only thing left is to figure out the approach.

Don’t let anyone tell you that there is one Holy Grail approach to doing good. There isn’t. A company could either choose to back a few causes or it could back many. As long as the preparation is appropriate, both are possible.

At ICICI Bank, the board and the entire top team, led by CEO & MD Chanda Kochhar has been involved in a 10-year review of its CSR strategy for the past few months. A new ‘business plan’—just like the one the team would do for its regular business, incorporating the lessons that they’ve learnt—will now be presented to the board on March 31.

What the review revealed though is instructive. It found that their earlier strategy of going through intermediaries—either partnering NGOs or the government—wasn’t delivering clear benefits. “Most NGOs were unwilling to be accountable for the monies we gave them,” says K Ramkumar, executive director and head of operations and human resources at ICICI Bank.

What’s more, the impact was too scattered for them to find visible impact of spends. The story was no different when the ICICI Foundation chose to partner the government to build capabilities to raise the level of teaching in a local school before moving on to other projects. Yet once they stepped in to improve the curriculum and the quality of teaching, it almost seemed like “a case of abdication” by the state government. They would simply walk away, leaving it in the hands of the foundation for perpetuity. Besides, every time the government changed, or a supportive official was transferred, the new lot was simply not interested in picking up the threads. That has prompted ICICI Bank to reboot its CSR strategy. The crux of its new strategy will be to directly deliver benefits, instead of relying on an intermediary.

While the details are still being firmed up, to keep things simple, the bank has decided to pick two main areas where it believes it already has the internal competencies: Skill development and financial inclusion, says Kochhar.

Many other companies are following a similar approach, that is, look for a distinct fit with their core business. For instance, Tata Motors started a safe driving programme. ITC went in and realigned its supply chain to help farmers. HUL works with children in schools and mothers through health clinics to educate them about hygiene behaviour. Their aim is to change the hygiene behaviour of 1 billion consumers in Asia, Africa and Latin America by educating them about the benefits of hand washing at key times. Wipro has chosen education as its area of focus.

But even with this approach it is necessary to concentrate efforts. In 2011-12, a large public sector bank embarked on a big programme to distribute 13,600 water filters to as many schools. There is very little impact one such water filter will have in a school with hundreds of kids. It is as good as nothing. “Most corporate activity is very dilute and dispersed. It would make much more sense if it were targeted at a smaller geographic area,” says Sanjay Bapat, founder, CSRidentity.com.

FOR DIVERSITY, HAVE A ROADMAP

Hunkering down to support a big cause over the years may make practical sense, but not everyone seems to believe in sticking to the knitting. Some firms like Axis Bank have chosen to work across the CSR spectrum. C Babu Joseph, executive trustee and CEO, Axis Foundation, says that the bank believes that in India a variety of causes need to be funded. “If we stick to a few we will not be able to help others who may need it.” So they have funded education, livelihood, water conservation (as a means to ensure food security), and even an organisation that helps highway accident victims. “If we had a limited focus, we would have a limited impact and we would not be able to help more number of NGOs,” he says. Axis Foundation is quite clear in that it lays out a roadmap of CSR activity over a three to five year time frame. So in the past, it was education, but over the next three years or so, the Axis Foundation is concentrating on livelihood. “Today our big audacious goal is to generate 1 million sustainable livelihoods because right now livelihood enhancement is our focus area in CSR,” says Joseph. Over 80 percent of the foundation’s efforts are focussed on livelihoods now, the remaining goes to education and health.

Axis Foundation is quite clear in that it lays out a roadmap of CSR activity over a three to five year time frame. So in the past, it was education, but over the next three years or so, the Axis Foundation is concentrating on livelihood. “Today our big audacious goal is to generate 1 million sustainable livelihoods because right now livelihood enhancement is our focus area in CSR,” says Joseph. Over 80 percent of the foundation’s efforts are focussed on livelihoods now, the remaining goes to education and health.

Before it engages with an NGO, the Axis Foundation tells them that the foundation will invest in that cause for a period of three to five years, and at an appropriate time the NGO must look for new donors. “We help them in that process, but we make it clear that we will move away one day,” says Joseph.

Wipro does something similar for its flagship programme WATIS (Wipro Applying Thought in Schools). Over the last decade Wipro has touched 2,000 schools and 8 lakh students through WATIS.

WATIS works like a venture capital setup. A team of two full-time professionals runs this programme and works with a network of partners. Wipro provides funding, mentoring, and its brand power to help open up doors for the organisations. Funding is always tied to specific projects or longer-term programmes. It does not invest directly into the organisation. Today, it works with 30 partners—both for-profit and not-for-profit. It typically works with a partner organisation for three-five years till it finds that the organisation has reached scale and maturity.

There are no quick fixes when it comes to solving social issues. “To make a real difference in society, you often need to invest for a generation. A problem like malnutrition or adolescent marriage needs sustained attention for a minimum of five years,” says Dola Mohapatra, national director, ChildFund India, an international NGO working in India for 60 years. It has to be said though that Axis Bank and Wipro are doing something new and this needs to be understood better. The average tenure of CEOs and senior management is much lower today. There is no guarantee that once people change, the same cause will continue to receive attention. So it is better that even the NGOs get to know other corporations who will fund their cause. Till date, the Axis Foundation has worked with 63 NGOs. It is currently working with 23. “We believe that many NGOs have become better and more efficient organisations because of our association,” says Joseph.

MEASURE, IMPROVE, SCALE

It is in making NGOs more organised that corporations can really help. Most NGOs are run poorly. They often don’t measure what has worked. They can’t hire top talent and remain a rag-tag army out to change the world. Companies can help change that because they know how measuring, reporting and reviewing results can dramatically improve the quality of any effort.

Till now CSR has been an appendage simply because most corporations spend the money and don’t bother to find out the results of their intervention. They had little to tell their NGO partners who themselves did not have the ability to become bigger.

Shortly after she took over, Vidya Shah, who heads the Edelweiss Foundation, found that Edelweiss had committed 1 percent of its pre-tax profits to philanthropy, right from the start. Yet the giving to charity was done in an unstructured way largely based on the relationship with the head of the NGO. “We realised that we could add a lot of value as Edelweiss because we had the experience of working with young entrepreneurs,” says Shah. She now picks up expertise on areas such as strategy, HR, financial sustainability and systems and MIS (management information system) from the firm’s business vertical for their CSR strategy.

For instance, the firm has helped build an MIS platform for an NGO that managed remand homes across seven states. This helps the NGO capture data on the condition of every home while presenting the findings to the state, rather than rely on anecdotal evidence. It took two executives from Edelweiss’ in-house business solutions a year to build this low-cost platform.

Now companies realise that unless they work with the NGOs to improve monitoring and reporting, they will not be able to report success or failure and get wider support from their boards. “Every large corporate should have a CSR committee. Work has to be progressively done and monitored at the board level,” says MG Ramachandran, former chairman of Indian Oil, and now independent director on the board of ICICI Bank, where he heads the CSR committee.That’s beginning to change. One of the most important ways in which Wipro helps its partners is by creating an ecosystem and connecting partners to each other. For example, every year it organises a partner forum where all organisations in its network come together for a two-day offsite where they learn and network with each other. Many times Premji too attends these sessions. “We know that no amount of money we spend is enough for tackling a domain as large as education, but more than money we leverage our brand in making these partnerships work,” says Anurag Behar, chief sustainability officer, Wipro.

Premji is very clear that CSR should be seen as priority inside Wipro. So it is always one of his direct reports who has the responsibility for managing this function. He makes time for every important CSR event, and any opportunity that he gets to talk to an external audience—be it through his speeches at external events or newspaper write-ups—he chooses to talk on the quality of education in India. Every quarter he does a review of the CSR programme just as he does with his other business units.

Axis Foundation has always been very clear about reviewing its programmes. They do a baseline survey of the existing state of affair before they begin work in a particular area. Since the ‘before’ is known, the impact can be measured very clearly. “We have a quarterly review of all our projects. We present this to our board. If we feel that at the end of a year no visible impact is being felt, in spite of our best efforts, then we curtail our engagement with that project. This is rare and we usually persist,” says Joseph.

BUILD IT AND THEY SHALL PARTICIPATE

The effect of seeing a social programme yield verifiable results brings another advantage. Employees in a company want to be associated with something that is making an impact.

Take for instance how employees of Cognizant relate to CSR. Studies have shown that volunteering is a great way to build loyalty among the new generation of knowledge workers. In 2011, Deloitte conducted online interviews with 1,500 ‘millennials’ (ages 21 to 35) who work at companies with 1,000 or more employees that offer employee volunteer activities or programmes. The survey shows that millennials who frequently participate in their company’s employee volunteer activities are two times more likely to rate their corporate culture “very positive” as compared to those who rarely or never volunteer (56 percent vs 28 percent).

This is the kind of learning that Cognizant has put into practice through a corporate volunteering programme, Outreach. Since the programme was set up, 20,000 employees have volunteered and have spent a cumulative 2 lakh volunteering hours. Cognizant Outreach supports schools in the vicinity of the company campuses.

The programme works on a bottoms-up model, employees find schools and causes they want to support and present ideas to the Outreach council. Cognizant provides financial and administration support and sets aside a small budget. Archana Raghuram who heads the programme says that “we do not take up purely funding causes, so if it is only donating money for making a classroom, we don’t do it, employees have to volunteer for it as well.”

Employees take classes, provide career counselling, as well as teach computer science and English to students in these schools. In India, the programme has touched about 100 schools. The reason the programme works is because it has the attention from the highest levels. It was started at the behest of CEO Francisco D’Souza and directly reports to the president of the company, Gordon Coburn. Every quarter, the programme head submits a progress report to the CFO.

Now, this is the critical piece. For CSR projects to work, it has to evolve into a top management priority. At ICICI Bank, the new focus is on making some of its senior-most executives accountable for results in CSR to the board, rather than leave it to some lowly executive in a CSR department. Having people with the clout and influence to drive the agenda across the firm is a vital part of any CSR strategy.

Taken in the right spirit, CSR has the capacity of making firms humane. It can be the soul inside the profit-making machine that is the modern corporation. Thought of in those terms, 2 percent may be a small price to pay.

(Additional reporting by Prince Mathews Thomas)

First Published: Mar 18, 2013, 06:19

Subscribe Now