How To Destroy An Airline

Everything about Vijay Mallya is outsize: The fortune, the vintage cars, the yachts, the F1 team, the airline and yes, the ambition. And now, it seems inevitable, the fall.<br />[REPLUG: From Forbes I

It was said in a jocular vein. “You’re on the ventilator now. But the plug can’t be pulled because euthanasia is still illegal in the country.” The nervousness was palpable and titters followed the comment on a conference call that included Vijay Mallya and his most trusted aides. They were trying to figure a way out of the Rs 10,000 crore mess Kingfisher Airlines has accumulated in debts and unpaid bills over the years. Mallya, the chairman of the UB Group, laughed as well.

If there was any panic, it wasn’t evident in his voice. But those who’ve seen him from close quarters say he’s mellowed over the last one year. And that the man is fatigued because his back has been up against the wall for a long time now. It’s another matter altogether that he has no sympathy or sympathisers—all thanks to his “schizophrenic behaviour” as another aide puts it.

In mid-May this year, Mallya requisitioned staff from Kingfisher Airlines to go to Monaco to help with his ‘opening of the season’ party on his yacht moored at Monte Carlo. His party, now an annual tradition, was attended by the likes of Antonio Banderas and Formula One boss Bernie Ecclestone. The air hostesses kept their smiles on, as they saw their boss burn a few crores on a single night of high-jinks. They hadn’t been paid their salaries for the last four months.

But Vijay Mallya has it sorted out in his head. What he does in his personal life is nobody’s business. What he does in his professional dealings is all that ought to matter. His people though want him to read the writing on the wall. That his professional dealings aren’t the kind of stuff legends will be written about. Because if things continue the way they are, his son Siddhartha, for whom Vijay Mallya had created Kingfisher Airlines as a coming-of-age gift on his 18th birthday, will have no empire left to inherit.

In fact, they reminded him that it was just a few weeks ago, on June 21, that Hitesh Patel, executive vice president at Kingfisher Airlines, was at Lloyd’s of London, a 300-year-old insurance market run by hard-nosed brokers. Once upon a time, Lloyd’s used to insure ships in the slave trade. Now, they cover high-value assets like aircraft, space ships and oil rigs and they know a thing or two about pricing risk.

Patel’s plans to recapitalise Kingfisher sounded desperate. He knew that no airline can take off without an insurance cover. Which is why, even though the airline had defaulted on paying salaries, suppliers, fees to airport companies across the world and leasers from whom the airline had rented planes, it hadn’t on paying insurance premiums.

But as Patel went about his pitch, it was obvious to him the looks on the faces of the brokers were sceptical. How, they asked him, did Kingfisher plan to pay future premiums? Patel argued, over the next couple of months, the airline will prune its fleet to 35-odd. They raised their brows when he said Kingfisher has two investors lined up—the first a financial investor the second a strategic one. The airline was keen to go with the strategic partner, he said. And, he added, he expects the Indian government to ease its policies on foreign direct investment (FDI). That move, he told the audience, would give the airline a lifeline.

But as I write this story on July 2, things don’t look sanguine. While the folks at Lloyd’s, who’ve heard many tall tales during their careers, may come around to insuring Mallya’s fleet at a higher premium, his lenders may not be as kind. On July 5, before this copy reaches you, Mallya and team are scheduled to meet up with a committee of bankers at the State Bank of India’s (SBI) headquarters in Mumbai. They need to know how he plans to repay what he owes them.

When this committee met during the last quarter, representatives from SBI had asked Mallya to infuse fresh equity into the business, as this would signal his intent to get out of the mess.

But Mallya, aided by Ravi Nedungadi, his trusted lieutenant and the group’s chief financial officer (CFO), argued his way out using the FDI card. While the bankers said it was a “long shot”, they still decided to give him the benefit of doubt. Since then though, nothing has moved and the lenders are getting impatient. What they see is a man clinging to a disintegrating airline and destined to preside over the biggest bankruptcy in Indian business history.

On their part, the bankers are grappling with an animal of a kind they haven’t dealt with before. When they had to recover their monies from companies like Ispat, Essar Oil, or more recently Hindustan Construction Company (HCC), they lent against collateral in the form of the assets, and they could use that to arm-twist the promoters into paying up.

In Mallya’s case, what they have are intangibles—like the Kingfisher brand for instance. But this is uncharted territory for banks. There are not too many examples of making the most from brands that have been pledged—other than the occasional example like BPL. Then there is Mallya’s stake in his flagship United Breweries (UBL) and United Spirits (USL) that he had pledged as collateral. Even if these were put out in the open market, at current market prices, they would get just about Rs 150-200 crore. Add to all of this his personal assets like his many homes in various parts of the world. Tot up the net worth of all of this and it doesn’t add to the Rs 7,000 crore-odd the consortium would like to see back on their books.

Perhaps that explains why Mallya and Nedungadi always seem unflappable at these meetings. They don’t plead for time, nor do they sound desperate in their dealings. This, again, is nothing like what the battle-hardened bankers have seen in the past where promoters have practically gone down on their knees to protect their assets from liquidation.

That also explains why the consortium of lenders led by SBI and including Punjab National Bank, Central Bank of India and ICICI Bank has banded together, put the debts into a pool, and tried to figure the most viable way to get their money back.ICICI Bank has just exited this group. It sold the debt Mallya owed the bank to a global fund operated by SREI Infrastructure Finance. Such ‘vulture funds’ invest almost exclusively in companies that are almost bankrupt. The idea is to buy a distressed company’s shares at a very low price, hope to turn it around, and then sell it later for an extraordinarily large profit. In selling to SREI, ICICI Bank recovered the Rs 430 crore it had lent to the airline. On a mark-to-market basis (the value of the assets and liabilities as measured by the stock market) ICICI Bank took a hit. But on the face of a “long shot”, ICICI bankers reckon this was the best thing to do.

The number crunchers at public sector banks like SBI knew by late 2009 that lending to Mallya wasn’t an exercise in prudence, but found it difficult to refuse more debt. So they came up with a fairly ingenious solution. They started to write off the loans as NPAs, a term used by financial institutions for loans that stand the risk of default. They now had a valid reason to avoid lending—by the rulebook, you can’t lend to an NPA.

Which brings us back to what could possibly happen on July 5, when Mallya and Nedungadi meet the committee. Like in the past, deliberations will continue—the last meeting went on for over six hours—and the bankers will try to get back what is theirs. Blame it on a system that is unable to push through a liquidation or a change in management or on a wily entrepreneur who’s learnt the art of gaming the system and knows the only thing bankers have to go by is hope that he’ll put a do-able plan in place.

As a fall-back option, the banks have forced Mallya to pledge more shares in his liquor companies as collateral. So much so that almost 95 percent of his stake in United Spirits is now pledged with the banks. Despite that, the bankers’ hope hangs on a flimsy thread. As things stand, a good part of the Kingfisher fleet is grounded for lack of spares. Aircraft are being cannibalised to run the 13-14 planes that are operational. Many planes are parked in hangars across the world. Since the banks have stopped lending, group companies have been funding daily expenses. But the situation is now so grim, that those funds are drying up.

“The number of planes that continue to operate is likely to be pared down further and eventually it is expected to be a five-plane operation,” says a source at the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA). This is because five airplanes are the least needed by a company to retain its Airline Operator’s Licence. “This can bring down losses from Rs 10 crore a day to Rs 10 crore a month,” he adds.

But a lot of the airline’s infrastructure that Mallya built for a 100-aircraft global carrier remains intact. About 4,500 employees are still on its rolls, down from 7,000-odd a year ago. The impressive mock-up of the A330 plane, at the Qube, a corporate park near the Mumbai airport, is still in place.

As for the current operations, it takes most employees just a few hours a day to keep them running. The planning, revenue management and marketing departments, for instance, are full of people who have almost nothing to do. There is not much to sell and little long-term planning to do.

The airline was kicked out of International Air Transport Association’s (IATA) billing and settlement plan, and deals directly with the agents now.

A senior management person from Mallya’s team says the only reason his people are still there is because they haven’t been paid for five months now. They don’t have the option of walking out right now because if they do, there is a very real threat they’ll lose everything, including the money that ought to be credited to their provident fund accounts and other perquisites that were part of their original package.

AP Verma, deputy managing director and chief credit risk officer of SBI, says a phased closure of the airline is a possibility because the airline has shrunk to a point where its market share is just about 5 percent. But it is still not clear if lenders are willing to go to court and engage in a legal battle to extract their pound of flesh. The lenders have a popular refrain: There has never been an Rs 10,000 crore bankruptcy in India and who would benefit anyway?

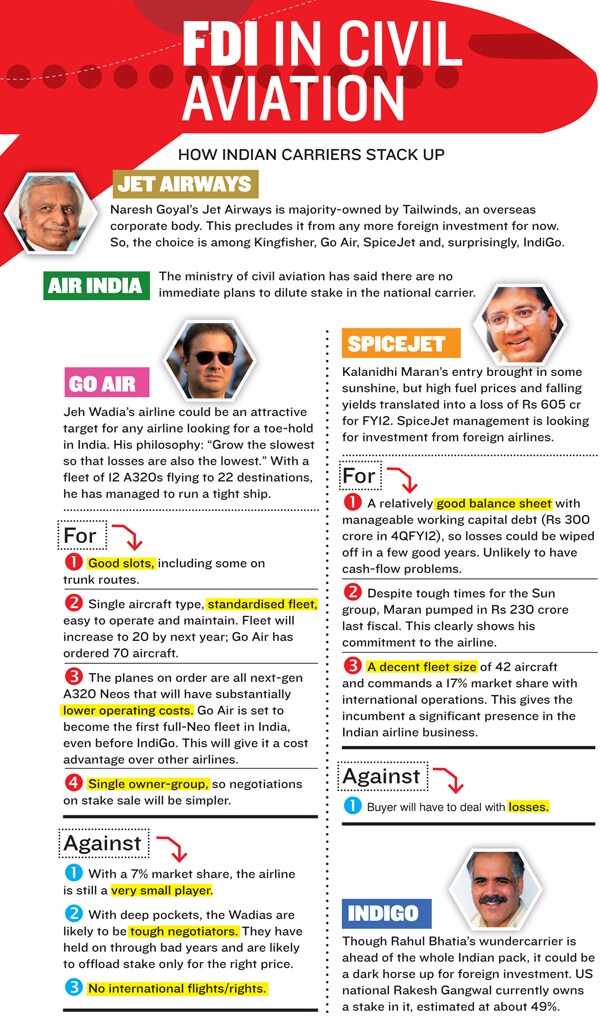

Not everyone is so sure. Jasdeep Singh, an airline analyst at Kotak Mahindra, an investment banking firm, argues it is impossible to service the airline’s liabilities with its existing operations. Foreign investors, he says, are unlikely to want to tangle with Kingfisher and will look for healthier airlines to invest in.

An aviation industry veteran who did not want to go on record says, “It is impossible to get any foreign airline to invest in Kingfisher. They can easily get much more from Spicejet, Go Air or anybody else for that matter. They won’t need more than $100 million to gain a toehold into India. Why take Mallya’s woes on their books?”

The view is corroborated by another London-based aviation analyst who declined to come on record. His arguments are that it will take at least $50 million to make the aircraft airworthy. So, he not only has to find ways to deal with the debt and outstanding payments, but also infuse capital to get this going. “Why on earth should Etihad or Qatar Airways want to touch him now?” he asks.

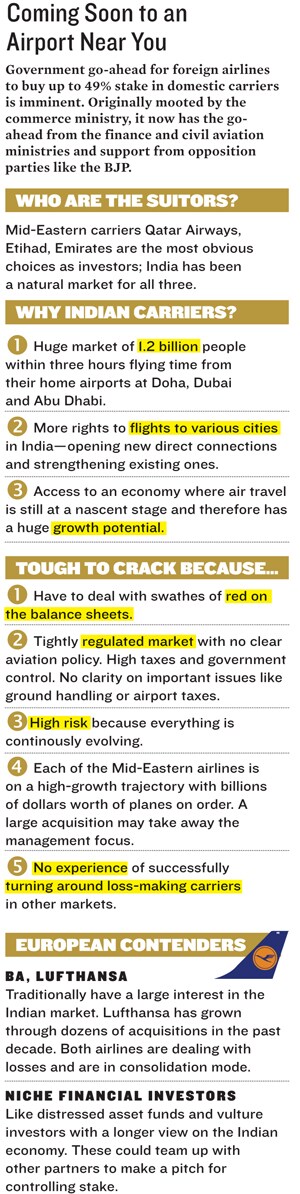

What it means is that, assuming FDI norms are eased and either of these airlines decides to pick a 49 percent stake in Kingfisher, they will in all likelihood ask for a 30-year (long-term) loan from banks and perhaps a five-ten year interest moratorium. Even if they squeeze out a concession from the banks, the new investors will still have to pump in at least $500 million. It simply doesn’t make business sense. As for Emirates, the airline owned by the royal family of Dubai, and one that Mallya has tried to woo in the past, CEO Tim Clark has clearly said they wouldn’t be interested.

Adding to Mallya’s misery is that arch rivals like Naresh Goyal of Jet Airways are frantically at work to ensure Kingfisher stays down. For instance, when Kingfisher was grounded in November last year and dozens of its flights were cancelled, Jet declined to honour tickets issued by Kingfisher. This, in spite of the fact that both airlines have an interline agreement in place. Instead, Jet Airways insisted Kingfisher pay full fares to accommodate stranded passengers. In markets like the US where airline bankruptcies aren’t rare, partner airlines usually step in to help.

It is also an open secret in the aviation business that Naresh Goyal has been lobbying for years to keep FDI into Indian aviation out. Until now, he’s been successful in staving the proposal off and in the process has denied his competition the much needed capital. “Naresh’s networking skills are legendary—particularly in the Middle East. He knows not only the top brass and the regulators in most countries, but also the sheikhs who own the airlines. He operates at various levels,” says a Jet insider who has worked with Goyal since the airline was launched. Mallya has reason to fear rivals like Goyal who have the ammunition to stop potential investors, including partners like Etihad and Qatar Airways from throwing a life-line.

That leaves Mallya with only two other options to raise funds and keep his airline business afloat.“The UB Group is now like the Roman empire, whose rulers struggled to manage it after expanding it,” says Santosh Kanekar, a liquor industry veteran-turned-consultant.

A little over three years ago, when we launched Forbes India in May 2009, we had written of how Kingfisher Airlines is teetering on the brink of disaster of how Mallya’s debts are mounting to frightening proportions of how he’s been lobbying hard with the finance ministry to ease FDI norms in the airline business of how his charm and influence convinced at least three public sector banks to loan him funds and of his now legendary rivalry with Naresh Goyal.

But back then, a senior investment banker dismissed our questions with a wave of his hand: “Vijay has always been up to his eyeballs in debt.” Ravi Jain, promoter of wine company Vallee de Vin, is somebody who’s seen Mallya from close quarters. He sounded equally nonchalant. “He is a man with many lives. He just needs to hang in there for some more time. Things will change when the market recovers,” he told us then. Their arguments sounded convincing and we concluded it was only a matter of time before he bounced back.

But three years down the line, there is little reason to believe Mallya wants to hold on to the airline business any more. By all indications, what he is doing right now is playing a game of brinksmanship. If he exercises the euthanasia option, creditors will surely come in to encash his personal guarantees, significantly eroding his own net worth. This includes banks and airport operators like Mumbai International Airport (MIAL). The latter has already initiated proceedings against him in the courts to recover its dues.

The hypothesis doing the rounds right now is that Mallya would ideally like to see someone else shut the airline down—either the government or the regulator. That way, he can claim he didn’t choose euthanasia, but was killed.

Now, if only somebody had the nerve to call his bluff!

(Additional reporting by Prince Mathews Thomas)

First Published: Jul 16, 2012, 06:11

Subscribe Now