“Oh God, what have I done?” wondered Pawan Goenka as he stood in front of Mahindra & Mahindra’s research and development (R&D) facility in Nashik, Maharashtra. It was October 13, 1993, his first day on the job as general manager (R&D). He had just returned from Detroit to India after a 14-year stint with General Motors, where he was managing the world’s then-largest carmaker’s engine design and development.

He had not expected M&M’s R&D infrastructure to match that of General Motors which, in the early 1990s, had an annual budget of $1 billion as well as a team of 20,000 engineers spread across multiple locations. But neither was Goenka prepared for the ground reality in Nashik. Consider that the research facility was merely a shed and had only 50 engineers. “I must admit that the starting point was a lot less than what I had imagined,” says Goenka, who is now executive director and president (automotive & farm equipment sectors) of the Mahindra group.

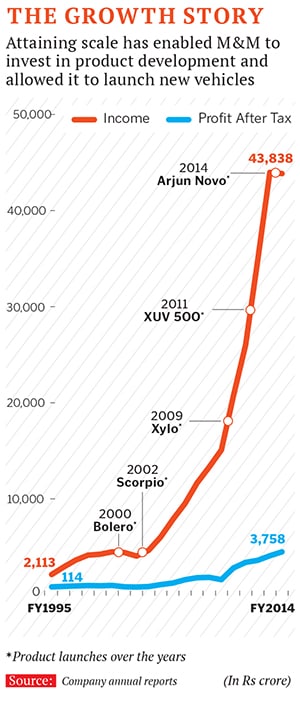

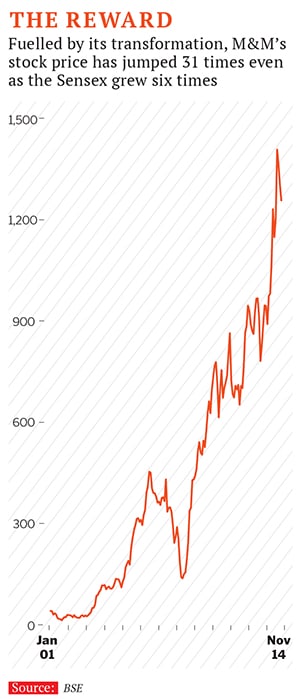

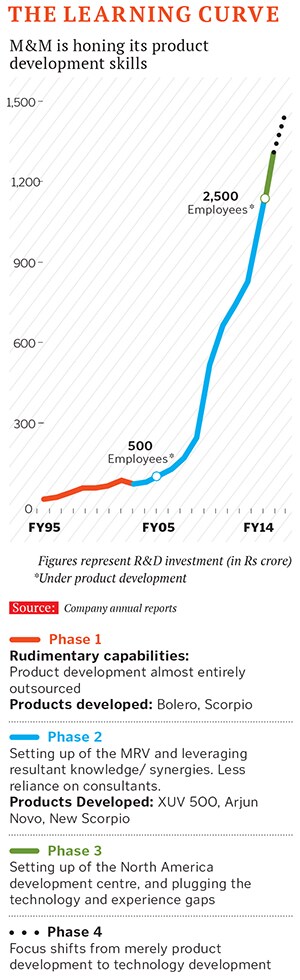

Twenty-one years on, M&M’s revenue has risen 25 times to Rs 43,838 crore from Rs 1,715 crore profits have gone up 55 times to Rs 3,758 crore from Rs 68 crore at the time. (The automotive and farm equipment business accounts for close to 66 percent of its overall revenues.) Also, the company has become the largest tractor manufacturer in the world apart from dominating the Indian SUV market in which almost every major global carmaker is fighting for a share. The most significant change has been this: Riding on strong product development abilities, M&M has managed to launch several successful products during this period.

Not that Goenka, then 38, could have predicted this outcome at the time. He was making his comeback to India with the broad plan of helping build a homegrown company. And his meeting with Anand Mahindra, then deputy managing director of M&M, had determined his journey. Mahindra told him how the country’s economic liberalisation and potential competition from global players had left M&M, a maker of pick-up trucks and jeeps for the rural market, with three options: Exit the automotive sector, become a licenced manufacturer for another company or develop own products. “We have chosen to develop our own products and compete with the world. I am looking for somebody to undertake this big task. You will have all the freedom. Just give me a product in a reasonable time,” Mahindra had told him.

Goenka, who had agreed, says it was “one of the very few decisions I have taken without looking at the spreadsheet”. And there has been little cause for regret. Because, despite the initial disadvantages, Goenka, with his single-minded focus on R&D and the full backing of his boss has steered the company on to the fast-track of growth—and established himself as an India Inc worthy.

The journey has not been devoid of uncertainty. To leapfrog limitations of scale, he had to keep drawing M&M into uncharted waters. Some of those moves—building Scorpio ground up when the company clearly lacked product development expertise, or setting up the Mahindra Research Valley when the country had a dearth of engineers with the required experience—could have sunk the company and culled his career. But for Goenka and Mahindra, fortune has so far favoured the brave.

And he is not finished yet. Goenka is now taking an even bigger risk by getting M&M to invest in automotive technology development—an area that has been the exclusive preserve of fat-pocketed global car majors. But he isn’t worried. Because, as Professor Vijay Govindarajan, Coxe Distinguished Professor of Management at Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business and an expert on innovation, puts it, “Leaders act with courage—making decisions without full information and in the face of enormous uncertainty and potential risk. They are not afraid to fail.”

THE IN-HOUSE GAMBIT

The transformation had a slow beginning. The availability of meagre resources in 1993-94 did not permit large-scale investment in research. Goenka, consequently, focussed on fixing what was possible—and necessary—to at least set the ball of product development rolling: For instance, various departments for computer-aided design as well as engineering and vehicle design were set up and staffed. The minimum requirement of infrastructure was built and people were trained.

This done, the first product to emerge from their newly-refurbished shop was a pick-up truck in 1997, followed by Bolero, an SUV, in 2000 which replaced their Armada, which had been launched in 1993. (M&M, which was established in 1948, had initially assembled multi-utility vehicles under a licence agreement with Willys Jeep. It continued its manufacturing activity through similar arrangements).

Though Bolero was the first product to be developed in-house, it used the Armada’s chassis, roof and door. Investment in it was kept low at Rs 30 crore. “Bolero’s success was beyond our wildest dreams. More than 14 years later, it still sells one lakh units a year,” points out Goenka. Bolero also bolstered—and widened—the company’s product range which had, thus far, included pick-up trucks and jeeps predominantly focussed on the rural markets.

By 1997, a year after Hyundai and Ford had set up operations in India, M&M began working on a new product. Aware of how urban India was transforming, and the manifold opportunities it presented, the company was “grappling with a major dilemma”, says Goenka. The quandary was: “Should we develop an all-new product or do a tinkering job like Bolero?”

It was not an easy decision. Building a new product from scratch would cost at least Rs 600 crore and at that time, M&M’s revenues stood at Rs 4,100 crore and profits at Rs 250 crore. It didn’t help that the company had no internal expertise—people, process or infrastructure—to develop the product. That apart, M&M had previously never launched a product for the urban market. “It was a make-or-break situation for M&M then. Competition was increasing. We had to take a bold call,” says Anand Mahindra, now chairman and managing director of the Mahindra group. And it did just that by deciding to develop a new vehicle. The product was Scorpio. “The decision to build the Scorpio using indigenous technology and design was a very bold act,” says Prof Govindarajan.

To this end, an integrated design and manufacturing centre was set up at their Kandivali plant in Mumbai. Goenka hired a number of engineers (half of them just out of college). “We did the initial styling but did not have the capability to make the clay model, or design the body. For that, we opted for a UK consultant,” he says. In fact, he adds, bulk of the development was led by consultants. For instance, AVL Austria designed the engine. However, M&M ensured that its engineers worked alongside the consultants during this process. “It cost us money to send scores of engineers abroad for many months. But we saw that more as an investment,” Goenka adds.

Other risks had to be taken as well. There was no expertise in India to build either a press or paint or body shop. Buying these from established players would prove prohibitively costly. M&M began to scout for other options. For instance, it identified a Korean company which had some expertise in body shops but had never developed one fully. However, M&M still gave it the order. Reason: It would cost half the amount it would have to pay established players. A paint shop, set up as part of the Ford-Mahindra joint venture in 1994, was put to use for Scorpio. Such jugaad was necessary to keep costs low.

Inevitably, Scorpio’s development cycle had its moments of crisis. “There was a lot of nervousness and challenges. We thought of abandoning the project mid-way many times,” says Goenka. It was Anand Mahindra’s encouragement that helped the project stay on course, he adds.

![mg_78671_mahindra_strength_280x210.jpg mg_78671_mahindra_strength_280x210.jpg]()

Five years and Rs 550 crore later, Scorpio was launched in 2002. The urban customers loved the product and sales picked up dramatically. Three things went in favour of Scorpio—its aggressive styling, powerful 109 horsepower engine and a price point of Rs 6 lakh. The company was bent on making Scorpio a success. After all, it had invested almost four times its annual profits on the vehicle, and failure was not an option. Given that, it initially even sold a variant of the vehicle at a loss of 2 percent (a first in its history) it also dropped the Mahindra name from the brand just in case the ‘rural’ image put off the urban customer.

The Scorpio’s eventual success offered several learnings to M&M. First, that it has the capacity to develop all-new vehicles. Second, to develop those vehicles, it needs to build the necessary capabilities in-house rather than rely on consultants. This would help reduce costs and lead time to the market. Third, customers would not always be charitable. Consider that Scorpio, when it was launched, was far from perfect. “Customers took pride in the fact that it was the first SUV that was developed in India. They gave us a long rope, ignored shortcomings and allowed us to correct the product over time. Had we launched Scorpio five years later, it would have been a big failure,” admits Goenka.

The need to enhance and refine the product development process became obvious. But Scorpio had drained the company’s resources and they had to hit the pause button on the plan of revamping capabilities.

Not for long though: As Scorpio’s success grew, so did M&M’s revenues and profits which rose sharply from Rs 4,626 crore and Rs 146 crore respectively in 2002-03 to Rs 11,645 crore and Rs 1,068 crore by 2006-07. And this, in turn, accorded Anand Mahindra with the opportunity to fulfil his dream.

The Dream Project

In 1991-92, while on a visit to Chrysler Motor’s research facility in Auburn Hills, Michigan, Anand Mahindra was intrigued by the architecture of the facility. “It had a unique structure where no department was more than a 10-minute walk from the cafeteria,” he says. “I was told that it was to create an environment where engineers from various departments can share notes when they eat.” That was when the automotive world was moving towards simultaneous engineering in product development. Getting engineers to communicate, even in those casual environs, had helped the auto major significantly.

This thought stayed with him. Later, on a visit to Xerox’s PARC (Palo Alto Research Centre), he was struck by the environment which, he felt, fostered creativity: The peaceful surroundings, a strong ecosystem for R&D and facilities which allowed people to live, work and play. He wanted to create similar facilities for M&M in India. “Anand Mahindra discussed setting up such a facility soon after I joined, but conditions then were not ripe, both within the company and outside. We simply focussed on getting the products out,” says Goenka.

It was only in 2005 that he began work on Phase II of M&M’s product development journey, and sowed the seed of what is now known as the Mahindra Research Valley (MRV). “MRV was conceptualised as an integrated product development centre that will have the best environment, infrastructure and people for R&D in the auto industry,” says Rajan Wadhera, chief executive, truck and power train division at M&M, and head of MRV. “It would also be seen as a temple of learning which will attract top talent in the field from around the world.” A budget of Rs 1,000 crore was allotted for it.

![mg_78673_mahindra_and_mahindra_280x210.jpg mg_78673_mahindra_and_mahindra_280x210.jpg]()

And, on April 11, 2012, former India President APJ Abdul Kalam inaugurated MRV. Spread over 124 acres inside Mahindra World City (India’s first special economic zone and an integrated business city), a 90-minute drive from Chennai, MRV has 500,000 sq ft of built-up area housing 32 laboratories to physically make parts, do mock-up testing for use and abuse of various components, and design offices to virtually validate designs and test them.

On last count, it had 2,600 engineers including 10 expatriate employees working across four major domains—auto product development, farm product development, power train engineering and advanced technologies. M&M has spent about Rs 650 crore on the facility so far, and the annual wage cost of people involved in R&D as a proportion of the company’s total wages has risen to 20 percent in 2014 (it was 8 percent in 2004) in just the auto division. “It is the only place in the world where automotive and tractor development takes place under one roof,” claims Goenka.

A Bumpy Ride

Expectedly, M&M faced many challenges in setting up the MRV. “Where should we locate it was the first issue. Should it be near a manufacturing facility or away from it?” recalls Anand Mahindra. “We opted for a place away from a plant as M&M had many manufacturing facilities and MRV cannot be close to all of them.” The other big challenge was moving around 1,000 product development staff from Nashik and Kandivali (in suburban Mumbai) to the outskirts of Chennai. “Many left and those who took the transfer found it difficult as social infrastructure around MRV was not developed. They liked the workplace but their spouses found things difficult,” says Goenka. To fix this, the company invested in schools, housing and clubs.

Recruiting new staff also presented a problem. “India has been known, for many decades, as a manufacturing country but we never designed or developed auto products. This meant that there was a serious lack of people with product development expertise,” points out Wadhera. So, M&M opted for the next best option: It recruited engineers directly from college and trained them.

The most significant challenge was fostering a mindset change among the engineers. Creating a culture of innovation, risk-taking, and an open environment that facilitated cross-pollination of ideas was critical for MRV to deliver results. But the situation at M&M was far from that. “Before relocating to MRV, the development teams that were located in Nashik and Kandivali worked in silos [locationally and functionally] and a culture of innovation was nascent,” says Rajeev Dubey, president (group HR, corporate services & aftermarket sectors), M&M.

Here’s where the Rise campaign that M&M launched in 2010-11 became relevant. The idea was to create an ecosystem that fosters a culture of accepting no limits, alternate thinking and positive change. It rewarded people who were both logical and creative at the same time, co-creators (rather than control freaks) who nurtured an environment which was devoid of fear, encouraged risk-taking and built trust. It took a while for this to manifest but reducing attrition levels indicate a promising movement. “Our attrition level has come down in the last three years, from a high of 15 percent to less than 10 percent,” says Dubey.

![mg_78665_mahindra_scorpio_280x210.jpg mg_78665_mahindra_scorpio_280x210.jpg]()

Since its launch, three new products have emerged out of MRV. The XUV 5OO was developed in four years at a cost of Rs 650 crore (25 percent lower than Scorpio at then prices). It has since become the fastest-selling SUV priced above Rs 10 lakh to sell one lakh units (it did it in little over 30 months).

Arjun Novo—a tractor developed at a cost of Rs 300 crore—will give M&M technology leadership, believes Goenka (it is already the market leader in the tractor industry). Over 2,500 units of Arjun Novo have been sold in the last two months. The third product, the New Scorpio, was launched recently with updated design and technology. “Engineers at MRV are working on 20 new products/variants and three new tractor platforms apart from developing many new technologies ranging from in-car infotainment, alternate fuels, emission and safety standards and light weighting the car to improve fuel efficiency,” says Goenka proudly.

MRV has also helped M&M improve the quality of all its products. “At any given time, over 300 tests are being conducted to improve performance and customer experience—be it door-handling, seat comfort, suspension, engine noise and so on,” says Wadhera.

Bridging the Gap

The results are visible in the market. American marketing information services firm JD Power’s Customer Satisfaction Index reveals that M&M vehicles have moved from the ninth place in 2005 to the fourth in 2014. Also, under JD Power’s Initial Quality Survey 2013, Scorpio and Xylo are among the top three vehicles in the SUV and MPV categories respectively. This survey takes into account problems per 100 vehicles as reported in the first 90 days of new vehicle ownership.

On the flipside, though, a closer look at the survey reveals a huge gap between M&M and other global players. While Toyota’s Fortuner recorded just 53 problems in the SUV category, Scorpio recorded 117.

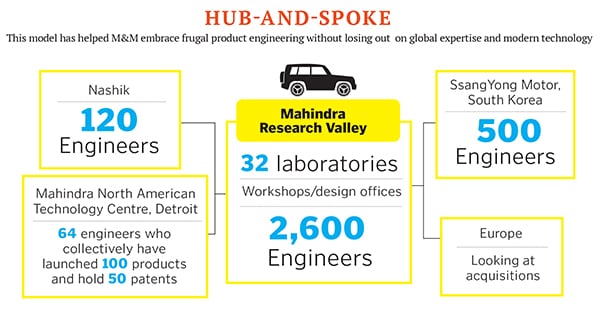

Goenka realised these limitations vis-à-vis well-entrenched global players. “India lacks a strong base for automobile technology and engineers with years of expertise,” he says. To bridge this gap, he entered phase II of his strategy by setting up a technology centre in Detroit earlier this year. The Mahindra North America Technology Centre (MNATC) with 64 employees effectively complements MRV.

While the average age at MRV is around 30, the employees at MNATC hold 1,200 years of experience between them along with 100 vehicle-launches and 50 patents. “We set up MNATC to speed up our development prowess. At times, there is a need for vertical capacity building as there is no time to [ride the] learning curve,” says Wadhera. In the next five years, the Detroit centre will be expanded to house 500 staff members, and will focus on fit and finish as well as reliability among other aspects.

These moves point to the creation of a hub-and-spoke product development model at M&M. At the core is MRV with young engineers and the necessary physical infrastructure. MNATC brings experience (the engineers in Detroit will handhold those at MRV) and technology to the table. The Nashik facility handles platform engineering which basically serves existing models.

The other crucial link in the model is SsangYong Motor’s research facility (M&M had acquired the Korean company in November 2010 for $463 million). M&M and SsangYong are already collaborating on developing four new engines. This joint effort includes both designing and sourcing. “We are also looking at facilities in Europe that will further our development capabilities,” says Goenka.

BVR Subbu, former president of Hyundai Motor India and founder of Beyond Visual Range, a strategic consultancy firm, says, “M&M has managed to create a relatively unfettered product development structure which acquires, assimilates, absorbs technology and takes it to the next stage. This will hold them in good stead.” The young workforce in product development seems to be learning very fast, he adds.

![mg_78667_mahindra_suv_280x210.jpg mg_78667_mahindra_suv_280x210.jpg]()

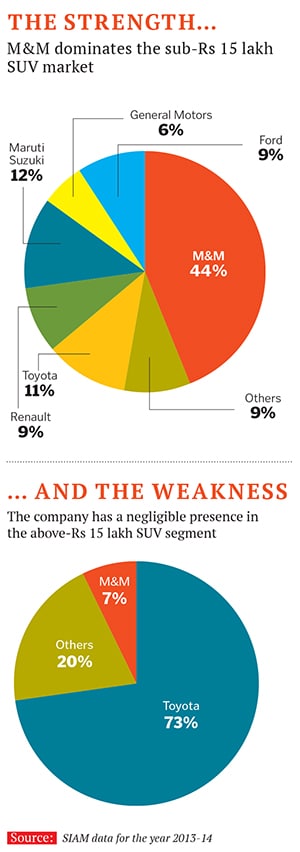

With so much already in place, the next question is: Will M&M get out of its comfort zone (which is the sub-Rs 15 lakh category in SUVs in which it has a strong 44 percent market share) and challenge global players in the premium SUV segment? “We need to develop the requisite technology and finish such vehicles require. This expertise comes from large R&D budgets, developing thousands of new models and producing millions of vehicles. We are getting there,” Wadhera says. Toyota typically invests $2 billion a year on R&D while M&M can only put in $200 million though both the companies are investing similarly in terms of percentage of sales.

But Goenka is not one to wait. He is already charting the next phase of M&M’s product development strategy which will focus more on building technology. “Most of the technology that we use in our cars is developed outside the country. We will get a real competitive edge only if we develop our own cutting edge technologies,” he says.

However, this is a high-risk exercise as it requires massive investment and the hit-rate is low. For that, he offers a solution. “The government of India should step in and create an environment where we can access public funds, use knowledge/expertise available in universities and government labs such as DRDO [Defence Research and Development Organisation] or CSIR [Council of Scientific and Industrial Research],” he says. He gives the example of South Korea where, in the 1970s, 80 percent of R&D spends was incurred by the government.

![mg_78675_mahindra_propduct_development_280x210.jpg mg_78675_mahindra_propduct_development_280x210.jpg]()

“A long-term technology vision is the key,” Goenka says, adding that it can be woven into Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ‘Make in India’ initiative which should consider not just manufacturing but also technology. “Otherwise manufacturing will lose its competitiveness in India once wage costs increase,” he cautions. Germany, he points out, developed technology and thus continues to have a strong manufacturing base despite higher wage costs.

Fortitude and Fortune

While these may seem tall tasks, Goenka has battled enough perceived drawbacks in his own life to be frazzled by even the most ostensibly impossible situations. Even from a younger age, Goenka (now 59) never allowed limitations to come in the way of his dreams.

Born in a middle class Marwari family in Madhya Pradesh, he was educated in a Hindi medium school in Kolkata. English was never his forte but that did not prevent him from pursuing mechanical engineering in IIT-Kanpur, a Masters/PhD from Cornell University and joining General Motors in Detroit. (Folklore has it that his English communication was so patchy that General Motors put him and a few others with similar limitations through a 14-week communication course in the language.)

In all this, his fortitude has propelled him in his career. His meteoric growth within the Mahindra group is a clear testimony. Goenka, who joined as GM-R&D in 1993, became COO of the automotive business in April 2003 and president of both automotive and farm equipment businesses by 2010. He was made the executive director of the company in September 2010 and a member of the board as well—the first employee to be included in over 20 years.

Have the last few years at M&M validated his return to India?

“I am very happy to be a part of this journey at M&M,” says Goenka. And his response is not faux humility, but is in sync with the reality too. Because while the team, led by Anand Mahindra and Goenka, has achieved several perceived impossibles, the fact, as Wadhera puts it, is this: “For every two steps, we take the world has already taken four steps.”

Clearly, Goenka’s journey is far from over.