How Indo Count's capital-light model helped it carve a profitable niche

With a capital-light business model, Indo Count has carved out a profitable niche for itself in the home textiles business

At Indo Count’s spinning facility in Kolhapur, Maharashtra, 80,000 spindles churn out 40 tonnes of yarn a day. Cotton is fed into the machines, fine thread is spun and after a five-step process, the yarn is produced—the first in a series of steps as the yarn winds its way through the facility before ending up as bed sheets and pillow covers sold in the United States on the shelves of retailers such as Wal-Mart and Bed Bath & Beyond.

While the majority—65 percent—of Indo Count Industries Limited’s business comes from retailers in the US, it also exports to 54 countries and has taken baby steps in selling products under its own brand, a bold step for a company that was set up only in 1991 as a yarn maker and entered the home textile business in 2006. In August, it also plans to launch its range of bed sheets in India under the Boutique Living brand.

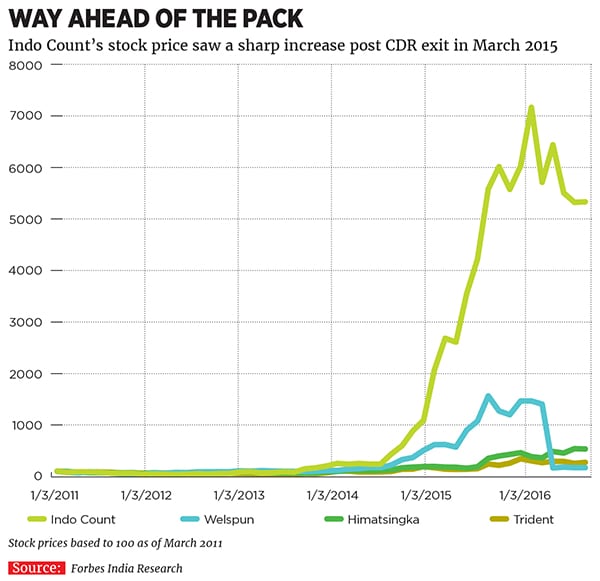

In the last decade, a handful of Indian home textile companies—Welspun, Alok Industries, Himatsingka Seide, Trident Industries and Indo Count—have carved out an enviable 47 percent share of the bed linen segment in the US market. Simply put, there is, today, an equal chance of bedding sets sold in the US being made in India or China, which earlier had a much larger market share. In India’s case, it took a smart set of entrepreneurs to tap this opportunity after the abolition of World Trade Organization textile quotas in 2005. What this meant was that countries could no longer discriminate about where the goods came from. As margins in the home textile business are far better, some companies decided to try their hand at this. But this is also a business that takes time to break into since retailers tend to be very finicky about whom they contract to. But once the contracts are in, they are inclined to be long-term and sticky.

It is in this highly competitive and specialised business that Indo Count, run by Anil Kumar Jain, 63, and his son Mohit Jain, 40, has carved a niche for itself. As Mohit admits, “We looked at a whole host of other businesses, from flexible packaging to co-generation of power from sugar mills and hydropower, in the early 2000s.”

The shift is remarkable, given that most of India’s textile companies are still in the spinning business and haven’t managed to make the transition to value-added products. Spinning is capital-intensive, where capacity needs to be added at regular intervals. And single-digit margins mean that companies can never earn enough to add this capacity without taking on debt. As a result, profitability is always low. But Indo Count has chosen to build itself differently. “This is an industry that is characterised by high capital expenditure, low return on capital employed and low asset turnover. Indo Count has chosen to outsource and so its use of capital is far more efficient,” says Sandeep Raina, vice president at Edelweiss Global Wealth Management Research. In the last five years, revenues have risen 25.5 percent annually to Rs 2,070 crore while profits have touched Rs 250 crore in the year ended March 31, 2016.

Of Beginnings

In 1990, before they started Indo Count, Anil Kumar Jain, chairman, was far removed from the textile business. “In 1975, my father had bought me a brewery and I ran it along with my cousin,” he says. During those days, his brother-in-law, based in Manchester, England, would often complain about the quality of yarn available in India. He convinced them there was an opportunity in the business, and that sowed the initial kernel in Jain’s mind.

With the economy opening up, the government had also announced a host of incentives, including an exemption from import duties for factories set up as ‘export-oriented units’. Jain decided to get into the business and placed an order for machines from Reiter, a Swiss manufacturer. “There hadn’t been any orders from the Indian market for the last 30 years, so Reiter was reluctant to come back, but the demand was so high that when their representative landed in India, he had to also give appointments on the way from the airport to his hotel,” says Mohit Jain, managing director at Indo Count.

Anil went off to Kolhapur in south Maharashtra and bought land in a region known for its cotton. The company began operations in 1991 with a capacity of 12,000 spindles and with all the yarn being exported. Capacity was swiftly expanded to 60,000 spindles in the next five years and Indo Count clocked revenues of Rs 150 crore. Over the next 10 years, till 2005, the company continued to serve its clients. “By 2005 the company was debt-free, it had a regular dividend payout and had created an export-oriented culture where serving clients and supplying a high-quality product was paramount,” says KK Lalpuria, executive director at Indo Count. They then decided to leverage their balance sheet and make use of the government’s Technology Upgradation Fund to buy machinery.

It was at this juncture that the company confronted a fork in its path. In order to move into the business of manufacturing finished products (which has higher margins) Indo Count decided to outsource some part of its low-margin business of simply spinning and selling yarn, a move that most other spinning companies don’t make. At present, the company produces 30 to 40 percent of the yarn it consumes the rest is outsourced. “We could have either continued to invest in the spinning business or moved up the value chain,” says Mohit, who, as a 29-year-old, led Indo Count’s charge into the home textile business. The phasing out of textile quotas meant companies like Dan River and Springs Global, which would earlier manufacture in the US, could now pay low import tariffs and import instead. At that point, India had a 10 percent share of the US bed linen market.

Homing In

Getting into the US home textile market takes a while. This is something Mohit would quickly learn. First, he engaged Swiss consultants Gherzi to help the company chart its entry into the market. Next, he started meeting buyers with a blueprint of their plans. He’d explain they had been in the yarn business for 15 years and were looking to enter the home textile business. Now, retailers are very careful about signing on new suppliers and getting their quality specifications right tests a lot of suppliers. On-time delivery is key and a missed shipment can permanently impair the relationship. Still, Indo Count managed to sign on Springs Global and Belk, a retailer based in Charlotte, North Carolina. There was no looking back then, though it would be three years before Indo Count’s manufacturing capacity of 36 million metres would be fully utilised.

That was in 2012. At the Kolhapur facility, the company has set up a state-of-the-art plant where yarn is processed. The cloth is then dyed and printed, and the bed sheets and pillow covers are ‘cut and sewn’ before being packed into boxes. Indo Count has now expanded capacity, in three phases, almost three-fold from 36 million metres to 90 million metres by December 2016.

As an exporter, Indo Count has had to deal with three types of key risks over the years. First is a sudden fall in demand due to a recession in the developed world. “Could demand fall tomorrow? The answer is yes,” says Mohit, but he explains they have access to live data on what is selling at the retailers they supply to and so orders are tweaked accordingly.

Second, Indo Count’s earnings are vulnerable to currency fluctuations. The company had an unfortunate experience in June 2008, when their erstwhile CFO signed a zero-cost derivative contract. This was a time when the rupee was quoting at 40 to the dollar and consensus was that it was expected to strengthen further. In order to lock in their dollar receivables, the company got into a contract that stipulated they would have to pay double the amount if the rupee depreciated. That is exactly what happened and Indo Count was saddled with a Rs 150 crore loss. “We just didn’t know what to do,” says Anil. They could have sued the banks that sold them the contracts as they were sold without being signed by two signatories. Instead, the company decided to repay what they owed. The decision resulted in Indo Count going for corporate debt restructuring, which set them back by at least three years. Although their customers were still serviced on time, payments to suppliers were delayed.

Indo Count has now put systems and processes in place to ensure a repeat never occurs. They would typically hedge about 60 to 70 percent of their dollar receivables over the next one year and stick to pre-decided limits. “What I like about them is they don’t change their strategy based on short-term currency fluctuations,” says Abhishek Goenka, managing director at IFA Global, which advises them on their foreign exchange and treasury strategy. Indo Count’s credit rating has also allowed them to avail cheaper dollar borrowings, bringing down their overall cost of working capital.

Third is the risk of cotton prices fluctuation, cotton being a key raw material. In the last month, a sharp and sudden rise in cotton prices has been an overhang on the sector. This was the result of low supply due to a poor monsoon in 2015. This led to the Cotton Advisory Board pegging the closing stock figure at 17 million bales in June. This has recently been revised to 43 million bales, which should lead to a tempering of prices.

Indo Count says it has enough cotton to keep making yarn till November when a new crop should stabilise prices. The global cotton price index (the Cotton Season Index A) has risen 17 percent between April and July 2016 to 81 cents per pound. Indo Count has also decided to import cheaper cotton from Australia. However, they do concede that, going forward, rising prices could cause a dent in their Ebitda margins, which, at 21.5 percent, are the highest in the industry.

The Road Ahead

After having established Indo Count as a leading supplier of bed linen, the Jains once again had to brainstorm on the next steps, while leveraging on its existing strengths.

The fashion bedding space, which comprises duvets, comforters, quilts as well as mattress protectors, was an obvious extension. Indo Count is also looking at institutional sales to hotels, a space that has so far been served mainly by Chinese companies. It has also set up B2B showrooms for retailers in New York, Manchester and Melbourne.

For those who don’t want to order in large quantities and want to avoid the shipment or freight risk, the company has set up a warehouse in Charlotte to ship out bed sheets in smaller numbers. Indo Count’s bed sheets are also available on Amazon under their house brand.

Later this year, the company plans to stock its own brand at retail outlets in the US. Typically, 75 percent of the stock at a department store is the retailer’s brand. Branded products by manufacturers (which Indo Count is targeting) make up the balance 25 percent, but yield higher margins. This is also a sign of the confidence of a manufacturer that its product will sell, since the risk of no-sale is with Indo Count.

For the Indian market, Indo Count has tied up with Asim Dalal, who set up The Bombay Store, to market a range of bed sheets as a premium product—priced between Rs 2,000 and Rs 9,000—through Indo Count Retail Ventures, in which Dalal holds a 20 percent stake. In the next five years, the company targets Rs 500 crore in revenues from the Boutique Living brand.

As is evident, the business is about staying ahead of the game: For instance, the company recently came out with a patented fabric that absorbs body heat when it is hot and radiates it when it is cool.

Innovations like these help Indo Count stay one step ahead of competition. And while some factors, like cotton prices, are beyond its control, it says it’ll do everything to ensure that nothing like the forex derivative loss happens again, even as they become more and more integrated into the global supply chain of their retail partners.

First Published: Aug 30, 2016, 06:41

Subscribe Now