How Edelweiss built a business for the long run

Though Edelweiss has failed to get a banking licence, it has built sufficient headroom to grow in multiple businesses. For now, that should be enough

At the 15th floor boardroom of Edelweiss House in Mumbai’s Bandra-Kurla Complex financial hub, Rashesh Shah, chairman and group CEO of Edelweiss Financial Services Ltd (EFSL), walks us to the large glass windows and asks us to glance at the sprawling, open MMRDA grounds below. “We get a great view of open spaces,” says the 51-year-old co-founder of the diversified financial services group. “Closer to the edge, the view might be better. But we don’t need that. I can stay three steps away and the view is still as good. I don’t need to go to the edge,” he points out.

As it is with views from windows, so it is with business. This philosophy—which Shah calls the ‘margin of safety’—has not only saved Edelweiss the blushes (of possible financial losses) but has, in fact, become its mantra for success.

Shah explains this with the example of wholly-owned subsidiary Edelweiss Commodity Services Ltd, set up in 2006 as part of their strategy to diversify from being a capital market-led firm nearly two decades ago. The commodity subsidiary sources, distributes and helps in the financing of agri-commodities and precious metals, earning it a 14 percent annual return. In a country where commodities change hands frequently, evaluating them and managing risk are critical.

In 2013, some of India’s large brokerage firms suffered losses in the fallout of the Rs 5,690-crore financial imbroglio at the Jignesh Shah-promoted National Spot Exchange Limited (NSEL). Contracts were sold to investors without necessary collaterals in place, resulting in defaults and losses.

It is in this context that Edelweiss’s risk philosophy—of staying away from the edge, despite the better view—worked for the company.

Edelweiss’s risk management team had considered the attractive brokerage fees that could have potentially come their way. “In fact, there was one client who was upset that we did not provide him with the opportunities to make good returns,” an Edelweiss insider said, requesting anonymity. But Edelweiss chose to stay away. “We stayed out of broking at NSEL because we understood that on the warehouse side, risk management is the most critical. We prefer a situation where we manage the collateral and then fund it,” Shah says, rather than the reverse.

Prudence proved to be the better part of valour

Today, Edelweiss is among the few financial firms of its type: Set up by a couple of entrepreneurs in late 1995 with its roots in the capital markets, it has, two decades later, branched out into a well-diversified financial services group. In the process, it has not followed the same path as that of experienced, niche players, such as Shriram Transport and Muthoot Finance, which operate largely as commercial vehicle financiers and provide loans against gold respectively. Edelweiss, as its name suggests—with no founder or family name attached to it—is one of those rare financial companies that are completely independent of the backing of large conglomerate groups like Tata, Birla, Bajaj, Reliance or Kotak.

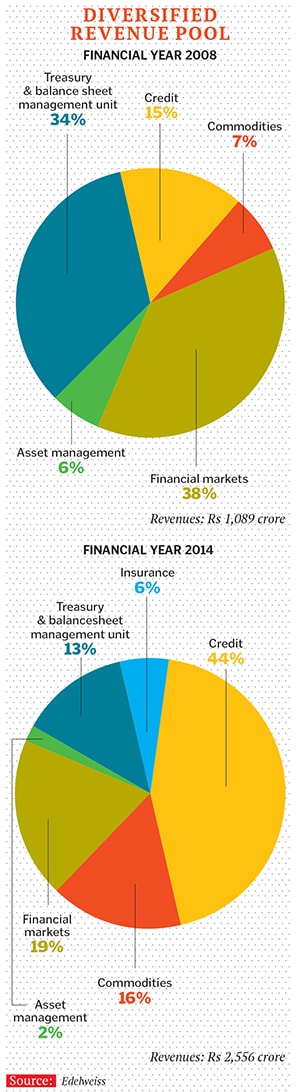

It is primarily strategic decision-making, and in some cases luck, that has brought Edelweiss to where it is today—and it is a happy place to be in. In FY2014, Edelweiss Financial Services Ltd, the parent listed company, posted consolidated revenues of Rs 2,556 crore and a profit after tax of Rs 220 crore. (In FY2007, revenues were at Rs 372 crore and profit at Rs 110 crore). In the last three years, Edelweiss has been growing at a CAGR of over 35 percent.

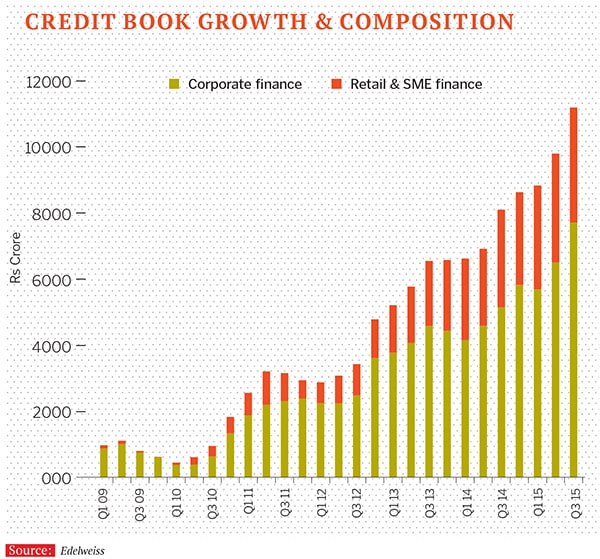

The Edelweiss group, in which Shah has a 28 percent stake and co-founder Venkat Ramaswamy 10 percent, now has five businesses— capital markets, asset management, credit, commodities and insurance. But Shah prefers to look at the company as one which is, mostly, credit-led. “In credit, we are at about Rs 12,500 crore of total assets [of the total Rs 23,000 crore],” says Shah. Credit thus forms about 55 percent of the balance sheet, as of December 2014. The agency-led business is in the range of Rs 3,000-4,000 crore. Another Rs 4,000-5,000 crore is in the form of liquidity and treasury management while Rs 2,000-3,000 crore include its corporate assets, investments in its insurance joint venture with Japan’s Tokio Marine Holdings and the Edelweiss office building. By 2020, Shah is confident that Edelweiss will be an 80 percent credit-led group, with the balance in non-credit businesses.

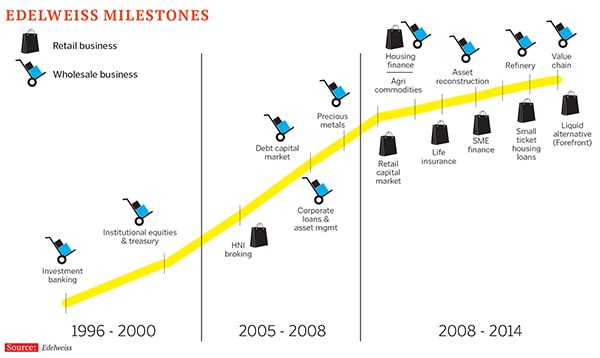

The bulk of Edelweiss’s evolution from a full-fledged capital market firm to a financial services powerhouse has taken place in the past seven years. Much of it was built on a growth strategy of diversifying into adjacent markets and newer asset classes. Investment banking led to institutional broking, later expanding into NBFC activity, followed by a whole range of credit-related businesses between 2008 and 2012.

Edelweiss has also had its share of disappointments. Once diversified, Edelweiss applied for a licence to set up a bank when the Reserve Bank of India, in 2013, announced guidelines for the setting up of new banks. But though they were unsuccessful, there was no despair. “Hopefully, it [the licence] should come in the next five years. Right now we are small but we have enough runway [for growth] in all our new businesses of insurance, asset management, distressed and structured credit,” Shah says. “Our aim is to grow the credit business by 30 percent a year, till 2019-20.” (On an average, a large NBFC has Rs 40,000 crore and a small bank Rs 50,000 crore in assets. Kotak Mahindra Bank was the first case in India’s banking system which made a natural transition from being an NBFC to becoming a bank.)

“In the next four to five years, we should become a bank. We don’t want to become a bank at any cost—like a payment bank or small bank. That is not us,” Shah adds. “We are hungry but we are not bhookad [ravenous].”Investors back Shah’s line of thinking. “If Edelweiss had stayed in the capital market segment, profits would have fallen due to a smaller profit pool,” says Akash Prakash, CEO of Singapore-based Amansa Capital, which has a 1.5 percent stake in Edelweiss. It should be noted that Edelweiss was always an institutional brokerage that bulked up its retail business when it took over Anagram, which had more than 1.8 lakh clients, in 2010, and estimated revenues of Rs 100 crore.

“Firms like Edelweiss, IIFL Holdings and Motilal Oswal Financial Services morphed themselves into full-fledged financial services firms out of the urgent need to grow. But very few companies in the capital market space have managed to scale up business,” says a research head at a Mumbai-based financial services firm, requesting anonymity. Prakash, like other experts, agrees that Edelweiss’s natural transition would be to become a bank: “That is the long-term trend in India’s financial system.” In the case of Edelweiss, this move is particularly inevitable since it isn’t in a niche business like Cholamandalam Finance or micro-finance firms, for example.

The founders of Edelweiss could have scarcely imagined this outcome when they set up the business.

Edelweiss had a modest start. Shah, who as a student was interested in statistics, preferred not to join his family’s stationery business and opted for the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad. In 1989, Shah started working with ICICI (it was not a bank then) and gained the experience of working with export-oriented companies. This is where he met Ramaswamy.

Shah left ICICI in 1993 to join Prime Securities as head of research and investments. Ramaswamy, with an MBA from University of Pittsburgh, had also left ICICI to join Spartek Emerging Opportunities fund—India’s first foreign private equity fund, based in Chennai—as a fund manager. For both Shah and Ramaswamy these moves were vital stepping stones to honing their entrepreneurial abilities these opportunities had come to them at a time when India’s capital markets had opened up to foreign investments, companies were going public and private placements in listed companies were the buzz.

“I got a call from Rashesh, who said it was a good time to start our own business,” recounts Ramaswamy, 48. Edelweiss Capital, as it was then called, was originally formed to have a team of five, including some Prime Securities staffers. They never joined.

But Shah wasn’t worried—he had big plans anyway. This was to be a boutique investment bank with a category I merchant banking licence and based in south Mumbai’s famed business district of Nariman Point. To be a category I merchant banker, they needed to raise Rs 1 crore. Shah convinced his father to mortgage their house at Mahalaxmi in Mumbai, while Ramaswamy sold the Infosys shares which the IT giant’s founder NR Narayana Murthy had offered him (they knew each other during the ICICI days) before the company went public in 1993.

Shah and Ramaswamy managed to raise the required capital for the company, but, just then, the regulator Securities and Exchange Board of India hiked the category I merchant banking requirement to Rs 5 crore. “This forced us to look at other avenues for growth and not work on initial public offerings [IPOs],” Shah recalls. It was a blessing in disguise. Edelweiss focussed on portfolio management and helping first generation entrepreneurs raise capital through private equity transactions.

“All our initial clients were cold-called,” Ramaswamy reminisces about the early years of struggle. Edelweiss’s first deal was to try and raise capital of about Rs 30 crore for the south Indian firm, Madras Suspensions. “But PE investors did not put in money and we were unsuccessful,” Ramaswamy says. “My gut feel is that if we had closed the Madras Suspensions deal, Edelweiss would have been a different type of company.”One of Edelweiss’s first M&A deals was to help the sale of Thiruvananthapuram-based Peninsula Polymers to Japan’s Terumo Corporation in 1999. This set the ball rolling and Edelweiss in the next two years helped companies like Rediff, India Infoline (later called IIFL Holdings), Daksh and Educomp raise capital successfully. In the first five years of operations, Shah and Ramaswamy took Rs 25,000 per month as salary to keep costs low. Shah fondly calls his capital market division the “intellectual hub” of Edelweiss, as long-standing business relationships were built there. Till 2008-09, the capital market business comprised 60 percent of EFSL’s business. Today, it is down to 20 percent, though volumes have grown.

But in the initial three years, the co-founders realised that while investment banking and the institutional brokerage business would grow, it would be volatile and directly dependent on financial market trends. “Further, there was no scale. The profit pool in capital markets is about 1/20th that of the pool in the credit business,” Shah says. Edelweiss was then competing for business with established firms like Enam Financial and JM Financial. That was when it decided to move to spaces that offered larger opportunity or where the sector was growing at a brisk pace, Shah says.

By 1998, Edelweiss had hired its third employee, Shriram Iyer, for investment banking. (He later occupied several top positions in EFSL and left only a few months ago.)

Clearly, the late ’90s saw the worm crawl upwards for the company. Madrid-based non-resident Indian Harish Fabiani, who was to later fund firms like Nimbus Communications and Indiabulls, became an angel investor in Edelweiss in 1999, putting in Rs 1 crore. The next year, Edelweiss got its first round of formal funding from Connect Capital Holdings, which invested $2 million for a 10 percent stake. This additional capital helped Edelweiss buy out brokerage firm Rooshnil Securities in 2002, which later became Edelweiss Securities Ltd, the group’s broking arm.

By then the plan was to expand beyond investment banking and institutional brokerage into derivatives trading, and Edelweiss set up a research and analytics desk. And the right people also followed. Himanshu Kaji, now Edelweiss group’s chief operating officer, was an early technology consultant for Edelweiss. Kaji had been instrumental in the overhaul of the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) as it became corporatised. Later Deepak Mittal, who now heads the life insurance business, joined to head the analytics division. This was followed by Nitin Jain, who runs the retail capital markets and wealth management divisions.

The pattern is self-evident. In each of its ‘difficult’ phases, Edelweiss has identified areas of growth, moving from an investment banking firm to a broad-based capital markets company by 2003. In the slowdown of 2001-03, it focussed on corporate finance, retail stock broking and the IPO business. By 2005-06, it was a full-fledged capital markets firm. The thought of shifting towards credit came when London-based Greater Pacific Capital invested Rs 80 crore into Edelweiss, by buying out Connect Capital’s existing stake and pumping in additional capital.

“To be in credit, we needed a net worth of at least Rs 100 crore,” Shah says. Edelweiss’s net worth was just Rs 54 crore in FY2005. (It has since risen to Rs 3,095 crore in FY2014.)

In 2006, Edelweiss formed its NBFC, ECL Finance, which like its peers has been playing a stronger role in recent years, even while banks remain the dominant force for credit. Keeping its ‘adjacent markets’ strategy in mind, ECL started with corporate lending and advisory and capital-market oriented credit business like margin funding, IPO financing and loans against shares/ESOPs.

Lehman came to India at around this time and picked up a 26 percent stake in ECL Finance. This was the period when several global investment banks—Citigroup, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs—were scaling up their presence in India, as banking services fuelled local economic growth. Edelweiss Financial Services has since bought out Lehman’s stake in ECL Finance (after the bank’s collapse in 2008). EFSL holds a 92 percent stake in the subsidiary and Singapore’s GIC has the balance.

One of the strategies which Edelweiss was fortunate with—finding the right people for the right job—worked for them in their next phase of expansion. Siby Anthony, a director with Asset Reconstruction Company (Arcil) India, decided to join Edelweiss in the group’s asset reconstruction company (ARC). The ARC is part of the asset management business, along with private equity and mutual funds. Edelweiss’s asset management division has over $3.5 billion worth of assets under management.

“When we started, no bank was selling assets to ARCs. We thought we should get into distressed credit: Buying out distressed assets at deep discounts and trying to revive them,” says Anthony, CEO of Edelweiss ARC in which EFSL holds a 49.9 percent stake. Edelweiss ARC started with Rs 45 crore seed capital from Edelweiss and invested in three assets: A denim textile manufacturing unit in Ahmedabad, a poultry unit in Hyderabad and a milk processing unit in Punjab. It exited all these investments by September 2014.

The ARC team has grown to 40 in 2014 from just three in 2008. By December 2014, it had a total of Rs 18,500 crore as assets under management, with cash invested by Edelweiss ARC being Rs 1,400 crore in over 450 companies. Arcil, India’s oldest ARC, has AUM estimated at Rs 10,000 crore.

And that tells a story, a story that has won Shah plenty of appreciation, even from among his competitors. The chief executive of a leading financial services firm backed by a large conglomerate, says, on condition of anonymity: “Rashesh’s model is similar to that of Goldman Sachs. He has built businesses flanking his core business of capital markets. I am a great admirer of his strategy.”

He isn’t flattering either.

In 20 years, Shah and his team of nearly 6,000 employees have built a quasi-banking empire. He has ensured that when the RBI opens up the sector on tap and if Edelweiss gets the banking licence, it would—at the least—be running on a flat surface. Shah is confident that India is on the path to becoming a $5-trillion economy by 2025. With about 18 to 20 large financial institutions and banks, the opportunities are plenty. But this marathoner admits that the road ahead is “challenging”, particularly as it seeks to gain market share in new businesses.

Risk control will be a critical factor, particularly in the commodity financing space. Shah believes Edelweiss could see five painful years in its commodity business, despite the opportunities. Commodity assets in warehouses are estimated at Rs 4 lakh crore, but formal financing from banks is about Rs 40,000 crore. It would take at least five years for Rs 1 lakh crore to come into the system. Edelweiss wants to get a 10 percent share of this amount.

There’s enough work to be done, he says, as each of his businesses allows him space to grow. Tight risk management and an eye on costs associated with running each of the businesses are the two pillars on which Edelweiss stands. At every stage, Shah and his top team weigh the risks in a transaction and the costs if they went ahead with it. If the answers work for Edelweiss, they go ahead with the move.

Not surprising then, that Edelweiss has as many as 150 people working on risk alone, and another 50 people across compliance, governance and legal. This culture of risk management and compliance will continue to guide whatever the group does, Shah asserts. If the risks and costs are weighed against it, Edelweiss will not mind giving up a deal or a business move.

“It requires supreme confidence to know that I will run slowly and still do well,” he says, admitting that he is still trying to perfect the art of not starting off too quickly while running the marathon. “In the last three years I have been applying this to my business.”

There’s something to the tortoise and hare tale, after all.

First Published: Apr 01, 2015, 07:07

Subscribe Now