Foremost among its concerns was sliding smartphone sales at home, in China, which is also the largest market for these devices, accounting for one out of three smartphones shipped worldwide Lenovo’s smartphone sales in China declined by as much as 85 percent in FY16 it had conceded substantial share to rivals like Oppo and Huawei, and was ousted from the list of the top five smartphone vendors in the world.

But where there are clouds, there is also a silver lining.

For Lenovo, that silver lining is India.

The company’s stellar performance in the world’s third largest smartphone market, which is expected to overtake the US as the second largest by 2017, has given Lenovo the conviction that it can rely on India to significantly offset the decline in its home market, thereby improving overall sales and profitability.

Lenovo’s achievements in India are the result of a unique operational strategy, implemented by the company’s local management. The key tenets of this strategy are: Taking a dual-brand approach, which has seen the company focus equally on growing both the Lenovo and Motorola brands (Lenovo acquired Motorola from Google in 2014 for $2.91 billion) a heavy initial focus on online sales channels and early adoption of 4G-enabled devices in its product portfolio.

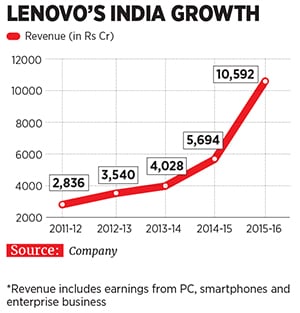

Before getting into the details of this strategy, it is worthwhile to consider how it has paid off for Lenovo. According to market intelligence firm IDC, in the April-June 2016 quarter, Lenovo (along with Motorola) emerged as the third-largest smartphone vendor in the country with a 7.7 percent share of the market by volumes, implying a shipment of 2.11 million units into the country. Only Samsung (Korean, with a 25.1 percent share) and Micromax (Indian, with a 12.9 percent share) sold more smartphones. Lenovo’s shipments in the second quarter of FY17 saw a growth of 10.3 percent over the preceding quarter, in which it ranked fourth.

![mg_89615_lenovo_280x210.jpg mg_89615_lenovo_280x210.jpg]()

In value terms, its performance looks even better: With a 9.1 percent market share, Lenovo is the second-largest vendor, after Samsung’s 29.8 percent. Samsung has been facing its own share of challenges with the Galaxy Note 7 fiasco (see page 26).

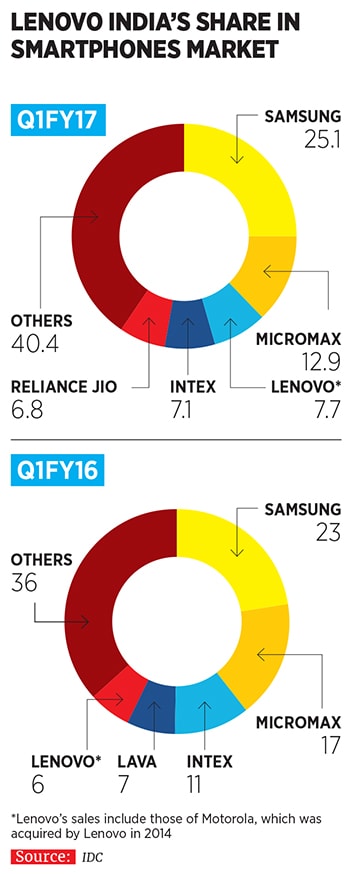

The tech giant’s Indian arm, Lenovo India, has impressive financials to boot. In FY16, the company reported a turnover of Rs 10,592 crore, nearly double the revenue of Rs 5,695 crore reported in FY15. According to data from the Registrar of Companies, in FY15, the Indian subsidiary swung into the black reporting a net profit of Rs 26.7 crore, compared to a loss of Rs 44.6 crore in FY14.

“Lenovo has obviously done much better in India than in China,” says Kiranjeet Kaur, research manager at IDC’s Asia-Pacific Client Devices Group. “It has sustained growth in the Indian market over the last couple of years with its two brands—Lenovo and Motorola—and leveraged online channels to quickly grow sales.”

If announcements made by Lenovo’s global management are any indication, then it will only step on the gas further to expand its operations in India. In a newspaper interview in November 2015, Yang Yuanqing, Lenovo’s chairman and CEO, stated that he would like to see the Indian business triple its turnover to $6 billion by FY19. And the growth in Lenovo India’s topline certainly supports this ambition.

Online First

Lenovo, which mostly sells devices priced between $100 and $250, has been a fairly recent entrant into the Indian smartphone market. It launched its first set of smartphones in India in November 2012 and has focussed on growing the business only in the last three years or so.

At the time it entered the Indian market, Samsung had just dethroned Nokia to become the top smartphone vendor in the country. Players like Micromax, Karbonn, Nokia and Sony were the other significant players in the market.

The challenge before Lenovo was to quickly grow sales and reach as many consumers as possible, without stretching costs in a hyper-competitive market that operates on wafer-thin margins. “Building a solid offline distribution network in a complex geography like India takes a lot of time and is a very costly affair,” says Tarun Pathak, senior analyst with Counterpoint Technology Market Research. “It also demands a diverse portfolio of products on the shelf, across the price spectrum, to offer a better range to the end consumer.”

This triggered the idea of adopting an online-first strategy, in which Lenovo leveraged popular online sales channels such as Flipkart to sell its products. Lenovo figured that it would lose valuable time in trying to build robust offline sales channels. “Because we didn’t have a presence offline, there was no conflict [with selling phones cheaper online than in stores]. Also, social media was used very well to create a buzz around flash sales,” says Rahul Agarwal, the 43-year-old managing director and CEO of Lenovo India, who took on this role in 2015.

As a Lenovo and marketing veteran, Agarwal is well-placed to navigate these waters: An IIM-Ahmedabad alumnus, Agarwal became a part of Lenovo when the latter acquired IBM’s PC business in 2005 (he had been employed at IBM). He has led Lenovo’s marketing communication and advertising vertical globally, sitting out of Bengaluru, before being appointed chief marketing officer for the company when it entered India. Then, he was tasked with establishing the brand from scratch, as well as launching Lenovo’s consumer business. “The journey for us becomes much more challenging and interesting now. We have grown quite a bit in India, but now the battle becomes tougher since we have to steal market share from others,” he says.![mg_89611_sudhin_mathur_280x210.jpg mg_89611_sudhin_mathur_280x210.jpg]()

Sudhin Mathur, executive director of the Mobile Business Group at Lenovo India, believes his company pioneered selling mobile phones online in India. Online sales account for a third of all smartphones sold in the country. Lenovo was the leading vendor online, with a 21.6 percent market share (by value) of all smartphones sold online in the April-June 2016 period, according to IDC. “Our target audience includes slightly younger, tech-savvy smartphone users, and they spend a lot of time online, so we thought that the best place to market and sell our phones is there,” says Mathur, who has earlier worked with mobile phone brands like LG and Sony Ericsson.

When Lenovo re-launched Motorola in the Indian market in 2014, the approach, again, was to build the brand rapidly by selling devices online first. Moto X Force was the first Motorola model that was taken offline by Lenovo now, Motorola products, especially the slightly premium ones, will increasingly find their way to retail shelves across the country, says Mathur. It is essential to provide customers with the ability to physically touch products that are at the upper end of the price spectrum, he points out.

The online-first approach reflects in Lenovo’s marketing strategy as well. Most of its promotional campaigns are online—through ads on popular websites, ecommerce and social media platforms—and not as much through traditional print or TV commercials. Apart from helping it reach its targeted audience, this has also helped the company keep costs in check and leverage the trend of sharing and liking brand messages—the online version of word-of-mouth advertising.

“What has worked wonders for a brand like Lenovo is the unprecedented ‘first day’ reach that a platform like Flipkart offers, which enables any customer from any part of the country to buy from the entire selection of phones,” a Flipkart spokesperson says. “Lenovo-Moto phones have been delivered in more than 3,000 cities and towns across India, overcoming the barrier of width of distribution that, most times, prevents customers, especially from tier 3 and 4 towns, from getting their hands on the latest smartphones.”

Having reached a certain size in the Indian market, Lenovo has now decided to develop its offline presence as well, since the remaining two-thirds of the potential market are equally important. At present, Lenovo reaches around 10,000 outlets in the country across formats including branded stores (around 1,000), multi-brand stores, and small mom-and-pop outlets. It also has a field force of 2,000 marketing executives stationed across these retail outlets. Both the store footprint and field force will grow, says Mathur, with a focus on markets that witness a lot of demand for smartphones, but not necessarily through online routes.

Another reason for Lenovo’s eagerness to expand its physical retail presence is the fact that some of its Chinese rivals, like Oppo and Vivo, have entered India as well, and are rapidly penetrating the offline sales channels by offering attractive incentives to retailers. This also reflects in their growing sales, and that’s a story Lenovo has seen play out before. ![mg_89617_lenovo_india_280x210.jpg mg_89617_lenovo_india_280x210.jpg]() Lenorola

Lenorola

One of the major contributors to Lenovo’s successes in India has been a strategy that Pathak of Counterpoint calls “Lenorola”, referring to the company’s ability to carve out market space for two strong and independent brands, Lenovo and Motorola.

This helps Lenovo attack the market at both ends of the price spectrum: Lenovo at the bottom and middle, and at a lower price point than competition and Motorola at the higher end with products for Android lovers.

India is the only country in which Lenovo and Motorola exist as two standalone brands with the parent company providing equal impetus to both. In markets like Europe, the US and Latin America, Motorola is distinctly visible while Lenovo is more prominent in countries like China and Indonesia.

According to Agarwal, Motorola accounts for a third of the smartphones that his company sells in India, with Lenovo making up for the rest. “Lenovo is a brand for the technology and internet-oriented youth who wants to experiment with a new phone with the latest specs at a good price point,” says Mathur. “While with Moto we target the upper tier of young millennials who are probably looking for a more aspirational brand.”![mg_89613_aymar_de_lencquesaing_280x210.jpg mg_89613_aymar_de_lencquesaing_280x210.jpg]()

Image: Amit verma4G Focus

But being aspirational isn’t enough by itself. Today’s consumers are particular about having the latest features on their smartphones and understanding their endurance in an environment where technology becomes obsolete in a matter of months. “You will be surprised at how discerning the young generation is!” Agarwal exclaims.

To ensure currency, Lenovo caught the 4G bug early. In the December 2015 quarter, the shipment of 4G-enabled handsets exceeded that of 3G-enabled ones for the first time in the country. Lenovo is cognisant of this. Which is why almost every phone in its portfolio is 4G-enabled, and they started selling these much before the telecom operators of the country began to promote 4G telephony services. Remember that this is a market where the reach of even 3G had been limited for a long time. Lenovo is the second-largest vendor of 4G-enabled smartphones in India after Samsung, Mathur claims. Samsung’s Note 7 woes are, however, unlikely to benefit Lenovo as it does have a product in that price segment.

The entry of Reliance Jio into the wireless telecom services space with its 4G offering will be a game-changer for the handsets industry, Agarwal reckons. (Reliance Jio is part of Reliance Industries, which also owns Network 18, the publishers of Forbes India.) Reliance Jio has offered free voice calls and data services at rock-bottom prices to India.

This has spurred incumbents like Vodafone and Bharti Airtel to offer competitively priced 4G services to subscribers and the turf war spells good news for the smartphones business. “With Jio offering data at $3-4 a month and free voice calls, we believe it can lead to a much faster growth in the smartphones market than the current projection,” Agarwal says.

The PC Challenge

Lenovo’s smartphone sales have been bolstered by the fact that these devices were introduced in India at a time when the Chinese brand was already established here. It had made big strides since it first entered the country in 2005 soon after acquiring IBM’s PC business. In fact, the exclusive stores that Lenovo has in India were set up to sell PCs and tablets, and it is only recently that smartphones have been added to their shelves.

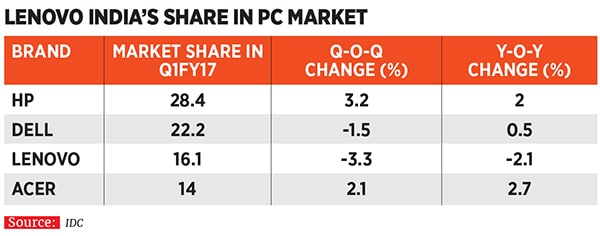

But the PC business itself is fraught with challenges, with shipments steadily declining over the last couple of years. Though, according to IDC, there has been a recent upswing in the market with shipments growing 7.2 percent sequentially in the June 2016 quarter, Lenovo’s market share during that period slipped 2.1 percent year-on-year to 16.1 percent. It ranked third after HP and Dell.

“Lenovo, like other PC vendors, has been struggling this year, primarily due to ongoing weakness in demand and declining volumes in the commercial space,” says Maciek Gorniki, a research manager at IDC Asia Pacific Client Devices Research. “Lenovo is also going through a period of restructuring, and changes in the go-to-market strategy, which is temporarily impacting its performance. Nevertheless, the vendor does and will continue to target new areas of the PC market, with ambitious plans to expand into new verticals in the commercial and consumer spaces.”

![mg_89619_lenovo_growth_280x210.jpg mg_89619_lenovo_growth_280x210.jpg]()

Agarwal contends that Lenovo’s performance in the PC segment isn’t bad if the detachable devices (laptops-cum-tablets with a detachable keyboard) it sells are also taken into account. Lenovo also ranks third among vendors selling tablets in the country, with an 11.2 percent share of that market. “Our goal is to increase our market share in the PC segment to 30-32 percent,” says Agarwal. “We are hoping that the market has bottomed out and government initiatives like Digital India will spur institutional and retail buying.”

Vishal Tripathi, research director at Gartner in India, says that while Lenovo has done well in the enterprise space with a strong brand like ThinkPad, which it inherited from IBM, its performance in the consumer space has been relatively weak. “Though they have created an impact in the hybrid tablets space with the Yoga brand, there is a lot to be desired from them in the consumer PC segment, where American brands like HP and Dell have done well,” he says.

The Indian market is becoming increasingly crowded with a plethora of Indian and international brands, as with the smartphone business in which some of the new Chinese entrants are selling feature-rich phones very cheap in order to build the market.

“It is a cut-throat business,” concedes Aymar de Lencquesaing, senior vice president at Lenovo Group and co-president of the company’s Mobile Business Group. “And probably the PC business is a good business for us to come from. We have survived and prospered in that business for decades with single digit margins and we have the credentials to be able to leverage that knowhow into the smartphones business, which is about scale and innovation.”

Future Plans

To give its PC business a shot in the arm, Lenovo is conducting an exhaustive market study. “We are trying to understand what kind of devices and user experience the Indian customer would like to see and how we can match their expectations,” says Gianfranco Lanci, corporate president and chief operating officer of Lenovo Group. “India is one of the few countries, like China, which has a potential customer base large enough for us to think of what products we can tailor-make for this region.”

Agarwal adds that Lenovo wants to drive PC penetration in rural areas, which it is evaluating like it would assess any new market, and is looking at a “solid plan” to achieve that. One innovation Lenovo is considering developing for India is a laptop that is “always connected” to high-speed internet, from the moment it is powered on, just like a smartphone, Lanci says. Also, to tap the burgeoning demand for low-priced smartphones with 4G capability, Lenovo, for the first time, is looking at developing a device that will be priced under $100.

All of this would, of course, complement the innovation already at work in Lenovo’s existing product portfolio. A case in point is the latest range of modular (also known as mod) phones, Moto Z and Moto Z Force, launched in October. These modular phones come with detachable back panels, with each panel enhancing certain features of the phone such as camera performance, battery life, audio quality or image projection.

“The concept is limitless,” says de Lencquesaing. “We have opened up the platform to outside developers who can write applications to build new mods or add on to existing ones. This is a step in the direction where the world is going—towards interconnected devices and the Internet of Things.”

Agarwal describes Lenovo’s journey in India so far as that of a bullet train. “Things have moved very fast,” he says. He would be hoping that the train gathers requisite velocity to reach the $6 billion sales target set by his global chairman on time.

Rahul Agarwal, MD and CEO of Lenovo India, says the journey ahead will be more challenging

Rahul Agarwal, MD and CEO of Lenovo India, says the journey ahead will be more challenging

Lenorola

Lenorola