Cognizant Technology Solutions: Far Horizons

Francisco D'souza is reinventing Cognizant, the role of the CEO and, if it all works out, the industry itself

In October 2009, one of our former colleagues Elizabeth Flock asked Francisco D’Souza a question: Which is the one book that influenced you the most?

Frank, as the now 43-year-old CEO of Cognizant Technology Solutions is known to friends, came up with an entirely clichéd answer. Built to Last by Jim Collins and Jerry Porras, he said. Because it provided him with a framework to establish a “cult like” culture focussed on core values. And that once this culture is in place, a firm doesn’t need personality-led leadership. End of the day, Collins and Porras argued, no single person in a firm ought to be bigger or more important than the team and its collective mission.

While it is not our intent to take anything away from a book many CEOs consider mandatory reading, we’d like to believe there was an earlier influence on him—that of the legendary French writer and aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. “A chief is a man who assumes responsibility,” Saint-Exupéry wrote. “He says I was beaten, he does not say my men were beaten”.

How else do you explain the motivation of a man who’s got the gumption to hand over everything he helped build over the years to his team, follow instinct, and throw himself into unchartered territory? In Frank’s mind, there seemed no other way to build a framework that puts everything at stake, including his own future and that of his firm. It isn’t the kind of thing most people we know of do.

Think about it for a moment. As early as August last year, a day after it had overtaken the formidable Wipro and was within striking distance of overtaking Infosys, we documented the atmosphere at Cognizant on our website (www.forbesindia.com). “...it means the company has a certain momentum, which to a large extent stems from its leadership....I’ve seen the same momentum in Infosys during the early part of the last decade when NRN Murthy had handed over the reins to Nandan [Nilekani]... Each time you visit the campus, you felt the air was charged with something. Cognizant gives you the same feeling these days. That is its most dangerous weapon.”

Like many people, we assumed the most intuitive thing for any leader would be to put all of their personal might into going for the kill and displace the incumbent—in this case, Infosys. But not Frank. His attention was elsewhere.

The world around Frank was changing at breakneck pace. His American customers, especially in financial services, healthcare and life sciences were talking a language peppered with words like cloud, mobility, social media, big data, and how all of these would change the landscape Cognizant was operating in.

Then there were people around him like Malcolm Frank, who heads strategy and marketing at the company, telling him that clients were facing dissonance in their organisations. Over the weekends, people were busy on mobile phones or tablet devices and connecting with their friends on social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter. But when they came into work on Monday, they were staring at enterprise applications built during another era.

When looked at from that perspective, clients were talking one language. But companies like Cognizant and their ilk were speaking in a different tongue. “Every one of our clients is trying to figure out how to make Monday mornings seem like a Sunday night. They were facing a crisis and we have to help them,” Malcolm says.

This was particularly critical for Cognizant, because its story is all about growth. On that count, it was doing pretty damn good. While everybody else in the business was growing on average at 18 percent, Cognizant’s pace was a furious 33 percent. But it came at a price in this case, lower operating margins. So, while everybody around was holding on to their purse strings, Cognizant awarded its people an average bonus of 150 percent. For every Rs 100 that its peers in the business earned in revenues, their operating profits were higher. Wipro, for instance, kept on average Rs 25 to itself, while TCS earned Rs 29 and Infosys Rs 36. Cognizant, on the other hand, could keep just about Rs 19-20 to itself.

“We are a revenue focussed company, our margins are lower than our peers, and when you have that model people get too focussed on growth,” says Gordon Coburn. “If you look at the landscape of IT industry, it is littered with companies that did so well that they went out of business.”

The evidence was there for all to see. Digital dominated the landscape during the minicomputer era. But it failed to prepare itself for a distributed computing world. When client service came of age, it looked like Cambridge Technology Partners would be the next big thing. But it ended up as lunch for Novell as the internet era dawned.

If he didn’t catch the next transition in time, Frank figured, Cognizant might meet the same fate. “I realised we hadn’t been paying enough attention to emerging technologies,” he says. As Saint-Exupéry wrote in his wildly innocent The Little Prince: What is essential to the heart is invisible to the eye.

“Intellectually we understood what needed to be done. If you lay out the case, any rational person will say it makes sense. The problem was when it came to day-to-day choices. If there is a choice between visiting an important client for existing business today or spending time on the new business, that is the moment of truth. Too often, you make the choice for the short term,” Frank said.

Theoretically, therefore, the most obvious thing to do would be that Frank focussed on the core businesses that got in all of the monies, while the best and brightest at Cognizant worked on building the future. If they fail, at least they would have tried. If they succeed, Frank and Cognizant would rest easy.

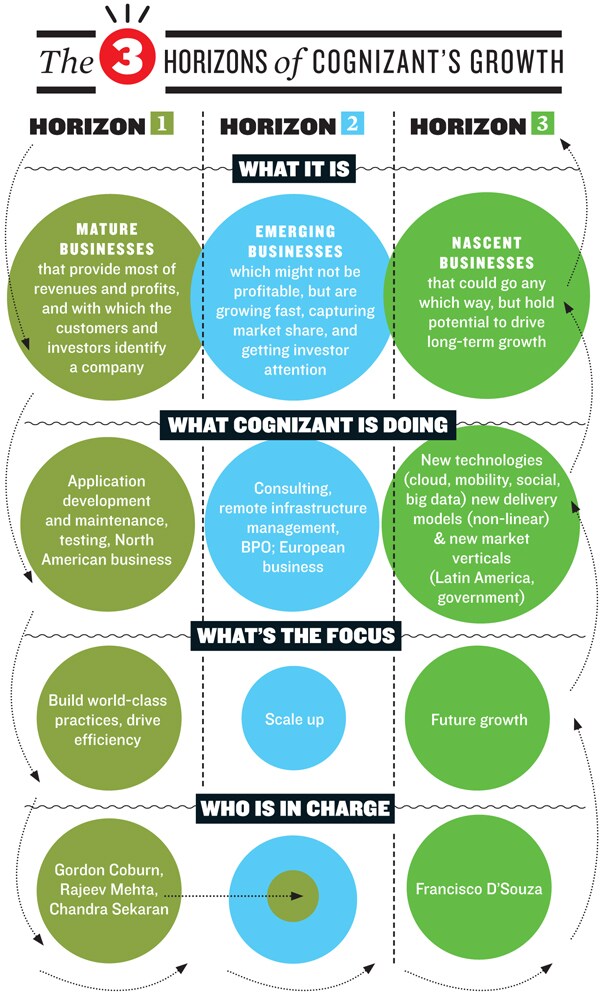

But Frank didn’t do that. Instead, he took a call that would make Jim Collins proud. Early in February this year, Frank formally announced that he’d made up his mind to relinquish charge of daily operations and focus instead on the future. Frank will, however, continue to lead Cognizant's overall strategy and direction. The here and now would be managed by a core team of three senior leaders—Gordon Coburn, Rajeev Mehta, group chief executive, industries & markets, and Chandra Sekaran, group chief executive, technology & operations.

The decision had everybody stunned. Says Viju George, executive director at JP Morgan, “It’s a bold move, (but then Cognizant has always adopted bold strategies to post industry leading revenue growth). Very few CEOs would have made this choice as it involves getting out of their comfort zone. But five years from now if this move of his doesn’t work, analysts would wonder if his time was better spent looking after the existing business and consolidating that further.”

The Kid

Frank was only 38 when he took over as CEO in 2007. Two years into the job, Cognizant, which draws 80 percent of its revenues from North America and 40 percent from banks and financial institutions, was hit by the crisis at Lehman Brothers. Most of his peers reacted by tightening their belts and cutting investments. But Frank did something else.

He asked his top team to convene in a hotel at Frankfurt Airport. He pored over every unit’s revenue and profitability numbers and then sent out a clear brief. The crisis was an opportunity and Cognizant wouldn’t cut down. Instead, it would invest in businesses for the future. Everybody would spend more time with customers, spend more on marketing, and invest in new businesses.

Frank told them that everybody, including him, would go out and meet every single one of their clients and partners. “I can’t tell you how many trips and how many plane rides we all took during those months,” says Mehta. “Clients finally stopped seeing us less as cost arbitrage providers and more as partners.”

Before Frank was asked to take over as CEO, he had spent time thinking around what it would take to build a consulting business at Cognizant. To his mind, that was the only way Cognizant could differentiate itself from competitors. The recession gave him the window to do just that. Clients were desperate to cut costs and increase revenues. Between 2006-11, Cognizant acquired four consulting companies, small tuck in acquisitions. And he got in Mark Livingston from AT Kearney to head the consulting business.

The efforts paid off. Today Cognizant has 3,000 consultants. Last year, it earned 5 percent of its revenue from the business. Consulting, which is embedded inside the various business verticals that Cognizant operates in, got 30 new clients for the company. It’s the kind of calls that have provided Frank and his management with confidence to look the current situation in the eye.

His world view is interesting. He believes the technology business doesn’t follow a straight trajectory. Instead, it follows an S curve. That means there are some years that are more important than the others. “In our view 2012 is a very important year, just like 1999 (when the internet era was born) and 1992 (when ERP was created). We are seeing a new IT architecture, no one knows what it is called as yet, but it will change this industry,” says Malcolm Frank.

Because nobody knows what lies ahead, last month Frank D’Souza formed a new business group called emerging business accelerators (EBA) with a simple mandate: Incubate new businesses around emerging technologies. The EBA now has 18 new businesses with Frank leading four.

Cognizant did not share how much revenue it expects EBA to bring in. “It should be able to get over $1 billion from these emerging business models by 2016, provided the market opportunity as seen today plays out,” says Viju George. At today’s run rate, that is only 15 percent of Cognizant’s revenue. Given that no one quite knows how long the emerging technologies will take to become mainstream, or what shape they will take, Frank is risking both his own reputation and career. But as Albert Einstein once said: Problems cannot be solved by the same level of thinking that created them.

Inside Cognizant there is near consensus that if anyone can pull this off, it is Francisco. Francisco D’Souza was born in Nairobi. His father, Placido was a diplomat with the Indian Foreign Service. Thanks to his father’s job, between him and his three sisters, they lived in 11 countries and went to local schools—not the international schools that his father’s colleagues preferred.

By the time, he landed up at Carnegie-Mellon University for an MBA, he had soaked in Asia, Africa, the Americas and Europe. “He was so international even then,” recalls Kinetic Engineering’s Sullaja Firodia Motwani, who met Frank as a student there. He was the youngest amongst a class of 220 students and his friends called him ‘The Kid’.

Unlike his classmates, Frank’s background was modest. He took up a job on campus to supplement his tuition fees. Rajeev Mehta, another classmate at Carnegie Mellon, says that it was common to see Frank pulling in all nighters to balance the demands of the intense course work and working.

“When class would get over, we’d all be hanging out, and you’d see Frank dozing off, take power naps for a few minutes and he’d be back.” Mehta, now Cognizant’s group chief executive, says Frank still works with the same intensity, pulling all nighters when chasing strategic deals.

“His youth and energy are a big advantage,” says Lakshmi Narayanan, Frank’s predecessor and now vice chairman at Cognizant. While at Carnegie Mellon, Frank dreamt of starting a technology company. But he couldn’t because he didn’t have the money. His requirements were more immediate. He needed a green card to stay back in the US and find a company willing to sponsor him.

That was when Dun & Bradstreet hired him. It had an extensive training programme where they put young recruits through three or four different projects. On one such rotation, Frank was in Germany and he heard about D&B’s plans to set up back-end IT operations in Chennai in association with Satyam Computer Services. He immediately called up Kumar Mahadeva, his mentor at D&B, and volunteered for the job. Mahadeva was the one who had convinced the folks at D&B to invest in the joint venture, then called DBSS.

There wasn’t much on the ground, and Frank had to start from scratch. It wasn’t an easy assignment. Frank was in his 20s and didn’t know too many people in Chennai. Friends say he would spend his evenings and weekends in the lobby of Park Sheraton, killing time watching people. When the rotations ended, Frank was bored and restless. He quit D&B for a while to take up a consulting assignment with an IT firm.

But Kumar Mahadeva lured him back. He had big ambitions both for the joint venture and Frank. By then, D&B had spun it off and it could now pursue non-D&B clients. It got Frank excited, because this was the kind of stuff he had talked about in business school. Cognizant was late to the party. In 1994, there were already 1,000 offshoring companies and nobody knew or cared for Cognizant. Not that it bothered Frank. He was raring to go.

The Innovator’s Dilemma

Call it serendipity, call it whatever you will, but Frank was priming himself to meet this moment for a long time. In the past, he’d read Clayton Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma closely and knew how tough it was for technology companies to get their act right in the long term—a phenomenon Christensen called the “technology mudslide hypothesis”.

At its core, the theory argues, established firms fail because they don’t keep up with hungry upstarts. At best, they’re always scrambling, and it takes a lot of upward climbing just to stay still. Any break from the effort, such as complacency born of profitability, causes a rapid downhill slide.

This is because their business environment does not allow them to pursue these opportunities when they first arise because they aren’t profitable enough. And investing in these businesses can take away resources from their existing operations which are needed to compete against existing competition. Inevitably, firms end up placing insufficient value on disruptors who could actually protect their future.

But start-up firms live in a different world at least until the time their innovation can invade incumbent networks. By the time established firms figure this out, at best they can only fend off attackers with a me-too entry, with little chance to thrive. The only reward instead is survival at best.

Firms that avoid this trap are the ones that keep a close watch on the environment around and the innovations they generate. But to do that, you need a framework to balance current and future priorities. Armed with this insight, Frank looked through several models to see what other companies had done in their business.

As he looked around, his eyes zeroed in on one firm that had managed to survive and thrive for over a 100 years. IBM. Frank was intrigued and decided to investigate. Most companies he knew could survive one transition, maybe two. But IBM was around for more than a century? What were they doing right?

As he spoke to IBMers, both past and present, he figured they were operating on something first proposed by consulting firm McKinsey called the Three Horizon Framework. It was based on research around how companies sustain a growth strategy over long periods of time. To do that, the model demands a company put its businesses into three buckets (see graphic).

Frank figured that while tough, it would also be the best model for Cognizant to implement. But to do it, he’d have to do three things.

Cognizant’s top management don’t sit in a single location. While Mehta was in Dallas, Chandra was in Chennai and Frank and Gordon were based in Teaneck, New Jersey. Every weekend, and on some weeknights, the four of them would get onto late night calls that ran for hours on end discussing how to implement the model given the nuances of Cognizant.

There were several questions on their minds. How to set up these new businesses without distracting from the core business? How to ensure each of the new businesses were supported by the existing ones? And who would lead each of these three horizons?

It was clear the emerging business would need a strong leader and the mantle finally fell on Frank. He was entrepreneurial, technology- savvy and it would send the right message through the organisation.

This done, Frank called in 35 people from his A-team—people who ran businesses and had P&L (profit and loss) responsibilities—to a two-day offsite in Florida. For the venue, he chose Fontainebleau, one of the grandest hotels on Miami Beach that had just re-opened after a billion-dollar transformation. He was anxious how the new strategy would be received by the group.

As he started presenting and announced he would be giving up on day-to-day operations to focus on the emerging businesses, the questions started coming in thick. What did it mean for the rest of them? Was he going to stay engaged? Several vertical heads had already built practices around mobility. Did it mean that they would lose those people? With his key team in tow, he started to answer all of these questions and get a buy-in from everybody at Cognizant. At the core of the division that Frank will drive now, is a venture capital firm-like structure, which would identify, fund and nurture new ideas and business opportunities. Frank picked some of the most entrepreneurial leaders from Cognizant to aid him, and each of them would be in charge of four or five business options, each run by a mini CEO. Vertical heads from the core businesses would not only guide these mini CEOs, they would also part-fund them.

Once the system is in place and running, Frank hopes to hand over the reins of the EBA to somebody else and pay more attention to Cognizant as one entity.

Like Cognizant, its peers like IBM, Accenture, TCS, Infosys and Wipro have invested significantly in new technologies. Accenture, for instance, has a new business unit, Accenture Mobility Services, which Gartner estimates has more than 2,500 dedicated professionals, and is expected to more than double next year. Closer home, TCS, Infosys and Wipro have made significant investments in emerging technologies.

“At this stage I’d say TCS is slightly ahead in this space followed closely by Wipro and Infosys. But it’s still early days and a level playing field,” says George of JP Morgan. He says TCS will earn at least $1.3 billion in revenues over the next four years from these emerging businesses and Wipro and Infosys could get $1 billion each.

Sanjay Purohit, senior vice president global head of products, platforms and solutions, Infosys, who leads a team of 5,000 people, says the hardest thing is to find the right white spaces, anticipate what a bank, for example, is going to look like five or 10 years from now and develop a product around that. There is a senior member from Purohit’s team inside every business vertical of Infosys. “Their salaries and bonuses are tied to how many of these solutions they are able to sell,” says Purohit.

Being a late comer to the industry, Cognizant has always had the advantage of learning from others. Its approach in the past has been to take time to assess the market, study the existing models, find a way to differentiate itself and put the entire strength of the organisation behind those pursuits. In short, it knows how to play the catch up strategy perfectly.

But this time around Frank doesn’t have that luxury. He will make mistakes, confront failure and success in equal measure and will have to learn from them the hard way. As Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, famously wrote, “You are responsible, forever, for what you have tamed. You are responsible for your rose.”

First Published: May 07, 2012, 06:57

Subscribe Now