On august 29, 2012, as jk shin, president of samsung Electronics, unveiled Galaxy Note 2, the second iteration of his company’s flagship ‘phablet’ smartphone series, in Berlin, a guerrilla shipment of 10,000 similar devices was selling big in stores across India. It had been brought in only a week ago.

Well, the devices were almost similar.

The Canvas A100 smartphones had 5-inch screens as against the 5.5-inch ones on the Note 2 but the resolution was not half as detailed the batteries were two-thirds the capacity the processors had just one core compared to the four on the Note 2 and RAM was just a fourth in comparison.

Then there was the price: Rs 9,999 compared to the Note 2’s Rs 39,900 at the time of its formal launch in India in November that year.

At 25 percent of the Note 2’s cost, the devices seemed to make sense to the Indian customer—so much so that in another three weeks, they would be all but sold out. This was the signal its makers, the Gurgaon-headquartered Micromax, had been hoping and waiting for.

Within days its supply chain, distribution and marketing machinery started shifting into attack mode. Specifications were mapped and orders sent out to China for a newer version featuring a dual-core processor, a better quality and higher resolution screen, more internal memory and an upgraded camera. The improved Canvas 2 was unveiled in the first week of November, a little over two months after its predecessor’s 10,000-unit test launch had proved successful: It still sported the Rs 9,999 price tag.

The phone turned out to be a winner for Micromax, selling out across many stores within days and commanding a premium over its retail price for nearly six months. Supply constraints certainly contributed to the instant sales (Micromax underestimated the popularity of the devices) but there was no doubt that the company was on to something significant.

“Our multinational competitors offered one or two smartphone models in every successive screen size—3.5 inch, 4.3 inch, 4.7 inch, 5 inch, etc. It was as though they were checking each [screen size] box with a few models,” says Rahul Sharma, 37, one of the four co-founders of the company and easily its most recognisable and dapper face.

So what did Sharma and Micromax do over the next year?

“From a Rs 6,000 Canvas Viva to a Rs 19,000 Canvas 4, we have put a 5-inch smartphone next to each of their boxes. We bet the house on 5-inch smartphones and that market just exploded!” he says.

Yesterday’s Scrappy Challenger Is All Grown Up

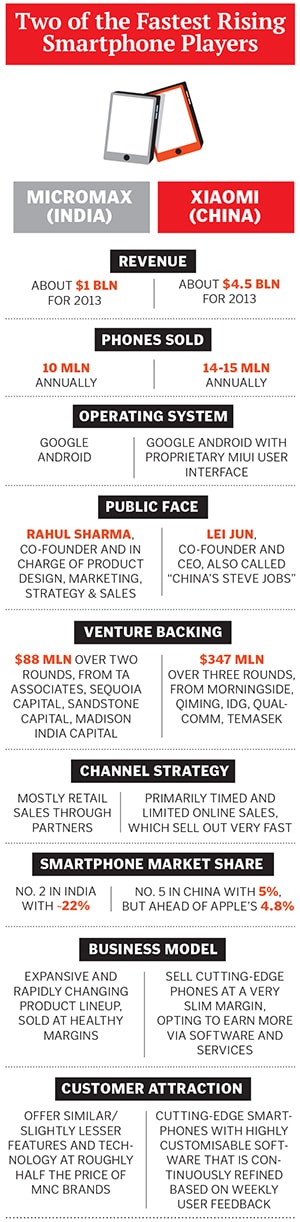

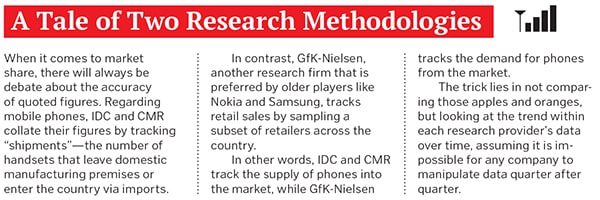

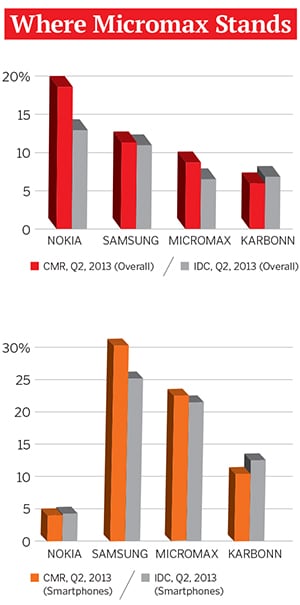

Micromax has come a distance since making its first mobile phones in 2008. According to research firms IDC and CyberMedia Research (CMR), the company is the third largest seller of mobile phones in India behind Samsung and Nokia.

The mobile phone market is currently going through a major upheaval as hundreds of millions of users in India and around the world upgrade from cheaper and less-capable feature phones to smartphones. In the smartphone race, both these research firms place Micromax firmly at the number two position behind Samsung in market share—22.7 percent versus Samsung’s 31.9 percent, according to CMR and 22.2 percent versus 25.7 percent, according to IDC.

Samsung India declined to speak with Forbes India for this story. A spokesperson said the company did not believe the IDC and CMR figures were accurate they were more convinced by the GfK-Nielsen numbers (a proprietary subscription service, the specifics of which Samsung did not disclose). “We do not consider Micromax a competitor,” the spokesperson added.

Sharma is amused when he hears that Samsung does not consider his company a competitor. “I think Mahatma Gandhi said it best: ‘First they ignore you, then they ridicule you, then they fight you, and then you win’!” he says.

And winning they are.

According to Sharma, Micromax has already surpassed last year’s revenue of Rs 3,100 crore in the first six months of this year. “We’re targeting one billion dollars by the end of 2013,” he says.

Vikas Jain, another co-founder, says, “In most countries where Samsung has a local subsidiary and has been in operation for over 12 months, they are usually number one. If we defeat them in India, this might become the first country where that stops being the rule.”

With its coffers filling up with revenues from the sale of over 2.5 million handsets each month, Micromax is setting its sights even higher. A stunning new global ad campaign featuring Australian actor Hugh Jackman was rolled out recently. The company claims it is spending Rs 30 crore on the campaign alone.

Gone is the diffidence and scrappiness of before. In its place is a belief that it can vault itself up the global pecking order of smartphones where the downslide of Nokia and RIM has left a vacuum. “Though it accounts for less than 10 percent of our revenue today, in three years we want our international revenue to be equal to our India revenue—or $2 billion each,” says Sharma. As with most Micromax senior executives, the line between confidence and bombast is blurred.

The Smartphone Rider

When Micromax crashed into the mobile phone market in India with its low-cost feature phones which had innovative attributes like dual-SIM and large batteries, it was dismissed as a one-trick pony. The arguments: They had no R&D they merely sold phones offered by contracted Chinese phone-makers in Shenzhen they were only about cheaper prices.

Perhaps the biggest contention was that as ‘dumb’ feature phones gave way to advanced smartphones, the likes of Micromax wouldn’t stand a chance. And yet, the company has not only made the transition, it has improved its ranking in the process.

Meanwhile, with only around 18 percent of Indian phone users using a smartphone, the upside of the shift in preference is still massive. In June, India pipped Japan to become the third largest smartphone market in the world after China and the US. By next year, it is likely to be the second largest.

The rise of Google’s free Android OS was easily the biggest factor that aided Micromax’s rise. In the pre-Android era, phones were compared and bought based on their hardware and software features. But Android almost completely took software differentiation off the table as both, a Rs 10,000 smartphone and a Rs 45,000 smartphone, carry nearly the same operating system (OS) features.

![mg_72765_micromax_280x210.jpg mg_72765_micromax_280x210.jpg]()

Being free, Android attracted most phone makers from across the world. And as volumes grew, it drew in more apps and their developers. A ‘virtuous cycle’ was created where users preferred Android phones due to the vastness of its ecosystem, and phone makers chose Android because users did. Nokia and RIM have struggled largely due to the diminishing appeal of their OS platforms for developers and consumers alike.

“What is surprising in the case of smartphones is the speed at which commoditisation is happening. In just six years, we have gone from the first generation of touchscreen smartphones, which seemed almost magical, to them becoming commodities,” says Horace Dediu, founder of mobile analyst firm Asymco, widely regarded as one of the foremost experts on smartphones and on Apple.

So far, this has worked quite well for Micromax.

“When a Samsung invests billions of dollars in R&D, it has to recoup that money. So while it comes up with its [custom-designed] Exynos processors, Micromax simply goes and buys Mediatek or Snapdragon processors. Buying what is available in the market is always cheaper than custom-building it,” says Katyayan Gupta, a technology analyst with Forrester Research.

Adds Ajay Sharma, the head of Micromax’s smartphone business who formerly led HTC India: “If I can make a smartphone that has everything that a competitor offers at double the price, why will consumers not choose it? Our Canvas 4 smartphone costs Rs 18,000, not Rs 45,000.”

This means that Micromax is riding on the slipstream of cutting-edge R&D being done by moneyed players such as Samsung and Nokia it is choosing to buy technology that is one generation old—and remember, a generation in the smartphone space is often measured in just a few months.

“The anxiety for larger companies is that if they build a new category—like, say, a tablet or smart watch—it gets commoditised in three years after it has, maybe, spent four to five years to design and develop it,” says Dediu. “If the market life of your product is shorter than its development life, then you have a problem. This is why Apple was so worried when Android copied its user experience early on—it happened so fast, before they had a pipeline of new [product] ideas.”

While Nokia, RIM and Samsung are caught in the ‘damned if you do, damned if you don’t’ dilemma, Micromax continues to claw at their marketshare by offering ‘good enough’ options for a fraction of the price charged by the ‘premium’ products. Neither can Micromax afford to play the billion-dollar R&D game like its bigger competitors, nor does it feel the need to follow the terms set by others.

How long can this continue?

Satish Babu, founder of Univercell, one of India’s largest mobile phone retail chains, says that while the average selling price for a phone in the country is Rs 5,000 currently, consumers are willing to spend 1.5 times that price at the point of upgrade. “And they are upgrading their phones every nine months today,” he adds.

Dediu believes that “when a technology product reaches commodity status, functionality becomes less important as it cannot be dramatically different across products. That is when marketing must change the message to other attributes like convenience, price or style.”

Yet, it is not impossible to differentiate your brand even within a commoditised space like smartphones.

“Apple’s approach has been to disrupt the market through technology, and once commoditisation sets in, to preserve a premium segment for itself. They did it with PCs and now they are doing it with smartphones,” points out Dediu. “There is a reason why they recently hired the Burberry CEO—clothing is the most commoditised category in the world, but even there you can still capture value at the premium end. Everyone doesn’t wear $3 T-shirts and even the Chinese, who make those T-shirts, aspire for European brands.”

The rationale for Micromax’s ballooning marketing and advertising spend is readily apparent now. Since features and hardware specs cease to be differentiators, it needs to build a brand that can compete with a Samsung, one that consumers can aspire to.

“Even folks in Faridabad and Gorakhpur will know Hugh Jackman. Eventually they will think of us as a high-end brand. We want to be a Zara or a Mango not a Peter England, but not a Gucci or Prada either,” says Rahul Sharma.

Target: Samsung

Though the stated objective of most Micromax executives is simply to grow the company’s revenues and customer base in India, there is a certain unsaid ambition that seems to unite them—to unseat Samsung as the leading smartphone player.![mg_72767_micromax_position_280x210.jpg mg_72767_micromax_position_280x210.jpg]() “Beating Samsung is not going to be easy. The Koreans have good designs and innovations in each product, a good service and distribution network and solid market knowledge. Plus, they can really be aggressive,” says Babu of Univercell.

“Beating Samsung is not going to be easy. The Koreans have good designs and innovations in each product, a good service and distribution network and solid market knowledge. Plus, they can really be aggressive,” says Babu of Univercell.

Micromax’s biggest weakness so far has been the perception that its phones aren’t very reliable, and getting one serviced is a pain. “Micromax phones are not bad in terms of quality. Even Samsung and Nokia phones have issues, but the companies are able to resolve them quickly. On the other hand, Micromax has had challenges in responsiveness because they didn’t have enough service centres,” says Babu.

To address this, the company is nearly tripling the number of its partner-managed service centres from 436 last year to 1,250 by March 2014 (currently they are at 745), says Bharat Malik, Micromax’s service head (who was hired from Nokia). Across these centres, Malik’s team of 200 claims to oversee 6,50,000 customer walk-ins every month.

It wants to reduce the turnaround time to less than seven days from the current 15. “To do that we are transitioning to holding spare part inventory instead of the earlier Just-In-Time ordering system,” says Malik. A new CRM system will go live before the end of the year.

“Service is one area where we need lots of improvement,” says Sharma. Senior executives have been reading case studies about companies with impeccable service offerings, such as Domino’s Pizza for instance, he adds. “Like Domino’s 45-minute delivery guarantee, can we move towards, say, a 48-hour repair guarantee? We are piloting a home pick-up and drop of our phones in Mumbai and Delhi. We would like to roll this out in a bigger way in six months,” he says.

On the retail front, it is trying to formulate a bottom-up, direct-to-retailer approach supported by brand advertising instead of trying to emulate the strong channel relationships nurtured by the deep-pocketed Nokia and Samsung.

Through its ‘Elite Circle’ channel promotion initiative, it tracks the sales of its phones directly from retailers on a daily basis (through a proprietary SMS-based app) instead of waiting up to weeks for that data to flow in via multiple distributors levels. Depending on how they fare against the sales targets, incentives get wire-transferred directly to retailers.

Then, of course, there is the product portfolio.

Since its inception, Micromax has been known for two things: An uncanny ability to spot product gaps in the market, and the speed with which its supply chain responds to them. While both of those still stay valid, its scale now gives it a direct seat across the table from global ecosystem biggies ranging from Google to Intel to Qualcomm to MediaTek.

Sharma’s aspiration to be seen as a Zara (the Spanish fashion giant that launches 10,000 new designs every year, with some going from design tables to stores in as little as two weeks) is as much about the responsiveness of his supply chain as it is about the attributes of the brand.

“Everyone has to act like a CEO of their own domain and take quick decisions. Our culture is to be quick and nimble. Thus, a wrong decision is often better than no decision at all,” he says.

Micromax’s Canvas HD smartphone was the first product globally to use MediaTek’s quad-core processor. Later this year, it will be another Micromax phone that will sport MediaTek’s first octa-core processor too.

Another American semiconductor giant is said to be offering it an India-specific LTE chipset instead of the off-the-shelf ‘multi-mode’ ones that support all global frequency bands. This, in turn, will allow it to bring a 4G smartphone to the market at a significantly lower cost than what currently exists.

Sharma is also insisting that global hardware and software makers treat his Chinese manufacturing partners—Tinno and Longcheer—as extensions of Micromax. In response, the world’s best known PC processor company has already embedded its engineers within these firms to help in the joint-development of products, he says.

Through these tightly-coupled partnerships, Micromax reckons it can react even faster than Samsung or Nokia which are vertically integrated. “Supply chain speed is a factor of your mind, not of your backend capabilities,” Sharma says.

A good example of this would be how the company reacted to Nokia’s Asha series of feature phones that use the older Symbian Series-40 operating system. (Nokia insists these be called smartphones, but most analysts dispute that. “Let the company say what it wants to but Asha is not a pureplay smartphone. At best, it is a ‘smart feature phone’,” says Forrester’s Gupta).

“After Nokia launched Asha, Samsung got edgy and launched its own feature phone line, Rex. We debated whether to launch our own feature phone sub-brand. But then

we checked if we could get Android to run on just 256 MB of RAM which an entry-level phone might sport. It did, but games like Angry Birds and Temple Run didn’t,” says Sharma. “My own R&D team advised me against it but if Google allows me to run Android on 256 MB of RAM, why can’t I? So, in two months—not a year—we launched our Bolt series of entry-level Android smartphones priced between Rs 3,500 to Rs 6,500. It turned out to be a huge success and we are selling around 5,00,000 units every month.”

Running Android on lower-end phones appears to be a strategic priority for Google, given its work on the latest Kit Kat version to ensure it can run smoothly on phones with just 512 MB of RAM. “For 2014, our goal is [to figure out], how do we reach the next billion people?” Android head Sundar Pichai said at a company event on October 31 in San Francisco.

“Micromax seems to be seeing an opportunity and executing its strategy well. I see local players like them having the potential to disrupt Samsung. The problem for Samsung is that they need to constantly reinvent what they do. Take Nokia, for instance—from gaming and media phones to music and email as a service, it had strategic ideas for well over a decade, and in all directions,” says Dediu. “Plus they had their own platform [unlike Samsung, which relies mostly on Android]. Very few companies historically have had the ability to ‘self-disrupt’ and cannibalise their own business. Does Samsung have what it takes when Nokia, HP and Sony didn’t?”

Chefs and Cooks

Micromax, as a company, was formed in 1991 by Rajesh Agarwal. He was joined by Rahul Sharma, Vikas Jain and Sumeet Arora (all engineering college mates) as equal partners in 1999. For nearly a decade, the firm sold software, telecom services and computer hardware to enterprises till, in 2008, Sharma convinced the others to branch out into the mobile phone space. Their first phone, the Rs 2,150 X1i, touted a battery life of nearly 30 days and was a big success in rural India. They went on to dual-SIM, a feature which would emerge as their breakout hit and establish the company as a serious player. As sales started skyrocketing, people began to take note. Private equity firm TA Associates invested $45 million in early 2010 while Bollywood actor Akshay Kumar came on board as its brand ambassador.

Most of its homegrown peers are primarily and, in some cases, entirely, founder-led. Micromax, on the other hand, has used its scale and success as a trigger to induct senior industry leaders into executive positions in the company.

Deepak Mehrotra, an ex-Airtel executive, had been playing the role of CEO for the last two years. (While Forbes India was still reporting on this story, Micromax informed us that Mehrotra had quit for personal reasons. It would later turn out that he had joined global education services company Pearson as its India head.)

Ajay Sharma, the former head of HTC India, heads the smartphone business. Amit Mathur, the former head of sales at RIM India, leads the international business. Bharat Malik took over the service vertical after joining them from Nokia. Sony Ericsson executive Khaja Muzaffarullah came on board as the driver of the still significant feature phone business while former entrepreneur Shubhodip Pal became the chief marketing officer.

Meanwhile, the founders have taken on more strategic roles in the company. Sharma is clearly the one making the biggest bets. He says he decided to appoint Hollywood bigwig Jackman as brand ambassador even though a company dipstick revealed that nearly eight out of 10 customers had not heard of him.

“The standard approach would have been to pick someone who is popular among 80 percent of the customers. But I said we need to influence the 20 percent who really matter—the opinion makers and influencers,” he says.

Earlier this year, he also enrolled at Harvard Business School (HBS) for its owner/president management programme which trains business owners and entrepreneurs over a three-year period to become better leaders. The trigger, he says, was when the HBS academics had visited Micromax to compile a case study on it. “As they asked us questions for the case study, I had my own questions for them, including whether we should go global or continue expanding in India,” he says.

Unfortunately, a week into the programme, he had to rush back after one of the co-founders, Rajesh Agarwal, was arrested by the CBI for allegedly bribing officials for a real-estate transaction.

Agarwal has since resigned from the company.

“The divide between the founders and professionals is this: They manage all the day-to-day operations while we handle the strategic elements,” says Sharma. “I handle products, strategy, marketing and sales without getting into things like retail or channel strategy. Sumeet [Arora] looks at after-sales and IT infrastructure without getting into, say, what specific spare parts need to be ordered. Vikas handles all our relationships with operators and closes big deals before passing them on to operations. And finance, which was handled by Rajesh, is now split between the three of us who have always been hands-on.”

While on paper this division of responsibilities may look sensible, four co-founders and five business heads may be a case of too many cooks unless Micromax can continue to grow at a breakneck speed for the foreseeable future.

Going international, therefore, becomes imperative.

From India, With Love

The walls of Amit Mathur’s cabin at Micromax’s Gurgaon headquarters are plastered with maps and posters. Among them are maps of Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, peppered with red, black and blue dots and stars, each representing a retail or service presence. There is a smaller one of Moscow too. There are Sinhala (an ethnic Sri Lankan group with its own language) posters as well, for two of its entry-level phones.

Mathur himself is in Sri Lanka, busy consolidating the company’s position. During a telephone conversation, he says: “In Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka, we are the number two player six to eight months ago, we weren’t even in the top five.”

This is Micromax’s second attempt at going international. Its first forays, two years back, ended mostly in failure when consumers in Latin America, Africa and the Middle East didn’t quite take a fancy to its feature phones.

“Feature phones often require customisation, which becomes a hassle when they are being sold across multiple countries. We were prudent enough to pull back and consolidate,” says Mathur. “When I joined in January, we decided our gameplan would be to strengthen our presence within the SAARC countries. We could leverage our existing advertising because most [television] media plays there too.”

And its Bolt line of entry-level Android smartphones can be targeted at newer markets far more efficiently than feature phones. “Android has removed customisation as a hurdle for us,” says Mathur.

![mg_72769_micromax_smartphone_280x210.jpg mg_72769_micromax_smartphone_280x210.jpg]()

Next up are Myanmar, Russia, Romania and Ukraine. Like India, these markets too have low smartphone penetration and are gradually shifting towards retail sales (as compared to the operator-subsidised model in many western European countries and the US). Micromax is assuming that as consumers are forced to pay retail prices for their phones, they will tend to place less of a premium on brand and more on value.

“In Russia and its neighbouring countries, the biggest challenge, often, is the language. Not in terms of phone customisation, but as far as communications is concerned. Nokia used to have a good presence but that is reducing… so that is a plus,” says Mathur. “But Samsung is trying to take over its share, so you have to fight them. In some cases, there are strong Indian brands like Fly too.”

Dediu points out that “there is nothing wrong with an Indian company aspiring to become a global brand. After all, we have seen companies from Japan and Korea do it earlier and, later, China. The emergence of Asian brands is the big cultural phenomenon of this century.”

Only the Paranoid Survive

Till this point, Micromax’s strategy has been to spot significant market opportunities left untapped by bigger competitors, for instance, the dual-SIM market by Nokia or the 5-inch ‘phablet’ space by Samsung.

But those gaps are getting harder to find. “Cheaper prices alone will not be sustainable because other players are launching inexpensive devices. Do you think Microsoft [which now owns Nokia] will not aggressively price Lumia devices below Rs 10,000?” says Forrester’s Gupta.

There is also the blind spot that comes from being a marketing-driven innovator, when your customers cannot tell you what they want because they cannot imagine what they want. “How will Micromax spot the next generation of technology that may be portable or wearable? Maybe instead of a larger screen there will be no screen at all. How will they compete?” says Dediu. Given the pace of innovation and competition in the smartphone space, his questions ought to worry Micromax.

By way of answer, Sharma talks about two of his yet-unreleased potential blockbusters, neither of which is a remainder of a competitor’s strategy.

The first is a hybrid device that combines two vastly different products into one. Yawn, you probably think. Haven’t those been around for a couple of years now?

Not like this one: It features two full-scale and side-by-side operating systems and chipsets—a global first. “I want to attack the IT industry from the sidelines,” he says, refusing to reveal the name of this product.

Another creation he shows is a full-featured smartphone with a battery life of seven days—wishful thinking when today's smartphones need to be charged multiple times a day. “Even then, mobile phone hardware is going to become like PC hardware. It is commoditised—what else can you add now?” asks Sharma.

Like the PCs got eaten up by the tablets and smartphones of the “post-PC world”, so too will smartphones one day. What then?

“Why can’t we build the next Flipkart without replicating their backend infrastructure? I have got millions of customers, many of whom use 5-inch devices which are great for shopping. We are figuring out how to sell them products though for example, a white-labelled e-commerce site whose fulfilment is handled by someone else and I get a cut out of every transaction,” says Sharma. “Customers, on the other hand, will want to use Micromax phones because they get exclusive offers and services.”

He claims to make close to Rs 100 crore annually by charging developers for downloads and exclusive apps on Micromax’s proprietary Android store (which coexists with Google’s Play Store on its phones).

“We are working on an app that can translate a conversation from English to Hindi in real-time, as it is being spoken. We are working on our own currency so we don’t need to rely on operator billing. We want to buy software companies,” says Sharma. “In the next five years, our software division will earn more than the hardware. The future lies in the internet—I’m 200 percent convinced of that.”

“Beating Samsung is not going to be easy. The Koreans have good designs and innovations in each product, a good service and distribution network and solid market knowledge. Plus, they can really be aggressive,” says Babu of Univercell.

“Beating Samsung is not going to be easy. The Koreans have good designs and innovations in each product, a good service and distribution network and solid market knowledge. Plus, they can really be aggressive,” says Babu of Univercell.