Can Flipkart Deliver?

India's top e-commerce website is betting big that "customer delight" will lead it to success. But costs and management issues could play spoilsport

Let’s put it this way. Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal have audacity and balls.

If you think of these as virtues, what you get are friends who grew up together, studied at the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi (IIT-D), are now around 30, and in five years built Flipkart, India’s largest e-commerce company.

This financial year, they expect to show investors Rs 2,500 crore in revenues, a 400 percent growth over last year’s numbers. They sell 17,500 items each day—or 6.5 million items annually. Nearly 5,000 people, including contractors, work for them. Their closest competitors make do with 700-800 people.

But if you’re the kind who think of audacity and balls as the foundation on which hubris and foolhardiness are built, then Sachin and Binny Bansal’s Flipkart begins to look like an entity skating on thin ice. What lends credence to this view is that it is shared by General Atlantic Partners, the world’s 12th largest private equity firm with over $17 billion in investments.

The view was cemented late last year when Sachin and Binny travelled to New York with a single point agenda: Convince General Atlantic Partners’ investment committee to invest $150-200 million into Flipkart at an overall valuation of somewhere between $750 million to $1 billion.

After three rounds of meetings with multiple committees, including ones with Martin Escobari, a managing director at the firm specialising in online commerce, and William Ford, the CEO, they all declined. Why? They couldn’t understand all of Flipkart’s accounting strategies or its numbers. How much, for instance, was it using shareholder’s equity to fund operating losses? Just what was the true cost of ‘returns’ for the company?

More importantly, they figured that at the pace at which Flipkart was building Infrastructure and adding people, it would need at least $2 billion in annual sales to just break even. Getting to that number, they argued, would take an awfully long time given where Flipkart was back then.

Though it remains unstated, Flipkart’s goal is to be the Amazon of India. But that may be a chimera. Amazon relied on the funds from its 1997 initial public offering (IPO) to tide through the aftermath of the dotcom crash that took out most of its rivals. Without competition, it could afford to lose money on building infrastructure. It would take $2.8 billion in losses over six years before it declared its first quarterly profit in January 2002.

When faced with these posers, Sachin and Binny didn’t have answers. They took the flight back home to Delhi. Disappointed, they had no option but to go back to their existing investors: Tiger Global, their long time sugar daddy, and Accel Partners.

Hedge fund Tiger Global and Accel too had been looking forward to the deal, because that would significantly increase the value of their own Flipkart stakes.

Sources say even the term sheet the Bansals carried with them to New York was drafted by Tiger Global. Now that Sachin and Binny were on the back foot, they were told Flipkart was, at best, worth not more than $500-600 million. And that $100 million was the best Tiger Global and Accel could put on the table right now.

Flipkart refused to comment on any of its investment deals or discussions.

When Flipkart was founded in 2007, it was on the back of a fanatical promise. Whatever be the cost, delight customers. Starting with books, a market it upended in little time, Flipkart started to offer CDs & DVDs, mobile phones, consumer electronics and more recently, healthcare and beauty products. Their fanaticism won over two million sceptical Indians.

To get them to Flipkart, though, the Bansals invested venture capital funds into infrastructure that could support customer service, last mile delivery, warehousing and technology. They spoilt their customers silly by offering them the option to pay cash on delivery (CoD) if they didn’t have credit cards or were uncomfortable using them online, heavily discounted prices, free delivery and later, no-questions-asked returns.

It was a model they’d imported from their multiple visits to China, a country which they thought had problems similar to India: Large population, poor transportation, low penetration of modern retail, unreliable third-party logistics and few credit card transactions. Chinese e-commerce vendors had gotten around the problem by creating infrastructure around each problem.

Flipkart thought that was the way to go. Instead, they were gobsmacked by even worse ones. With CoD, cash flows are controlled by courier companies. It takes weeks to reconcile accounts and they charge fat fees as well. To get around this, the Bansals started their own courier firm.

But as the division grew, they realised efficiencies could come only if deliveries from warehouses were streamlined. But to do that, inventories ought to be in stock. Meanwhile, thanks to CoD, fickle customers often changed their minds at the time of delivery, in turn leading to growing returns.

That posed an altogether unexpected question. How do you fund the delivery and logistics business? The solution: Flipkart Logistics, an initiative that started off as a pilot in December 2010 to handle the company’s in-house orders, but would grow over time to become a platform that could offer warehousing, packaging, delivery and CoD to any company for a fee. (Flipkart denies it was ever a consideration).

Today, with over 60 percent of Flipkart’s 4,800 employees spread across 40 cities, Flipkart Logistics is the tail that wags the dog. The food that sustains this growing entity is inventory. Book distributors talk of Flipkart buying books from every single title in their catalogue. They were surprised, because many of those titles hadn’t sold in years.

A category-wide 30-day returns policy and aggressive inventory acquisition put more pressure on the system to handle returns. At least three industry sources claim the company has attempted to return 30-40 percent of books they had bought a year ago to a few distributors when the norm in the business is 10-15 percent.

In mobile phones too, where most of its peers prefer close back-to-back arrangements with distributors, Flipkart prefers to hold its own stock. Some distributors are now complaining of delays in payments. Flipkart maintains these delays are because the software it uses to maintain financial records are being updated.

On February 9, 2012, everybody, insiders included, was taken aback when Sachin Bansal announced Flipkart’s acquisition of Letsbuy.com. A rival e-commerce website, it sold consumer electronics. He said it would allow Flipkart build a dominant share in the space.

Since the time it started operations in 2009, Letsbuy deployed heavily discounted prices and extensive product catalogues as strategies to acquire market share. By January 2011, it had enough heft to convince Helion Venture Partners, Accel Partners and Tiger Global to invest $6 million.

But it burnt nearly all of it in less than a year. By the end of the year, it started knocking on investor doors for a fresh round of funds. Nobody uttered a peep. Instead, co-founders Hitesh Dhingra and Amanpreet Bajaj were told by Tiger Global and Accel to sell their business to Flipkart. From an investor’s perspective, it made no sense to fund two companies competing in similar spaces. The Bansals were told much the same thing and had no option but to acquiesce.

In a few months, practically all of Letsbuy’s 350 employees were quietly let go and its infrastructure, including the warehouses, dismantled. Accel and Tiger Global, however, salvaged all of the cash investments in Letsbuy and got additional stock in Flipkart.

“This was a great business decision and we stand by it. Tiger had nothing to do with it,” says Karandeep Singh, Flipkart’s CFO.

All of this, in turn, raises a question: “Who owns Flipkart?” People privy to the financials say Tiger Global is the largest shareholder in the company and owns at least 40 percent on a fully diluted basis. Add to this Accel’s stake and you’re left wondering how much the co-founders Sachin and Binny Bansal actually own. “Flipkart today is an investor-owned and investor-driven organisation,” says Tapan Kumar Das who was the company’s vice-president, finance, for a year until April 2011.

It’s interesting how things got here. Towards the latter part of 2009 when monthly sales were in the region of Rs 1 lakh, Abhishek Goyal, an associate at Accel Partners, noticed Flipkart and put it on the firm’s radar.

Sachin Bansal, who by then was clearly the company’s brains and CEO, demanded the company be valued at Rs 16 crore. Venture capitalists balked at the figure. Much dithering later, Accel invested nearly $1 million (Rs 4 crore then) in the company, but in two equal tranches. Accel’s Rs 2 crore into Flipkart’s bank account was a personal victory for Sachin.

The funds were deployed immediately and the results were spectacular. Monthly sales skyrocketed and with them, Sachin’s expectations. He started to look at Accel’s $1 million as chump change and initiated conversations with others as well.

Even as many were evaluating and debating, Lee Fixel, a managing director with Tiger Global, a deep pocketed and canny hedge fund, swooped in to invest $10 million at a valuation of Rs 220 crore. The speed at which it happened blindsided everybody, including Accel, which until then had invested only 50 percent of what it had originally committed to. Left with no choice, it was forced to invest the remaining amount at a much higher valuation before getting relegated to the backseat. This, because it didn’t have the muscle to write cheques of the kind a hedge fund could. It chose not to participate in Flipkart’s second and third rounds of investment, leading to a further dilution of its original stake.

At Tiger Global, the 29-year-old Fixel was closer to the Bansals in age and outlook. “Our philosophy was to find investors who don’t want to run the business and the biggest thing Tiger brings to Flipkart is independence and belief in the management,” says Binny Bansal.

Tiger Global was started in 2001 by Charles ‘Chase’ Coleman as one of the numerous “baby Tigers” founded by the alumni of Julian Robertson, legendary investor and founder of hedge fund Tiger Management. Its investment sweet spot is the phase between the first venture funding for a startup and it going public. So, it prefers to let local venture capitalists spot promising companies by making the first investment, before opening its purse strings.

Some call it investing in regulatory arbitrage, because it allows Tiger Global to acquire stakes, understand the real metrics of private companies, and then sell them to the public through an IPO just before that advantage disappears.

There are precedents to this where Tiger Global investments “pop” on the day of the IPO, only to fall back to more realistic levels. These include Youku.com (the YouTube of China, down 35 percent), Yandex (the Google of Russia, down 49 percent), DangDang (the Amazon of China, down 79 percent) and Gushan Environmental Energy (Chinese biodiesel producer, down 96 percent).

Some of its investees have turned out to be much worse. Trading in China’s Longtop Financial Technologies was suspended by the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) after an accounting fraud. This is not to suggest Tiger Global makes only risky investments. It has invested large amounts in high-profile companies like Facebook, LinkedIn, Apple and Google.

But when companies have to deal with conflicts of interest, it is usually the board that asks hard questions. According to Flipkart’s official filings, the only other person on its board—other than the Bansals, Accel’s nominee Subrata Mitra and Tiger’s Fixel—was Rajesh Magow, CFO of online travel company MakeMyTrip.com.

But Tiger Global owned nearly a fifth of MakeMyTrip when Magow was inducted into the board. Magow chose not to respond to a request for an interview. Sachin Bansal declined to talk as well about the composition or function of Flipkart’s board. It is “a private matter,” he said.

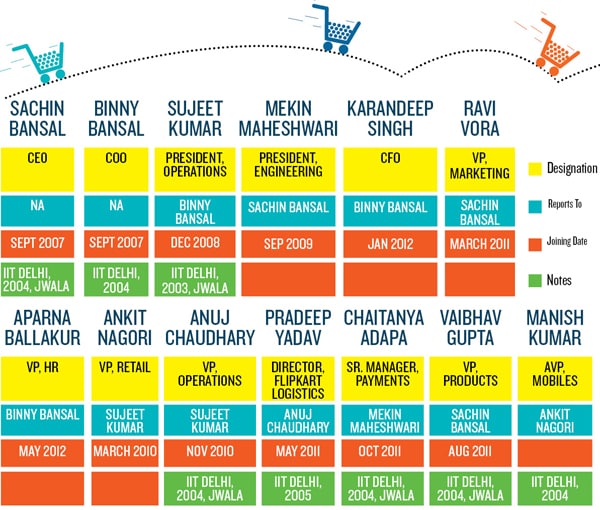

The schisms at Flipkart run deep and offer lessons on how not to expand a well-funded startup. In December 2009, after its second round of funding that got Flipkart Rs 50 crore, Sachin and Binny embarked on a series of hires to man key functions like finance, category management, marketing and human resources (HR).

Vasudha Mangalam came in from a technology company to eventually lead HR. Vipul Bathwal, a 2008 IIM Ahmedabad graduate, came on board to identify newer categories. Satyarth Priyedarshi, a former head of merchandising for the Borders bookstore chain in Dubai, was roped in to head buying and merchandising. Tapan Kumar Das, the erstwhile finance head at venture-funded salon chain YLG, joined as VP, finance, along with Anupama Sharma, a Stanford Business School graduate who would lead marketing. Within a year, all five quit.

Soon after Vipul Bathwal came on board, he identified mobiles as a category and launched it in July 2010. This was the company’s first big category expansion after books and CDs/DVDs.

Within the first quarter, sales rocketed to around 30-40 percent of Flipkart’s overall revenue without marketing support.

Sitting in Delhi, Sujeet Kumar, the head of Flipkart’s operations, nervously studied the rapidly growing mobile category and its implications on power equations at the firm. Kumar was a year senior to both Bansals at IIT-Delhi and more importantly, a fellow-resident of Jwalamukhi hostel with Sachin.

“Jwala”, as it was called, was one of the 10 student hostels on the IIT-D campus. Unlike many other IITs where students changed hostels during their four-year engineering stay, IIT-D insisted they stay in the same one. This helped forge close networks and deep bonds that often lasted a lifetime between residents. Allegiance to a particular hostel meant friendships with others from a rival hostel was frowned upon. “We hated the sight of anyone from Niligiri [one of the hostels],” says a person from the same batch as the Bansals, and an erstwhile resident of Jwala. “The first thought that crossed our minds when we came upon one was to bash him up!”

It was in this testosterone and allegiance-driven community that Kumar found his true calling. Though from the unglamorous civil engineering stream, he was politically active on the IIT-D campus. Working tirelessly behind the scenes, often over tea, cigarettes and alcohol or long sessions of card games, Kumar would broker deals and negotiate allegiances to further Jwala’s causes. As opposed to him, Sachin was an introvert who preferred to spend most of his time within his room. Which is perhaps why soon after starting Flipkart, Kumar was one of Sachin’s first key hires.

Flipkart’s logistics were a natural foil for Kumar, playing to his inherent skills with numbers and people “management”. As he scaled Flipkart’s back end operations, Sachin’s trust in him grew. Soon, Kumar started to get in newer people like Maneesh Mittal and Anuj Chaudhary into the team, all from his network at Jwala. “Sujeet built his operations team with people he trusted. That was at a time when Flipkart was very small. So, it was easier for him to get people he knew from Jwala,” says Binny.

Together with the Bansals, they banded together as a secretive bunch that decided which way things went. “They would talk and share information only with each other. There was no openness in the system,” recalls Das. That perhaps explains why Flipkart did not have a formal stock option programme till late 2010 when it commissioned ESOP Direct, an Indian specialist firm, to design the first version. Only a handful of loyalists were given stocks till then.

An ex-employee recalls asking Sachin about consulting with a professor from IIM Ahmedabad known for his expertise in helping startups scale successfully. “Those IIM guys will just steal our ideas!” was Sachin’s response.

It was this mindset that eventually contributed to Bathwal’s fall. Sujeet Kumar detested the outsider and the thought of being sidelined was terrifying. So, Kumar started digging to find Bathwal’s Achilles heel. He struck pay dirt when he stumbled on the fact that in his eagerness to grow the category, Bathwal had aggressively bought large inventories of mobile phones from distributors.

How much inventory to hold is one of the toughest questions retailers deal with. Having thin stocks carries with it the risk of turning down orders too much of it and there’s the risk of unsold goods. But Bathwal reasoned he was better off with larger inventories because Flipkart’s stated mission was to delight customers. Instead, he found himself staring at large inventories—a problem Flipkart was intimately familiar with as well.

But with this information on hand, Kumar called Bathwal on the phone and told him “You have a dead stock situation.” Bathwal protested. “We can return it to the vendors.”

A few days later, Sachin and Binny Bansal called him for a meeting. “Sujeet is now going to head all our categories and doesn’t want you to report to him. I’m sorry, but he is my senior from IIT-Delhi,” said Sachin. A week later Bathwal put in his papers. It was much the same thing with the others. The Bansals trusted only their investors and a handful of colleagues from their IIT days. The others were dispensable outsiders.

Das says he was frustrated after being stonewalled every single time he tried to get clarity on the finances. In spite of heading the function, he was unable to find accurate numbers on sales volumes. In one instance he found Anuj Chaudhary, another “Jwala” alumnus, had hired a finance person into his division without so much as informing him.Then there was Mittal, an aggressive and abrasive “Jwala” alumnus, with a take-no-prisoners approach. “Five to 7 percent of the book sales were based on cash. I wanted to know from Mittal why vendors wouldn’t accept cheques. But I got no answer. It’s possible Sachin and Binny didn’t know about these deals though,” says Das.

Mittal, we were told, was on a sabbatical when a request for his version of the story was placed. Two weeks later, Mittal was taken off the rolls. No reasons were provided.

Das adds he also found a mismatch between Flipkart’s sales receipts and bank balances in his early days. Ernst & Young’s 2011 annual audit report of Flipkart’s accounts had also raised at least two “qualifications”. Qualifications in audit parlance refer to notes or comments made by an auditor indicating their displeasure with something in a company’s books. In Flipkart’s case, the qualifications were around the company’s internal control and reporting systems. It is not known if those qualifications, or others, were present with the next year’s accounts.

“Back then the company was growing so rapidly that it’s possible there may have been some lag between the two,” says Sachin in Flipkart’s defence.

Das says he resigned in April 2011 before having to put his name on Flipkart’s balance sheet for the year gone by. “If I had to put up with so much of pain around finance, I might as well have done it for my own company than as an employee for Flipkart,” he says.

“Are you going to put Das’ name next to all these allegations?” Sachin asks me during an interview in which Binny and CFO Karandeep Singh were present.

“Yes,” I tell him.

“Hmm!!! Usko toh dekh lenge [We’ll deal with him],” he says to Binny, before being pacified by Singh to let matters rest.

“An IPO will be an unnecessary evil for us. Today, there is so much of private capital available that we’d like to stay private for as long as possible, like Facebook,” says Binny Bansal. But truth is, Flipkart started evaluating its options way back in 2010 by first studying the regulatory environment in the US, Mauritius and Singapore. Listing in India was out of the question, given SEBI’s regulations around generating profits first.

The appointment of MakeMyTrip CFO Magow to Flipkart’s board is probably the best indicator of how its IPO will pan out. Magow was the architect of MakeMyTrip’s US IPO using a holding company structure based out of Mauritius.

Last year, Flipkart floated a company in Singapore, Flipkart Private Limited, which spent Rs 323 crore earlier this March to acquire shares in Flipkart India Pvt Ltd, a subsidiary company incorporated only in September 2011. It’s hard not to consider that as part of the run-up to an IPO next year. But it will raise questions the Bansals have been ducking until now, starting from the ones raised by General Atlantic Partners.

Flipkart also has to fight off aggressive competition from the likes of Infibeam.com, Homeshop18.com (owned by Network 18, Forbes India’s publisher), Snapdeal.com and Indiaplaza.com. In books, for instance, Flipkart has over the last few months started raising prices across the board.

Which is why, it will be interesting to watch how the hypothesis that puts serving customers over everything else holds up. On the other hand, Flipkart’s competitors too cannot endlessly burn the same fuel it does, venture money, to buy market share.

“If consumers buy only for cheaper prices, free delivery, free returns and free CoD… then the question is, will anyone ever make money? I don’t think anyone has a good answer to that,” says Kanwal Singh of Helion Partners.

Flipkart is also moving fast to launch apparels and has hired senior people to spearhead the effort. This category is crucial for Flipkart because at 30-40 percent, it has much higher gross margins than books (where discounting has wiped most margins to single digits) or electronics (6-8 percent). Ironically, the current market leader in apparel is Myntra, which has Accel and Tiger Global as investors.

Finally, there are the ‘softer’ issues around culture. After stymieing the first set of professionals who joined in 2010, Flipkart has gone back and hired a second set of people, in most cases even more experienced and senior than their earlier hires.

These include Karandeep Singh, earlier a vice-president at Sapient India, as CFO Ravi Vora from Heinz India as head of marketing and Aparna Ballakur, who formerly headed human resources at Yahoo! India.

Singh is now implementing Oracle Financials, the first major enterprise software Flipkart has chosen not to code from scratch. Why now? “This is a big investment and we had to reach a stage where it could be justified,” says Binny.

Meanwhile Ballakur will need to walk the fine line between bringing in a more professional and open work culture while retaining the good aspects from the old. Why did Flipkart wait so long? “We’ve been looking since 2009, but just didn’t find the right person,” says Sachin.

“It’s typically an investor who puts pressure on start-ups to professionalise or scale. It’s a tough transition,” says Priya Chetty-Rajagopal, of global executive recruitment firm Stanton Chase.

What the Bansals need to add now is humility and, perhaps, dilute their audacity and ballsy ways to stay afloat.

(Additional reporting by Shishir Prasad & Pravin Palande)

First Published: Jul 06, 2012, 06:52

Subscribe Now