The new corporate headquarters of the Rs 4,800-crore DS Group—a 6 lakh square feet and mostly marble office space—is swanky, glitzy and modern. Yes, it’s all that. But for Rajiv Kumar, the group’s vice chairman, and his family, the new office is also a symbol of how far they have come and where they want to go—beyond the tobacco brands that presently define them. “We want to be a conglomerate…the tobacco business is just 25 percent of our revenue today,” says Rajiv Kumar, adding that the traditional business will become even smaller in the coming years.

Undoubtedly, they have come far—philosophically, strategically and geographically. From a small corner shop in Delhi’s old and walled neighbourhood of Chandni Chowk to seven-star type premises in Noida, it has been quite a journey for the Kumars from purani Dilli. Their business was founded in 1929 when Lala Dharampal (the D in DS) set up a perfumery shop in Chandni Chowk, and later diversified into chewing tobacco. His son Satyapal (the S) would take the business to new heights by introducing chewing tobacco brands such as Baba and Tulsi as well as pan masala (a betel nut product) brand Rajnigandha.

Though the company began diversifying into non-tobacco businesses in 1987, the push became a drive from 2006 onwards. In the last eight years, Satyapal’s sons—Rajiv Kumar and elder son Ravinder Kumar, chairman of the DS Group—have set up seven new businesses ranging from hospitality to dairy. They are also firming up plans to invest in the power, steel and cement sectors. “The FMCG business [which includes confectionery, spices and beverages] will drive growth,” says Ritesh Kumar, Ravinder’s son and a director in the group.

The transformation impetus is understandable. According to Euromonitor’s October 2013 study on the smokeless tobacco industry, volumes have been reducing for the last two years, tanking by 26 percent in 2012. The slide came after governments of 26 states and five union territories in India banned the sale of gutka (a granular stimulant mainly containing tobacco). Euromonitor estimates that the segment will see a further decline of 76 percent in volumes from 2012 to 2017.

Inevitably, during the course of the interview with Forbes India, Rajiv repeatedly assured that DS’s tobacco brands have the best standards of quality control and are in the premium segment of the industry. Apart from an experiment “years ago” to enter the gutka segment, a foray that was discontinued, DS brands Tulsi and Baba are zarda products, containing only tobacco. Though their market shares have been increasing (the two put together make DS the second largest manufacturer behind Dhariwal Industries’s RMD Gutkha in the smokeless tobacco industry), Kumar realises that doing business in such an environment will remain difficult. As Devangshu Dutta of consulting firm Third Eyesight points out, “Anything to do with tobacco is seen as part of the sin economy.”

But what pains Rajiv more is the overhang of this “perception” on his leading brand Rajnigandha. “Gutka has damaged the perception of Rajnigandha,” he says. The pan masala, which Kumar brackets under mouth freshener, is expected to gross Rs 2,000 crore in revenue in FY2014, accounting for more than 40 percent of the company’s revenue. But its soaring sales aren’t indicative of an altered image with most mistaking it for a tobacco-based product.

In this context, it is not surprising that the last four major initiatives from the DS stable have been in the FMCG segment. This, Rajiv hopes, will help achieve what, as Dutta of Third Eyesight points out, ITC has tried to do over the last few decades: Reposition itself.

![mg_75292_ds_group_280x210.jpg mg_75292_ds_group_280x210.jpg]() LESSONS FROM ITC

LESSONS FROM ITC

The first diversification for ITC (earlier known as India Tobacco Company) came way back in the 1970s when it entered the hospitality business. From 2000 onwards, ITC forayed into greeting cards, information technology, fashion retail and even agarbattis, or incense sticks. Its most successful venture has been in the foods industry. Today ITC is the largest seller of branded foods in India with a turnover of Rs 4,600 crore in FY2013. “ITC also struggled… while not all its ventures have been equally successful, the company has been able to scale up its FMCG business,” says Dutta.

Interestingly, its tobacco business is still the biggest generator of cash, that too by a large margin. ITC earned Rs 27,136 crore from its cigarettes business, working out to 56 percent of its top line it also contributes 82 percent to profit with Rs 8,694 crore. This has made it even tougher for the giant to entirely overturn its “tobacco” perception but people now know the company as much for its cigarette business as for its hotel and FMCG operations. And investors typically like the company stock with its market capitalisation at Rs 2,74,132 crore as on April 4, 2014, the highest among its peers and driven by the best-in-industry operating profit margin and return on equity.

The success of the Rs 45,000-crore ITC’s diversification is rooted in “a great lineage of professionally run management and an efficient structure,” says Dutta. “The company could leverage on these strengths to launch businesses.” Does the DS Group have the organisational strength and manpower bandwidth to persist with these efforts over the next few decades?

It helps that the family is not completely new to diversification. Its first non-tobacco venture was set up 27 years ago with the launch of Catch, packaged free-flowing salt and pepper. The brand was later expanded to include silver foil and bottled spring water. Leveraging on its strength in developing fragrances, the family launched PASS PASS, a now popular mouth freshener.

Similar to ITC, the Kumar brothers increased their diversification drive from 2000, launching hospitality projects, packaging, agro forestry and latex rubber thread businesses. Meanwhile, Catch made its entry into the spices and beverage segments. In 2011, the brothers bought a dairy unit in Rajasthan, including an institutional brand called Dairy Max. Expanding the FMCG basket, they entered the confectionery business with Chingles chewing gum last year.

To the family’s credit, a few of these brands have gained scale and are profitable. Catch grossed Rs 350 crore in FY2013 and is considered the second-largest in the North Indian spice market after MDH. The mouth freshener brand PASS PASS broke even after seven years. “We are not in a hurry. We understand that it takes time to create a brand,” says Rohan Kumar, Rajiv Kumar’s son and vice president, business development. His father adds that the family took seven years to master the hospitality business through its first property in Nainital. “We now have a resort in Jim Corbett National Park and have four upcoming projects in Jaipur, Guwahati, and Kolkata,” says Rajiv.

This success sets the Kumar family apart from their peers in the tobacco business, including the Dhariwals, who own RMD Gutkha. Though RM Dhariwal—chairman of Manikchand Group—also diversified into mouth fresheners, bottled water and flexible packaging, his line-up doesn’t include prominent brands such as Catch or PASS PASS.

The Kumars (now in their fourth generation) have also succeeded in keeping their flock together, unlike the Kotharis of Kanpur, who own the Pan Parag pan masala brand. The family split in 1999 divided the pan masala and writing pen businesses between the two sons of patriarch MM Kothari. It should be noted that Pan Parag is no longer the biggest business for the family. More than half of the BSE-listed Kothari Products’s 2013 revenue of Rs 5,043 crore came from international trading.

LOOKING AHEAD

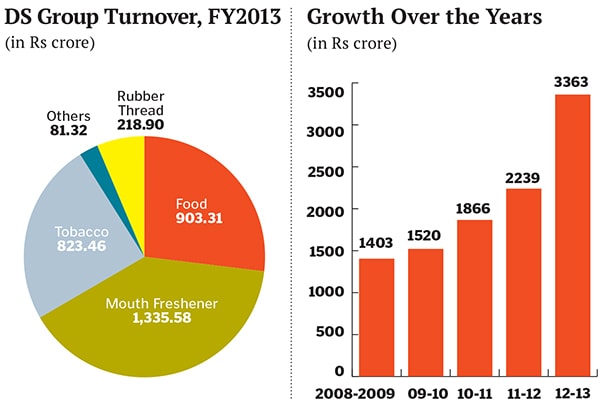

Financially, DS has had a good run since 2010, growing from Rs 1,400 crore to Rs 3,362 crore in 2013, and net profits of Rs 291 crore. It expects to gross Rs 4,800 crore in FY2014. Personally, though, the family is more enthused by the success of its FMCG brands Catch and PASS PASS. “We want to be No. 1 not in numbers but in quality,” says Rajiv.

His strategy is two-pronged in the coming years. One is to keep up the marketing blitz on Rajnigandha to improve its brand positioning. Extending the brand’s spread, Kumar launched Rajnigandha Pearls last year, a cardamom-based mouth freshener and roped in Bollywood star Priyanka Chopra as its brand ambassador. Like earlier campaigns, the latest one is also handled by McCann Worldgroup India. Its India head and creative director Prasoon Joshi says that Rajnigandha is a “cultural product” that needs to evolve and become contemporary and aspirational as times change. “Pan and betel nuts are steeped in Indian culture. So is hair oil but it needed to evolve with competition from shampoo,” says Joshi.

The second part of the strategy is to push the FMCG business. And that is where the real challenge for Kumar lies as he diversifies into other segments, says Arvind Singhal, chairman of consultancy firm Technopak. “The customer doesn’t care about perception [of the tobacco legacy]…but as it enters new businesses, does it have the bandwidth to create a new marketing strategy, new distribution and new branding? Even if everything comes under the FMCG umbrella, products are fundamentally different. For instance, SUVs and two-wheelers are from the auto industry. But they are not the same… it takes a long time to make the transition,” says Singhal.

Currently, Kumar’s biggest investment, for instance, is in dairy. After spending Rs 50 crore in modernising and expanding the unit in Rajasthan, Kumar has earmarked another Rs 150 crore to develop the business. Apart from institutional brand Dairy Max, a retail cousin, Ksheer, was recently introduced. “Right now we are focusing on the Rajasthan market [where the unit is located],” says Anshu Dewan, head of the dairy business. With a product basket that covers the whole dairy range, including paneer (cottage cheese), yoghurt and flavoured milk, the plan is to take the brand across the country. But in Rajasthan itself the new brand faces tough competition in the form of government-owned Saras.

The scenario will be similar in every other FMCG segment too, where well-entrenched players hold on to their turf closely.

But Rajiv is up for the challenge. He says he recalled stocks of Chingles a couple of months after it was introduced in the market when a colleague said the chewing gum might have a “stickiness” problem.

“I had to do it to ensure that the brand is accepted,” he says. The chewing gum market in India is growing at a healthy 25 percent every year with players like Perfetti and Wrigley’s dominating.

The competitive landscape might be even tougher in other categories, especially in the food and beverage ones—a natural progress from here. Aware of that, Rajiv is expanding the organisation’s width of operations DS’s retail reach has increased from 5.5 lakh outlets in 2010 to 8.5 lakh in 2013. In the mouth freshener business alone, says the business head CK Sharma, the sales force has grown from 2,070 in 2010 to 3,780 in 2013. The top team is also trying to increase know-how, including getting the marketing strategy right with help from Tata Strategic Management Group.

But it is also the rustic wisdom that has been passed down through the generations that will hold the family in good stead. And they have even institutionalised some of that inherent knowledge by creating an in-house design studio department. This, of course, will be housed in the new corporate headquarters. The symbolism continues.

LESSONS FROM ITC

LESSONS FROM ITC