Bajaj Auto: Long ride home

It's the world's third largest motorcycle company, but what will it take for Rajiv Bajaj to make it India's largest?

Image: Nayan Shah for Forbes India August 2017. The room in Pravasi Bhartiya Kendra in New Delhi was packed to the rafters with political heavyweights, helmed by Prime Minister (PM) Narendra Modi and his entire cabinet, Niti Aayog CEO Amitabh Kant and over 300 business leaders from different industrial sectors. The head honchos were called in for a two-day brainstorming on the Make in India programme as a part of a government initiative called ‘Champions of Change’.The industrialists were divided into six to eight groups of 50 to 60 and, at the end of the second day, one from each group had to make a 10-minute presentation to the PM. Rajiv Bajaj, managing director of motorcycle maker Bajaj Auto, who led one group, chose to outline five initiatives to take the programme forward.

Image: Nayan Shah for Forbes India August 2017. The room in Pravasi Bhartiya Kendra in New Delhi was packed to the rafters with political heavyweights, helmed by Prime Minister (PM) Narendra Modi and his entire cabinet, Niti Aayog CEO Amitabh Kant and over 300 business leaders from different industrial sectors. The head honchos were called in for a two-day brainstorming on the Make in India programme as a part of a government initiative called ‘Champions of Change’.The industrialists were divided into six to eight groups of 50 to 60 and, at the end of the second day, one from each group had to make a 10-minute presentation to the PM. Rajiv Bajaj, managing director of motorcycle maker Bajaj Auto, who led one group, chose to outline five initiatives to take the programme forward.

Make in India has, of course, been the government’s effort to attract investments from across the globe to spur manufacturing in India. “Go and sell in any country of the world, but manufacture here,” Modi had declared when he launched the programme in his maiden Independence Day speech in 2014.

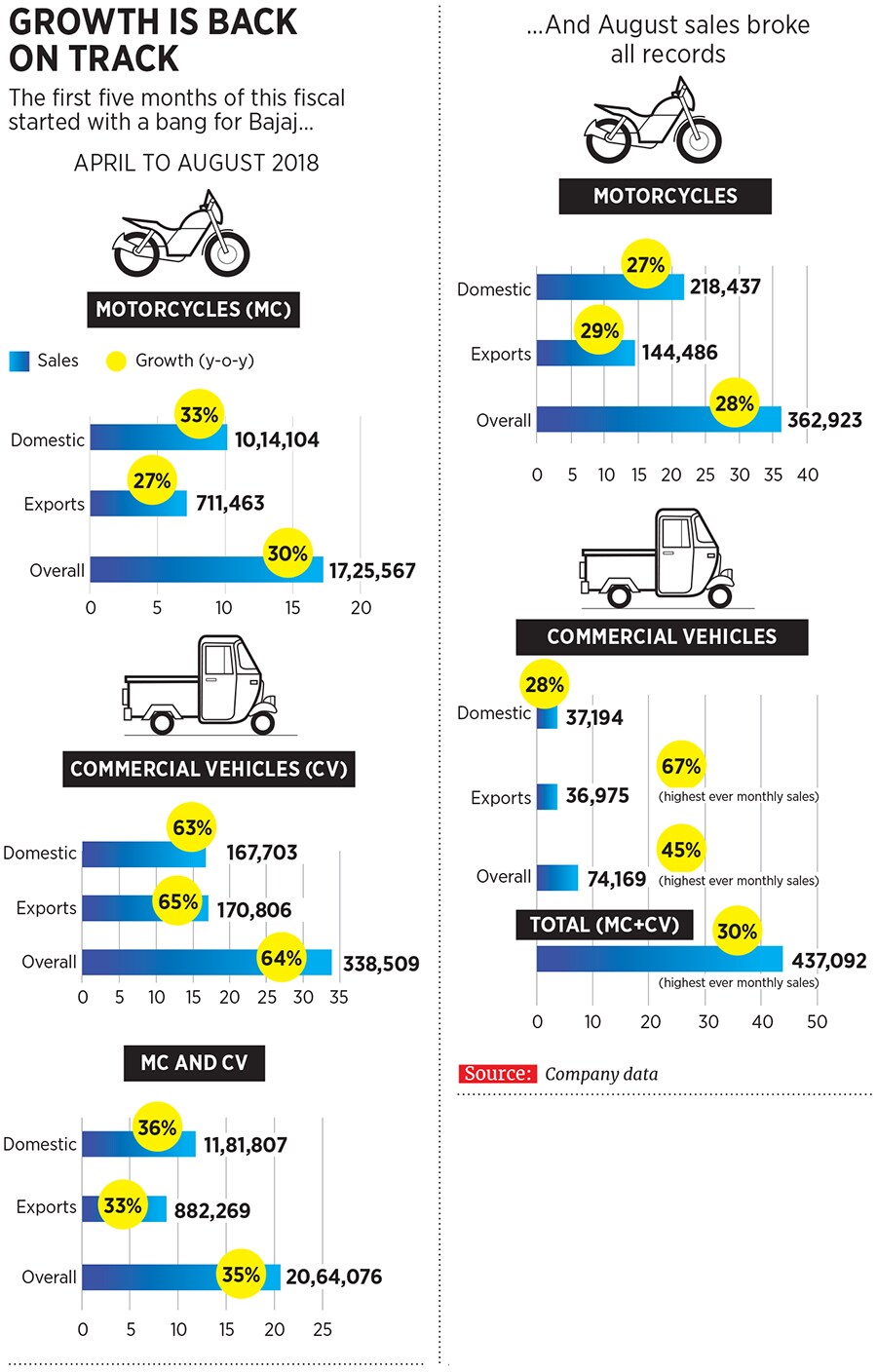

Bajaj knows a thing or two about making in India and selling to the world. He’s been doing that for more than a decade now. As of the first five months of fiscal year 2018 (April to August), over 40 percent of Bajaj’s two- and three-wheeler production—some 0.71 million and 0.17 million, respectively—were sold in more than 70 countries. That’s enough to make Bajaj Auto the third largest motorcycle maker in the world.

The third-generation entrepreneur—his grandfather Jamnalal Bajaj founded the company in the 1940s—likes to point out that Bajaj Auto may be 73 years old but, as a motorcycle company, it is still a teenager the indigenously-developed Pulsar—Bajaj’s first success in motorcycles, on its own—was launched in 2001. “We’ve gone from being a newcomer 17 years back to World No 3, which means we are ahead of the Yahamas, Suzukis, Kawasakis, and all European, Chinese and American (motorcycle) makers.”

But here’s the paradox. Bajaj Auto may be No 3 in the world, but in India it is still a distant No 2 in motorcycles—and a dismal No 4 in two-wheelers, if you include scooters. Bajaj is pretty clear that scooters are not a focus area, and that he cannot be bracketed with those who make them. “Why should we leave gaps in the motorcycle portfolio and think about scooters?” he asks.To be sure, the gap with the leader, Hero MotoCorp in India, in motorcycles, is huge. “Unfortunately, India is the market where for a long time we have not been No 1,” concedes Bajaj. Hero MotoCorp had over half of the motorcycle market in the bag as of August, with Bajaj Auto at a distant 18 percent. The biggest reason for this variance is the Pune-headquartered company’s inability to make a dent in the segment that matters most: The commuter or executive or value-for-money segment, where Hero MotoCorp rules the roost, selling some 587,000 units in August—primarily Splendor, HF Deluxe Passion and Glamour Bajaj Auto’s August sales in this segment were a paltry 138,582 units.

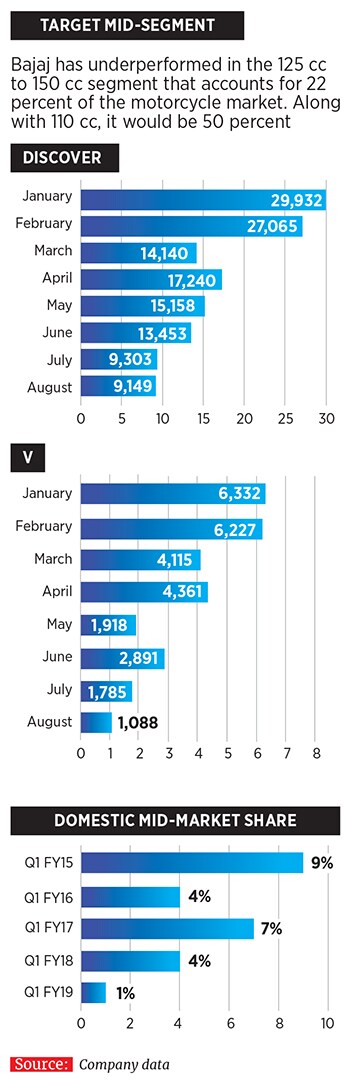

For over a decade now, Bajaj Auto has been trying to gain share from Hero MotoCorp. With little success. The Discover 125, the first entrant into 125 cc, promised much—with peak monthly sales of 60,000 in FY12-13—but the decision to extend it into 100 cc territory proved disastrous. Discover sales as of August were down to a paltry 9,000.

Another worry for Bajaj is V, which was launched with much fanfare, but is going the Discover way from 6,332 units in January this year to 1,088 units now. The failures of Discover and V in the mid-segment of the motorcycle market have left Bajaj vulnerable.

Market share has fallen from a high of 9 percent in the first quarter of fiscal 2015 to a paltry 1 percent in the first quarter of the present fiscal. Bajaj is candid about the gap in the 125 cc segment. “We are missing out on this (segment), which I think is about 2.5 lakh bikes a month. (But) we are not vacating the 125 segment. We are working on a new product and will cover it up,” he points out. “This is the right time to do it and we have stepped on the gas.”

It is the right time because, other than the mid-segment, Bajaj Auto is firing on all cylinders on other fronts. While domestic sales of motorcycles in August clocked 218,437 units, a jump of 27 percent over a year ago, exports of two-wheelers leapfrogged by 29 percent to 144,486 units. Exports are significant because of the fatter margins—20-30 percent on bikes vis-à-vis 10-15 percent on domestic sales, reckon auto analysts. They’re also crucial because the growth comes after two consecutive years of decline the fall in fiscal year 2017 was 16.5 percent.

What all this also means is that India’s fourth biggest two-wheeler maker has reclaimed its throne of the second biggest motorcycle maker from arch rival Honda. While Bajaj Auto sold 10,14,104 motorcycles in the first five months of this fiscal, Honda managed 942,642 units between April and August. Bajaj Auto is slightly ahead of the Japanese rival in share with 16.9 percent as against Honda’s 15.7 percent Honda (overall, in two-wheelers, though, Honda’s share is 28 percent). The gap widened by a few points in August alone: 18.1 percent against 16.7 percent.

One reason for the spurt in growth in motorcycles is the cut in prices in the entry-level product, the CT100, by ₹3,000, a 20 percent drop from the earlier price. From 36,601 units in March, sales more than doubled to 82,424 units in August.Kevin D’Sa, president (finance) of Bajaj Auto, defends the aggressive strategy of gaining volume market share at the cost of margins. “It’s important for the company to get a share of 20-25 percent in the domestic market. Then only I can be a true global player,” he says, explaining why analysts shouldn’t read too much in a 2 percentage point drop in Ebitda margins to 18 percent. “The rest of the business will more than compensate for what we lose for the moment,” adds Bajaj.

Bajaj Auto’s other entry-level bike, the Platina 100, has also seen a jump in numbers: From 34,758 units in March to 45,921 units in August. At the sporty end, the company added two new variants to the blockbuster warhorse, the Pulsar. These helped boost sales of the Pulsar family—ranging from 150 cc to 220 cc—from 53,490 units in March to 70,051 in August. KTM and Avenger help Bajaj Auto dominate the top end of the market. Bajaj is now planning to expand its premium play in the 400-plus cc range with the Husqvarna—being developed with KTM—and an alliance with British bike maker Triumph is being finalised.

Bajaj believes customers are willing to change once they see a 20 percent advantage. In the CT100’s case, it’s 20 percent less on price. On other fronts—space, power, comfort and mileage—it’s 20 percent more. He’s now planning to use the 20 percent formula on the Platina, by offering “20 percent more” for the same price: Same money, more bike. The “more bike” will be courtesy of a “low-cost innovation”, which company officials are keeping close to their chest.

Meantime, in three-wheelers—a niche business where globally the next competitor is Piaggio—Bajaj is a comfortable No 1. Margins, too, are attractive here, at 30-35 percent, according to auto analysts. And, as Bajaj says, the quadricycle, branded Qute, has been developed to defend the three-wheeler niche. The Qute is finally being rolled out after battling a string of public interest litigations in courts for the past six years.

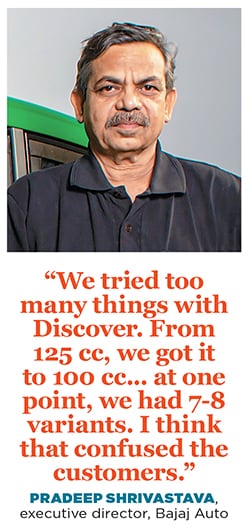

All’s well on the exports front, at the entry level, at the top end—except on the front that matters most at home, the mid-market. “I don’t think we can do much with it (Discover) in the domestic market,” acknowledges Bajaj. Once a brand, he lets on, falls out of favour with the consumers, there is no point pushing it. The failure, though, he insists has got nothing to do with its quality. “The fall of Discover is due to dilution in the positioning,” he says. Though Discover was the country’s first 125 cc motorcycle, the company later introduced a 100 cc version. That’s when the problem started.

The logic of having a 100 cc was simple: The sales team reckoned that communicating 125 cc values would help push up the 100 cc cousin’s numbers. The ploy didn’t work.

Pradeep Shrivastava, executive director at Bajaj Auto, in charge of manufacturing, labour procurement and quality, and a core member of the team over the past 17 years—along with D’sa and chief technology officer Abraham Joseph—attributes the Discover debacle to too much experimentation. “We tried too many things with Discover and changed the variants very quickly,” says Shrivastava, adding that at one point, Bajaj Auto had over seven variants of Discover. “I think that confused the customers,” he says.Bajaj is more candid. “In pursuit of numbers, we lost the positioning,” he rues. When Merc makes an A class, it doesn’t advertise it, the communication is always about the E class or the SUV. “The positioning is best or nothing.” The Discover learning will stand the company in good stead with its other models—the Pulsar won’t be taken down into the 125 cc segment and the Platina (100 cc) won’t go up into that territory. “We would be making a Discover mistake if we do so,” says Bajaj. But if Bajaj Auto is planning to address its chink, the mid-market, which Hero MotoCorp has a stranglehold on, the leader is eyeing territory that belongs to Bajaj Auto—the sporty, high end segment. This September, Hero MotoCorp launched the Xtreme 200R, its first 200 cc bike.Pawan Munjal, chairman and managing director of Hero MotoCorp, is upbeat on the prospects of striking it big in the premium segment. “For us, the Xtreme 200R is not just any other product launch. It will catapult us to where we have been earlier in the premium segment,” he says, adding that it will help Hero consolidate its market leadership. “We will soon commence sales of the Xtreme 200R in our global markets.” The company is planning another product in the premium segment: XPulse 200. “While Hero continues to be an unrivalled leader in the domestic motorcycle segment with an over 50 percent share, it’s now focusing on the premium segment,” asserts Sanjay Bhan, head of sales, customer care and parts business at Hero Moto.

Suggestions of Hero playing the price card at the high end—just as Bajaj has at the entry level—evoke a smirk from Bajaj. For two reasons: In the 100 cc segment, it is a two-horse race between Hero and Bajaj Auto, who have 90 percent of the segment with them, says Bajaj in the Pulsar segment, though, while Bajaj Auto is sitting pretty with 40 percent, Honda, TVS, Yamaha and Hero Moto are at the rear. “This whole idea amuses me. You are telling me this fellow who is last in this segment will launch a price war? A price war can happen if TVS or Honda do something, but not Hero. Hyundai can launch a price war against Maruti, but Tata can’t.”The battle at the top end, however, will still be smaller than the one for the segment that counts the most—the value-for-money mid-market: Where consumers look for an attractive price, mileage, quality, low maintenance and high resale value. Hero Moto has cracked that game. Bajaj Auto could wait for the market to evolve, with a majority of buyers preferring design, style, power and features over mileage and price. But Bajaj knows that won’t happen. Not in a hurry. The choices to crack the market that lies below the Pulsar are clear: Give the same (product for) less. And give more (features) for the same price.

Epilogue

On September 7, Bajaj Auto participated in a Niti Aayog-organised global mobility summit at Vigyan Bhawan in Delhi where it showcased its electric three-wheeler to the PM. The PM was suitably impressed, Bajaj Auto officials told Forbes India.

What’s keeping the core team at Bajaj Auto busy—besides taking on Hero MotoCorp—is urban mobility. “When we develop electric two-wheelers, whether bikes or scooters or mopeds or bicycles, it will be a Tesla-like business. This brand, whatever it will be called, should ideally be purely electric,” says Bajaj. The best solution, he avers, is when the brand itself is electric. “Toyota is not an electric brand. It’s a petrol, diesel brand also making electric vehicles. But with Tesla, it’s not the case. You would be aghast if tomorrow Tesla launches a petrol Tesla. This urban mobility from us would be very disruptive,” adds Bajaj.

He’s launching new variants of motorcycles, new brands, even a new product, but Bajaj knows that the technology that goes into all of these is the same. Urban mobility is another ballgame. “It’s completely new and a big learning. We will take small steps. First we have to be aspirational, (the products will) be expensive, will not sell millions but this is not something a company can miss out on. Nothing may happen for 10 years, but when it does, you would be left out. One has to start early.”

Fixing the past, growing in the present, and beginning work on the future are all a work in progress for Rajiv Bajaj. As the wise man said: “The future depends on what you do today.”

First Published: Sep 18, 2018, 11:42

Subscribe Now