Xiaomi: In-store and in India

Xiaomi, a Chinese smartphone comet online, had to broaden its retail base. Manu Jain is helping to pull that off

Manu Jain, head of Xiaomi India, takes a selfie with his colleagues

Manu Jain, head of Xiaomi India, takes a selfie with his colleagues

Image: Namas Bhojani for Forbes

Chinese phone maker Xiaomi started off its pre-Diwali sale in India in 2017 on a high note—selling 1 million phones in 48 hours in September. It was a reminder of how potent the online marketing channel can still be for a company that lit up its home market that way three years ago.

But the company’s lustre had faded in the meantime. The bigger story for Xiaomi in 2017 is how it is using bricks and mortar to regain momentum. And India, its second big market, is in the forefront of that effort.

For the first half of 2017, Xiaomi was the first runner-up in the country’s smartphone segment, after Korea’s Samsung.

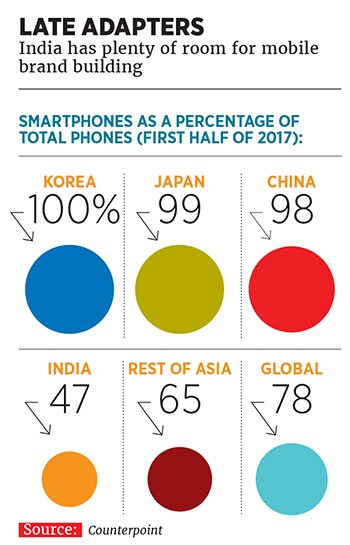

Globally, this matters: India has the second-largest smartphone base after China but still has only 300 million users against China’s 710 million. Although China remains a key battleground, its market is getting saturated. Hence, ever more competitive Chinese brands are assiduously wooing Indian consumers. In that first half of 2017, they combined for a 54 percent share.

“We’ve been able to bring really high-end, high-quality products and make them affordable,” says Manu Kumar Jain, 36, who heads Xiaomi India and is a global vice president. “Phones with similar specs—for the price ranges that we offer—will cost double with a competitor.”

Xiaomi, which entered India in 2014, is looking for revenues there to exceed $2 billion for 2017—doubling from last year. (Margins are wafer-thin, but the Indian subsidiary has been profitable since 2015.) Overall sales should pass $16 billion. Xiaomi founder Lei Jun

Xiaomi founder Lei Jun

Image: Aly Song / Reuters

Jain’s operation has running room—India’s $19 billion market (wholesale smartphone revenues) is expected to cross $30 billion by 2020. Closely held Xiaomi may still sell three times as many phones in China, but India is its best hope for gains that might at last unlock its IPO opportunity.

Yes, Xiaomi can work the online channel better than anyone—it has half of such sales in India. But key to Jain’s push are the physical contact points: “Preferred” retail outlets (which give Xiaomi a push over rivals they sell) and “Mi Homes” (experience/sales centres). “Xiaomi has managed to create a lot of buzz around the brand,” says Navkendar Singh, senior analyst at global advisory firm International Data Corporation’s (IDC) India office. “They have good customer engagement. And they also refresh their portfolio pretty frequently.”

Xiaomi is churning out one phone per second at its two manufacturing facilities in Andhra Pradesh (in partnership with Foxconn) to cater to Indians. It has already invested $500 million in India (along with its various partners) and is looking to pour in another $500 million over the next two years, creating an estimated 20,000 jobs along the way.Started in 2010, Xiaomi took China by storm with its $100 to $300 phones. Online selling cut costs and reached customers directly. Revenues doubled for a few years, and founder Lei Jun was named Forbes Asia’s 2014 Businessman of the Year.

But in 2016 shipments fell by 36 percent amid fierce competition from Chinese rivals Huawei and Oppo. Lei’s estimated net worth, too, was cut in half from a high of $13.4 billion in 2015.

Cue the offline reboot. Xiaomi had come to India with its online prowess but found that 70 percent of the market was in stores. So over the next two years it set up 600 service centres, stitched up partnerships with 650 retailers and opened seven Mi Home centres. It recently tied up with Kishore Biyani’s Future Retail to sell its two most successful models at Big Bazaar outlets during the festive season.

In China, Xiaomi now has 200 stores and is looking to add 800 by 2020. Already, this is showing results: Offline sales in China grew significantly in 2017, and in the second quarter, Xiaomi overtook Apple as the fourth-largest phone shipper in China. Worldwide, it ranked fifth in the second quarter, with a 59 percent rise, a considerably faster climb than the rest of the top five.India is setting the pace. “We expect to be the number one smartphone brand soon,” says Jain, who has an engineering degree from IIT-Delhi plus a postgraduate diploma from the premier Indian Institute of Management in Kolkata.

He worked as a consultant with McKinsey out of college and then co-founded fashion retailer Jabong.com in 2012 with a group of friends. He quit the Delhi startup in early 2014. (Jabong was sold to Flipkart in 2016. Jain offloaded his stake for an undisclosed sum.)

Back in Bengaluru and previously acquainted with Xiaomi’s co-founder Bin Lin through a common friend, Jain soon joined the phone maker. For a while he was the only employee in India. “I’d be opening the door, serving tea and coffee myself and also discussing deals worth hundreds of crores,” recalls Jain. The India staff now exceeds 300.

But the initial days were tough. For instance, during Diwali 2014, there were rumours that the Indian Air Force had banned Xiaomi phones and sales dipped. (Official tensions with China are always in the background.) Then came a copyright case—regarding chipsets—slapped by phone maker Ericsson. Some products also backfired, like the tablet Mipad, which was later withdrawn from the market.At that time, Jain worked closely with the charismatic Hugo Barra, who used to head international sales for Xiaomi and has since moved to Facebook. These days, Jain connects with Xiaomi founder Lei Jun to craft strategy. Jun doesn’t speak much English and Jain doesn’t know Mandarin, but the two catch up many times a day to chat, using in-house translators or even Google Translate. Jun visits India at least once every quarter. Jain, who has an undisclosed equity stake, hosted him at his Bengaluru home recently. (Bin Lin, meanwhile, continues to oversee the entire company’s growth.)

By 2016, Xioami rose to the No 5 position in a bunched Indian smartphone ranking after Samsung. Starting this year things looked even better, spurred by the government’s demonetisation move to formalise transactions, which boosted online buying. Also helpful was its $150 to $200 Redmi Note 4 series. With an all-metal body, fingerprint scanner and 13-megapixel camera, it became India’s favourite model for the first half of the year, selling nearly 5 million phones, as per company data.

Xiaomi appeals, in part, to young adults upgrading from a $100 to a $200 smartphone. This is a notch above where domestic outfits like one-time star Micromax had gotten a foothold. “Micromax and other India-based vendors were dominant in the sub-$100 category,” says IDC’s Singh. “But with the huge onslaught of Chinese vendors in the $100 to $250 category, the sub-$100 lost its appeal, since there were better-designed devices with high specifications.”

In this sector, Oppo and a similarly aimed Chinese brand, Vivo, are on a marketing blitzkrieg, splashing their names across billboards and mom-and-pop shops. They are wooing cricket-loving Indians by sponsoring major cricketing events. And they are luring dealers with good markups.

Xiaomi’s answer is to use social media and Mi fan clubs to spread the word. It’s online Mi Community has more than 2 million Indian users. Clubs bring together Xiaomi fans, who discuss everything from headphones to screens to battery capacities. They also beta test the phones under extreme conditions—like watching movies for 48 hours straight or playing videogames for 20 hours at a stretch.

Jain points out that the phone itself is not the endgame. “Our smartphones will be at the centre of a universe of products,” he says. Xiaomi fare in China includes such products as shoes, air purifiers and TVs. It has invested in 89 hardware startups. In India it has already rolled out power banks, audio accessories and fitness bands.

Xiaomi also has its own operating system (MIUI) and an internet platform, Mi.com. (MI stands for “Mobile internet”, and Xiaomi—which means “millet” in Mandarin—was named to signify ubiquity.)

“The momentum is there, but their profitability is limited by [Xiaomi’s] business model,” says Neil Shah of Mumbai’s Counterpoint Research. “Since this is a volume game, global-level scale will be important and thus growth beyond the India or China markets.”

That’s true for the Chinese rivals, too. “They have started expanding their presence in Southeast Asian countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam,” says Xiaohan Tay, research manager for client devices at IDC. “These are price-sensitive markets, and vendors have to continue to focus on pushing their low-end and mid-range products in these emerging markets.”

Jain is conscious of the hypercompetition around him. He says his backpack has at least 20 new marketplace releases at any given time. His desk drawers are jammed with cellphones of varying colours, screen sizes and specs. But while he had cited the market title as an expectation, “We don’t chase the No 1 ranking,” Jain professes. “Our philosophy is to focus on the inputs—as in the right product, the right innovation, the right services and the right business model. The output, which is the market share and rankings, will automatically happen.”

(Additional reporting by Jane Ho)

First Published: Dec 18, 2017, 07:38

Subscribe Now