Why Mahindra & Mahindra Needs Reva

With a majority stake in Reva Electric Car Company, M&M now gets a better chance to join the global race to develop an electric car

Anand Mahindra recalls bumping into an enthusiastic private equity investor at the World Economic Forum in Davos earlier this year. The moneyman had just made an investment in electric vehicle evangelist Shai Agassi’s firm Better Place — and couldn’t stop talking about it. Better Place was on track for a full commercial rollout next year in Israel. Agassi had developed an electric car branded as Zoe, in partnership with Renault and had also built a whole new infrastructure of charging points all over the country. As he heard the investor wax eloquent about Better Place, the 55-year old vice chairman and managing director of the Mahindra & Mahindra group couldn’t suppress a smile. More than 10 years ago, he too had dreamt up a similar concept of employing a cassette-like, battery hire EV operation in New Delhi.

At that stage, M&M was largely a jeep and tractor-maker, with ambitions to move into personal vehicles. Yet it had begun taking bets in the new and untested field of electric vehicles, even though it remained a weak alternative to the internal combustion engine technology. “We had submitted an ambitious plan to the government to decongest Connaught Circus, one of the busiest and most-polluted areas in the capital,” recalls Mahindra. The plan was simple: All two-wheeler traffic would be stopped from entering the 5 sq km area. People would be encouraged instead to use 10-seater electric vehicles that ran on a circular route. Bijlee, M&M’s EV avatar, would be powered, thanks to a chain of battery stations around the locality. The owners of these stations would lease out batteries to the vehicle operators for a modest rent. The innovative plan was nixed by Bijlee’s own mechanical problems and stiff opposition from the taximen’s union. In Mahindra’s mind though, it sowed the seeds of a whole new way of making electric vehicles a reality in India.

Over the next decade, as the Mahindra group expanded into sports and personal cars, the vice chairman kept his eyes on the developments in the cleantech space. M&M began working on electric versions of mainstream vehicles like the mini-truck Maxximo, as well as continuing research on hybrid technology. In September 2008, it got a wake-up call when Tata Motors, its arch rival, announced that it had bought Miljo-Grenland, a Norwegian company which made electrical vehicles. Tata also hired Clive Hickman, a veteran, to head its engineering effort behind the EV programme. It had an electric version of the Indica set for launch in 2010. By then, Pawan Goenka, M&M’s pragmatic president for the automotive and farm equipment sector, knew that they didn’t quite have the wherewithal to either play catch up or pull off an EV on their own. They needed to find a technology partner to pull together their EV strategy.

Back in Bangalore, Chetan Maini knew he was in a spot of bother. The 39-year-old technocrat and the creator of the Reva, the country’s first electric vehicle, had unveiled two brand new prototypes at the Frankfurt Motor Show in September last year. His two new models — a quantum improvement over the original Reva — had received critical acclaim for the robustness of their EV technology. Maini had used his chutzpah to put in place a new $20 million manufacturing line, which he claims would have cost any other player nearly four times more. And he had a clear plan to take these vehicles to almost 24 markets around the world. There was one small hitch: He needed lots more capital to pull off his grand plan. And his family wasn’t willing to lose any more money trying to bankroll his EV dream.

Reva Maini, the matriarch of the Maini group, knew the Mahindra clan, especially Anand’s mother, who had passed away six months ago. There was a basic trust within the two families. Exact details on how the deal moved forward is unclear. At some stage, about eight months ago, the two investment bankers on both sides decided to initiate the process of acquisition. As part of the due diligence, Pawan Goenka went to see the Reva facilities at Bommasandra, on the outskirts of Bangalore. By then, Goenka had already evaluated similar projects elsewhere in the world. But the high cash burn deterred him.

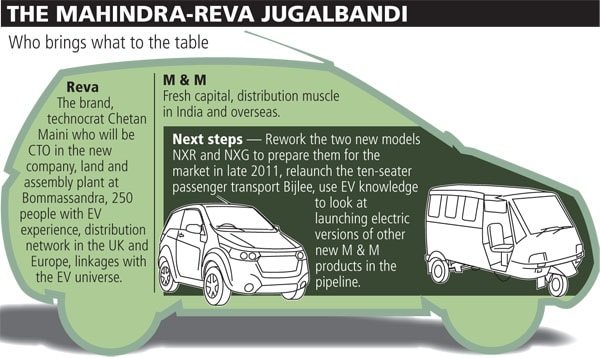

Besides, other than the EV technology, most firms did not yet have a product on the ground. Reva, on the other hand, had the experience of a product that had already done 100 million kilometres. And in Chetan Maini, they also had someone who had the global network and capabilities to drive EV technology development for M&M. Given the buzz that preceded it, M&M’s move to buy 55.2 percent stake in Reva Electric Car Company (RECC) may not have come as a surprise for auto watchers. But the significance of the move would not have been entirely lost on them either. For one, it provides ample evidence that EV technology and products is now part of the mainstream Indian auto industry. After Tata Motors, M&M is the second major auto maker to place its bets in the EV race that has already begun in right earnest around the world. To be sure, the internal combustion engine isn’t about to die in a hurry. But the fact is that tougher emission laws and greater consumer consciousness has forced every major auto maker to put in place a credible EV strategy.

For starters, turning around Reva won’t be a walk in the park for M&M though. EV technology, for most part, is still evolving and far from reaching maturity. Much of the ecosystem required for the technological development is still absent in India. For instance, in China, there wasn’t even one lithium ion battery maker 10 years ago. Today, there are 500 lithium ion battery makers, whereas in India, there still isn’t even one. Suppliers are scarce for even motors, electronics, charging systems — they are only just about to wake up to the opportunity now. Therefore, building a cost-effective supply-chain based on large-scale imports, as Maini discovered, remains a tough challenge. Finally, Goenka will also have to cut his cloth according to its size. The size of their investment in Reva will have to be carefully calibrated: Not too much for them to lose a lot of money, and yet enough to get a fast track into the EV opportunity.

As chairman of the new company Mahindra Reva Electric Vehicle, Goenka is under no illusions about the challenges ahead. “The success of the venture depends, to a large part, on how well the NXR and NXG (the two new models) sell,” he says. The Reva NXR will run on a lithium-ion battery and will have a top speed of 104 kmph and a range of 160 km on a full charge. “The Reva is arguably not a great product on the road — and we are aware of its limits,” says Goenka. “Probably that is why it is still available to us,” he adds with a touch of wry humour. M&M’s design team will work with the Reva team on the vehicles with their own knowledge of ergonomics and customer preferences, before the NXR is ready for launch by the middle of next year.

Mahindras will also use the Reva technology to redesign the Bijlee, and to enhance the electric version of the Maxximo. The vehicle currently sells in India, UK and Norway, with a smattering of sales in half-a-dozen other countries. “The plan is to use M&M’s network in Italy, South Africa, Chile and Brazil, where we think there could be a good market,” says Goenka.

M&M’s big bet is, in many ways, on Indian frugal engineering capabilities. Maini may have run short of cash to fund his big EV dream, but his reputation in the EV world was squarely built on his ability to come up with breakthrough solutions at a fraction of the cost that it took the rest of the world. “Technological value is still coming; it is very nascent to India. We were very efficient and spent the money in the right things,” says Maini.

The secrets lie inside Reva’s Bommasandra factory. Maini has put in place a low-cost assembly line to produce the car. This means the company can produce at extremely low volumes at low costs. For instance, there is no conveyor line. The shell is first fitted on wheels with tubeless tyres and rolled from one workstation to the next. The Reva plant does not need a high-cost sheet metal press shop, expensive dies or a paint shop that conventional car projects use. Its body is made of strong and coloured polymer plastic that is light and dent and scratch proof. It has to be light to compensate for the extra weight of the batteries that power the car.

Also, to make up for the huge voids in the Indian EV ecosystem, the Maini group companies supplied all the car’s components, except the battery (Exide), the motor (Kirloskar Electric), motor controllers (Curtis) and accessories (Modular Power Systems). They supplied the composite car body, all stampings, axles, brakes, suspension, wheels & hubs and a host of electrical parts, including the wiring harness, charger and integrated circuits. Meanwhile, Maini continued to pull off some neat innovations. One such piece is the energy management system used in the Reva. Activated remotely by the company, this IT-enabled system has the ability to optimise battery usage for the car owner. So, for instance, extra-battery capacity can be released for someone, if they are stranded without a charging point around.

But despite the Herculean effort, things weren’t going to plan. Losses at RECC began to mount. The underpowered Reva (with a motor peak rated at 4.5 kw), was going nowhere. The car got written about and discussed everywhere, but only about 3,500 units were sold. Global competition had leapfrogged to get performance (mostly range and speed) much closer to internal combustion powered cars.

Private equity investors Draper Fisher Jurvetson and Global Environment Fund had invested about Rs. 100 crore piecemeal since December 2006 in the venture. Most of this money, sources say, has been claimed by Reva’s suppliers who had underwritten the project since its inception. These are Reva’s sister companies from the Maini Group: Maini Precison Products, Maini Material Movers, Armes Maini and Maini Info Solutions. Maini says a portion of it also went into the new factory.

According to people known to the family, there was disquiet over the Reva’s failure to find markets in India or overseas. Chetan’s elder brother, Gautam Maini, Reva Maini’s second son and the real business brain in the group, had reservations about continuing to subsidise the Reva. He is said to have argued that Maini Precision could be vastly more profitable without the burden of supplying Reva, especially now that it had certification and successfully expanded into aero engineering components. The company supplies components for the Snecma engine that powers India’s light advanced helicopter. At a time when local sourcing requirements had been made mandatory and Indian engineering firms were staring at a huge multi-billion dollar defense opportunity, what was the logic in investing behind a project that hadn’t taken off in a decade?

However, both Sandeep, the eldest of the three brothers and Chetan were appeared keen to soldier on. They believed they had a lead in the field and were loath to squander it after so much effort. “It was challenging and difficult especially in the initial years, because we were as a family putting everything in it. It was very tight. Everything that we had as a family was going into this. Every day that we were losing was putting a strain on the entire group and especially for me personally, as I was the only company that was draining it. But we created a lot of technological value,” reveals Chetan Maini.

Eventually, faced with the prospect of higher capital costs involved in developing the two new four-seater versions and taking it to market, the family decided to look for an equity partner. (Maini insists though that his reason to sell Reva had nothing to do with any differences in the family on the way forward or on account of the rising debt burden).

M&M plans to recapitalise Reva with an investment of $10 million. That will ensure that they don’t lose any of the 250-odd people who make up the Reva team since they represent the knowledge that comes with the deal. Besides, the dozens of tie-ups that Chetan Maini has forged with the EV ecosystem globally will surely help M&M. For the past two decades, Maini has attended every single global EV conference and has a network running across new ventures, big auto firms, and large suppliers around the world. “When a (new) technology grows fast, no one knows everything. Understanding that ecosystem is very important,” says Maini.

M&M could now take a leaf out of Anand Mahindra’s solution for Connaught Place. Around the world, EV policy makers are coming around to the view that the high investment in battery charging — the lithium ion battery in the Reva NXR costs $9,000 — will ensure that the cost of an EV remains steep. “The answer is to look at particular neighbourhoods, municipalities and locations, where EVs can establish an ecosystem,” says Mahindra. Last week, the US Congress did exactly that when it introduced a new Electric Vehicle Deployment Act (EVDA), which moots the development of 15 communities across the US, where an EV ecosystem will be set up. The goal is to have 7,00,000 EVs in these communities. Individuals and communities who buy electric cars could receive tax credits. Under the Bill, electric utilities are being asked to gear up for increased use and earmark outlays for research. There is also a prize for anyone who develops a battery that could last for 500 miles. By all indications, the race as begun — and with the Reva buy, Mahindra may have clearly increased the odds in his favour.

(Read our exclusive interview with Chetan Maini)

(This story appears in the 18 June, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)