Twin-win venture: How Tarang Jain built a global automotive business

As he prepares to take Varroc Engineering public, Tarang Jain joins twin brother Anurang on the 2018 Forbes World's Billionaires List

Tarang Jain bought a one-way ticket from Mumbai to Aurangabad in 1984 and in hindsight feels it was the right decision

Image: Mexy Xavier

In August 2012, Tarang Jain had his most consequential chance at hitting the big league. Almost six years on, it’s clear he’s made the most of it.

Varroc Engineering, the company he founded in 1990, had completed the acquisition of Visteon’s global lighting business. Visteon Corp is an American global automotive electronics supplier that was spun off from Ford Motor Company in 2000. Jain, now 56, had to play a delicate balancing act. A misstep would have cost him dearly, perhaps even sunk the company.

Jain had acquired Visteon for $90.5 million (₹452 crore then). What he gained was the world’s sixth largest lighting business. Varroc now had access to a company that served the best global automakers. In addition its manufacturing footprint was entirely in low-cost manufacturing economies. “[We had] the humility to accept that we were buying into superior capability and technology,” says Jain, who set about building a durable partnership with the team in Detroit. The problems Visteon faced—like low Ebitda and lack of customer satisfaction—he realised, arose because the business had not been an area of focus for the earlier management.

In order to win Visteon’s trust, Jain ensured no Indian was sent to its facilities and the Visteon managers were given full operational control. The only direction from the top was to maintain a relentless focus on customer needs.

The Visteon deal has helped Varroc emerge as a true global automotive player with plants in India, Mexico, the Czech Republic and China. Its customers include marquee global names—Ford, Jaguar, Groupe PSA and Tesla. And its mainstay products, LED lamps and matrix lamps, have a far better margin profile than the India business, which is heavily dependent on the two-wheeler market. It has also made Jain India’s newest auto billionaire, ranked 2124 on the 2018 Forbes World’s Billionaires List, with a net worth of $1 billion.

Click here: An enduring ride: Endurance Technologies’ exhilarating journey to Rs 5,000 crore

In many ways, Jain’s journey is no different from the top tier of India’s auto component makers. They’ve globalised aggressively and expanded their footprint in both developed and developing markets. Motherson Sumi, for instance, has grown its topline by 41 percent and market cap by 62 percent a year in the last decade. Their smaller India-based counterparts too have grown rapidly and regularly added capacity every few years. The BSE Auto Index has compounded at 18.9 percent a year in the last ten years.

Varroc’s journey has been on a similar vein. Successfully digesting the Visteon acquisition was a veritable turning point in its three-decade journey. This year in all likelihood should see the company emerge as a publicly-traded entity.

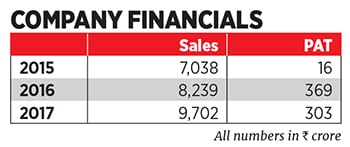

While it is hard to predict where Varroc lists, this much is certain: With sales of ₹9,700 crore in the financial year ended March 2017 and profits of ₹303 crore, it is likely to emerge in the top five after Motherson Sumi, Bosch, Bharat Forge and Exide. The group has got a 2020 sales target of ₹20,000 crore though Jain is quick to clarify that is more of a statement of intent. He concedes that he’d need another successful acquisition to get there. That won’t be a bad result for someone who in December 1984 bought a one-way train ticket from Mumbai to Aurangabad.

For Jain, who grew up in Mumbai and went to Cathedral and John Connon School and Sydenham College, starting in Aurangabad was not something he’d planned. The Jains’ relationship with the Bajaj family (mother Suman is Rahul Bajaj’s sister) helped them get a foot in the door. In 1985, the family set up Anurang Engineering, named after his twin brother (Anurang runs Endurance Technologies after an amicable business split in 2002), to supply aluminium engine casts for Bajaj scooters. A Bajaj Auto factory is located in the vicinity of the Jain brothers’ facilities in Waluj, Aurangabad.

Jain admits that the first years in Aurangabad were tough. The 22-year-old twins were trying their hand at a new business and were for the most part alone. Their father Naresh Chandra Jain who had run the Bajaj-owned Kaycee Industries was in Mumbai and only played a guiding role. In hindsight, Jain says moving to Aurangabad was the right decision. “There were so many businesses where the owners chose to stay back in Mumbai and those companies have all withered away,” he says.

Click here: An enduring ride: Endurance Technologies’ exhilarating journey to Rs 5,000 crore

After a one-year MBA from the International Institute for Management Development in Lausanne, Switzerland, Jain returned to set up Varroc in 1990 as a VAVE (value added value engineering) company. This time it was polymers that excited him. He saw the increased use of plastics and the light-weighting opportunities they brought in the future, and decided to get into this nascent area. Up north, Maruti Suzuki had started using plastics in dashboards and in time they would start using it in mirrors as well as lighting equipment.

Varroc took the help of the National Chemical Laboratory, Pune, and TIPCO—a manufacturer of plastic raw material—which had developed a glass-filled polypropylene compound, and proposed the idea to Bajaj Auto. From using it to make fans and fan covers for scooters, this has since expanded to mirrors and plastic moulds for seats and air filters. But Jain also realised that Bajaj Auto may not be able to absorb all his production. Fortunately, Videocon had set up a manufacturing unit in Aurangabad for refrigerators and became an early customer.

In the first ten years, the company had just ₹100 crore in sales and a profit margin in low single digits. Jain was conscious that his business was too dependent on one company and one product category—two-wheelers. Initially, he set about fixing the latter and in the next few years Varroc expanded its base of customers. (Despite Varroc’s current size, Bajaj still accounts for ₹1,700 crore worth of business, or half of the India business.) Today almost all two-wheeler makers in India are Varroc customers.

It was in the 2000s that Varroc found itself in a sweet spot. It grew by over 40 percent a year to ₹1,500 crore in sales in the eight years up to the Lehman crisis. Jain attributes this to a relentless focus on customer needs. Varroc set up plants where customers were—Manesar in Haryana for Hero MotoCorp (then Hero Honda) and Chennai for the likes of Royal Enfield and Yamaha. It developed its own products and paid for expensive moulds.

undefinedVarroc aims to move up to the third position, from sixth currently, in the global lighting space. [/bq]

In 2007, with cash in hand, Jain bought Imes, an Italian auto parts company that makes parts for earth-moving equipment. That was followed in 2011 with Triom, another Italian firm, which makes lighting systems for two-wheelers. And a year later came the Visteon acquisition. While Jain worked on integrating these companies, he also realised that their edge lay in their higher spends on research and development. While Visteon spent 5 percent of sales, its Indian counterparts spent no more than 1 percent, points out Jain.

Jain took a cue from Visteon and post-acquisition upped spends for his India businesses to 2 percent of sales. “Over the years the onus has also shifted on us to tell the OEMs what we can make for them. This means we need to spend a lot more in developing our own products and patents,” he says.

For now, Varroc aims to move up to the third position, from sixth currently, in the global lighting space. And while the company is always on the lookout for new opportunities, it is careful to eschew leverage. “We wouldn’t be comfortable taking more debt than our net worth,” says TR Srinivasan, group chief financial officer at Varroc. It was for the Visteon acquisition in 2012 that Varroc roped in Tata Opportunities Fund, a private equity fund, which brought in ₹300 crore for a 13.7 percent stake. “We took a contrarian call on a sector that was out of favour in 2014 and are pleased in the manner in which Varroc has executed,” says Padmanabh Sinha, managing partner, Tata Opportunities Fund.

Jain is pleased with the 20 percent growth in topline in the last decade, and the fact that the business is not disproportionately dependent on one product, customer or market. Jain says none of his product categories is likely to be impacted by the shift to electric vehicles. If anything, the move to make vehicles lighter will only accelerate. And in the lighting space there will be an increased need for and use of sensors, something the company is already working on.

Still, there are potential risks. Varroc may not be able to anticipate customer needs as rapidly changing technologies may result in competitors making parts cheaper and better. The cyclical nature of the auto industry may also result in an elongated working capital cycle during a downturn. And the company may end up spending time and effort in obtaining patents all of which may not necessarily have a commercial application.

Although the Indian two-wheeler market is growing in double-digits, globally a 3-4 percent growth in the lighting market won’t allow Varroc to reach the ₹20,000-crore target. All that Jain is willing to let on is that he is looking at a potential deal in Turkey. Meantime, Varroc last November did a small deal and acquired Team Concepts, a high-end auto accessory company. It is a category that has the potential to double to ₹5,000 crore by 2020 as Indians instal more metallic wheel rims and floor racks. Though a small buy, once again, you can’t fault Jain for not having seen the future.

First Published: Apr 12, 2018, 14:52

Subscribe Now