The swipe network: A busy digital payments landscape

Simple mobile point-of-sale machines have morphed into full-fledged payment platforms with value-added services

Mswipe machines can now be used without being plugged to a mobile phone

Mswipe machines can now be used without being plugged to a mobile phone

Image: Aditi Tailang

Recently, after buying books for his grandchildren from a shop in Shimla, President Ramnath Kovind tweeted, “Happy to experience the spreading digital payments culture in our country.”

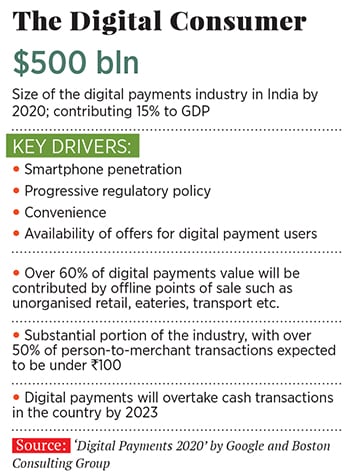

This “culture” got a big boost in November 2016 when Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared 500- and 1000-rupee notes—which made up 86 percent of the cash in circulation at the time—null and void. Upstarts like the now-ubiquitous mobile-wallet company Paytm surged in usage, going from 115 million registered users at the time of the announcement to 160 million in just 60 days.

Besides mobile wallets that dominated the market immediately after the demonetisation, the usage of Unified Payments Interface (UPI), which enable instant transfer of money from one bank account to another on a mobile platform, has also been on the rise since November 2017. According to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), 171.4 million UPI-based transactions, totalling ₹19,120 crore, were recorded in February 2018, eclipsing the 113.1 million transactions worth ₹3,650 crore clocked by prepaid instruments, including mobile wallets.

But despite the surge of mobile wallets and UPI, debit and credit card transactions still form the bulk of digital payments. RBI’s data shows that 247.1 million transactions worth ₹46,590 crore were carried out through debit and credit cards in February 2018, making up 22.5 percent of all digital transactions by volume.Traditionally, acquiring a point-of-sale (PoS) machine for processing card payments would be an expensive proposition for merchants. They would have to acquire such machines from banks with whom they already have an existing account or a relationship. (Banks, in turn, acquired these machines from manufacturers like Ingenico and Verifone, global incumbents in the space.) Each machine would have a fixed cost (around ₹13,000) as well as monthly rentals of ₹500-600. Additionally, there would be an RBI-mandated merchant discount rate (MDR), which a merchant is charged for processing card transactions (it’s 0.75-1 percent and 2-2.5 percent per transaction on debit and credit cards, respectively).

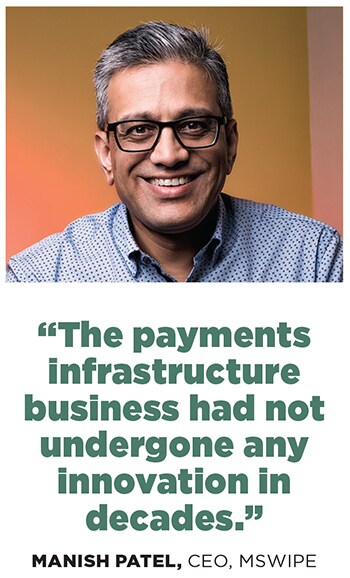

With his back to the wall, Patel decided to do some research and found that while there were about 350 million debit and credit cards in circulation in the country [in 2011], there were only about 700,000 PoS terminals [mostly across 10 cities]. Sniffing an opportunity, he put together an engineering team to build the card payment solution he had wanted as an entrepreneur, and incorporated Mswipe, one of India’s first mobile PoS (mPoS) companies, in 2013.

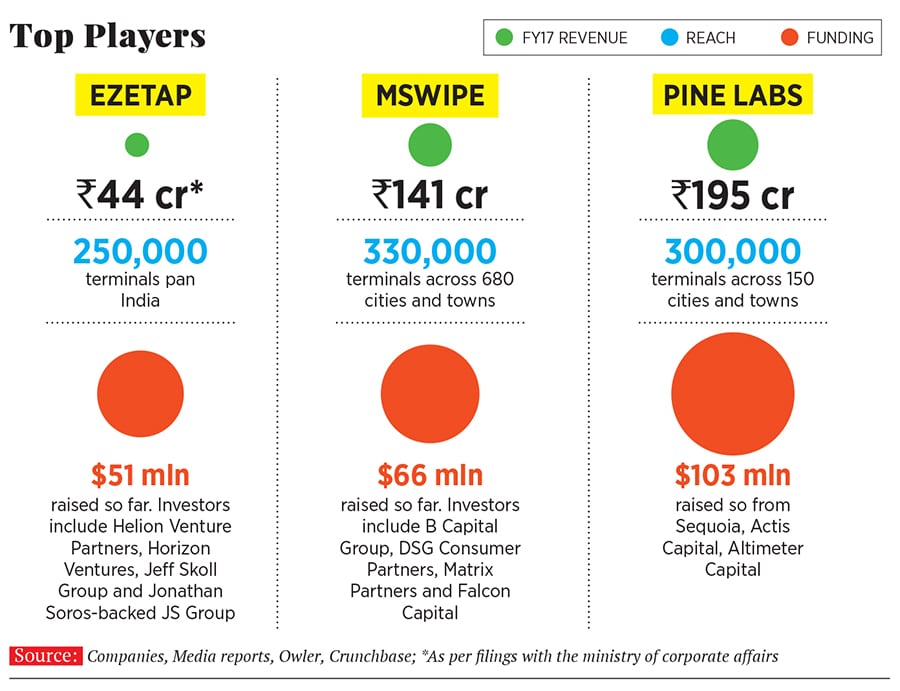

When Mswipe launched, there were barely a few payments platforms in the country Pine Labs of Noida, and Ezetap, based in Bengaluru, were among the few players. Today, several companies are jostling for market share. Among them are traditional banks like HDFC and ICICI, startups like Payswiff (formerly Paynear), Mobiswipe and E-Paisa, as well as wallet companies like Paytm and Flipkart-owned PhonePe, allowing all merchants, including micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), to accept digital payments.

“Yes, it’s a busy space,” concedes Kush Mehra, president APac and MEA region, Pine Labs. “But there’s also plenty of headroom to grow,” he says. While the formal market comprises 15 to 20 million merchants (based on GST filings), only 2.8 to 3 million of them accept digital payments, he points out.

With multiple players, differentiation and innovation becomes key. Mswipe, for instance, started operations with a simple card reader that merchants running MSMEs could attach to their mobile phones. But when they realised that merchants often didn’t park their mobile phones with the cashier all day, they produced an independent device with a number pad and a SIM card slot that also works on WiFi.Vijay Rajora, who manages Photo Funda, a Mumbai-based shop for items like photo frames, printed mugs and tees, upgraded to this newer version about a year ago. “My phone is freed up now,” he says, adding that the advantage of going with Mswipe is that payments are settled the next morning. “With others, it often takes a few days.” Photo Funda paid a sign-up fee of ₹1,500 and now pays Mswipe a monthly rental of ₹350, a far cheaper option than traditional acquirers.

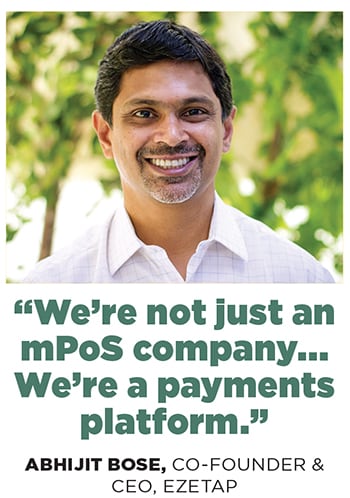

A key feature of devices today is their ‘interoperability’, which means they are able to accept not just card payments, but also UPI-based payments, transfers from e-wallets, net banking, Aadhar-enabled payments (AEPS) and ‘tap-to-pay’ methods using near-field communication (NFC) technology. “We’re not just an mPoS company,” says Abhijit Bose, co-founder and CEO of Ezetap, “We’re a payments platform.”

As digital payments become ever more frictionless, what is also beginning to matter are the additional services offered to merchants. For instance, data that is generated on Photo Funda’s operations (annual turnover of ₹18-20 lakh) is valuable to Mswipe’s partner banks who can assess whether Rajora can afford a loan. Pine Labs, too, offers working capital assistance to its merchants. Hyderabad-headquartered Payswiff Solutions targets the “Bharat part of India”, especially merchants in tier II and III cities, and offers value-added services, such as the filing GST returns through the platform. “We’re the only company to offer this at present,” claims Priti Shah, co-founder and CEO.

Payment solution providers also offer merchants the ability to extend EMI options to customers. Paras Mutha, owner of Arihant Electronics and Furniture Mall in Baramati, a town 100 km southwest of Pune, took up Payswiff’s mPoS solution two months into demonetisation. He paid ₹5,500 for a machine that only accepts card payments (not e-wallets, UPI-based options, etc). Through Payswiff’s partnerships with banks, Mutha can offer EMIs to his customers for purchases above ₹25,000. “Our customers are happy, and sales too have gone up,” he says his monthly turnover is around ₹6-7 lakh.

While Payswiff and Mswipe primarily focus on MSMEs, Ezetap sees a larger opportunity in enterprise clients. “We do cater to SMEs but not directly, as it is essentially a distribution play,” says Bose. “The stronger your distribution network, the better your reach. So we approach SMEs through our partner banks who have that distribution might, especially across smaller cities.” As for enterprise clients, Ezetap looks to provide them with customised solutions. For instance, when state-owned oil and gas company IOCL approached Ezetap, they didn’t just want a digital payment solution, but also a way to plug inefficiencies in the distribution of LPG cylinders. Not only did the cylinders take two to three weeks to be delivered (instead of two or three days), but pilferage was rampant. Through Ezetap’s custom-built EzeDelivery solution, the last-mile efficiency of gas delivery has been upped through a real-time tracking system, deliveries are authenticated through OTPs and customers can pay digitally. Tens of thousands of such devices have been deployed for IOCL, says Ezetap, with over 2 million LPG deliveries being recorded on the platform since its rollout last September.“For Indians to go fully digital, it requires a paradigm shift in behaviour. Ezetap’s solutions have helped us a great deal in this respect,” says Manish Grover, chief general manager (LPG Co-ordination), IOCL.

Even so, challenges remain. India is still a largely cash-driven market. Convincing merchants to go digital is only one half of the task consumers, too, need to be educated. “There are 700 to 800 million debit cards in circulation in India versus about 25 to 20 million credit cards. Yet, only 10 percent of debit cards are used for PoS transactions,” says Pine Labs’ Mehra. “People think it is an ATM card.” While recent government steps such as the waiver of the MDR on debit cards transactions for under ₹2,000 for two years beginning this January are welcome, more needs to be done. Pine Labs has partnered with a couple of issuing banks to provide EMI options on large purchases to a pre-approved list of “category A” savings account customers it was launched six months ago.

As rivals compete to build market share in India’s still-nascent digital payments landscape, it’s the customer who will emerge the winner.

First Published: Jun 11, 2018, 11:48

Subscribe Now