The German Invasion of The Indian Trucking Sector

Daimler is getting ready for a full frontal attack to corner large segments of the Indian truck market, but incumbent Tata Motors isn't going to be a pushover

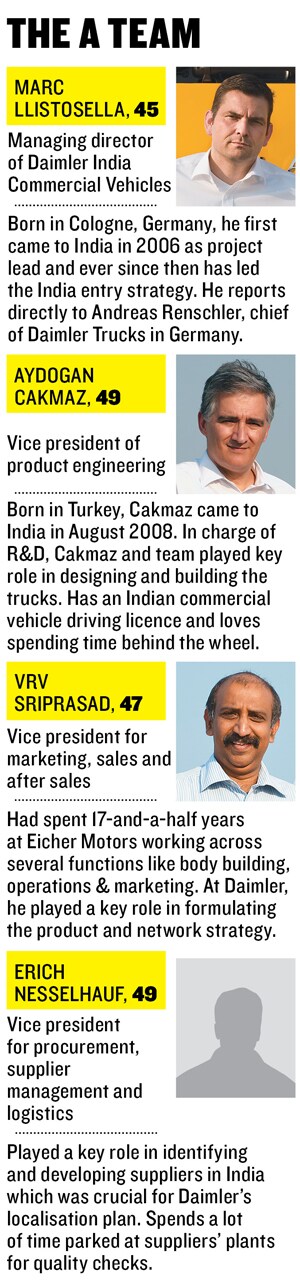

It’s a pity editorial policy doesn’t allow un-parliamentary language. If it did, this story would be a more colourful one because Marc Llistosella (pronounced List-o-say-a) is a colourful character prone to slip often into equally colourful language. But that’s the only way he knows to be. That is also why he now has a mandate from Daimler’s headquarters at Stuttgart in Germany to put up a good fight, however bloody it gets, with Tata Motors and Ashok Leyland.

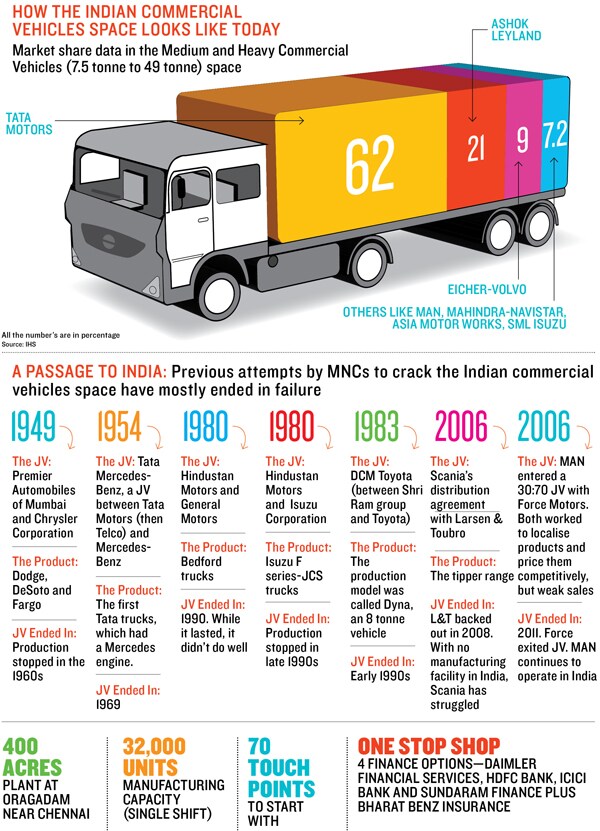

Eighty percent of all trucks sold in India are built by them. Anybody who’s tried to take this duopoly on, has until now, lost to their might. And that includes trucking majors from across the world like Volvo, MAN, and Scania. The American Navistar reckoned partnering with a local company would get it a toehold in the market, which is why it chose to partner with Mahindra. But in the two years it’s been in business, it’s managed to sell just about 1,500 vehicles.

And this market is made of fleet owners who have risen from the grassroots to create large businesses. They know how to run their trucks and make money, but they don’t care two hoots about a global or local brand. “Every MNC came in with an advanced technology perspective, but failed to deliver on the price, financing options for the buyer and point of contact, which is sales and service,” says Deepesh Rathore, managing director, IHS Automotive, a global consulting firm.

The problem is compounded, he says, by the fact that every failed attempt by an MNC adds to fear in the minds of fleet operators. You pay big money to buy a fancy truck, take the risk of switching from a Tata or Leyland and find the company has exited the market.

To put things in perspective, last year, 2.70 lakh medium and heavy commercial vehicles were lapped up by Indians. This is expected to double by 2020. It’s the kind of party nobody wants to miss, but nobody has been able to capitalise on. That these kind of explosive numbers would happen in India was obvious to Llistosella way back in 2005 when he was asked to be part of a team that would identify new markets for the company. By then, he’d moved up the ranks at Daimler, a $142 billion company, by saving the company $132 million by cutting costs and improving efficiencies.

But Llistosella likes a good fight. So the first time he got beaten up as a kid, he swore it would never happen to him again. Aged eight, he started to learn judo. By 12, he’d graduated to Shotokan karate. And at 18, he took up kickboxing, which he practices to date. “I was a street fighter in Barcelona,” he says, where his father hails from. “I know how to fight…but if you feel you’re doing the right thing, and can be proud of it, tears come into your eyes. Not when you go to a press conference and you’re asked questions about a company with big b***, lots of market share and making a lot of money.”

His bosses know that as well—that when it comes to a fight, he will put up a good one. And if things go according to his ridiculously meticulous plans, he can change the landscape of the Indian trucking business. In fact, that’s how he landed the job at Daimler many years ago. Until then, his background was a chequered one. He’d walked out of an investment banking job at CommerzBank because “they were only interested in selling their products, not making their customers rich” he’d tried to set up a venture capital firm of his own. But that fizzled out in two years. And he finally knocked on Daimler’s doors.

The folks there could see the young man had fire in his belly. That said, they were sceptical as well. So they made him an offer: Start out in the boondocks as a salesman. If he did well, they’d hire him. Until then, he’d have to work for free. “I asked, work for free? Who do you think you are?” Llistosella recalls.

The amused folks at the other end of the table told him he ought to be thankful they were making him an offer in the first place. And that all he knew was banking for good measure, they rubbed it in—they told him he’d make a hash of the job. And that’s why they weren’t willing to take a chance or pay him a dime. An incensed Llistosella, just 28 then, took the job, “…and in two years I sold like hell. I sold everything to everybody. You know what? They asked me to stop being a salesman and come to headquarters.”

By his own account, he hated being at the headquarters. “That wasn’t where the party was…So in 2006, it was not them who told me to do this thing in India. I said India is the next market and we have to be there.” Headquarters caved in to his relentless demands and Llistosella moved to Chennai. Daimler India Commercial Vehicles, a subsidiary wholly owned by Daimler was founded a few years later, and launched Bharat Benz last year.

Achtung Jugaad!

Earlier this year, on March 2, Llistosella and his men showcased eight trucks to potential dealers and 2,000 potential buyers who had flown into Hyderabad. “My men weren’t [just] emotional. They were crying for God’s sake!” says Llistosella.

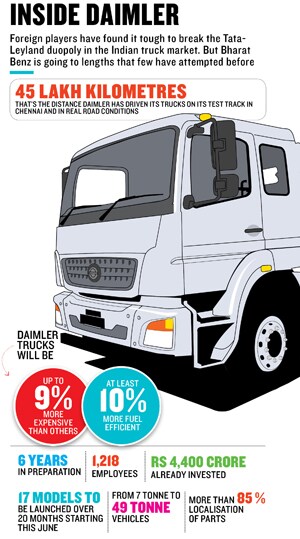

For six years, the team travelled across the country to understand the market so they could build a truck they believed the market would buy into. “I am the real deal,” he says. He’s got the numbers to prove his point. Until now, Daimler has invested Rs 4,400 crore in Bharat Benz, its largest greenfield investment outside Europe.

The folks at Bombay House, corporate headquarters of the $83 billion Tata group, which earns one-third of its revenues from Tata Motors, have been watching Llistosella intently. They have good reason to. A little less than half of Tata Motors’ revenues come from its India operations, with Jaguar LandRover making up the rest. Now, for the India operations, the truck business is pure oxygen because that’s where most of its money comes from. While the passenger vehicle business may sound like the sexier one to most people, fact is, it doesn’t generate too much revenue.

Analysts Forbes India spoke to say that for every one rupee Tata makes selling cars, it makes Rs 5.6 selling trucks and buses. If that be the yardstick, 85 percent of the company’s revenues and a bulk of its profits come from this segment. And don’t forget, two-thirds of all trucks sold in India are built by the Tatas. So if Llistosella succeeds, it would hurt Tata Motors where it hurts most.

Which is why, a couple of years ago, Tata made it very clear to all its commercial vehicle dealers in India that taking up a Daimler dealership was not kosher. And everybody in the network complied. To that extent, Tata is using all of its muscle and experience to prevent the Germans from getting into their territory. A senior Tata Motors official who did not want to be quoted says, “We are absolutely prepared for them. Be it in technology, product or reach, we are taking them very seriously.”

An email sent to Tata Motors questioning how the company is planning to do that got this reply: “We believe that to do justice to your topic, we will need to share with you perspective, examples and information which are of competitive advantage to us. Our play will become apparent to competition.”

On his part, Llistosella knows the Tatas aren’t pushovers. So when he first came down to India in 2006 to study the market with his team of five people, they rented a small cubicle in Gurgaon, which served as the office. That done, they rented a warehouse from the Transport Corporation of India, a logistics company. They called it the “tear down centre” because every truck that existed in the Indian market was driven down here and stripped, and examined to the last detail.

What are its specs? What about the quality of its parts? What does the engine look like? Who supplies it? Everything was looked at, to use a cliché, with the attention to detail Germans are so famous for. After this exercise, which lasted about six months, Llistosella went back to headquarters with his project report and a few startling insights.

It was a world very different from the ones they were used to working in. For instance, in their quest to figure out if Indian truckers like air conditioned cabins, they came up with a horribly sobering insight into India and how the nation works. Many of the truck’s cowl cabin they travelled in had a hole. And contrary to what you’d imagine, it wasn’t meant to cool the cabin down or offer ventilation of any kind. Truckers told them they spent way too much time on the road and the hole was the easiest way to answer nature’s call without taking a break from the wheel. Llistosella had begun to understand jugaad.

He went back to headquarters and said he was ready to begin the India operation. “They said you’re crazy. I said yes, that’s what you pay me for.” Today Bharat Benz has 1,300 people—next year it will have 2,500.  Cracking the indian market

Cracking the indian market

“Theoretically,” points out Rathore of IHS Automotive, “a market where two players hold 80 percent and rely completely on brand recognition is attractive for any global truck manufacturer.” That explains why practically every major truck builder in the world has tried hard to crack open the Indian market. But their carcasses now lie littered all around the Indian landscape.

Their failure has created an aura of invincibility around Tata and Leyland, says VRV Sriprasad, marketing and distribution head at Bharat Benz. His hypothesis is an interesting one. Their aura, he argues, rests on a few propositions truckers have come to believe in over the years, and ones that the duopoly has perpetuated—that you need a massive after sales network across the country to get your truck serviced anywhere that spares ought to be easily available and that any mechanic anywhere in the country ought to be able to fix the beast if it breaks down.

Come to think of it, he says, these aren’t virtues. “What kind of trucks do you build that breaks down so often that it needs to be serviced so often and spares need to be available at every paan shop?” he asks. His contention is a simple one. Trucks built in India are not reliable. And that is why you need a support station every 100 kilometres. So what do you do? Build reliable trucks that don’t break down. As simple as that!He found an ideal foil in the head of research and development, Aydogan Cakmaz, who first came to India in August 2008. When he landed here with his wife and kids, he didn’t know how to speak English. There was no workshop where he could begin planning prototypes. “It was like a startup. We have never done anything like this in any market. Not in Brazil or Turkey, nowhere. It was totally from ground up.”

That he gets into details is an understatement. It took him and his team three months just to figure out why a windshield in a truck breaks when hit by a stone. A cracked windshield is a common sight on Indian trucks. “So we went back to the supplier and asked him to explain. He had met all our standards in terms of design and toughness. But we found that the actual cause of the problem was in the manufacturing process,” says Cakmaz.

For that matter, consider this other curiously Indian phenomenon. When on the highway and the truck is headed downhill, Indian truck drivers have mastered the art of manoeuvring their machines in the neutral gear. Try telling the driver that it’s a safety hazard, and he’ll tell you his focus is on saving fuel. So Daimler designed its engine control unit (ECU) to ensure that when a driver is in cruise control mode, fuel supply to the engine is cut off. Problem solved! Added bonus? No compromise on safety.

But the fear of a breakdown is embedded deep inside the psyche of the Indian trucker. He will want to know if Daimler will be around if his truck breaks down. So what they’ve put in place is a system that can respond to a breakdown call in two hours flat along the Golden Quadrilateral, a highway network connecting Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata.

“We didn’t want a crowd. So we took a call that we’ll have a maximum of 35 dealers with large territories and multiple dealerships. Right from day one, each service station is well equipped to deal with a breakdown. So let’s say if there is an engine problem. No problem…Every effort will be made to reduce downtime,” says Sriprasad. And just to be doubly sure, the trucks have been tested for an astonishing 45 lakh kilometres across various conditions at its test track in Chennai.

I’m not a nice guy

To be fair, Tata Motors has done a lot of spring cleaning, both in terms of the customer experience as well as the product itself. Things like a key account policy which existed only on paper is now taken seriously and engages with customers directly. A key account is defined as any fleet operator who owns 100 trucks or more.

Tata has created a dedicated website for such customers where an operator can access all information on his fleet, maintenance schedules, spares, and discounts among other things.

“The way it works is that there are different discounts for key accounts and they are the first priority of the management. Tata deals with them directly. So let’s say if a key account customer orders 25 trucks. And these trucks are not in stock, but the dealer has orders from 25 retail customers for the same truck, priority is accorded to the key account customer,” says a Tata Motors dealer.

At the dealer level, dynamic discount policies are being put into place. Every first week of the month, the area sales manager together with the dealer decides on the discount for the month. So, for instance, if in a given month it is Rs 50,000—it could be Rs one lakh the other month.

The Tatas have been working hard to bring down the downtime of its trucks to less than 24 hours. “There are 24x7 helpline assistance numbers, schemes for truckers who carry perishable cargo where if a breakdown occurs, Tata Motors offers to move the load to another vehicle, loyalty schemes and discounts on insurance premiums among other things. Tata knows if they don’t do this now, a part of the market could shift to the competition,” adds the dealer.

It is also experimenting with what is internally called the ‘Primazation’ of Tata’s existing product portfolio. That means modernising its existing products using Tata’s learnings from the Prima World Series Trucks, including a variant of this series that is cheaper by Rs 4 lakh. The initiative is being led by its R&D head Tim Leverton. The idea is to plug any gap that exists in the market today. The dealer says Tata wants to send its customers a simple message: Don’t look at competition.

Llistosella remains unfazed. He’s betting on his team to deliver because he’s taken a personal punt on all of them. “Everybody has to confess and get down to his knees and say that I know nothing. Nothing at all and that I am an idiot. I am willing to learn. Yes. If someone is blabbering, someone is pretentious that I know everything about commercial vehicles…thank you very much, you can go.”

The team at Bharat Benz is convinced there are only four things that matter to a trucker: Price, fuel efficiency, network and resale value. Of this, three are in their control and the proposition is fairly straight forward. What they put out will be only 9 percent more expensive than competition to make up though, fuel efficiency will be 10 percent higher and the service network is in place. As for resale value, that is a variable only the market can dictate.

Sriprasad adds for good measure discounts and 30 days credit offered by competition are peripheral ideas. “Insurance will be a big differentiator, no question asked…I don’t want even a single pie going out of my customers’ hands in the unlikely event of an accident. Leave the maintenance to us….You focus on your business.”

On April 18, Dieter Zetsche, chairman of the Daimler management board, will be in India to flag off production at the Chennai facility. The frontal assault is expected to begin in September 2012 when sales open. From then on, over the next 20 months, the company intends to launch its entire portfolio of 17 kinds of trucks that will cater to various segments of the market. These include carrier trucks, vehicles used by cold chains, and mining and construction companies, until its entire portfolio is available in the company.

It’s the kind of task that sounds horribly daunting. “They will fight but I am not afraid of competition. That’s life because then they make me better. So competition is good. As long as the competition is fair. If they play unfair, we can also play dirty. We are street fighters.…The big learning in India is modesty. I am not the American Mr Nice Guy. I am hard working and I really know what I do,” says Llistosella.

First Published: Apr 10, 2012, 06:52

Subscribe Now