SoftBank: Big cheques and balances in India

By betting big money on big businesses, SoftBank is bringing its India strategy in line with its founder Masayoshi Son's global vision

Masayoshi Son, SoftBank’s chairman and chief executive officer

Image: Thomas Peter / Reuters

After a few initial hiccups, a resurgent SoftBank, armed with a $100-billion Vision Fund, is wiping clean its chequered past in India by writing big cheques to the biggest startups.

This is not entirely unexpected, given that Masayoshi Son, the maverick and sometimes impetuous founder of SoftBank, has time and again professed his love for doing things big. “I don’t do things small,” Son, 61, had said in an interview in December 2016.

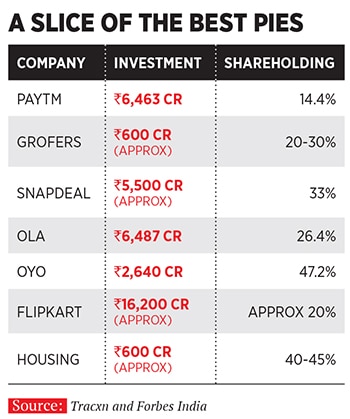

SoftBank has seen a billion dollars invested in online real estate startup Housing and online marketplace Snapdeal sink. But such setbacks haven’t stopped it from bankrolling another online marketplace Flipkart with $2.5 billion and financial services company Paytm with $1.4 billion in 2017.

More big ticket investments by SoftBank are likely to follow, but, this time, it likely to go for market leaders.

This is in sharp contrast to its earlier ploy of cherry picking promising startups in emerging sectors (Oyo in hotel aggregation, Housing in real estate, Grofers in hyperlocal delivery) or even businesses that were number two or three in the pecking order (Snapdeal, for instance, trailed Flipkart when SoftBank first bought into the company in November 2014).

“Earlier, SoftBank’s thought process was to get a foothold in the market and see how quickly they could learn. Now there is a more concerted strategy to dominate the market,” says Vinod Murali, managing partner at Alteria Capital. Murali, in his earlier job at Innoven Capital, had invested in Snapdeal and Oyo. “The number of companies that can absorb the kind of capital that SoftBank will offer is limited, maybe in single digits. But, the next set of such companies is being nurtured and Softbank will have a bigger play then.”

[qt]For them [SoftBank], a couple of hundred million dollars is small change."[/qt]

- Vinod Murali, managing partner, Alteria Capital

Son not only has the appetite and means to do things big, but also the stomach to digest big losses.

“For them, a couple of hundred million dollars is small change,” adds Murali. An executive at a venture capital (VC) firm that has co-invested with SoftBank, and who did not wish to be named, concurs.

“They seemed to have moved on despite losing more than $900 million in Snapdeal. This is a very different DNA, which is very hard to replicate. To give you some perspective, they weren’t hurt as much as we were after losing $25-30 million. That is the kind of cushion they have.”

SoftBank has burnt its fingers earlier, trying to discover hidden gems in India. It teamed up with News Corp-backed venture fund ePartners and Ispat Industries promoter PK Mittal to float eVentures India Holdings in 1999. After investing in about 13 startups over the next four years, the fund shuttered in 2003. It exited three investments, wrote off six and sold the rest to Nexus Venture Partners in a block sale.In 2001, it floated the SoftBank Asia Infrastructure Fund, this time in collaboration with Cisco. This too collapsed after its executives chose to form a new fund called SAIF Partners in 2004.

SoftBank jumped on to India’s consumer internet bandwagon late, in the second half of 2014, by when American hedge fund Tiger Global Management had already established a firm grip over Flipkart, India’s most valuable startup.

But once it entered, there was no stopping SoftBank. In fact, led by Nikesh Arora, the former chief business officer at Google who joined SoftBank as vice chairman in July 2014 and was widely viewed as Son’s heir apparent, SoftBank sometimes gave Indian founders more than they asked for.

Take, for instance, Housing. In late 2014, Rahul Yadav, its 20-something co-founder and CEO, was looking to raise capital to fund his growth plans when he met Arora. By then, Yadav had almost sealed a deal to raise $40 million from investors including Falcon Edge Capital, in a transaction that would value Housing at roughly $150 million. Arora made an offer Yadav could not refuse: A $100-million cheque. Despite the euphoria among investors, a Series C investment that big was hard to find for a two-year-old startup such as Housing.

“SoftBank didn’t want other investors. Since they were in advanced talks with Falcon Edge and others, Housing could not have said no to the other investors as well,” says a person privy to these discussions.

In December 2014, Housing raised $90 million, of which $70 million came from SoftBank and the rest from Falcon Edge Capital and existing investors Nexus Venture Partners and Helion Venture Partners, at a valuation of $235 million. To sum it up, Housing got about $50 million more than it had asked for, with an $85 million mark-up in valuation.

Well, Son is known for writing eye-popping cheques. He has done so in the US and China. But, borrowing a page from his global playbook for India had its downsides. Unlike mature markets such as the US and China, Indian entrepreneurs were still coming to terms with the flush of funds. Exuberance from the likes of SoftBank and Tiger Global Management not only sent valuations soaring, but also prompted them to start spending sprees to gain market share.

Essentially, they didn’t save enough for a rainy day, and when a funding downturn in mid-2015 hit, most Indian startups floundered.

“Because of large pools of capital that came to companies unduly, ahead of time, many of them wired their business models wrongly,” says an executive at another VC firm that had co-invested with SoftBank.

“In a market like India where there is a lot of competition, the companies are loss-making and you don’t know how long the battle lasts. We, as investors, were very happy to have SoftBank, even at the expense of dilution. But, yes, SoftBank and Tiger Global were, to some extent, responsible for the way valuations were perceived in India.”

A questionnaire to SoftBank seeking comments on its India investments did not elicit a response.

In October 2014, a month before investing in Housing, SoftBank had bankrolled Snapdeal, which was then trailing market leader Flipkart (Amazon, which entered India the year before, was still a fledgling), with a $627-million cheque, valuing it at $1.8 billion. The same month, ride-hailing startup Ola entered the unicorn club—startups valued at $1 billion or more—riding on a $210- million investment from SoftBank.

“To begin with, they [SoftBank] were basically trying to find a marquee investor base and do a mark-up on their investments with a 30 percent ownership target,” says the VC executive cited earlier.

Indeed, Nexus Venture Partners, which was an early backer of Snapdeal and Housing, played a key role in introducing SoftBank to Indian startups. Nexus executives Sandeep Singhal and Anup Gupta had earlier worked at eVentures India Holdings.

In the next one year, SoftBank, under Arora, invested further in Ola and Snapdeal. This apart, SoftBank led a $100-million Series B investment in Oyo in April 2015 and a $120-million Series C round in Grofers in November, which were, again, investments disproportionate to the scale and stage of the companies.

The halcyon days didn’t last long. In mid-2015, Housing imploded following a spat between Yadav and his investors. The next June, Arora abruptly resigned. Meanwhile, Snapdeal was losing ground to Amazon and Flipkart, while Grofers struggled to scale up, as its gap with market leader BigBasket grew. Ola, which has since bounced back, was battling Uber’s aggressive advances while Oyo was burning cash to get hotels and customers onboard.

It seemed at one point that Son had bet on the wrong horses.

*****

After the 2015 blitzkrieg, SoftBank spent a quiet 2016, cleaning up its act in India. It refrained from expanding its portfolio and only provided follow-on capital to Oyo ($62 million in August) and Housing ($20 million in two tranches in January and December).

In 2017, SoftBank returned much stronger with the Vision Fund, the largest of its kind in the world, backed by the likes of Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund and conglomerates such as Apple, Foxconn and Sharp.

Armed with a mammoth corpus, of which about $10 billion is expected to be channeled to India, where SoftBank today finds itself in a unique position. Tiger Global, one of the most prolific backers of homegrown startups, with close to 40 investments, is looking for an exit. Some of the large funds, such as DST Global, Steadview Capital and Falcon Edge Capital, have also retreated from India. SoftBank is possibly the only investor who can cut multiple cheques of $100 million or more without batting an eyelid.

The company made the most of this opportunity in 2017. Apart from investing in Flipkart and Paytm, valued at $11 billion and $7 billion respectively, SoftBank led a $250-million funding round in Oyo and participated in Ola’s billion-dollar fundraise. All these firms are market leaders in their respective categories.

It is also in talks to invest in food delivery startup Swiggy and freight startup Rivigo.

*****

Not only has SoftBank emerged as the go-to investor for big startups, it is possibly one of the few firms that can give VC funds in India a much-needed exit, given that public offerings are nowhere on the horizon. It has made some progress on that front already: SoftBank is slated to buy a part of Accel Partners, IDG Ventures and Tiger Global’s stake in Flipkart, increasing its holding to about 20 percent, second only to Tiger Global’s about 23 percent. It also handed handsome returns to SAIF Partners, which sold a part of its stake in Paytm to SoftBank for about $300-400 million.

Meanwhile, it tried to salvage some of its investments, with moderate success. After a futile move to merge Housing with Snapdeal, the former was bought by its NewsCorp-backed rival Proptiger in January 2017. SoftBank also tried to orchestrate Snapdeal’s sale to Flipkart, but failed.

“Softbank takes a proactive approach to working with portfolio companies. In Housing, they deployed resources to help the company. From cash flow management to executive hiring, Softbank’s operational staff was involved in all aspects,” says Ritesh Banglani, a former Helion Venture Partners executive who co-founded Stellaris Venture Partners.

Sometimes, though, this approach rattles investors and entrepreneurs. Following its maneuvers in Snapdeal and Housing, which saw some of its early investors take massive haircuts on their investments, Ola has curbed SoftBank’s rights, possibly to avert boardroom hostilities. It has restricted SoftBank from buying more shares without the approval of founders Bhavish Aggarwal and Ankit Bhati, and the board. Also, SoftBank, which has one board seat, cannot get another if it acquires more than 50 percent preference shares in Ola’s ongoing funding round (having closed a $1-billion round, it is in talks to raise another $1 billion).

“People are slightly wary of Softbank becoming the largest shareholder, but they don’t have much choice as SoftBank has the largest corpus. Most companies will find it hard to deny them an entry,” says a senior executive at another VC firm.

The message is loud and clear: Despite early setbacks, SoftBank will not balk at investing in India. In fact, its India investments are now not just whimsical bets. Instead, companies like Flipkart, Ola and Paytm could be key pieces to its global machinations.

For instance, Chinese ecommerce behemoth Alibaba, which has kept Amazon at bay on its home turf, owns close to 40 percent in Paytm. Alibaba is arguably Son’s biggest success as an investor. He had invested about $20 million in Alibaba at the dawn of the millennium. Its 25-percent stake in Alibaba is valued at about $140 billion. Consequently, SoftBank’s investments in Flipkart and Paytm can be construed as a move to strengthen the anti-Amazon alliance in India. In the years to come, a merger between Flipkart and Paytm to stave off Amazon cannot be ruled out.

Similarly, SoftBank has bought into all major ride-hailing startups across the globe—Uber, Ola, Didi Chuxing in China and Grab in Southeast Asia. A merger between Ola and Uber, which currently bleed each other in India, cannot be ruled out as well.

The play is bigger. But only time will tell if Softbank will reap a rich harvest in India.

First Published: Jan 23, 2018, 09:49

Subscribe Now