Sanjiv Goenka steps out of his father's shadow, into the limelight

Five years after the RPG group split, Sanjiv Goenka has managed to shake up the companies he inherited and acquired

In 2011, Sanjiv Goenka, the younger son of RPG Enterprises founder Rama Prasad Goenka, formally stepped out of the shadow of his father’s business empire by carving out a separate corporate entity: The RP-Sanjiv Goenka Group. The move was the conclusion of a process that Rama Prasad Goenka had set in motion a year earlier, when he engineered a division of the family business between his two sons: Older son Harsh Goenka got tyre manufacturer Ceat, power equipment maker KEC International, IT service provider Zensar Technologies and pharmaceuticals firm RPG Life Sciences, while Sanjiv Goenka inherited the power generation and distribution company CESC (the sole power supplier to the city of Kolkata), retail chain Spencer’s, carbon black maker Phillips Carbon Black (PCBL) and music and television production company Saregama.

However, soon after the division, Sanjiv Goenka (54) realised the senior managements and CEOs of his companies weren’t quite cut out for their roles. They couldn’t walk in step with the culture of superior performance, deadline-driven delivery and the customer-centric focus he had envisioned for the newly-branded RP-Sanjiv Goenka Group.

Senior group executives say, for instance, that the CEO of one of the group’s bigger companies would attend office for a few hours a day and spend more time on his passion for photography. Another company chief would spend many hours out of office tending to personal matters and cancel key meetings at the last minute.

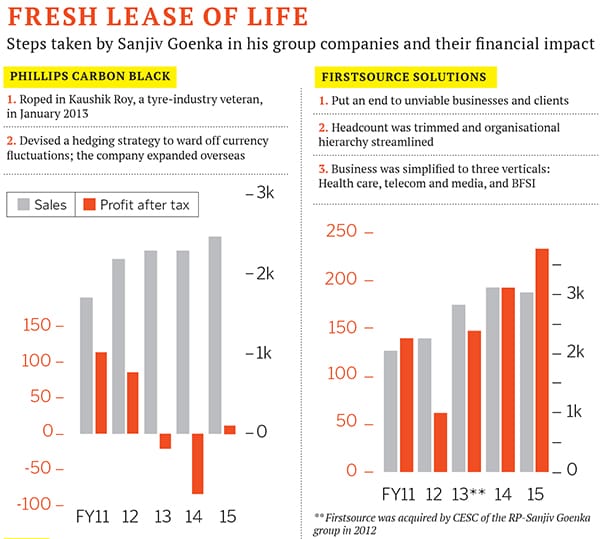

When Goenka took over, profits were slipping at PCBL, Saregama was in the red and some others were losing ground to competitors, even as revenues fell.

Fiercely ambitious, and determined to make his own mark, Goenka decided to put his foot down. He made his intention clear to all his CEOs: Shape up or ship out. Although his stern orders were not received well, the message was loud and clear: Performance is non-negotiable. However, despite his tough stance, Goenka realised some of his CEOs would not mend their ways and began to replace them. “It was tough,” he admits, “but it had to be done.”

Goenka’s hard line was a far cry from his days in the undivided RPG group, where many group-level decisions were taken by his father and elder brother. Back then, he couldn’t always air his views and that left him feeling stifled. But now, he needed to gear up during a sluggish phase of the Indian economy. Although many of his group companies, based in Kolkata, had witnessed the super-growth phase of India’s economy, they had missed out on big opportunities.

For instance, weighed down by years of mismanagement, PCBL— which, the group claims, is India’s largest producer of carbon black, used in manufacturing tyres—reported losses in FY13 and FY14. Neither had the company’s leaders anticipated the high forex losses on account of a higher import bill (90 percent of the company’s raw materials were imported), nor were they prepared for a slowing domestic market, and competition from cheap, coal-based Chinese imports.

Goenka began taking steps to mitigate these issues and hired Kaushik Roy—whom he had met a few years ago—from Apollo Tyres as PCBL’s managing director in January 2013. Before joining PCBL, Roy was managing director of Apollo’s rubber plantation company. An industry veteran, he had studied at IIT-Kharagpur and the University of Tokyo.

Consulting firm McKinsey was also brought on board. Immediate steps were taken to prepare a six-month hedging strategy to ward off currency fluctuations for imported materials sales and marketing teams were formed to cater to overseas markets. Foreign expansion gave the company dollar revenues that helped tide over forex issues and hedged against a slowing local market.

The implementation of this plan, however, was far from easy. New technical teams had to be put in place and an experienced American expert, Eugene Byrd, was hired to start a Technical Competence Centre (TCC) to produce quality products for the global market. A few specialty-grade products are now being tested at the company’s TCC labs at Vadodara in Gujarat, to produce high-margin carbon black that can be used in car paints, and other products.

“We looked at operational efficiencies across all functions, including raw material purchase, finance and marketing. Our first target was the low-hanging fruit so that there would be quick results. Goals were divided into short-, medium-, and long-term projects,” says Roy. PCBL has also tied up with various decanters (storage facilitators)—located near their foreign clients—to stock their products to ensure timely delivery of carbon black. This has spared the clients the burden of stocking up. “Our customer-centric focus has helped us win new clients and maintain good relationships with existing ones. It has helped us keep our rivals at bay, even if they sell cheaper products, and has also ensured higher capacity utilisation at our plants,” says Roy.

The efforts have borne fruit: PCBL’s revenue rose by around 9 percent year-on-year in FY15 to Rs 2,470 crore, and it posted a Rs 11-crore profit in the period, compared to a loss of Rs 86 crore in the previous fiscal.

PCBL is not the only group company where Goenka has steered a transformation. At one of his biggest companies, CESC (formerly Calcutta Electric Supply Corporation), he has taken measures to ensure it remains agile and customer-focussed. Like PCBL, CESC has also undegone a management change. But in this case, Goenka chose an internal candidate to shake up the company.

Aniruddha Basu, a 30-year company veteran and CESC’s executive director (distribution), was elevated to the post of managing director in May 2013.

Since then, several operational efficiencies have been introduced, ensuring minimal downtime in power supply. Transmission and distribution losses have been halved, while a new mobile app and a revamped website help consumers monitor their daily power consumption. Text messages are used to alert customers of power cuts in case of a power failure, emergency generators are kept on standby near hospitals or areas where senior citizens live (CESC has begun making demographic maps of its consumers). Earlier, customers had to wait for weeks for a new connection now that has been reduced to 48 hours from the time of application. The senior management at CESC regularly appears on live chat on social media to address customer problems and technology is being upgraded to create a smart grid (it can identify changes in demand and supply electricity accordingly) with the help of the US Trade and Development Agency.

However, there remains one big concern on the balance sheet of CESC, which has also invited shareholder criticism. Spencer’s—a retail chain that sells food products, apparel and kitchenware—was merged into the power utility firm in 2007, and its losses continue even after many years of operations. Before 2007, Spencer’s Retail was a separate entity in the undivided RPG group, which had acquired it in 1989.

Despite Spencer’s losses, consolidated sales at CESC in the last four years have grown from Rs 6,000 crore to Rs 11,000 crore. However, consolidated profit after tax fell to Rs 199 crore in FY15 from Rs 492 crore a year earlier, due to losses at Spencer’s. Moreover, the idle Chandrapur power plant—the company has four other power plants—acquired by CESC in 2009 added to the loss. “Both units of the [Chandrapur] project [300 MW each] have been commissioned. The project is not generating sufficient power due to pending fuel supply agreements (FSAs) and lack of adequate power purchase agreements (PPAs). Efforts are under way to secure more PPAs and an FSAs with Coal India,” CESC said in an investor presentation recently.

According to a May 2015 report by Kotak Securities, “Retail losses remained largely unchanged at Rs 150 crore and under-utilised capacities at Chandrapur were a drag on CESC’s consolidated performance. Without clarity on whether merchant sales from extant capacities can mitigate coal cost under-recovery in the standalone operations, we are constrained to maintain our ‘Reduce’ rating with a price target of Rs 600 a share.” On July 8, CESC’s shares closed at Rs 567.8 on the BSE.

Goenka is well aware of the threat posed by Spencer’s to CESC’s balance sheet. He has handed over the responsibility of turning around the retail chain to his son Shashwat (25), a Wharton graduate, who joined Spencer’s three years ago. “We are clearly focussed on cost cutting and improving margins than just revenues. We have flattened the organisation and changed hierarchy for quick decision making. We no longer have zonal heads and have shut down our zonal offices to eliminate delays,” says Shashwat, sector head-retail at the group.

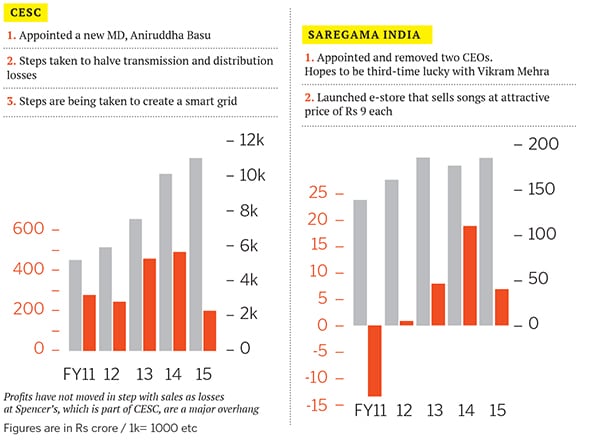

On the advice of McKinsey, Sanjiv Goenka has also ventured into new sectors such as business process outsourcing (BPO), health care, and real estate. Goenka was keen on fast-growth industries without regulatory concerns and where government intervention was minimal. The BPO company Firstsource Solutions was the perfect fit. Though Firstsource was reeling under a debt of $275 million in 2011, due to an FCCB (foreign currency convertible bonds) overhang, it had the potential to turn around. ICICI Bank, which owned the company along with a few other investors (Singapore wealth fund Temasek and financial services and technology firm Metavante), had just brought back Rajesh Subramaniam as Firstsource’s deputy managing director and CFO in 2011 (he had quit in 2008) to steer a revival. It needed urgent cash infusion and someone who believed in Subramaniam’s strategy. Goenka landed the deal in December 2012 and agreed to put in the required capital and clear the company’s debt. Subramaniam is now the managing director and CEO of Firstsource.

On the advice of McKinsey, Sanjiv Goenka has also ventured into new sectors such as business process outsourcing (BPO), health care, and real estate. Goenka was keen on fast-growth industries without regulatory concerns and where government intervention was minimal. The BPO company Firstsource Solutions was the perfect fit. Though Firstsource was reeling under a debt of $275 million in 2011, due to an FCCB (foreign currency convertible bonds) overhang, it had the potential to turn around. ICICI Bank, which owned the company along with a few other investors (Singapore wealth fund Temasek and financial services and technology firm Metavante), had just brought back Rajesh Subramaniam as Firstsource’s deputy managing director and CFO in 2011 (he had quit in 2008) to steer a revival. It needed urgent cash infusion and someone who believed in Subramaniam’s strategy. Goenka landed the deal in December 2012 and agreed to put in the required capital and clear the company’s debt. Subramaniam is now the managing director and CEO of Firstsource.

At the time, Firstsource was facing a breakdown in internal controls and the ecosystem was ripe for someone with a contrarian view. Although clued in to each and every move Subramaniam was making, Goenka gave him a free hand. Subramaniam put an end to business with some clients because the company was bleeding cash by taking up projects in disciplines it shouldn’t. Today, the BPO’s mainstay is customer interaction with services in three verticals: Health care, telecom and media, and banking, financial services and insurance (BFSI).

On the people side, too, there was a massive cleanup and de-layering, making Firstsource a more accountable and ownership-driven organisation. There had been excesses hidden in inefficient hierarchial structures (for instance, each vertical had its own CEO, COO, HR head and so on, with various duplications across verticals and geographies). “When we identified these issues, we were able to let go of a lot of people and that gave a big uptick to our numbers,” says Subramaniam. The strategy has yielded results. While Firstsource’s revenue was Rs 3,100 crore in FY14 with 32,000 employees, in FY15 consolidated revenue was near flat at Rs 3,035 crore despite a reduced workforce of just under 26,000. Profit increased 21 percent to Rs 234 crore in the same period.

At the time of the acquisition, Goenka was quick to spot that Firstsource was at the cusp of a turnaround. Subramaniam had begun making the right moves and the company’s share price had started to inch up after having fallen below its face value of Rs 10. (Goenka bought it at Rs 12.20 apiece.) “Given the turnaround that we embarked on, and the ability to restructure the balance sheet to repay the debt, there clearly was a divergence in the intrinsic value of the company and the purchase price. And I think that through his diligence, Sanjiv picked that up clearly and liked the story at Firstsource. He trusted his instincts and bought the company,” says Subramaniam. The share price was Rs 34.15, as on July 14, after having touched about Rs 45 last year. Goenka’s investment of about Rs 440 crore (for a 57 percent stake) has ballooned to Rs 1,800 crore. Commenting on his boss’s leadership style, Subramaniam says, “He is a patient man, maintains a balanced outlook and deals with good news and bad news in equal measure. He’s a good listener and is willing to learn.”

Another group company that Goenka is trying to revive, but has proved a tough nut to crack, is Saregama India (earlier known as The Gramophone Company of India). For a long time it had posted profits but then its fortunes began to fall seven years ago, and since then it has not been able to recover. Two CEOs have been replaced by Goenka and now it is upon Vikram Mehra, former chief commercial officer at TataSky, to realise the dream Goenka has for his pet company.

The first step Mehra, who joined as managing director this year, took was to launch the Saregama music e-store this June next in line is the launch of its Android app. Music industry revenues have, for over a decade, been plagued by piracy and rapid changes in technology. Mehra has taken the call of selling Saregama’s collection of more than one lakh songs at an attractive price of Rs 9 per song on its website, compared to iTunes’s Rs 15 per song. Once someone purchases a song, the buyer can download it 10 times (compared to three times allowed by iTunes) and get its digital rights management (DRM) for free (the user can transfer the downloaded music from one device to another, which is not allowed by iTunes). “I would rather allow a legitimately purchased song to be shared multiple times, than make it so expensive that customers flock to pirated sites,” says Mehra. He is confident that a large population of music lovers will buy good quality songs legally, at a reasonable price if the experience of online purchase is smooth.

Saregama has another revenue stream: Production of TV shows. Started almost eight years ago, for Tamil channels such as Sun TV, the company has made programmes for Life OK, &TV, Doordarshan and Bengali channels. It currently has seven shows on air. He has recently hired two more senior creative professionals from the industry to ramp up revenues from the TV production business.

Mehra is focussing principally on three revenue streams. One, music sold to telecom companies for ringback tones or OTT service providers such as saavn.com or hungama.com. Two, selling music usage rights for TV shows, TV music channels and radio stations. And three, producing content for TV.

Nursing back to health the sick businesses he inherited, and acquired, was a matter of pride for Goenka. But despite his lofty ambitions, he has been careful not to become a micro-manager. He has allowed his CEOs to run the show in all his companies, yet he is meticulous enough to delve deep into their details on strategy and plans.

The battle that Goenka and his CEOs have waged in the last five years has helped grow the group’s assets from Rs 8,000 crore in 2010 to more than Rs 30,000 crore today. Revenues have also scaled from about Rs 6,000 crore to over Rs 15,000 crore during the same period. Further, last year, Goenka ranked 69, with wealth of $1.4 billion, on the 2014 Forbes India Rich List in comparison, brother Harsh ranked 82, with wealth worth $1.14 billion.

“The first five years were about growth, operational efficiency, restructuring and consolidation. Putting the house in order was the mandate. Now, we’re actually in the next phase of growth,” says Goenka.

The group continues to expand and now includes 15 companies in six different sectors. Last year, Goenka bought a minor stake in the football team Atlético de Kolkata of the Indian Super League. This single investment has lent him a great amount of visibility.

But Goenka is not resting on his laurels. Though some of the group’s companies are not completely out of the woods yet, he is busy devising strategies. The challenge is the next phase of growth and finding new avenues to expand in, says Goenka. “I think it’s time for strategising on allocations between industries with intense government intervention and industries with little government intervention. And that’s a big decision.”

But one thing Goenka does not have to worry about now is capital. Many of the group companies’ performance in the past five years has ensured a steady flow of cash to fund his designs for the future.

More than that, the last few years have also given enough evidence of his ability to stand alone. Goenka has indeed stepped out of the shadow, and into the limelight.

First Published: Aug 06, 2015, 06:16

Subscribe Now