Prestige's Irfan Razack and his Mumbai dream

Having made Prestige a household name in Bengaluru, can billionaire-developer Irfan Razack do the same in India's most expensive and competitive real estate market?

In 1990, when Irfan Razack sold his second real estate project in his home market of Bengaluru for Rs 1 crore, he began planning his retirement. Elated with the money he had made, Razack thought he could spend his days indulging in his favourite hobby—horse riding. But twenty-five years later, the now 62-year-old chairman and managing director of Prestige Group is still hooked on to real estate. “My friend had warned me that making buildings is like a drug. He said, ‘You will become addicted to it’,” says Razack, who heads Prestige Estates Projects Ltd, the group’s flagship company.

A self-professed “clear thinker” who prides himself on being meticulous, he believes that life is about conquering the next big milestone. “Money loses its charm after a while. It is the creativity that keeps you going,” says the billionaire, who, with a net worth of $1.23 billion, ranks at No 77 on the 2014 Forbes India Rich List.

Prestige Estates Projects, India’s second-largest listed real estate company, is on the brink of greater things. Now more than ever, it needs its leader. Retirement is not an option for Razack.

For the first time, in financial year 2015, Prestige has overtaken India’s largest listed real estate developer DLF Ltd in pre-sales (new sales). Last year, the difference between the pre-sales of the two competing companies was Rs 1,424 crore with DLF in the lead. But Prestige ended the recently concluded fiscal 2015 with Rs 5,014 crore in pre-sales compared to DLF’s Rs 3,850 crore of pre-sales much to the surprise of analysts who were initially sceptical of Prestige meeting its new sales target of Rs 5,000 crore.

Now, Razack expects to touch Rs 20,000 crore in pre-sales in the next three years. And this time around, everyone, competitors included, is paying attention.

To put things in perspective, prior to its initial public offering (IPO) in FY09, Prestige had recorded revenues of Rs 889 crore. Since 2010, its market capitalisation has grown from Rs 2,000 crore to about Rs 10,000 crore currently. Its subsequent rise in these last six years has coincided with DLF’s decline in growth. DLF’s market capitalisation has been on a downward spiral from a high of Rs 2 lakh crore in 2008 (a year after its IPO) to approximately Rs 22,000 crore.

These comparisons don’t sit too well with Razack. “We are the number two developer by default, rankings don’t matter,” he says.

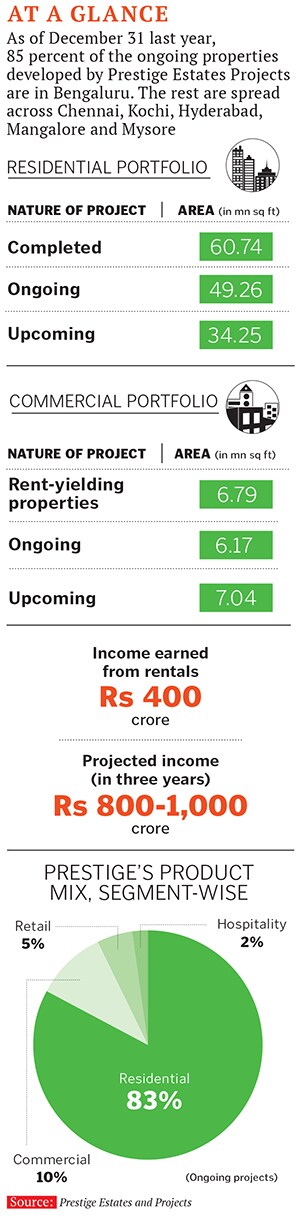

But how did he ride the crests and troughs of the real estate market? For nearly three decades, the Bengaluru-based developer built an enviable portfolio by focusing mostly on his home turf (85 percent of its ongoing projects are in the city) compared to its larger rival DLF, which has projects across India. Luck had a hand in his success, too. Bengaluru, along with Mumbai and Delhi, is one of the top three residential property markets in India, and has held steady unlike the National Capital Region (NCR) where DLF has most of its projects.In terms of revenue, Prestige pales in comparison to DLF. The New Delhi-based real estate company ended FY15 with Rs 8,168 crore in revenue compared with Prestige’s modest estimated revenue of Rs 3,200 crore for FY15. Prestige was scheduled to declare its audited financial results for FY15 on May 30, 2015 (after Forbes India went to print).

What has largely gone unnoticed, however, is that a substantial portion of the Bengaluru developer’s sales have not yet come in for revenue recognition. Real estate firms recognise revenues once their projects reach the threshold limit of 25 percent completion. Because many of Prestige’s projects haven’t reached that limit, the company is sitting on unrecognised revenue (sales made but yet to come in for recognition) amounting to Rs 8,377 crore as of December 31, 2014. Much of these sales will kick in by FY16.

Not that Razack is sitting around waiting for the numbers to kick in. He has far bigger plans.

The Litmus Test: Mumbai

His inbox is flooded with offers from landowners from India’s most expensive real estate market, Mumbai, asking him to consider a partnership with them for projects in and around the city. This is not the first time that the company has spoken about expanding its presence beyond the south, but there is more reason now to take note of its intent to become the new kid on Mumbai’s block. “Mumbai will be a game-changer for us. Each square foot we sell in Mumbai is worth 10 sq ft in Bengaluru. In terms of value, getting one project right in Mumbai is equivalent to getting ten projects right in Bengaluru,” says Venkat K Narayana, executive director-finance and chief financial officer, Prestige Group.

Razack admits that his ambitious Rs 20,000 crore pre-sales target can only be achieved if the company expands its geographical boundaries. He believes that Bengaluru has “limited potential for growth”. Mumbai (and satellite towns like Navi Mumbai) will be central to the company’s future. After all, it is a high value market unlike South India. At the same time, he is wary of being seen as a local developer trying to become a ‘national builder’. “Let’s just say that we think we can go beyond our existing markets,” says Razack, who was recently appointed chairman of the realtors’ apex body, The Confederation of Real Estate Developers’ Association of India (Credai).

There is wisdom in his restraint. Adhidev Chattopadhyay, an analyst at Elara Capital, has a cautionary tale. “We have seen that whenever a real estate company has stepped outside its market, it has not done well. Look at Sobha Developers,” he says, citing the Bengaluru-based developer’s Gurgaon project, a villa community called ‘International City’. “It is struggling in the National Capital Region.”

Razack is aware of the pitfalls of expansion. He was cautious even during the 2007 real estate boom when other developers had tried to adopt a pan-India tag. His restraint also stems from the belief that all real estate is local. As Narayana says, “You can do real estate development only in a city where you can drive around and not be driven around.”

But for Mumbai, Prestige will have to change the way it thinks.

In the early years, even before the IPO, Prestige had decided to focus on markets close to Bengaluru. “We felt that real estate projects need to be monitored, and did not want to delegate land buying to someone else. The best we could do was to expand to neighbouring states that did not have large homegrown developers,” says Narayana. Over the years, Prestige moved into the Mangalore, Kochi, Goa, Hyderabad and Chennai markets. The proximity of these cities to Bengaluru made it easy to monitor projects. It may have to alter the way it functions if it moves beyond the south.

In Mumbai, the developer will look at under-pricing as a strategy to draw market attention, even if that means settling for a lower profit margin. “Our philosophy has always been to price it right, sell, get customer money and complete a project, or you end up selling less, taking loans and enriching the bank,” says Narayana.

Prestige has identified three issues in Mumbai’s real estate market: Delivery delays, quality and pricing. “If we can solve even two of them, we will be instant winners,” says Narayana, who has played a key role in Prestige’s fundraising, including its IPO.

That will be easier said than done. Amit Bagaria, founder-chairman and chief executive officer of Bengaluru-based property consultant Asipac, says it will take Prestige at least seven years to establish trust in the Mumbai market. “It will have to deliver four to five projects to gain people’s trust,” he says. It doesn’t help that the Mumbai market’s sales over the last 18 months have been lacklustre.

And, here, Razack’s equation with landowners will be critical, especially because Prestige follows a joint development model where it partners with landlords and shares proceeds from a project sale with them. “A few customers of my commercial projects want me to come to Mumbai,” says Razack. “We have told them that if they have a plan, we can do something.” The developer is even open to acquiring land in Mumbai.

It helps that Prestige is the most sought-after developer among landowners in Karnataka’s capital. Reason: Razack’s reputation for being a fair dealer. “He brings a humanitarian touch to everything he does. For him, his word means everything,” says Juggy Marwaha, managing director, South India, Jones Lang LaSalle (JLL) India, a real estate consultancy firm.

Marwaha dealt with Razack as a competitor for 11 years from 2002 to 2013 when he used to work with Bengaluru-based real estate firms Mantri Developers and RMZ Corp. “I know of this one deal where a developer went to a family that owned land in Bengaluru only to be told by the landlords that they would rather do business with Razack even if he gave them five percent less by way of revenue share,” says Marwaha.

Every significant business opportunity that has come Razack’s way has been because of his relationships with people. His first-ever joint development project in 1985 was with his father-in-law, Abdulla Jaffer, who wanted to sell property on Infantry Road, Bengaluru. Razack convinced him that instead of a one-time sale, the property should be converted into a commercial building (now Prestige Copper Arch) to yield lifetime rentals.

Prakash Shetty, a land aggregator and promoter of the Goldfinch Group of Hotels, who has known Razack for the last seven years and is partnering with Prestige on an under-construction 100-acre township (Lakeside Habitat in Whitefield), says: “Irfan takes care of the landowners’ interest as well as that of buyers. I have some land in Panvel that I have offered to him.”

This show of faith can be attributed to the fact that many landowners and investors have seen Prestige Estates Projects ride out the real estate slump of 2008—and come out on top. (In Bengaluru, home prices fell by as much as 20 percent and sales volumes were down by 10-40 percent.) The Survival Strategy

The Survival Strategy

In hindsight, Razack believes that he got three things right. First, Prestige did not go pan-India. It executed a controlled geographical expansion in Chennai and Hyderabad. Second, it diversified its business portfolio and launched luxury projects (Rs 4-8 crore) at a time when the interest-rate-sensitive mid-income housing was performing poorly. Third, annuity income proved to be the company’s saving grace.

Four years ago, Prestige created an annuity income portfolio from its commercial properties to secure consistent cash flows. Today, its annuity income is about Rs 400 crore and is expected to double to Rs 800-1,000 crore in three years.

In October 2010, when Prestige needed money for expansion, it went for an IPO. It was possibly the worst time for a real estate developer to do this. “We were guilty in any investor meeting unless proven innocent because the reputation of builders was so bad,” says Narayana. Nevertheless, Prestige raised Rs 1,200 crore. A few months after its listing, the markets tanked. Razack and his team had to act quickly.

Before investors could offload Prestige’s stock, Narayana assured them that every single penny they had invested had gone into the company. “I told them that neither mine nor my promoter’s lifestyle had changed. We have not bought jets or homes or cars. I told them that they would see the results of their investment.” In other words, Prestige held itself accountable for every rupee that had been invested into it. It started releasing detailed presentations to update investors on the company’s performance and progress of projects.

It is also one of the few companies in the real estate space that regularly gives sales guidance, collection guidance, launch pipeline, completion guidance and rental income guidance. The strategy worked.

The IPO money came in handy too. At a time when the rest of the industry didn’t have cash, Prestige was able to do land deals on its terms and that helped in capitalising opportunities. In 2011-2012, when interest rates stopped rising, it went back to mid-income housing and launched 40 projects with 20,000 apartments.

The company’s financial health is better than that of most of its peers, but its rising debt is a cause for concern, say analysts. Its net debt is Rs 3,016 crore (as of December 2014) and the debt to equity ratio is 0.72. The idea is to be a debt-free company, and there are plans to pay off loans from cash flows that will accrue from an increase in its annuity income. “In the next three years, we should be cash surplus,” says Razack.

The company has acquitted itself relatively well in the BSE too: Since its IPO, the share price of Prestige Estates Projects Ltd has increased by 30 percent, and was trading at Rs 268.50 as of May 21, 2015.

A large part of Prestige’s success can be attributed to the fact that Razack understands land deals.

From Apparel to Land

Like many large corporate houses in India, the Prestige Group is a family-run business. Nine members of the Razack family work within the group, but it owes its real estate savvy to Irfan Razack and his younger brothers, Rezwan (joint managing director of Prestige Group) and Noaman (director at Prestige Group). In the 1980s, before they became developers, the brothers used to trade in land.

At the time, retail clothing was still the Razack family’s mainstay. Irfan’s father Razack Sattar had opened a men’s clothing store, Prestige Fashions, in 1957 on Bengaluru’s Commercial Street. The family still owns the store, now a 20,000 sq ft retail outlet that deals exclusively with men’s fashion. “We have got two stores, one each in Bengaluru and Chennai, and are planning to get into other southern markets soon,” says Noaman, who is also managing director of Prestige Fashions, one of the companies in the group.

The shift in focus from apparel to land and finally to property development took place over 30 years ago, and can be traced back to 1981, when the family sold its ancestral property on Infantry Road for Rs 75,000. “We started buying and selling land,” says Rezwan, who was 30 at the time. “We did a whole lot of trading of sites in Indira Nagar and Koramangala in Bengaluru between 1981 and 1985. There was a time when we knew every land seller in Koramangala.”

In 1985, when tax rules related to land sale made trading difficult, the brothers started Prestige Estates Projects Ltd. “We moved from trading to real estate development,” says Rezwan. It was a timely move that coincided with the information technology (IT) boom.

Since then, Prestige has developed 65 residential and 39 commercial projects in Bengaluru alone. In total (including Chennai, Mangalore, Kochi, Hyderabad and Goa), it has completed 184 projects spanning a cumulative developed area of 60.74 million square feet. Over the last five years, its sales have grown at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 30-35 percent at a time when the real estate industry’s growth has been stagnant.

Bagaria calls Prestige a volume player. “It follows Maruti’s strategy and not BMW’s,” he says, reiterating that the developer relies heavily on volumes for growth. “Every year, it consistently launches 12-15 projects. It sells lower than market prices compared to other A-grade players. It follows this strategy of selling cheap, but selling fast.” (The bulk of the property it sells is in the mid- to upper middle-income category with prices ranging from Rs 30 lakh to Rs 2 crore.)

The Endgame

Razack shares a rare warm camaraderie and maintains business relationships with many of his peers. RMZ Corp and Prestige are undertaking a yet-to-be named Rs 1,800-crore luxury residential development together in Bengaluru. JC Sharma, managing director of Sobha Developers, says, “Irfan has made us all proud by the way he has scaled up and become the largest real estate seller today.”

There are, however, concerns about the future of the Prestige Group, especially once Razack steps down. Marwaha says the succession issue is a downside. “Irfan is running the business at a speed of 180 km. Whether the story can continue is the only risk to the company,” he says.

The Razacks are planning to move their shareholding in the company to a family trust and will form a family council with an outside member to draw a succession plan. “We are not timeless. At some point, we will phase ourselves out,” says Razack.

For now, almost every member of the family is involved in the business. Razack’s younger sister Anjum Jung (45) is executive director-interior design and heads Morph Design Company, which is part of the Prestige Group. Her husband Omer Bin Jung (47) heads Prestige Leisure Resorts. The third generation is represented by Razack’s daughter, Uzma (36) and her cousins, 35-year-old Faiz Rezwan (executive director-contracts and projects) and Zayd Noaman (24).

Razack wants the business to grow in a measured fashion. “The scary thing is you become big, but while growing you can’t afford to take the eye off the ball or you will get bowled out,” he says. In 2008, a 16-storeyed block under construction in its 100-acre township project, Shantiniketan (in Bengaluru), collapsed leading to many questions over the quality of the raw material used.

An incident like this could spell doom for the company’s Mumbai plans. “If you are not focussed and choose a wrong contractor for large jobs, things can go wrong,” says Razack. Lesson learnt. Prestige now has its own contracting firm for small and medium jobs. “I will not start with a bang in Mumbai and create a mess. We will test waters and see how dynamics work in a region,” he says.

Even the most carefully prepared plans do go wrong but Razack shrugs off the ‘what ifs’. “I will exit if it doesn’t work,” he says. “I have no ego.”

Till then, there is no talk of retirement. The horses will have to wait.

First Published: Jun 09, 2015, 06:44

Subscribe Now