Poddar Developers Rides High On Low-Cost Housing

Mumbai-based Poddar Developers intends to stick it out for the long haul in the low-income housing business. After all, it could be the next big realty thing given a 24.7 million unit shortage

Two-and-a-half hours north-east of Mumbai, in the distant exurb of Badlapur, the outline of a vast new project is taking shape. The Dipak Kumar Poddar-promoted Poddar Developers, which has positioned itself as a low-income housing specialist, is working on a 70-acre township which, when complete, will comprise 3,000 apartments in Phase I these will be made available over three phases and have been launched at an affordable Rs 1,899 per square foot.

Walk around the complex and you will be hard-pressed to slot it as a low-cost venture. The first lot, recently handed over to occupants, is bundled with parks, a cricket pitch and a club house—amenities you would expect to find in a plush housing project. Also, at first glance, these apartments seem to have a better finish than traditional low-income housing. The walls are well plastered, the toilet fittings are from reputed brands (they come with a warranty) and the plumbing appears to be as good as that in any apartment block in south Mumbai.

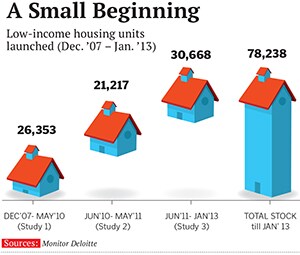

This is a shift in approach towards low-income housing, long shunned by developers due to low margins. The last three years show that a start, albeit a diffident one, has been made. The figures (research by Monitor Deloitte says that 78,000 units have been launched in this period) point to a number of developers taking the first steps. With the ministry of urban development estimating a 24.7 million unit shortage in low-income housing, the opportunity is huge.

There are also signs that some developers are beginning to understand what it takes to stay in the game. The business requires a different skill set from what traditional developers have. That is the reason why big names like DLF, Unitech and Lodha have so far stayed clear of this sector. (Tata Housing has a successful low cost business but that is part of a larger portfolio.) Poddar, which has launched four projects in the outskirts of Mumbai, has plans to start at least half a dozen more in the next two years. Vastushodh in Pune and DBS in Ahmedabad are carving out similar niches. “These developers are taking baby steps in the business and, in time, have the potential to become large national brands,” says Vikram Jain, who leads the affordable housing practice with Monitor Deloitte.

What makes Poddar well-positioned to capitalise on the opportunity? “A lot of people get into this business and then migrate to building expensive houses. Rohit [Dipak Poddar’s son who is leading this business] is one of the few people with a laser-like focus only on this segment,” says Madhusudan Menon, chairman of Micro Housing Finance Corporation. Since Poddar’s first project launch in Karjat in 2010, Rohit has spent time learning the business. Now, as he prepares to scale up, the company will have to prove itself as a viable, profitable long-term concern.

Spotting the Opportunity

Rohit Poddar, a youthful 42, got into real estate by accident. His father owned multiple mills in Mumbai’s Parel area. In 1992, after he completed a bachelor’s in civil engineering, economics and management from King’s College, London, he had no intention of coming back. He had grown up in an era of 3 percent growth and after he landed a trainee position with Goldman Sachs, returning to India was not even an option.

That changed in 1994 when his grandfather summoned him back to work in the family business. But the textile industry had never excited him instead, he began learning about the green trade which had always fascinated him. From 1996 to 1999, he shifted base to Shanghai to work with textiles made from organic cotton. A brief dalliance with the tyre trade followed. And then, in 2002, he bought his first land parcel at Alibaug, near Mumbai.

It was around the time India was emerging out of a real estate slump. For the next 10 years, the market was on steroids and land aggregation became a huge business.

Rohit realised there was significant arbitrage in converting land from agricultural to commercial. That was, and remains, hard work. He would spend time with groups of farmers, convincing them to sell land. These parcels were outside large cities, relatively inexpensive and could support housing projects. But they couldn’t support the kind of high-margin developments of the large cities. This got Rohit thinking. “Since we understood land and had a commodity manufacturing background, I started to see how we could use these skills,” he says.

The Low-Cost Push

Poddar Housing (the brand for Poddar Developers’ projects) finally broke ground in March 2010, on two parcels totalling 14 acres in Karjat. Rohit had studied the model and appreciated the differences with conventional housing projects where the developer buys land and constructs slowly in low-cost developments, the key is to get out quickly. According to Jain of Monitor Deloitte, in a traditional housing project, construction accounts for around 20 percent of sale price as opposed to around 50 percent in low-income housing.

The typical developer doesn’t really worry about construction delays. Houses are sold in tranches and a delay enables a higher price. Buyers too are happy with the increasing capital value of the house. But in low-income projects, lags can lead to increasing interest costs. In fact, they can be the difference between profit and loss. Also, buyers who invariably pay monthly instalments can’t afford a delay of even a month or two. “Only those with an industrial mindset can succeed in this business,” says Jain.

Rohit also worked on understanding the consumer demographic. First, he was clear that just because his buyers belonged to the low-income category, did not mean they deserved a lower standard of living. Take TVR Kumar, for instance, who moved to Badlapur after retirement in August. A retired naval sailor, he wanted to live in peaceful surroundings. “Other developers in Badlapur have constructed standalone apartments without any amenities or parking. At least here I have place for my grandchildren to play,” he says.

The development also has its own water supply and sewage treatment plant. Further, it is constructed close to an industrial park. This allows owners to rent out their flats. As most buyers can barely afford two-wheelers, all of Poddar’s projects have bus transport to the nearest station.

According to Nilesh Kadam, senior sales executive at Poddar Developers, 40 percent of total sales were to investors who either sell or rent once granted possession.

Small kirana-like shops are sold in the last phase, allowing the developer to charge a high price.

The next step was project management. In order to explain how his skills were severely tested, Rohit drives us to Karjat and takes us around the development. Six months into the launch of the project in 2010, there was a ban on local sand mining. Construction projects were hit and work at the site came to a standstill. Even after the ban was revoked, poor quality sand led to problems like rain water seepage through the apartment walls. The project was delayed for a year and the company is still working on rectifying the seepages.

People familiar with the company say Poddar lost money on this development. In his rush to fix his financial position, Rohit compounded the problem: He sold all the units in one go. This meant that when the price rose, he could not reap any benefit. It was an issue he quickly fixed in the next project. “What I learned from Karjat was invaluable,” he says.

Rohit realises that the main reason why projects lose money is because of the developers’ inability to complete them on time. With traditional construction techniques, delays are inevitable. Sometimes materials don’t arrive on time. Labour is in short supply and expensive during the harvest season. In order to hedge against the inevitable slowdowns in work, Poddar plans to construct a large percentage of apartments using prefab techniques, which involve a degree of off-site assembly. While this is 25 percent more expensive, it offers the developer some safeguards.

Marketing the project presented another challenge. Advertising in an English language newspaper was a strict no-no. Instead, Poddar chose local publications. Ads were also placed at train stations. Buyers were encouraged to visit the site and assess a sample house.

For a lot of them, financing is an issue—so the company tied up with a dozen loan providers. (It even got Deepak Parekh, chairman of Housing Development Finance Corporation and the country’s largest home loan provider, to inaugurate the Badlapur and Shahpur projects.) Rohit hired people from housing finance companies as they are best-placed to make sure loans are disbursed and the right answers are given to questions like: Which company should they send a particular application to? How fast will a particular company sanction a loan? What type of buyers will some lenders not make loans to?

Scaling Up

Poddar Developers is now four projects old and Rohit says he is in the business for the long haul. His company follows what he terms as prudent accounting norms, which means that he doesn’t realise any revenue until the project is delivered. In the quarter ending June 30, 2013, Poddar recorded a top line of Rs 25 crore and made Rs 9 crore in profit.

While construction work is on auto pilot, Rohit, a yoga fanatic, is now focusing on growth over the next decade. He hits the road at least once a week, in search of new land parcels that can be developed in the next few years. At present, the company has a bank of 100 acres of land—this is only going to expand. He is making outright purchases as well as signing joint development agreements with landowners.

In order to arrange finance for customers, Poddar also plans to get into the housing finance business. While this proposal is still at a preliminary stage, Rohit says the idea is to also lend to customers at rival housing projects. This is something Happy Home Finance Company, which is part of Value Budget Housing Corporation, is also looking to do. Housing finance companies that cater to low-income consumers reported growth in excess of 25 percent a year (on an average) in 2013. The most prominent is GRUH Finance, an HDFC subsidiary, which grew by 22 percent last year.

For now, Rohit is working hard on the art of completing projects quickly. He has managed to finish the Badlapur development in two years but, for a decent operating margin, he needs to target 18 months or less. He is also cognisant of rising costs and the fact that rising sale prices now threaten to make houses unaffordable for some sets of consumers. Replicating the model over millions of units is the only time-tested way to succeed. But he is confident.

“My business, in the years to come, won’t be judged as a realty business. It will be like any consumer business with a steady growth in top line and profits. The next year’s numbers will always be better than the previous,” he says.

First Published: Nov 08, 2013, 06:59

Subscribe Now