Piramal's Quest for a Blockbuster Drug

When most pharmas are shying away from high-risk drug discovery, Piramal Healthcare is going for it full steam. Has it found a new way?

It was 10 years ago that Somesh Sharma decided to leave the entrepreneurial haven of California and relocate to Mumbai. He’d had an eclectic career in academics and as an entrepreneur, with stints at medical schools at Harvard and Stanford, and three entrepreneurial ventures behind him. But he had one ambition left: To develop a new drug at a fraction of the cost that big pharma incurs. A headhunter had tracked him down for an interview at Piramal Healthcare. Sharma, who is now chief executive of drug discovery and development at the company, recalls that he went through more interview sessions here than he had in his entire 30-year career in the US.

Chairman Ajay G Piramal and director Swati Piramal may have grilled him over numerous rounds but in the end both sides wanted shots at the same goal. “I told them it’d be 10 years before they’d see any fruits of their labour, and to their credit, they stuck to their guns,” says Sharma.

“They should get very high marks for their commitment to R&D. This business requires a lot of investment and even more time to market the beauty for Piramal Healthcare is that Ajay is willing to employ some patient capital here,” says Jasmin Patel, venture partner at Aarin Capital and former managing director at Fidelity Growth Partners India.

Swati Piramal, a doctor by training, began building the R&D team in the early 2000s, with Sharma at the head. Then, in 2010, came the killer deal: Abbott Laboratories bought Piramal’s domestic formulations business for $3.8 billion. With coffers full, the promoters’ drug development ambition got a booster shot. (Some of that money is temporarily parked—$1.2 billion in Vodafone—and some will find its way into new ventures in financial services, real estate and defence technologies.)

Results are beginning to show now.

In April, the company got European regulatory approval to sell BST-CarGel, a drug for treating patients with cartilage injuries of the knee. The drug came into its portfolio when it acquired Canadian startup BioSyntech in 2010. The potential market is $200 million in the EU alone.

In April, Piramal Healthcare also acquired the molecular imaging unit of German pharma Bayer, which comes with a portfolio of imaging tracers. (Molecular imaging measures biological processes at the molecular and cellular levels.) One molecule that’s closest to the market is florbetaben for diagnosing Alzheimer’s. The market for florbetaben is estimated to be $1.5 billion. The company will apply for regulatory approval later this year. In May, it acquired Decision Resources Group (DRG), a US-based healthcare data services company for $635 million.

These are calibrated steps in transforming Piramal Healthare into an integrated pharmaceutical company with branded products. Molecular imaging is complementing standard treatment and its market is expected to cross $6 billion by 2015 DRG has an addressable market of $5.7 billion.

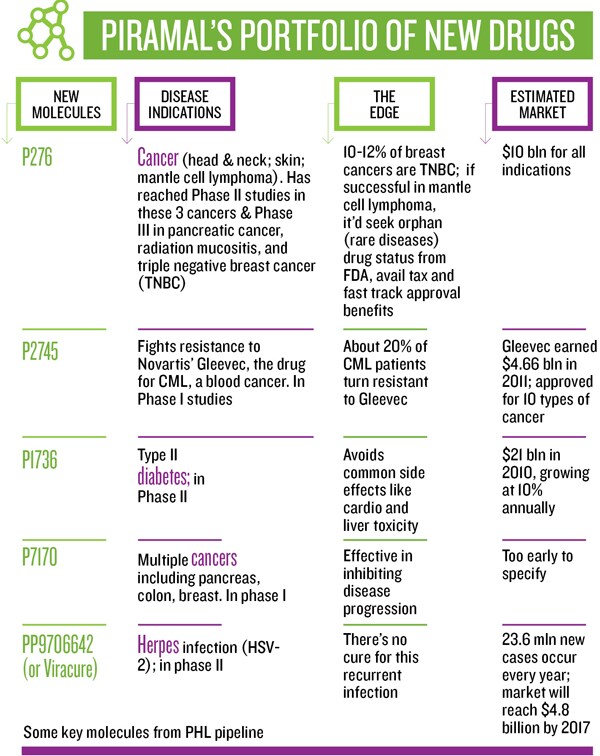

Inside the company, excitement and tension is building up as one of the flagship anti-cancer molecules, P276, which is being tested for multiple cancers in three countries, enters phase III trial in India—a first from any Indian company. It has a market potential of $10 billion and the outcome may prove to be the wind beneath the company’s wings—or it could just as well take some out of its sails.

Swati Piramal is aware of what’s riding on it. A New Chemical Entity (NCE) business today is counter intuitive. Almost everyone is running away from it. Big pharma is investing less in drug discovery because it is consistently hammered by the capital market due to reduced R&D productivity (very few blockbuster drugs are hitting the market) Indian companies lack experience and deep pockets. One exception is Glenmark, but it follows an out-licensing model (where it gives bigger pharma companies licence to its molecules once they reach a certain stage).

“Everybody in India is out of it. Either we are fools or we know something that nobody else knows,” says Sharma.There are many positives to Piramal Healthcare’s approach but this is a portfolio game that needs enlightened asset selection and risk mitigation, says Patel. Sharma agrees and points to his portfolio

Globally, oncology is the fastest growing segment, and according to IMS Health, it will continue to be until 2020. The market is estimated to reach $75 billion by 2013. With six anti-cancer molecules in clinical trials and more in other therapeutic areas joining the pipeline, Sharma says one or two molecules will enter late stage studies every year.

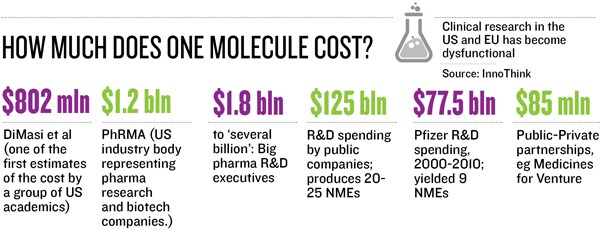

Some of these trials, if successful, may not yield multi-billion-dollar opportunities, but the Piramals have the volume game in mind, targeting niche segments. A new drug, at a cost of $1-2 billion, reaches less than 5 percent of the world population a lower-cost drug, at $100 million per NCE, would mean better access to a larger population and “price into volume will yield good enough profit to be ploughed back into research”, says Piramal.

This also ties in to the fact that the “pharmerging market”—less developed countries—is going to drive almost 45 percent of the global pharmaceutical market. But Piramal may have a perception battle on her hands: Many analysts think the group’s healthcare story is over.

The NCE business is not for the “faint hearted”, says Piramal. “A decade ago they said, ‘If you invent, you can’t patent, as there are no patent attorneys’. We got past that. Then they said, ‘If you patent, you can’t do trials in India as global regulators don’t accept this data’. Today our trials run in five continents we have 360 patents and 16 NCEs. We have moved step by step.” So far, the company has invested Rs 1,200 crore and has 12 molecules in clinics. At about Rs 100 crore/molecule-in-clinic, it’s a fraction of the cost that a big pharma would incur in getting this far.

“If you are developing niche or orphan [rare diseases] indications, then it is possible to get an NCE to market within $100 million if most of the development work is done in India. However, this is cash expense and doesn’t include the opportunity cost,” says Glenn Saldanha, chairman and MD of Glenmark.

The Piramals’ strategy has been to look for reverse brain gain (15 percent of nearly 400 R&D folks have returned from overseas) mine India’s rich biodiversity for novel molecules (most of its molecules are from natural products) look for innovation and technology platforms that cut cost and time (for example, new animal models for screening).

More importantly, having Sharma at the helm has ensured that discovery isn’t just managed with Six Sigma processes. “Somesh is a fantastic colleague. He allows people to be bold and creative,” says Ram Vishwakarma, director, Indian Institute of Integrative Medicine in Jammu. He spent nearly four years at Piramal Healthcare. It’s the best R&D lab in the country, maybe even Asia, he says. “The Piramals have built a great organisation—not an easy thing in India where people often want to rule,” he says, emphasising that he is no longer an employee and doesn’t consult for them. Vishwakarma believes the company has a “healthy” pipeline and one of its finest assets is its vast library of molecules from microbes and plant extracts.

Three years ago, the company signed a partnership with nine Indian institutions to build a natural products library, in addition to 50,000 compounds that it already had. Some 265,000 microbes have been identified and molecules of potential therapeutic value are now being isolated. In this equal revenue- and IP-sharing association, Piramal Healthcare has the first right of refusal, says Arun Balakrishnan, senior VP, external liaison and screening.

Low-cost drugs, says Piramal, is about doing things innovatively to reduce cost and failure rate of molecules. For instance, through phenotypic screening and using the Zebrafish model that the company has developed. In phenotypic screening, molecules are tested directly on cells of interest—say cancer or pancreatic cells, or on animal models. This contrasts with the traditional, lengthier, method: First find a target, look for a drug and then see if it works.

The Zebrafish model could help Piramal Healthcare convert promising molecules into safe market-ready drugs, as it helps identify harmful properties of new compounds early. It reduces an assay time from 30 days to seven, and cost from $4,000 per compound to $80. As a validation, Piramal’s molecule targeted at type II diabetes looks promising in phase I, as it doesn’t have the common side effects. (Type II diabetes has been sidelined by most pharma companies due to serious post-sales side effects, even though the global market is growing at 10 percent and was worth $21 billion in 2010.)

As the molecules progressed, the Piramals needed to address the last mile challenge—of clinical studies. They wanted someone with global experience and so, last year, Alan Hatfield came on board. He had just retired as head of global clinical development at Novartis, and had overseen the blockbuster blood cancer drug Glivec come through.

Fourteen months into his job, which lets him shuttle between the US and India, Hatfield, 66, is attempting something new and ambitious in India: To get its drugs-in-trial thoroughly vetted. Cancer drug P276 is entering phase III trial for radiation mucositis (a condition in head-and-neck cancer where the mouth’s lining is damaged during radiation existing drugs have moderate efficacy). The trial has been set up in consultation with a Harvard University dental group that specialises in this cancer and is certified by another group in the US that specialises in certifying radiation therapy and treatment planning.

“When we get the results, and we hope it’s positive, the data will be of quality that no regulatory authority in the world will have problem accepting. This was my job, to put the stamp of quality within India,” says Hatfield. “This is to leverage the capability in India or how else can you develop a drug at $100 million?”

It’s now apparent that the capital-market-driven investment model doesn’t work well for an industry that has a productivity timeline of 10 years or more. Many believe that the only way to avoid punishment in the capital markets is if the pharma company resets market expectations.

So how does Piramal Healthcare plan to set market expectations now that it is going to burn more on R&D? In the quarter ending March 2012, it posted a loss of Rs 37.32 crore, compared with a profit of Rs 202 crore a year ago. This is owing to R&D spending of Rs 156 crore and reduced income from interest.

Until May 16, when it acquired DRG, analysts speculated healthcare to be a minor play for the company. They feared the company would deploy cash in non-healthcare or high-growth ventures. With the DRG acquisition—which will have $160 million in revenue in 2012—that speculation is put to rest. It adds a new profit generating vertical, and complements the company’s discovery work. Since Piramal Healthcare has had limited exposure to the global NCE marketplace, the information services capabilities of DRG will likely be “synergistic with new aspirations”, says Patel.

“Today DRG serves US, EU and Japan, but now it can expand to all emerging markets and 100 countries that we sell in,” says Piramal.

For its other healthcare businesses, the company has already laid out its five-year growth plan: Contract manufacturing, critical care and over-the-counter segments to grow at 37, 22 and 32 percent, respectively. The first NCE commercialisation is estimated by early 2014. Many will eye the Piramals’ performance in that space. Though, Piramal Healthcare has some leg room. “There’s no pressure on them as nobody is expecting anything,” says an analyst.

Piramal isn’t perturbed by these observations. “People don’t get it,” she says calmly. In 2007, the NCE unit was de-merged because the Indian economy was doing very well and the company expected other investors to join in. But the slowdown hit in 2008. In 2011, it was merged back into the company as the molecules were advancing into clinics for trial and needed more investment.

Additionally—and this is not well articulated yet—the company is open to out-licensing its molecules once it crosses the proof-of-concept stage, that is, phase II or II (a). In case of super specialty molecules, such as those that target cancer, it may go into different markets on its own but for molecules like anti-diabetes ones, that require a big force on the field, it may partner with others.

At 68, says Sharma, he’s working harder than ever. Having lost his wife to cancer last year, getting a cancer molecule to market is “also a personal goal”. Some high-level hires have been made to support him: Rob Armstrong, former vice president for global external research at Eli Lilly and Shashank Rohatagi, former executive director at Daiichi Sankyo, India.

As an entrepreneur, Piramal sees the NCEs as acorns: At least one of which will become a giant oak tree. “Today people may say we are burning cash, but tomorrow if we succeed, this [investment] will look like chicken feed.”

First Published: May 28, 2012, 06:51

Subscribe Now