Naveen Jindal and the New Normal

The intense scrutiny on his dual life hasn't deterred politician-cum-industrialist Naveen Jindal. He is firm on his eventual goal: To become a full-time public servant. But, first, he has to fix his c

Naveen Jindal started taking risks early: More precisely, at the age of six, when his father OP Jindal gifted him a horse on his birthday. He would often fall off the animal, cutting and bruising himself. But the more he rode, the better he felt. “When I ride, nothing else enters my mind. I feel free,” Jindal would say years later.

And he has continued to pick himself up, even in adulthood. An accomplished polo player now, Jindal was captaining his Jindal Steel & Power (JSPL) team in the finals of the Ambassadors Cup in 2012 when his horse suddenly reared up. He fell on his back, suffering two fractures. The injuries didn’t deter him in just a year, he is back in the saddle, as it were, with the polo season warming up for the 2013 season. Whenever he is in the capital, the 43-year-old clocks in at 6.30 am sharp at his farmhouse off the expressway in Noida and rides his favourite horse Sue for a couple of hours.

“Polo is inherently a hazardous and dangerous sport. Anything can happen while I am on the horse. It gives me courage as I am prepared for anything,” Jindal tells Forbes India in his office on the top floor of Jindal Centre at Delhi’s Bhikaji Cama Place. As an afterthought, the chairman of JSPL adds, “If I can do that in sport, then I can do it in life too.”

That fearlessness has shaped Jindal, who juggles two difficult roles: Chairman of the $3.5 billion JSPL and a two-time Member of Parliament (MP) from Kurukshetra in Haryana. Even as a 24-year-old, he fought government norms that barred citizens from flying the national flag round the year. [After a seven-year legal battle, Jindal won the case in the Supreme Court, allowing Indians to hoist the tiranga all 365 days.] A decade later, Jindal became the youngest industrialist to be elected to Lok Sabha, defeating the more favoured Abhay Singh Chautala, son of former Haryana chief minister OP Chautala.

In 2000, as the managing director of JSPL, Jindal spent Rs 1,000 crore to set up a factory in Raigarh to manufacture rails, pitting himself against Steel Authority of India Ltd that has a monopoly in the product category. He is yet to break the public sector behemoth’s stronghold in the segment. Jindal is now trying to use coal gasification technology to run his new steel plant in Angul, Odisha this has not been attempted anywhere else in the world, he says.

These gambles pale in comparison to what Jindal has been preparing for over the last two years. “I spend almost 75 percent of my time on my public responsibilities today... I would like to be full-time in public life in the next two years,” says Jindal, whose aspiration for bigger “responsibilities” in public life is well known. In an interview to a television channel last year, Jindal revealed that if given a chance, he would want to become the chief minister of Haryana. While talking to Forbes India too, he gave enough hints about his wish to be a minister in the Central government.

It is unusual for an active industrialist to dive into the topsy-turvy world of Indian politics. The move is one laden with chance because separating the two worlds, as he has experienced of late, is almost impossible. Politically, his business has made Jindal an “easy target”, and the uncertainty has hurt JSPL’s stock that has nosedived in the past year.

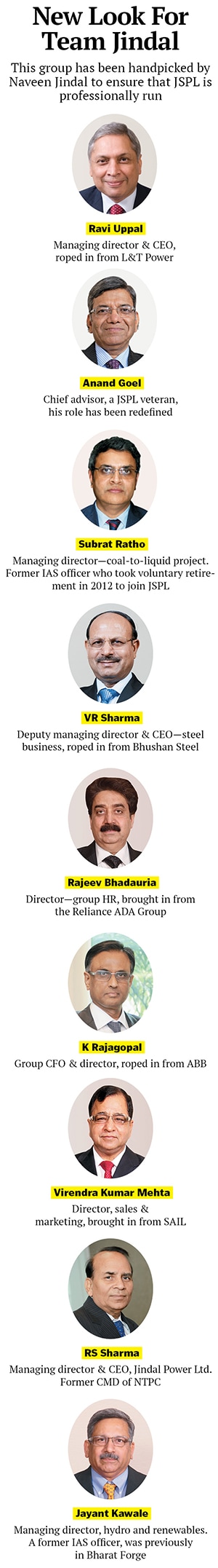

But Jindal isn’t giving up on his attempts to make his political career immune from his responsibilities at JSPL. The steel and power empire is seeing unprecedented changes. Till two years ago, JSPL’s top officials belonged to the OP Jindal days. But, today, a new crop of leadership holds sway at the company. There is a new managing director and chief executive, Ravi Uppal, who joined in October 2012. A former veteran at the multinational, ABB, Uppal headed L&T Power in his last stint. He, in turn, brought in an ex-colleague from ABB, K Rajagopal, as chief financial officer. There have been several other appointments across business segments.

The transition has not been smooth: Some of the JSPL old-timers, including Deputy Managing Director Sushil Maroo and Vice-Chairman Vikrant Gujral, were unhappy with the changes and put in their papers. Jindal had asked Maroo, who was earlier tipped to be the next CEO, to stay on for two more years but he chose to move on to Essar Energy as CEO. Jindal, though, is not overly concerned. “For me to give away control, I needed to hire people who were smarter, more knowledgeable and experienced than me,” he says.

Jindal, at present, functions as chairman. “We want to be a professionally-run organisation, like an institution,” he says. The new management is establishing effective systems and processes and Jindal doesn’t rule out the possibility of becoming a non-executive chairman soon.

Anand Goel, a veteran of 37 years at JSPL, has worked closely with OP Jindal as he now does with the son. He believes that, inevitably, a more formal structure—akin to a trust—will have to be created to handle Jindal’s interests in the company. “Eventually that might have to be done,” says Goel who has stayed on despite rumours that he might also leave after the management shake-up. Earlier JSPL’s joint managing director, Goel is now an advisor to the board.  UNDER THE SCANNER

UNDER THE SCANNER

The significance of these personnel changes cannot be undermined. They were necessitated by the upheaval caused by his political career.

Since 2010, Jindal has found his double life under intense scrutiny. That year, the ministry of environment and forests (MoEF) wrote to the Chhattisgarh government asking it to revoke an approval that had allowed JSPL to build a power plant without the necessity of a clearance [the plant was eventually set up after the company got environment clearance]. Then, last year, India’s Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG), in a report, alleged irregularities by the government in the allocation of coal mines. While most of the Indian metal sector’s blue chip companies were hauled up, it was Jindal who made the headlines. Congress’ main competitor, the BJP, was quick to latch on to the significance. It alleged that Jindal had used his position as a member of the ruling party to benefit his business. A probe by the CBI was eventually announced and Jindal was questioned in September.

To add to the mayhem, Jindal executed an elaborate sting operation on senior officials of Zee Television for alleged extortion of money from his team. The television channel—owned by erstwhile family friend Subhash Chandra who also hails from Hisar— had put Jindal under the scanner for alleged regulatory violations. While many from the industry questioned Jindal’s aggression (“Why should you fight with the media?” says a senior official of a Delhi-based steel company. “He has a knack of being in the news. But now that is backfiring,” says a former JSPL executive), the billionaire thinks otherwise. “It is easy to target me. People keep targeting me but it doesn’t bother me,” he says.

Political whispers are quick to point that for someone who was once touted to be close to the Gandhis, his political ambitions might have been stymied for now. “Many of the younger Congress MPs have become junior ministers in the government. On the other hand, after the CAG reports and after being pulled up by the MoEF, Jindal might not get an opportunity in the present environment,” says a member of Delhi’s political circles. Jindal, though, is unapologetic. “If I run a company efficiently, why shouldn’t I bring that experience in public life? What wrong have I done?” he says. “Yes, I have created wealth, but for all the stakeholders too—the shareholders, employees and the communities around our facilities.”

He has learnt from the school of hurrahs and hard knocks that has been his career so far. First, there were the highs. While the national flag campaign made him a youth icon, as a sportsman, too, Jindal excelled by representing the country in shooting. Politically, he cemented his place after getting re-elected in 2009. Around that time, he was also doing well in business. JSPL became the first private company in India to sell power that reaped billions for the company, its shareholders and Jindal. A report by the Boston Consulting Group in 2010 rated the company as the biggest value creator in the world in the metals and mining sector. In the five years leading to 2010, its stock rose on the BSE, from sub-Rs 30 a share level to nearly touching the Rs 800 mark. It looked like Jindal had seamlessly inherited his father’s mantle as a businessman and as a politician.

That was then. In the last one year though, JSPL’s share price has fallen by nearly 40 percent. Jindal professes confidence in a recovery but that is directly correlated to how JSPL reacts to the management changes. An upturn will help restore investor confidence. Also, a professionally-run JSPL will allow Jindal to devote time and focus on what he loves most—the public life. Much depends on Uppal.

A BLUE CHIP PROFESSIONAL

In Uppal, Jindal just might have got the right man. Consider the pedigree. An alumnus of IIT Delhi, IIM Ahmedabad and Wharton School of Business, Uppal was widely tipped to take over from Larsen & Toubro executive chairman AM Naik at the helm of the infrastructure giant. When that did not happen, he left. At ABB, where he spent 27 years in two stints and was part of the group executive committee, Uppal is known for leading a stupendous growth period in India. From Rs 800 crore in 2000, ABB’s revenues in the country jumped to Rs 7,000 crore within five years under Uppal’s leadership.

At JSPL, Uppal’s task is clear. “We have aspirations to become a global company with operations in India and overseas,” he says. Called Vision 2020, the company wants to touch revenues of Rs 1 lakh crore from the present Rs 20,000 crore. Investments of up to Rs 70,000 crore have been planned to increase capacity in the power and steel businesses, and to garner raw material reserves globally. However, for the vision to become a reality, it was imperative that a family-run business shifted gears and altered its culture. While the process had begun over two years ago with the help of consulting major McKinsey, Uppal has now cemented the change.

“We now have a new governance structure looking at strategic, operational and portfolio issues,” says Uppal. While committees (which report to the board) have been set up to look deeper into specific functions like marketing and risk management, three overall tiers have been established too. At the top is the group executive committee that comprises 12 seniormost executives and is chaired by Jindal. Next is the core management team, which includes 90 top managers of the company—Uppal calls it JSPL’s “brains trust”. Third is the senior management committee of 300 key employees that meets once a year.

JSPL’s operations have also been divided into eight business units, including steelmaking, power, pelletisation and fabrication. Each unit is given a budget for revenue and profit—performance is evaluated against that. CFO Rajagopal, who as ABB’s regional finance head for Asia created a platform where 50 finance officers were reporting to him seamlessly, says: “Now we close the books by the fourth day of the month. This brings in financial discipline. Processes and systems might slow us a bit but, now, it is not individual-dependent.”

Jindal has also hired veterans to head individual businesses. One of them is former NTPC chairman and managing director RS Sharma, who proved a magnet for other professionals to join Jindal’s power business. Using his experience at the country’s largest power producer, Sharma has implemented new systems for vendor and project management which makes monitoring projects possible from any location.

A CRUCIAL PARTNERSHIP

For the new organisational structure to work, Uppal’s rapport with Jindal was critical. Uppal, who hails from an “MNC culture” and clearly prefers to go by systems and processes, understands what is at stake. “This is a huge transformation for the company,” he says. And it is for Jindal too, known to be a details-man. “I have to be pragmatic,” says Uppal. “He (Jindal) can’t change overnight. It is a gradual process. I need to have patience and he needs to show willingness.” Till now, he says, Jindal has been open about listening to him and trying out new management concepts.

Uppal, too, has to adjust to the industrialist’s intense lifestyle. For instance, in the four days prior to the meeting with Forbes India, Jindal spent time at his constituency, flew back to Delhi early next morning and, from there, he went to Mumbai for a business meeting. Back in Delhi by night in his private jet, Jindal then flew to Raigarh early next day to review his plants. He returned to Delhi in the evening to take part in a parliamentary committee meeting. Twenty-four hours later, he was back in Kurukshetra. In between all this, he makes time for polo where, again, his involvement is deep—from buying new horses to discussing breeding technology. “After the morning practice session, we go back home and take rest. But Mr Jindal is in his office or travelling,” says Simran Shergill, a national-level polo player who also looks after Jindal’s interests in the sport.

The passion reflects in Jindal’s personality too. He likes to take quick decisions and depends on his instincts. Interviews for senior posts rarely last beyond 10 minutes. People close to him talk about his restlessness even when he is in his room, often conducting meetings on his feet. His ‘other life’ creeps into his choices too. He travels mostly in big SUVs like other politicians and prefers wearing Nehru jackets to business suits. His public office on South Avenue might be a half-hour drive from Bhikaji Cama, but members of his political team can be seen at Jindal Centre.

While it is still too soon to judge, a successful partnership between Uppal and Jindal could bring back some of JSPL’s glory days on Dalal Street. It will be a tough task as one of the major reasons for the company’s success during the 2005-2010 period was its access to cheap mines that made its power business hugely profitable. With the government looking at the auction route to give away mines, that might not be the case anymore. “The stock’s cheap, but there is no clarity on catalysts and, unlike its peers, it continues to have heavy capex. There are times when the owner’s investment horizon is longer than the minority shareholders’—this is one such example,” says Neelkanth Mishra, research analyst at Credit Suisse, in his report. But as experts say off the record, a bigger concern than debt leverage is the fallout of Jindal’s public life on the business.

But even as business uncertainties persist, Jindal has made the right moves and noises in his political home ground. Even his team at South Avenue is almost as professional as the one that sits at Jindal Centre.

CEMENTING HIS POLITICAL LEGACY

A shy youngster who grew up in the shadow of his three older brothers (Prithviraj, Sajjan and Ratan), Jindal only came of age on a distant political turf in Dallas. He had gone to the University of Texas in 1990 to study business administration. In the first year, he contested and became the vice president of the student body. Next year, he became the president after a tough competition. “I represented the university at several forums, spoke at functions and met people. That gave me confidence,” says Jindal who came back to India to join his father’s election campaign. Years later, when he spoke at the high-brow TED talk, Jindal would share a photo of his “office” at Texas. It is well-organised and elegant, with a huge tricolour hanging on the wall.

The similarities are visible in his South Avenue office. The flag’s presence is obvious. Inside, it is like any other corporate set-up with cubicles where employees are hard at work on their laptops. The office is headed by Vivek Mittal, Jindal’s political secretary and a confidant who had previously worked with his father. “Even while campaigning for babuji (OP Jindal), Naveenji would want to know about everything. His zeal to learn and to try out new things is similar to his father’s,” says Mittal.

His administrative colleagues, handpicked by him, include former consultants at McKinsey and Goldman Sachs, and a graduate of Harvard’s John F Kennedy School of Government. It is an unusual composition for a political team but as Mittal and his colleagues reel out programmes being implemented in Kurukshetra, the intention is clear. In the last national elections, Jindal, claims Mittal, was one of two MPs to have won a majority of votes in each segment of his constituency. Jindal has retained the best minds to ensure a repeat in 2014. It helps that his family’s presence in the state was bolstered by the induction of his mother, Savitri Jindal, a member of the state legislative body, into the cabinet in late October.

JUST A BEGINNING

Of course, the media scrutiny, opposition attacks and the CBI inquiry have been a setback for Jindal. “He was worried those days. But not once has he thought about relinquishing any of his responsibilities,” says wife Shallu Jindal. At his Bhikaji Cama Place office, Jindal seems to have adjusted to the new normal. “I am starting to get used to it,” he says.

He loves the adulation of “his people” when he goes to Kurukshetra. He is also proud of JSPL’s success and gets “a tremendous amount of satisfaction” from running the company. But he has learnt that politics and business don’t mix too well. “I’m sure that it doesn’t help. Otherwise, why aren’t other businessmen getting into politics?” he says. However, not everyone is convinced he hasn’t used position for business gain.

He has some sympathy from within the industry as was evident when his peer Kumar Mangalam Birla was named by the CBI in a coal allocation case. “That is how the system works. You have to meet bureaucrats and ministers because there is disproportionate power in the hands of the people who take decisions,” says the owner of a well-known consultancy firm. For now, Jindal would need to do more to convince others. Perhaps, if he is able to prove his innocence to the CBI, he will gain some of the lost ground. And while he says that “being the chairman of JSPL is just the means to an end, not an end in itself”, the truth is this: Even as he plans an ambitious political career, it will be his role as JSPL promoter that will be in focus. There is no escaping one for the other.

First Published: Nov 19, 2013, 06:26

Subscribe Now