Mytrah's Big Bet On Wind Energy

India has not yet thrown up a wind power utility firm of any scale. Yet serial entrepreneur Ravi Kailas believes he can build 5,000 MW of capacity in five years. Does he know something that others hav

Ever since the first wind turbine was set up in India nearly 20 years ago, no one has looked at wind energy as a serious business. Much of the installed capacity of 15,000 MW in wind was set up to earn tax breaks via an accelerated depreciation scheme offered by the government. As a result, almost 10,000 MW was owned by 1,500 people, translating into an average shareholding of about 7 MW.

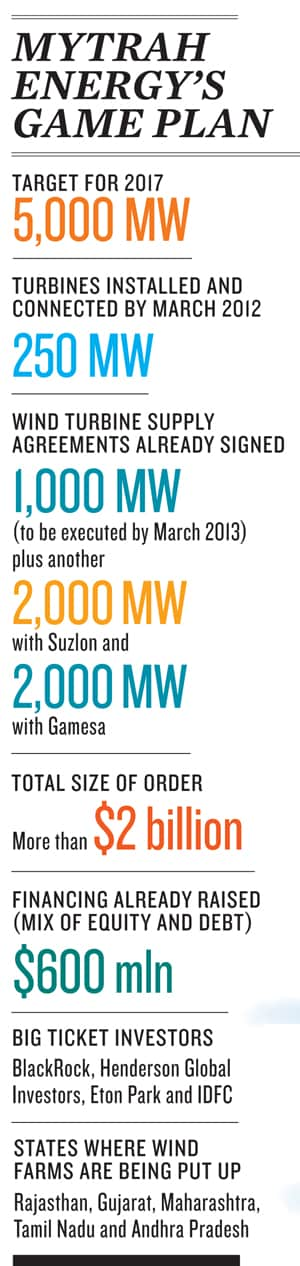

That’s the past. Now stack it against what Ravi Kailas plans to achieve at newbie Mytrah Energy: By 2017, Kailas is betting solely on wind energy to make Mytrah the largest independent power producer (IPP) in the country with a total installed capacity of 5,000 MW. So far, there hasn’t been a single IPP of any scale in the country. Even China Light & Power (CLP), the country’s largest IPP today in the wind business, has an installed operational capacity of about 500 MW built over the last five years.

Now, Kailas is a rank outsider to the wind industry. As a serial entrepreneur, he has built and sold companies in telecom, software and real estate. The 45-year-old Stanford MBA has made his money and fame from Zip Global Network, a telecom services company, which he founded and subsequently sold to Tata Teleservices. Over the last 10 years, he has built and sold two other ventures, Xius Technologies and Altius, a telecom software and real estate financial options company.

So in September 2010, when he announced that Caparo Energy (later renamed as Mytrah Energy) would install wind turbines generating 5,000 MW in the country by 2017 and signed agreements of over $2 billion with Suzlon and Gamesa, two of India’s largest wind turbine manufacturing companies, the entire renewable industry sat up and took notice. Every year, India adds something between 2,500 to 3,000 MW of wind mill capacity on the ground. Suzlon, the largest wind turbine manufacturing company in the country, which also sets up wind farms for its customers, adds about 800 to 1,000 MW every year. “It is a huge number…the largest any company has attempted to do ever in the country,” says Ramesh Kymal, managing director of Gamesa India. Just how could a plain rookie aim to set up 1,000 MW every year over the next five years?

Timing it right

In 2008, Kailas was holidaying in Europe, when the itch to find his next business fix hit him. By his own admission, he wanted to do something in the infrastructure space. “But I could not find any area where I could add some value which existing players were already not doing,” he says. And that’s how he stumbled on wind. What he found in the sector was surprising. India’s wind energy potential is about 80,000 MW 15,000 MW is already installed on the ground. But there was not a single large IPP in the business. “Countries like Spain have several listed wind entities, but in India it is close to nil. Compare this to about 20 listed thermal companies. And in the next 10 years, wind as an industry will add something like 50,000 MW. That’s a mainstream number,” says Kailas.

The entire incentive structure has begun to significantly change in favour of IPPs. Earlier this month, the government scrapped the accelerated depreciation altogether, slashing the rate of depreciation from 80 to 15 percent. Even before that, new generation-based incentives, renewable energy purchase obligations for state utilities under the National Action Plan for Climate Change (NAPCC) and preferential tariff from state utilities for electricity generated from renewable sources had all contributed to an uptick in the generation of wind energy.

With conventional energy sources like thermal and gas becoming more expensive, the state utilities were now willing to make significantly higher tariffs—as much as 40-50 percent more over the last two years in certain states like Delhi and Rajasthan. Since there is no recurring fuel cost, as wind is free, that meant the cost of generating electricity from wind was now at par with a conventional source like coal. “The price at which we are currently producing power at our capital and interest cost is lower than thermal on the margin, which is a phenomenal achievement. This is a unique position for any country to be in,” says Kailas.

For instance, consider Karnataka, where the listed off take price for wind is Rs 3.70 compared to Rs 5 for thermal energy from new coal plants. “There is an incredible, powerful economic construct coming up. So a green energy company that you can build on a utility scale is today actually viable with no subsidies. That is the reason why we believed that wind can be scaled up very, very quickly as opposed to other forms of energy. Today, wind is the cheapest energy in India on the margin,” says Kailas.

Given the new tariff structure, the big challenge before Mytrah was to peg the cost of generating from wind at Rs 3.50 for every unit (kilowatt hour). But that wasn’t the only issue. Several new firms had already expressed their desire to step in. The two most prominent among them are Re New Power, a startup firm founded by Sumant Sinha, former COO of Suzlon with a $200 million funding from Goldman Sachs and Green Infra, another renewable IPP with a mixed portfolio consisting of wind, solar, biomass and hydro, set up by a team led by Shivanand Nimbargi, a senior executive at French power equipment major Alstorm and funded by IDFC Private Equity. So the moot question was whether Mytrah could retain its first-mover advantage and avoid being overrun by the onslaught of competition.

Making the business model work

Kailas is banking on a simple formula to be one step ahead of his rivals. His first task was to raise a mix of low-cost equity and long-term debt ahead of his initial capacity expansion.  So, with help from his nephew, Vikram Kailas, a 31-year-old former banker from Credit Suisse in New York, who is also the finance director, Mytrah achieved listing on the AIM (Alternative Investment Market) in London. “When we went public the investors owned 26 percent of the company. They invested the original $80 million and the total capitalisation of the company was $80 million,” says Kailas. Even the long-term debt was carefully secured for a period of 14 years instead of the usual seven to ensure that the company had enough breathing room on its cash flow situation.

So, with help from his nephew, Vikram Kailas, a 31-year-old former banker from Credit Suisse in New York, who is also the finance director, Mytrah achieved listing on the AIM (Alternative Investment Market) in London. “When we went public the investors owned 26 percent of the company. They invested the original $80 million and the total capitalisation of the company was $80 million,” says Kailas. Even the long-term debt was carefully secured for a period of 14 years instead of the usual seven to ensure that the company had enough breathing room on its cash flow situation.

Besides, the capital raising was made easier, thanks to a strong board, consisting of independent directors like Russel Walls, the chairman of the audit committee of Aviva and Phillip Swatman, the former chairman of Rothschild.

But while most competitors will be able to raise money either in India or abroad, Kailas is banking on scale to drive down the procurement costs (and also gain better payment terms from vendors) and is also hoping to grab large chunks of two key finite resources: Land and talent. His game plan is simple: Build Mytrah at a scale and at a pace which will leave his competitors far behind.

Clearly, Kailas is a man in a hurry. For a man who loves analysing data and wearing well-stitched suits, he’s developed a clinical way to view the wind energy business.

His big priority is to acquire land, build access to the best wind sites, secure the cheapest finance and set up an execution team. “Because we have the scale and we have timed it right, we believe that if we tie up the other finite resources like land and a good execution team, these resources will feed on each other,” says Kailas.

Shortly after its listing in 2010, Mytrah signed a 1,000 MW manufacturing and development contract with Suzlon.

And because it was a large order, Kailas was able to get it at a very competitive pricing structure which he says is not replicable today in the market even for him. “So we are getting to size and scale while people are still trying to enter the business. We will be 1,000 MW by March next year while other people will still be a couple of hundred MW,” he says. This initial head-start would give the team at least a year to learn the ropes of the business.

Kailas says they consciously took a call from day one on the “things that we want to do and things that we did not want to do.”

So turbine manufacturing was ruled out. Mytrah has entered into two large contracts with Suzlon and Gamesa, except that after the initial 1,000 MW order with Suzlon, it plans to build the other wind farms (4, 000 MW) on its own.

That was a smart move. Gamesa, for instance, is customising its turbine for Mytrah, in the sense that they entered India in 2010 and are now setting up several facilities in the country which will allow Mytrah price advantages. “In this industry, capital cost and interest rates are the two largest variables, assuming that wind regime is pretty much constant and same for everybody else. We believe that for the first 3,000 MW, we have already decided our capital cost. And because of our size and pricing also, we are able to get debt on preferential terms,” says Kailas.

Next on the agenda was land. “With real estate there are three tenets: Location, location and location. It is exactly the same with wind. I can’t put a turbine wherever I want to. It has to be at a specific place where there is wind. Having access to it is almost like mining rights,” says Vikram Kailas. India has about 80,000 MW of wind potential, of which 18,000 MW is already built up, plus land for another 20,000 MW is owned by existing players like Suzlon, Enercon and Gamesa, among others.

So Mytrah is joining the race to acquire the balance land with great fervour. Kailas hired Uday Bhaskar Reddy, the vice president of turbine manufacturing company Enercon, to lead the execution strategy. Reddy came in September 2011 and is now the COO at the company. He says that in his 20 years of experience in the wind industry, he hasn’t come across a single player that has attempted to put in 5,000 MW in five years.

Except that the wind turbine manufacturing industry does it—it installs wind mills for its customers, which aggregates to about 1,000 MW in a year.

And that’s where he comes from. “Since we have done this in the past at Enercon, we know the various rules and regulations,” he says.

What Reddy has been able to do is put together a team that has the capability to execute projects. Vikram says it helped that there were no legacy issues at Mytrah. “So, generally in manufacturing companies you have 50 people for land acquisition. Reddy decided that we don’t need 50, but 10 smart people. Another thing is resource mapping. We started in September 2011 but by this March we have 125 wind masts across the country. This is a record for any company. Even Enercon or Suzlon won’t be able to do this in four-five months,” he claims.

On the face of it, while this might sound easy, how would you acquire land without knowing the wind condition there? No such data is publicly available in the country. Almost all of it is held close to their chest by companies who operate in this space. So Mytrah set up its own wind masts to study the wind regime. As you read this, there are more than 125 wind masts in India where Mytrah is collecting wind data. Existing large manufacturers have about 300 masts which they have put up over the last decade. And this was not easy. “The biggest bottleneck when we wanted to do the masts was that there were no vendors. In a matter of three months, Reddy and his team trained the vendors and got them to manufacture those masts in small workshops and ship them to the sites. So this is like almost creating a new supply chain at the back end,” says Vikram Kailas.

That’s not all. Understanding the grid is absolutely critical for an IPP. Because at the end of it what it generates must be sold. And you can’t just pump power in a grid.

Assume Mytrah was to set up a wind farm of 200 MW in Pune. If the grid or the electrical lines around the area did not have the required capacity to absorb the power, it could lead to several technical problems. “If we have to do this we need to collect data from not just Pune, but the whole of Western Maharashtra, which is a huge challenge because it has to be done from the ground level. Access to this data is the biggest challenge because utilities don’t share it so easily. So our guys are going to each and every sub-station to collect the data,” says Reddy.

Kailas says that each of these capabilities in itself will act as an entry barrier to the business because the wind industry has only so many trained people.

“So it is not a case of hitting the ground running. We are taking the time to build this infrastructure ourselves, which I think is not so easily replicable,” says Kailas.

Being a listed company helps. In the last 18 months, Mytrah has raised almost $600 million in equity and debt. Plus it is financed by big ticket investors like BlackRock, Eaton Park, IDFC and Capital International, to name a few.

The company is now working towards raising another $300 million of equity with which it claims it will be fully funded for its 5,000 MW plan. “Once we reach the 1,500 MW mark then the internal cash flows start coming in,” says Vikram.

First Published: Apr 25, 2012, 06:44

Subscribe Now