Mukesh Bansal: The eternal entrepreneur

After building India's biggest online fashion retail brand, Myntra founder Mukesh Bansal is ready for his next innings—and he has a few surprises in store

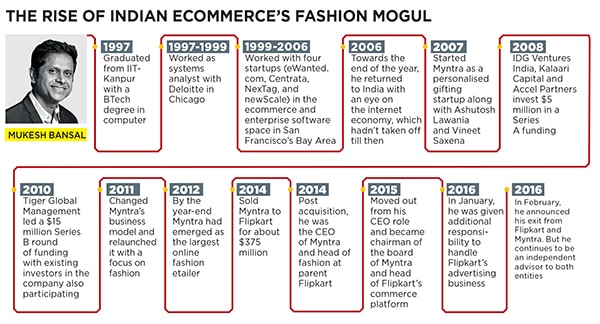

Term it what you will—the irresistibility of enterprise, the novelty of newness—and Mukesh Bansal, 40, the founder and former CEO of Myntra, India’s largest online fashion retailer, will cop to it as the reason for resigning from the Flipkart-Myntra combine on February 11 this year. “I want to feel like an early-stage entrepreneur again and go through the experience and see if I can do it one more time,” he says. But what he will not even remotely allude to as a factor for his decision is conflict. It was an amicable exit, insist all the parties involved—the folks at the ecommerce giant, venture capital firms—rubbishing rumours of a fallout (see box). After all, he is set to stay on as an independent advisor to Myntra and Flipkart.

The reasons notwithstanding, Bansal’s decision to step down as head of the commerce platform and advertising business at Flipkart, and as chairman of Myntra, effective March 31, 2016, was a major shake-up in the company as well as for the industry. After all, post the acquisition of Myntra in May 2014, Bansal had become part of the top leadership team at Flipkart apart from his role at Myntra which continues to retain its own brand identity.

“It has been an intense nine years since I started Myntra. It was a roller-coaster ride with a lot of ups and downs. But I realised that Myntra has a strong leadership team to take the business forward. And that gave me the luxury to think beyond Myntra. It was the desire to do something more in a different space,” Bansal told Forbes India in his first interview since these developments took place. We had met on March 10 at the Myntra office, off Hosur Road in Bengaluru. “I had been thinking about it for a while, but it is only early this year that I decided to go ahead [with the exit].”

And he has already laid the groundwork for his next venture, he says. Far from the world of fashion, Bansal’s new project will be focussed on sports, fitness and health care, with technology inevitably being at the core of the venture. A mixed channel strategy of online-offline may also be considered—a shift from Myntra, which brought mass fashion to our fingertips solely through internet and mobile commerce.

While the business plan is still a work-in-progress, he does share some aspects of the initial concept of the venture with Forbes India. The intention is to create something which will be markedly different from the current crop of players in the health care space, such as Practo, Portea Medical and others. “Currently, there is no integrated platform addressing all the health care needs of an individual. Broadly, we are exploring how to create an integrated platform for personalised end-to-end health care management such as maintaining medical records, diagnostics, prescription, doctor appointments, health insurance, etc, in a cost effective manner.”

He has similar ideas for the sports and fitness aspects as well: A platform that engages all sports lovers—from children and amateur players to professional athletes, including linking them to facilities and providing them with the right guidance and coaching.

The new venture will start as one company launching separate brands for the sports, fitness and health care parts of the business. “It can be spun off into multiple companies later,” says Bansal. Since the project is in its ideation stage, it is too early to talk about the business plan, he adds, but he is clearly bullish about what’s next. Reason: As Bansal points out, sports and fitness together make for a very small market currently, about $10 billion in India this is expected to touch $40 billion in the next five years. Health care, on the other hand, is about a $100-billion market and projected to reach $300 billion in the next five years. India spends only 4 percent of its GDP on health care, with most of the market being left to the unorganised sector. The opportunities are self-evident.

Currently consumed by studying market realities and potential for this next big adventure, Bansal has enlisted a new partner-in-crime —Ankit Nagori, the chief business officer at Flipkart—who also announced his exit from the company in February along with Bansal.

Nagori joins the unnamed business as a co-founder. An IIT-Guwahati graduate in industrial design, Nagori, 30, joined Flipkart in 2010 as a manager and has since been involved in scaling up and launching newer categories such as movies, music and games for India’s largest ecommerce company.

The venture will be based in Bengaluru, and self-funded, reportedly to the tune of $5 million.

Nagori is excited about teaming up with Bansal. Working together for the last two years at Flipkart helped them understand each other better. “In my last stint, I was reporting to him [Bansal] at Flipkart. The focus on quality and talent philosophy in Mukesh caught my attention. He always believed that good businesses are built by good teams. I feel this quality of Mukesh has also helped Flipkart revamp its talent philosophy,” says Nagori.

Bansal explains it like this: “When you are trying to do a difficult task, beyond competence and hard work, I feel loyalty is the most important thing to bind the team together and enable you to do much bigger things.”

And it will prove critical in building their new business, especially at this stage when the ecommerce sector has evolved considerably—greater competition, a different set of challenges—from when Bansal first started out.

The bug bit early

Growing up in Haridwar in Uttar Pradesh, where his father worked for Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited (Bhel), Bansal had a modest middle-class upbringing. He studied at Vidya Mandir Senior Secondary School, and in 1993, left for IIT-Kanpur to do a BTech in computer science. “It was a completely new environment for me. I was surrounded by the best students from the country, and faculty too. The amount of exposure I received from my time there was tremendous,” says Bansal.

The entrepreneurial bug bit him in his early days at IIT. “From my second year onwards, I spent a lot of time in the library and got hooked on to books about entrepreneurship. I read Lee Iacocca, Sam Walton’s Made in America, and about the late Sony founder, Akio Morita. By the third year, I had decided I would build my career around entrepreneurship.”

His plan was to pursue an MBA and start his own venture. But after graduating from IIT in 1997, he got a job with consulting firm Deloitte as a systems analyst, and left for Chicago. “I thought that maybe I would first go to the US, work for some time and then do an MBA and come back and start my own venture.”

Bansal spent almost two years at Deloitte, but couldn’t find his groove in the corporate environment. This was around the time the dotcom boom was in full swing in the San Francisco Bay Area. Drawn to it, in 1999, he quit his job at Deloitte and drove down there—with a friend, and without a job.

While in the Bay Area, Bansal and his friend tried to start a venture of their own, a job portal, but they gave up after persisting with it for a few months. That period did, however, strengthen Bansal’s resolve to work only for early-stage companies.

Between 1999 and 2007, he worked for four early-stage companies in the Bay Area, of which two startups were in the ecommerce space and two in the enterprise software business.

He never ended up doing an MBA. But he was learning at a different kind of school. Those eight years gave him a ringside view to being an entrepreneur, and all the successes and failures of early-stage businesses. While two of the four places he worked at folded (eWanted.com, an online community and auction marketplace, and Centrata, a software company), the other two saw success. NexTag, an online price comparison site, where Bansal was a software engineer, was sold for about $1.3 billion in 2006 newScale, an enterprise software company, was acquired by Cisco in 2011. The company had a modest exit of about $200 million. Bansal was a director (product management) in the company.

It is with a mix of nostalgia and gratitude that Bansal reflects on his time spent in the US. He credits his strong understanding of business fundamentals and building a high performing team to his learning stints with the startups. “Much of the work culture at Myntra was influenced from my experience of working with the startups. I met a lot of interesting people and worked closely with the founders, learning from their differing business styles. Startups go through ups and downs, and I’ve lived the good and bad decisions they took. It was very interesting to see how they handled themselves in difficult times.”

Bansal also witnessed, and imbibed, the culture of equality and transparency at a workplace. He says, “I believe in freedom and autonomy. I never liked hierarchy in an organisation and was biased towards a flat structure. We decided early that we would not have any cabins in the Myntra office. We all work at our workstations.”

Pooja Gupta, former senior vice president and HR head at Myntra, concurs: “I think founding cultures have something very special about them. Mukesh was very clear from the start and only put in place processes that were absolutely required. He wanted to keep it nimble where people could collaborate more easily. Myntra didn’t even have a leave policy when I had joined. Mukesh was all for employees taking all the leave they wanted, as long as they were accountable and productive.” Gupta worked closely with Bansal between 2010 and 2015.

Bansal did, however, face the occasional pangs of self-doubt and the need to keep up with the ‘Joneses’ while abroad. The security of a PSU-sponsored middle-class upbringing was in direct conflict with the risk-loving capitalism of the Bay Area. “When you work for startups, you don’t have a well defined career path. Your growth within the organisation is not well planned. That time, my friends and batchmates from IIT who were working with [the likes of] Microsoft and Oracle were all growing in their careers. I didn’t have a career progression like them.”

The comparisons were fleeting, though. Bansal was deeply invested in his dream of becoming an entrepreneur. “I knew it wouldn’t be an easy task and will be a path filled with risk and uncertainty. There would be many failures, things may or may not work, but it is my conviction that drove me. I am very independent minded.”

Learning at the Myntra school

Whatever Bansal does next will be informed by his Myntra experience—one which began in February 2007, when he moved back to India and started the company. He began by reaching out to potential co-founders, finally partnering with Ashutosh Lawania and Vineet Saxena, his juniors from IIT-Kanpur. Initially seed-funded by Bansal himself, Myntra’s original focus was on personalised gift items such as T-shirts, mugs, pens and caps.

Not many people were convinced about the idea, says Bansal. “The very first investor we met helpfully suggested we shut down and go back to our jobs. She said, ‘All of you have good degrees, why do you want to do this? Stay in the corporate sector, where you will do very well’.” Needless to say, she did not become an investor in Myntra.

Prudently, and expectedly, their beginnings were humble. Operating out of an independent house in Bengaluru’s HSR Layout, Bansal lived above the office on the top floor. It was a small outfit—they played cricket in the evenings, in the lane outside the house. On one occasion, while playing cricket, their first client, a biking club, showed up to collect their order of 40 customised T-shirts. They picked up the T-shirts, but not before joining the Myntra team—then of mere 7-8 people—for some cricket.

The period 2007-10 was one of experimentation for Myntra. They wanted to grow their base, and revenue, so they also ventured into corporate customised gifting. But by 2010, they realised the market for personalised gifting was very small indeed. We could have built a Rs 50 crore business in that space, at best, recalls Bansal. By then the company, and its investors, had started evaluating various alternatives for the Myntra business model.

It was a time of turmoil. The business wasn’t performing to expectations, and there was an increasingly pressing need to move towards a more robust, scalable model. Even his parents didn’t fully understand what he was doing, laughs Bansal, though they were proud of his success. “They were surprised, especially about the personalisation business. They had no clue as to why I was trying to sell T-shirts and mugs.”

By the end of 2010, Bansal had evaluated many categories, and settled on fashion as an alternative business focus. At the time, fashion was about a $50 billion category in India which has now grown to almost $80 billion. The business also offered very good margins and immense scope for growth, given the unorganised nature of the market. It wasn’t an easy decision, though. “To build something painstakingly for four years and then to shut it down—it is a tough transition.”

But by early 2011, Myntra had evolved its business model, and launched its new fashion focus. No one was sure if it would work. Vani Kola, managing director, Kalaari Capital, one of the early investors in the firm, says, “We didn’t have much of an idea about the fashion and lifestyle space. For instance, how does one go and negotiate with global brands such as Puma, Nike, etc, to retail with us, and build the business? It was Mukesh who turned the tide with his absolute clarity. He was very sure this was where the future was.”

Investors saw that and, not surprisingly, according to Bengaluru-based Tracxn, a database for startups and private companies, Myntra (now part of Flipkart) is the most funded company in the country’s online fashion space with a total funding of $159 million raised so far.

In less than a decade of his entrepreneurial journey, Bansal has gained the reputation of being a leader with foresight. His ability to take risks, bold decisions and conviction in what he does is widely acknowledged by peers, investors and competitors alike.

“As an entrepreneur, Mukesh did a great job. He could spot an opportunity in fashion and start a business. Myntra was the first player to create a fashion brand online. That credit should go to him for finding the space and being one of the first few to identify the potential of fashion business online and take action,” says Praveen Sinha, co-founder, Jabong. “He ensured that the competition cannot sleep or lag, even as we kept him on his toes. I think, it was a good sport we had as competitors,” adds Sinha, who exited from New Delhi-based Jabong late last year. “I would have loved to work with him as a collaborator, instead of being competitors that we were. If we have met earlier, that might have even happened.”

Making friends with Flipkart

Though it didn’t happen with Sinha, Bansal did make his competitors his collaborators. In 2014, he met and began interacting with Sachin and Binny Bansal, co-founders of Flipkart. It was around the time Amazon was aggressively marketing itself in India. Bansal worked out the probability of success for his company if Myntra stayed independent vis-à-vis if Myntra and Flipkart were to join hands. Together, the three Bansals were convinced that the combined forces of Myntra and Flipkart would be more effective against a formidable global player.

It helped also that the two companies shared common investors—Accel Partners and Tiger Global Management. This had paved the way for many meetings between the founders from as early as 2008, allowing them to get to know each other reasonably well through social gatherings, events, investor meets and the like.

That set the tone for what was to follow. “It was an aligned viewpoint between both sets of founders,” says Ashutosh Lawania, co-founder, Myntra. “Flipkart would be bringing many things to the table to accelerate Myntra’s growth, and that would also help Flipkart fight competition.” Bansal concurs: “Sachin, Binny and I arrived at the decision. This wasn’t an investor-led acquisition. They believed in both the companies, and in our common vision. We had a strong cultural fit.”

Bansal credits the success of the $375 million deal to their collaborative working style. “For the last one-and-a-half years, we met every week for dinner and discussed business, strategy and would brainstorm on key areas. Our roles were very clearly defined. Everyone had their own strengths.” Sachin was tasked with technology, big picture thinking, and building the business’ long-term vision. Binny took charge of operations and driving quality. Bansal focussed on team building, and fostering a productive, inclusive work culture within the organisation.

For the investors, the synergy between the founders was a key factor in agreeing to the deal. “Mukesh, Sachin and Binny were all talking the same language the day after the deal. In fact, in one board meeting, I jokingly commented that he (Mukesh) was more aligned with Flipkart’s strategy than some of the founders! When we were making changes for 2015, it was Mukesh leading the charge for their commerce platform,” Subrata Mitra of Accel Partners recalls.

It is a testament to the synergistic success of the Bansals that post the Myntra acquisition, Flipkart’s valuation went up five times—in its last round of funding in July 2015, Flipkart had been valued at $15 billion. At present, the Myntra-Flipkart combined entity commands a market share of more than 50 percent of India’s online fashion space.

In May last year, Myntra became the first Indian ecommerce player to opt for an app-only strategy, and discontinued its website. But in February this year, it went back to its mobile website. Multiple media reports indicate that the app-only bet didn’t play out well for Myntra, resulting in a loss in both sales and traffic.

But even his failure was a pointer to his entrepreneurial skills. Sudhir Sethi, founder and chairman of IDG Ventures India Advisors, points out that for a promoter, it is important to broaden his mindset.

“He (Mukesh Bansal) knows his business inside out. He has an understanding of the fashion market, and the internet-mobile market as well. The fact that he took the risk, by going completely mobile, is a step that many entrepreneurs would not have taken.”

Sinha of Jabong agrees: “Mukesh as a leader could take bold decisions. It doesn’t matter if it was a right or wrong move. The decision to go app-only is one such step.”

What was striking to the industry was “Mukesh’s passion for breaking new ground,” says Sethi.

His other passion, we find, is for fitness—of the mind and body.

In the fitness of things

A private person, Bansal doesn’t have a large social network, but a small group of close friends spread across the US, Delhi and Bengaluru. His two younger sisters are also in technology, one with Google in the US, and another at HCL in Noida. A family man, Bansal enjoys spending his time with his wife and two children, a daughter aged 11 and a son aged 6. He requested us to not mention their names—a telling testament of how zealously he guards his family and privacy.

His idea of relaxation is simple: To sit in a corner, curled up with a book. (That habit hasn’t changed since his days at IIT.) “I read a lot, at least one book a week. I love reading about history, science, biographies. My favourite books are Guns, Germs, and Steel by Jared Diamond, A Short History of Nearly Everything by Bill Bryson and Good to Great by Jim Collins.” The rest of his time goes on fitness, spending close to two hours at the gym every day. “I’m up by 5 am and hit the gym by 6. I do everything: Weights, cardio, cross-fit, yoga, and running.” (This also explains the idea for the new venture being based on an intersection of health care, sports and fitness.)

Bansal has also assumed an investor avatar and influenced early-stage entrepreneurs, one of whom is also a friend based in Bengaluru. “He (Bansal) was the first person who told me that instead of working for a company, I should start my own venture,” says Mukesh Singh, founder of ZopNow, an online grocery store. Bansal is an early investor in the startup. So far, he has funded six startups (mostly in the consumer internet space) as an angel investor, including fashion marketplace for women, Voonik, ZopNow and FlipClass, an online marketplace for home tutors. All three ventures are based out of Bengaluru.

His entrepreneurial journey, still not even a decade old, has also transformed him on a personal level. In particular, his fashion sensibilities, says Singh, a batchmate of Bansal’s from IIT-Kanpur. In the context of their shared middle-class upbringing, Bansal’s fashion evolution stands out for Singh. “Mukesh came from fairly modest means in a small town. To come from a place like that, and to be running the country’s largest online fashion business today, is no mean feat. In this whole process, the way he transformed himself is also commendable. There is a huge change in his personality and the way he carries himself. Today, he uses his clothes to make a statement, something the earlier Mukesh I knew couldn’t have done,” says Singh.

Bansal too is cognisant of his renewed relationship with fashion. “Through the Myntra journey, my association with fashion has also evolved. Today I understand fashion more deeply, [I have] my own sense of style. I pay more attention to what I wear. Today, I’m much more confident about experimenting with my fashion choices. Any sartorial statement I make tends towards the classic and understated—I like things clean and crisp.”

Bansal, evidently, isn’t about embracing only what comes easy. He is willing to tough it out, and give a difficult situation a second shot. This was his hallmark, even in college, remembers his classmate Singh. “If I go back to our college days at IIT-Kanpur, he didn’t score too well in his first semester. But in the second semester, he was the department topper,” he points out. Singh extends that to Bansal’s Myntra experience. “Personalised gifting wasn’t doing exceptionally well. The way he pivoted from that model to a company which was selling top retail brands required a lot of understanding about the space and courage to do that. He always made his second attempts count much better than anyone else I know.”

That can only bode well for what’s coming next for Bansal.

First Published: Apr 11, 2016, 06:33

Subscribe Now