How Omkar Cracked The Messy Business of Slum Redevelopment

Omkar Realtors has worked out a business model around usually shunned slum redevelopment projects one based on trust

All she wanted was a different set of tiles to be used in her new house,” remembers Babulal Varma, managing director at Omkar Realtors. “It was as simple as that.”

It was 2003 and Varma had learned his first lesson in Mumbai’s redevelopment business. Now, a decade later, he is the undisputed king of Mumbai’s redevelopment industry, ahead of rivals HDIL and Ackruti.

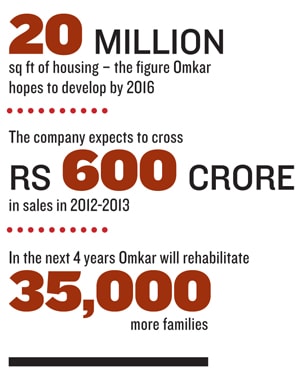

He has already developed 2.5 million square feet in Mumbai and is on track to construct another 20 million by 2016.

He has got to where he has because he listens to the slum dwellers. In 2003, Varma had bought rights to redevelop a chawl (a lower middle class housing set-up with shared verandas and bathrooms).

This was in up-and-coming Parel—an area in central Mumbai. However, soon, he was close to abandoning it. An old lady had refused to vacate.

At a loss for what to do, Varma did what any young entrepreneur would do—act straight from the gut.

He rode up to the chawl in his Hyundai Santro and spent an evening at the lady’s house. They had dinner. He reasoned with her, cajoled her, tried to make her see his point of view.

In the end, it emerged that all she wanted was a different set of tiles to be used in her new house. Varma promised her the tiles and she moved out the next day.

On paper, slum clearance is a great business. Get 70 percent of the residents to agree and a builder gets the rights to build free housing for the group.

In exchange, he receives rights to sell an equivalent amount of residential or commercial space at market rates. With margins upwards of 20 percent, in perennially land-starved Mumbai, this is an opportunity that many should be clamouring for.

Except that no one is. None of the major developers are losing sleep over not being in this business. HDIL and Ackruti, two well-known Mumbai real estate names, had plans to make slum redevelopment a big part of their portfolio.

However, over the years, they’ve realised that this is more trouble than it is worth because of the politics and the red tape.

It’s not that Varma was not aware of the risk. Instead, unlike other developers in this business who often rely on threats and intimidation to deal with resistant residents, his sole aim was to resolve the issue and move on. It is an approach that has made him the king of slum redevelopment in the country’s commercial capital. “Omkar’s slum clearance model is unique in this industry,” says Ramesh Jogani, managing director of IndiaREIT.

He adds that it is the only company that does it so systematically.

What’s surprising is the speed with which the enterprise has grown. Last financial year it clocked in Rs 270 crore in sales.

At present, the company is redeveloping 10 million square feet of real estate in Mumbai. Given the city’s turbo-charged property prices it is a portfolio worth anywhere between Rs 15,000-20,000 crore.

The Initial Journey

Until 2003, Varma was into the contracting business. Originally from Rajasthan, his family had been in the construction business for the last three generations. With a glint in his eye, he’ll tell you how a majority of the havelis across Rajasthan were made by his family.

Varma admits he wasn’t a good student. As a result, he was married off immediately after he graduated and put to work in the family business. By now, the family had moved to Gujarat and made frequent trips to Maharashtra to work in the industrial areas north of Mumbai.

But the scale of their operations frustrated the ambitious Varma. From where he was, he couldn’t see himself becoming a contractor for big, turnkey projects. That was where scale lay.

Fortunately, his frequent visits to Mumbai had given him ample time to understand its real estate market. And he saw an opportunity in the redevelopment business. At that time, Varma was working as a contractor for a steel mill at Wada, north of Mumbai. Its owner Kamal Kishore Gupta had cash to spare. “I was wary of investing it in the steel business where small mills were being edged out by their larger rivals,” Gupta says. The two decided to partner on a Rs 5 crore loan that Gupta made and Omkar was formed. (The two families each have a 50 percent stake in the company.)

When he bought rights to redevelop the chawl in Parel, he worked unlike any other developer. “I have visited each house a dozen times and eaten with all the residents at least once,” he says. If there was a problem I’d make sure it was solved as soon as possible. My number one aim was to complete the project on time.

Government processes were another key area where he realised that developers need to spend a disproportionate amount of time. So, after spending time at the chawl, he made sure he visited Mantralaya, the state government headquarters, everyday. “I would accost people to show me their plans to understand how they got certain permissions,” he says. He would then try and get the same for his projects. In the evenings, he would sit with his architects and work on ways to see how his drawings could be modified to get more space for the apartments he was constructing. On weekends, he would study court judgements and look for legal remedies to his problems.

The Method to the Madness

It was during this time that Varma honed his skills in the redevelopment business. He realised that the reason why most slum redevelopment schemes go off-course is due to the trust deficit between the residents and the developer. According to the law, if 70 percent residents of a particular slum decide to put their houses up for redevelopment the others have no option but to go along. All residents receive a house that is 269 sq.ft. large.

It is the hold-outs that can slow things down for the developer and are often at the receiving end of threats.

It is no secret that real estate companies have been known to use thugs to intimidate residents. Another grouse: Developers often scrimp on housing quality for the erstwhile slum residents.Patiraj Yadav knows the story only too well. He’s been living in Karur, a slum near Malad (northern Mumbai) for the last 42 years. Slum residents originally decided to go with another developer but when there was no activity for over a year he convinced them to go with Omkar after looking at their track record.

At Karur, the company has appointed 10 officers who each have to look after 300 families. They visit each house at least once a week.

First off, the entire slum is mapped by what is known internally as property affairs. Three employees are assigned per 300 families. These employees learn everything about the residents in their area. Any competing property claims are taken care of at this stage. The wing is staffed by people who have worked in consumer-facing businesses. Bank employees and those in sales roles of insurance and telecom companies are preferred. “There really is only one requirement for this job. You must have a lot of patience,” says Varma.

“Our main job is to establish a relationship with them. To get to know their needs and their problems,” says Rahul Bhatia, general manager in the property affairs department that is 150 people strong.

The property affairs team makes sure they meet residents at least once a week. They spend 30-minutes with each family explaining the nuances of the scheme.

On a recent afternoon in Karur slum Bhatia could be seen convincing a family that their children’s needs for schooling near their new houses would be taken care of. He even made an on-the-spot decision to provide a small van for some other children to commute to their present school near the slum.

Another major reason for the trust deficit between builders and tenants has been the shoddy housing constructed for them. Omkar always insists that the same contractor build the for-sale houses and the free houses. To win the trust of the residents, Omkar usually picks a marquee contractor. At Karur, L&T will build both types of housing. Varma makes sure his phone numbers are displayed on the construction sites. Varma insists that free housing has to be completed before the for-sale housing is done.

Detractors of the slum redevelopment scheme have argued that slum residents who move into free housing have a tendency to shift back to the slums and rent out these houses. At times they are also sold, even though there is a cap on selling them for at least 10 years. Most often this happens as residents are not able to afford the maintenance charges for their new apartments. Realising that this is a major issue, Omkar makes fixed deposits of Rs 1 lakh in each resident’s name that pays for the maintenance. This has helped in bringing down the number of families who leave to not more than 10 percent.

Developing the Business

Along the way, Varma has made other deft moves that show he’s always thinking on his feet. To get faster clearances from the Slum Rehabilitation Authority, he’s poached three officers of the authority. As they understand its inner working this move has helped Omkar get clearances faster. He has also acquired an architect firm to get projects designed faster.

As investors have become more confident with the company’s model he has been able to raise private equity money.

RedFort Capital has put in Rs 250 crore in the Karur project. But even now, Varma says, no one will put in money until they see the land cleared.

Parry Singh of Red Fort sees the company as a “manufacturer of land” in Mumbai. With land so scarce in the island city, a company that has a tried and tested clearance model is a definite winner. This year, the company is on track to clock Rs 600 crore in revenue.

If Varma manages to execute these, it could make the company among the top ten players in the country. He has no plans to venture outside Mumbai.

As it is not in the business of buying land and then constructing, Omkar has also had to work out a different cash flow model. Usually developers advertise for houses before they start construction. Once a few are sold, money is collected in tranches and the rest comes in as specific construction targets along the way are completed. In the case of slum redevelopment, over the years, people have put in money for houses that have never been constructed, as the slums could never get cleared. “What this has done is to make it impossible for us to start selling houses until construction has started. This locks up a lot of our money,” says Gupta.

Varma has worked out that the best time to sell the flats is after a fifth of the buildings have been constructed. He usually sells a few flats to investors upfront. They end up paying the full amount in exchange for a lower price. However, maximum houses are sold to buyers who pay in instalments. As a result, once the slum has been cleared the construction usually pays for itself.

Omkar now has a small but committed following of buyers. Take Vibhava Sawant, a lawyer at Khaitan and Company. She invested in the Parel project and says Omkar stood by its time commitment. A couple of years ago she bought another flat that the company is constructing purely on the basis of the experience she had in the first round. “For me sticking to the time commitment is the most important,” she says.

First Published: Apr 18, 2012, 06:12

Subscribe Now