How ISRO Can Join Hands with Private Enterprise

With demand for launches doubling, the space agency wants industry to step up. What will it take for the two sides to pull this off?

A rocket blasting into space doesn’t make news today, such routine are satellite launches and so mature is technology. But, in May, a rocket launch by Californian company SpaceX made news. In fact, it made history as it became the first commercial vehicle to visit the International Space Station (ISS). The launch also signalled an era of private enterprise entering space—US space agency Nasa’s biggest bet in recent times of entrusting small, private companies with big, public responsibilities.

At Antariksh Bhavan, Indian Space Research Organisation’s (Isro) headquarters in Bangalore, Chairman K Radhakrishnan is shuffling his cards for a somewhat similar bet: Of entrusting Indian companies with the task of building rockets and satellites. Isro has a nearly 30-year-old partnership with the Indian industry. Its enduring tango with 400-odd companies has often been cited as a model for the defence sector to emulate.

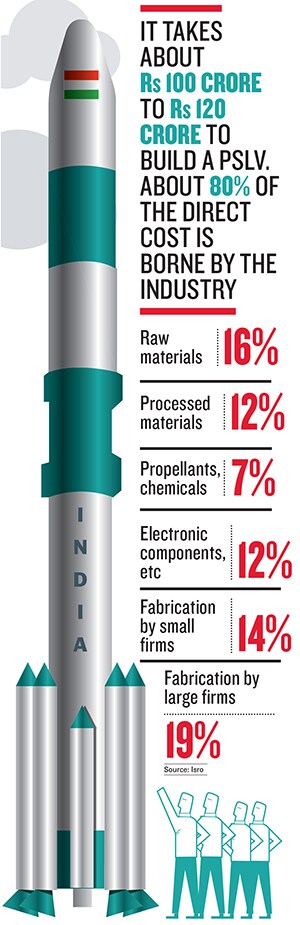

But what Radhakrishnan is now proposing is of a much higher order: It requires the industry to put its skin in the game. He wants the industry to form a consortium and build a Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV)—Isro’s workhorse with 21 consecutive launches—by 2017.

The project may sound over-ambitious, but, in reality, Isro’s time is running out. The 12th Five-Year Plan has sanctioned at least 58 missions in the next five years, as against 29 in the previous five. This boils down to almost one launch a month. The outlay has also doubled from Rs 20,000 crore to Rs 39,750 crore. As Isro can’t double its internal resources, its flight path terminates at the industry.

Globally, this is how most space agencies have built their programmes as well as their local space industry. The US has a tradition of major firms competing for business, with Nasa acting as a managing and contracting organisation. Russia is also catching on, though they have some competing state-run firms too. China is an enigma for most, but experts believe it is taking the Russia route.On its part, Isro has closely worked with the private sector before nearly 60 percent of its budget goes to the industry. The catch is that it has never delegated a fully functional system, say, an engine, to a company. To expect a functional launch vehicle or a satellite from the industry now, Isro will not only have to change its business and organisational model but even its contractual rulebook. That may turn out to be no less challenging than the deep space exploration it has taken up recently. Radhakrishnan says it is possible within the existing government framework. “Five years is a good period in which we can see a launch coming out of the new arrangement I see a lot of enthusiasm [in the industry].”

For the industry, the opportunity is unprecedented: Rs 20,000 crore, i.e. nearly half of the Plan outlay in the domestic market, and the chance to enter the global supply chain of a market that is worth $290 billion today.

It was in the mid ’70s that Isro first began to engage with the industry for supplying components. It increased its ambit in the ’80s when its programmes began to mature. In 1983, Hindustan Aeronautical Limited (HAL) signed an MoU with Isro under which the former dedicated a 54-acre facility for building parts of launch vehicles. That was also the time when Godrej & Boyce kicked off its association with Isro by supplying satellite parts. Over time, they started making liquid engines. One of Isro’s oldest partners is Larsen & Toubro which, in the last 35 years, has worked on all versions of launch vehicles.

Today, the industry does nearly 80 percent of the value addition to PSLV. But Isro maintains a tight control on quality and final integration. It supplies everything from design to materials—even the nuts, bolts and washers. If the industry has to step up, Isro will have to let go of many of its intermediary functions. Companies like L&T and HAL say they are prepared to procure materials, which are often subject to international controls.

A few years ago, Isro made a substantial investment in Mishra Dhatu Nigam (Midhani). A state-owned company in Hyderabad, Midhani makes special purpose metals and alloys. That was a pioneering step that led to our self-reliance, says MV Kotwal, whole-time director and president, heavy engineering, L&T. Now, the private companies can tap Midhani for materials that match Isro’s strict guidelines. “This will free up Isro’s resources. As a company, we are competent to take the responsibility of materials just as we do in nuclear fuel,” Kotwal says. L&T, which makes rocket casings, says it is capable of integrating the complete rocket. “We don’t have a track record with Isro, but we have integrated complex systems for defence. Working with Isro, we’ll do it,” he says.

That’s the general mood in the industry. In fact, it even borders on resentment for not having had the opportunity of doing enough hi-tech work. For instance, Godrej, which now makes engines for various launch vehicles, says it hasn’t built a fully functional system. Its level of participation in the value chain hasn’t progressed much. This applies to L&T too, which is building bigger and more casings, but the nature of work remains the same.

As Isro’s programme matured in the last 10 years, some grudge that it should have worked with its key suppliers to help them ‘graduate’. Even those who’ve come up by holding Isro’s hands are getting more ambitious. Tata Advanced Materials Ltd (TAML), which makes parts for both satellites and rockets using composites, says a lot can be achieved by joint development. “Encourage co-development we are also part of the ecosystem, we also have some ideas,” says TAML Chief Executive Arvind Mathew.

He is particularly motivated because he has been able to leverage TAML’s association with Isro to build its aerospace portfolio and has been able to add clients such as Boeing, Pratt & Whitney, and Goodrich.

Portfolio development is something the Isro chairman wants to emphasise as he invites the industry for formal talks under the CII fold. He held the first talks on September 13 at a space expo in Bangalore. Realistically, space business alone cannot provide the bottom line that the industry expects companies should learn to leverage their work with Isro and build related businesses, says Radhakrishnan.

Until now, the number of satellites and rockets that Isro has launched didn’t make attractive enough volume to lure large companies to make big investments. In comparison, if one looks at the launch log of a commercially successful rocket, say, Ariane-5 of European company Arianespace, it has at least half a dozen launches every year.

In the next five years, this concern will be addressed to some extent as at least 18 PSLV and half-a-dozen GSLV launches are scheduled. But a tricky issue that Isro has to grapple with is the awarding of tender-based contracts. The industry believes that in a technology-intensive and risky business like space, the government cannot follow policies—call for quotations and award the contract to the lowest bidder—which are accepted for other commodities. Proper weightage must be given to technical, manufacturing and financial capabilities, they argue. “You either have a partnership model or you identify a few companies and then work with them for several years,” suggests Kotwal.

For that, Isro needs to come out with a process by which it will identify partners or shortlist companies. “There has to be some protection from government auditors asking why I was picked?” says the chief executive of a company that supplies materials to Isro.

That is a complicated issue. When you try to go outside the tender system, it runs foul of government procedures. Why did you pick company ‘A’ if it was not L1, or the lowest bidder? How do you decide a partner for 15 years when you work in a developmental programme that has no design, no specification and no tender? The Devas controversy of 2010 will be hard to erase from public memory, where Isro, having awarded the contract to a small company for space-based internet delivery technologies, was hauled up for some of these reasons.

Radhakrishnan is aware of these issues, but believes it is possible to resolve it within the system. “That’s how you develop the industry,” he says, emphasising that he’d like the new partnership to be ‘inclusive’ and ‘transparent’ so that even companies who haven’t worked with Isro can participate. “Since we are going into higher responsibilities, everything needs to be written down. Guaranteed off-take being one of them,” he says.

To make this model work, he’ll need commitment from Delhi, which Radhakrishnan hints he has, including that of the Space Commission which he chairs. Having studied the European and American systems, Isro is now pondering how to fund and train manpower, set up facilities and evaluate performance.

These challenges may ring familiar to Isro. In the mid 2000s, some of its large industry partners had proposed building satellites for it. The idea didn’t fly beyond ground evaluation. Industry says the issue of contractual agreements proved a dampener Isro says the industry lacked technological maturity. Over the years, the industry has matured and Isro, even if forced by burgeoning national demand, is willing to make amendments. For all we know, it is already doing so in select cases.

Take, for instance, L-40 strap-on motors that HAL Aerospace makes for Isro. General Manager Jayekar Vedamanickam says the initial cost estimate was lower and HAL invested more for many years.Subsequently, they documented everything and showed it to Isro. Now, the contract has been amended. Documentation of the technology transfer from Isro to its partners is a mammoth challenge for Isro. “It’s often seen that new entrants tend to underestimate the complexity and cost of such projects,” says Vedamanickam.

One such hurdle lies in setting up infrastructure facilities. The industry might be willing to invest, but may demand that it be allowed to use the infrastructure for commercial clients. Godrej, for instance, gets ‘live enquiries’ from Europe, Russia and the US for satellite propulsion systems that it makes for Isro. Can it quote for those customers? No, because the design rights are with Isro. Besides, such commercial orders can be routed only through Antrix Corporation, the commercial wing of Isro that now has an independent chairman. Antrix is ready for such deals, but Isro centres are not free to take up extra assignments, says SM Vaidya, head of precision engineering at Godrej.

Private enterprises are generally better run. Still, the profit motive usually means that they try and milk as much money as they can from state agencies, says David Todd, senior space analyst with advisory firm Ascend in London. Competitive tendering can guard against this but will only work if there are many competing firms. India does not have that. In fact, even Europe, the US, and Russia have had waves of consolidation—there are no longer a large number of competitors. One way out of this problem, says Todd, is what Nasa is now trying out. It’s avoiding cost-plus contracts and is giving milestone contracts to ensure best value. [In cost-plus contracts, the company is reimbursed for its cost of materials along with an added payment milestone contracts pay when pre-defined milestones are reached]

In this context, Radhakrishnan’s consortium approach makes most sense. Examples already exist. Godrej and MTAR have formed a two-party consortium and delivered five key projects for Isro. “If Isro handles its own contracts properly, it will not be milked for funds,” says Todd. Since much expertise that exists in the industry is with Isro, it may have to spin off parts of its own organisation to form expert firms. (One such example is BrahMos, a joint venture between Defence Research and Development Organisation and NPO of Russia.)

One proven way to add volume is to bring regulatory changes, suggests Susmita Mohanty, chief executive of Earth2Orbit, a space consultancy in Mumbai. “India would have to deregulate its telecom market, allowing domestic companies to build, launch, own and operate satellites as well as lease transponders,” she says. Indian companies that will build future communication satellites for Isro should be allowed to build them for international satellite operators and future domestic satellite operators. “Only then will it be lucrative enough for them to participate.”

But tangible gains are not the only ones. As HAL’s Vedamanickam says, a company’s growth or involvement in the consortium will also depend on how “it values its good name and the trust it gets from others because it works for Isro and how working in high-precision engineering has impacted its [product] culture”.

The two sides are carefully weighing risks and gains. Radhakrishnan doesn’t like to use the word ‘risk’. It has a negative connotation, he says. “I’d say the industry has to bear more responsibility.”

The world got a glimpse of that in early October when the SpaceX rocket developed a glitch in freight hauling to the ISS. It managed to deliver cargo but lost a piggyback satellite from another customer. Isro’s two GSLV (a bigger rocket in the making) failures, investigations have proved, were due to manufacturing defect of components—one from Russia, the other from India.

As a government organisation, how far can Isro go? Gazing out of the window of his third floor office, Radhakrishnan takes a long pause. Then says: “As government, you have to develop infrastructure in hi-tech for the country. The industry, on the other hand, looks at the bottom line. Question is: Bottom line of today or bottom line of the future? This is where we differentiate between profit and growth.”

First Published: Nov 20, 2012, 06:45

Subscribe Now