How Ashish Chauhan is Reviving BSE

But it has a long way to go, and faces competition from a third player

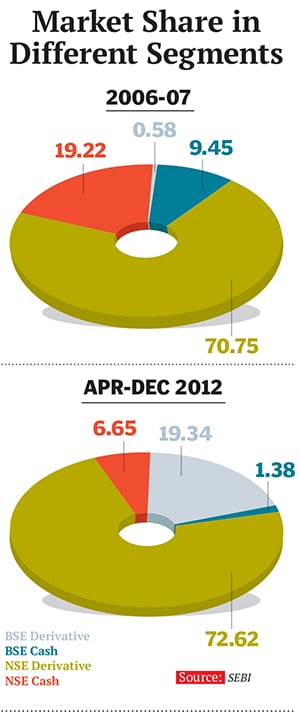

For a stock exchange that began new life in 2007, it’s not doing too badly: A 16 percent market share, up five times in six years a 65 percent share in retail debt and 20 percent in institutional trading and a score of 71 out of 81 offers for share sale put through the exchange.

But for an institution that’s as old as the hills—137 years to be precise—these achievements are underwhelming. Ashishkumar Chauhan, CEO of the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE), believes that the scorecard should be read from 2007, not 1875. He admonishes Forbes India: “You look at the BSE as a stock exchange that is 137 years old. I look at it as a new company that got demutualised only in 2007. We have a new management that is driving this business professionally. And the results are showing.”

Sure, they are.

When Chauhan, 45, joined the exchange five years ago in 2009, BSE was in slide, about to lose the game to rival National Stock Exchange (NSE) in almost all segments of the market. In 2010, BSE had a market share of around 3 percent in both the equities and derivatives space. But since then Chauhan has been a blur of activity. Market share in equity and derivatives is up to 16 percent the trading technology is being given an adrenaline shot through a tie-up with Deutsche Borse, which will enable the exchange to process 500,000 orders every second (NSE can currently manage 160,000) and then there’s a tie-up with Standard and Poors Dow Jones (SPDJ) Indices to elevate the Sensex brand. The 30-share BSE Sensex is now the S&P Sensex, giving it an international image boost.

Despite its 137 years, Chauhan’s BSE is beginning to develop the get-up-and-go spirit. “The BSE has a lot of rigour and energy to create new products,” says Koel Ghosh, who looks after business development at the new BSE-SPDJ index company based in Mumbai. The tie-up with S&P is particularly sweet for BSE, because the former’s first alliance was with NSE. The break-up of that marriage allowed Chauhan to poach talent from NSE.

That includes Ghosh, a SPDJ employee, but Chauhan himself is a product of NSE’s innovative years. He was part of the five-person startup team at NSE in 1993, the other four being Ravi Narain, Chitra Ramakrishna (the new managing director), Raghavan Putran and K Kumar. This team largely created the NSE under the tutelage of the late RH Patil of the IDBI.

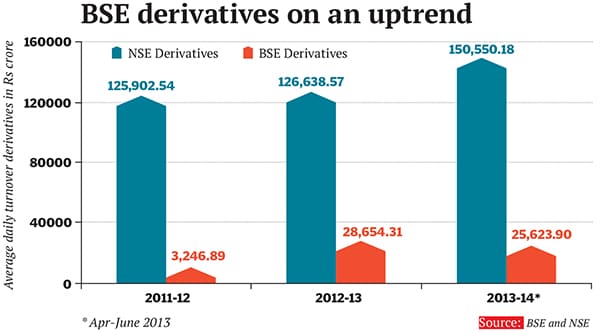

Chauhan’s key achievement at NSE was the launch of the derivatives segment in 2001—it turned out to be a roaring success. He now wants to do an encore at BSE, and has managed to make significant headway. From zero, BSE’s market share in derivatives is 20 percent today. In index options, Chauhan has a 25 percent slice of the action. Taking equity and derivatives together, the market share is 18 percent.

“Ashish Chauhan is the best thing that has happened to the BSE after MR Mayya (former executive director). He is in tune with the big picture and has his ears to the ground. He really understands what market participants want in their product offerings. He has already gained market share in derivatives and other products,” says Deena Mehta, CEO of Asit C Mehta Investment Intermediaries. She was the first woman president of BSE back in 2001.

Chauhan’s strategy can be summed up in two words: Widen and deepen. In the stock market, the key to success is trading depth, or volumes. Volumes depend on liquidity—which, in turn, means making transactions cheaper. Chauhan chased volumes by dropping prices.To attract volumes, Chauhan offered a Liquidity Enhancement Incentive Programme (LEIP) under which BSE charged only Rs 50 for option premium trades worth Rs 1 crore. Compare this with NSE’s Rs 5,000 and MCX’s Rs 2,500, and you know why Chauhan expended Rs 95 crore in 2012-13 to drum up business. But it wasn’t a LEIP in the dark, as volumes soared.

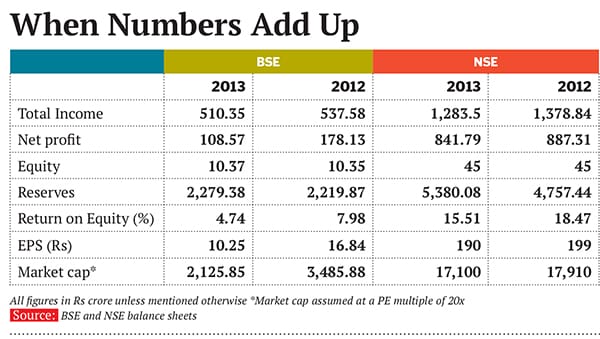

The quest for market share brought a dent in the bottom line. And this is where BSE’s metrics pale before NSE’s. In terms of top line, NSE is twice as big as BSE at Rs 1,283 crore in net profits, NSE had a padded bottom eight times as large at Rs 841 crore (see table, page 56). Where the comparison really hurts is return on investment (ROI)—the ultimate measure of the success of a business. While NSE has managed to maintain ROI at a super-healthy 16 percent, the same number for BSE is a dismal 4.74 percent.

It’s early days yet, and Chauhan feels he needs time to spruce up on profitability. He points to his zero to 20 percent share in derivatives growth as proof that his business growth strategy is working.

But that’s the depth part he is also trying to widen BSE’s reach by going for the small fish. As a market veteran, Chauhan knows in his heart of hearts that he cannot beat NSE at its own game. So he is trying for new game in the small and medium enterprises (SME) sector and mutual funds. He wants to encourage more SMEs to list on BSE, and mutual funds to sell units through the market. Another window he has opened is the offer for sale—a device used by promoters to sell smaller lots of shares without an IPO to comply with market regulator Sebi’s minimum public shareholding norms.Chauhan is not without his sceptics. “The Indian markets still have a long way to go. There is no liquidity beyond the top 200 stocks. Even SME business will not really help because the markets are becoming global in nature. Since the business is driven through technology, we need to understand how it will be conducted into the future,” says Nikhil Vora, managing director and research head at IDFC Securities.

As the stock exchange business changes, Chauhan is looking for new revenue streams. Apart from transaction fees, exchanges also rely on the sale of market data, listing fees and membership charges. Chauhan feels that it made sense to rely on transaction fees in 1993. But not anymore, since high transaction fees can dent volumes and kill the exchange. He is, therefore, looking for other lines of revenue—including data sales and carrying advertisements on the BSE website.

“Trading volumes are important but, more importantly, the exchange wants to get into a line of products where it can get an early mover advantage over the other stock exchanges,” says Chauhan.

Where It All Began

A mechanical engineer from IIT, Powai, and alumnus of IIM Calcutta, Chauhan was recruited from the campus by the Industrial Development Bank of India (now IDBI Bank) in 1991.

His designation was that of industrial finance officer—a business that was soon to hit the skids, as project finance was heading for a tailspin. His break came in 1993, when the government’s disenchantment with the unreformed BSE led it to propose a rival stock exchange in the National Stock Exchange.

In 1993, Chauhan, Ravi Narain, Chitra Ramakrisha, K Kumar and Raghavan Putran were given the job of creating NSE from scratch. Chauhan himself was involved in creating the trading infrastructure at NSE.

Two years later, Chauhan was successful in bringing exchange-traded derivatives. Along with Ajay Shah and Susan Thomas, he looked at NSE’s risk management system. The team created a metric to measure liquidity in stocks—called impact cost—which is now standard practice.

The rest, as they say, is history, and by 1998 NSE’s success made everyone cocky, Chauhan included. A story is told that when a marketing team from a leading mainstream daily went to Chauhan asking him to advertise on their new website, Chauhan sent them packing. He told them that his website had 100 times more traffic and he would be happy to have them advertise on the NSE website.

Chauhan is now in a position to check if his boast of that time will work with advertisers. “I was young at that time. Now I pretty much have the same view but will communicate the same in a better way,” he says.

In 2000, Chauhan left NSE to start a company called exchangenext.com, a business-to-business dotcom venture. The idea was to create something for the manufacturing sector, especially petrochemicals, steel and cement. The venture was financed by the Reliance group. But when dotcoms crashed, the venture started to bleed. The entire team then got shifted to Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Infocomm.

In 2004, Chauhan became the chief information officer (CIO) of Reliance Infocomm. After the Ambani brothers split, he stayed on with Mukesh Ambani and was made the group CIO in 2005. The job was to organise Reliance’s IT business under one roof.

In 2009 he decided to move out of the Reliance group. His wife, who was a majority stakeholder in an IT company called Marketplace Technologies that offered back-office solutions to brokers, sold out to BSE. One of the conditions of the sale was that Chauhan would work with the stock exchange for at least a year. The then CEO of the exchange, Madhu Kannan, was very keen to have Chauhan on board and he joined BSE as deputy CEO in September 2009.

Kannan himself left in 2010, leaving Chauhan in charge. Having recently demutualised in 2007, the exchange had low business volumes but two great assets: The Sensex index and a distribution network. What it lacked was products for the market. The technology too was outdated.

The first thing Chauhan did was spruce up the management. He appointed Nayan Mehta (poached from NSE) as CFO of the exchange, Kersi Tavadia (poached from Etrade investsmart) as CIO, Sounder Rajan (also from NSE) as clearing and settlement in charge, and Shankar Jadhav (from Reliance) to handle strategy.  The Next Big Bet

The Next Big Bet

The stock exchange business is no longer what it once was—about trading floors and shouting brokers. It is more about software and a network of computers that collects data from thousands of terminals, and redistributes it. But with transaction costs falling due to competition and technology, the key to profitability is high volumes. In India, only 2 percent of retail investors trade, and many market mavens believe it could rise to 15 to 20 percent, bringing in good business for exchanges. It was on this premise that MCX put forward its value proposition to get smaller companies to trade on the exchange. Since the big institutions do not trade much in small companies, the latter should attract trading volumes from the retail segment.

Or so goes the logic. But reality has proved quite different. Almost 98 percent of the Indian market is ruled by institutional investors with retail investors opting for mutual funds. There is little chance that this trend will reverse anytime soon.

Chauhan believes that the retail factor cannot be written off. “We need to be ready for any eventuality. I understand that the markets are getting institutionalised but the fact is that retail is hardly 2 percent of the Indian markets. This has to grow. So I need to be ready with more products whichever way the market goes.”

Trend towards consolidation

While most people are willing to give the BSE a chance, a larger trend seen globally is one of shrinking margins and greater consolidation. In 2006, the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), the world’s largest, acquired Euronext, the fifth largest, for $12.12 billion. In 2008, CME, the largest commodities exchange, acquired Nymex, an energy exchange, for $7.6 billion. As global consolidation gathers pace, can India support three stock exchanges—NSE, BSE and the newly-started MCX-SX?

Many people do not rule out consolidation in the Indian markets but that will take some time.

“The competition is very tough but NSE will maintain its leadership position. The real competition will take place when MCX-SX becomes a formidable player to compete with BSE. In my view, MCX has a better chance because it is a hungry exchange, while BSE is very rigid,” says an analyst who has been tracking the stock exchange space for a long time.

India could also resist the consolidation trend since volumes have nowhere to go but up as the economy grows. Looking at these prospects, the exchanges themselves are planning to list to unlock value for their stakeholders.

NYSE has a market capitalisation of $10 billion (Rs 60,000 crore at current exchange rates) and trades at a price-earnings (P/E) multiple of 27. Compare that to NSE, which will be valued at Rs 17,100 crore on a P/E multiple of 20. At the same P/E, BSE would be valued at a mere Rs 2,125 crore.

That gap is what Chauhan needs to close. But Chauhan knows the media is not convinced BSE is a winner. “We are taking the right steps. We need some more time. But you guys will write us off even if we are showing you the numbers”.

Once the numbers show up, no one can deny him his due. For now, he hasn’t got the numbers to wow the world. But, to say the least, he has brought BSE back into the game. That’s no mean achievement for an exchange that was a stretcher case just a few years ago.

First Published: Jul 19, 2013, 07:08

Subscribe Now