Grofers vs BigBasket: Tale of two strategies

Going deep versus going wide: Which will trump the other as online grocers BigBasket and Grofers battle to corner market share?

Grofers has pulled the plug on organic products and perishables which have a low shelf life

Grofers has pulled the plug on organic products and perishables which have a low shelf life

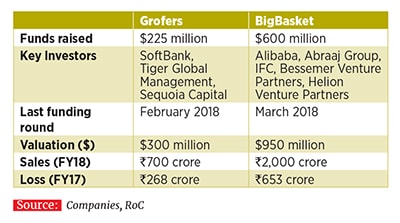

Both have burnt through millions of dollars for a podium finish in online grocery. Both are backed by moneybags, SoftBank and Alibaba, whose interests are perceived to be aligned. But, BigBasket and Grofers, the two largest homegrown online grocery stores, have adopted divergent strategies to survive and thrive.

BigBasket, the Alibaba-backed market leader with approximately ₹2,000 crore in sales in FY18, lives by the holy grail of grocery business—spoil consumers with multiple choices under one roof. Grofers, funded by SoftBank and Tiger Global Management, has instead chosen to champion a select few categories to hold fort against BigBasket and an impending incursion from the likes of Amazon and Flipkart.

Opinions are somewhat skewed in favour of BigBasket’s methods. Says Ankur Bisen, associate vice president of retail and consumer product at Technopak Advisors, a consultancy firm, “One cannot pick and choose categories in grocery retail. One has to complete the offering and that principle does not change. For a consumer, it is a mixed basket, where all categories will have a 10-15 percent share.”

Grofers, however, has defied conventional wisdom. The firm clocked ₹700 crore in sales in FY18, up from ₹250 crore the year before and is on track to exit FY19 with ₹2,500-3,000 crore in sales, says co-founder and chief executive Albinder Dhindsa. Monthly cash burn, however, remains constant since mid-2016, at approximately ₹15-18 crore. “If you pierce a stack of papers, you need a very sharp tip. The idea is to have a sharp tip to penetrate the market. We are not in the width game but the depth game,” says Dhindsa. An employee scans a package at a BigBasket warehouse on the outskirts of Mumbai

An employee scans a package at a BigBasket warehouse on the outskirts of Mumbai

Image: Danish Siddiqui / Reuters

Over the last two years, Grofers has come to identify its sweet spot—the middle and lower middle income group, whom Dhindsa calls the ‘motorcycle families’—and is assiduously working towards aligning its offerings to the target audience. This would mean pulling the plug on a non-core category such as electronics, the relatively expensive organic products, and gourmet food and perishables such as fruits and vegetables, which are considered tough to master largely because of supply chain constraints and low shelf life. Also, aggressive marketing spends to the tune of ₹3-7 crore a month have given way to initiatives like floating a loyalty programme to cultivate a dedicated audience.

A business-to-business (B2B) vertical, where Grofers catered to institutions such as hotels and restaurants among others, have been shuttered as well. Dhindsa says the Grofers way of serving consumers is about offering attractive price points through its in-house brands. Consequently, Grofers has lined up an array of private brands, which fetch higher margins than third-party brands. They account for about 30 percent of Grofers’ sales.

BigBasket, which according to co-founder and chief executive Hari Menon is on track to exit the current fiscal with ₹4,000 crore in gross sales, is at the opposite end of the spectrum. The firm remains steadfast at introducing new categories and services to capture the market. It dabbles in everything, from staples, meat and fresh produce like fruits and vegetables to FMCG and home appliances among others, with a mix of in-house and third-party brands. In-house brands account for about 36 percent of its sales, says Menon. According to two people aware of the developments, Grofers is in talks with new investors to raise at least $100 million in fresh funds. It is said that it even held talks with Alibaba

According to two people aware of the developments, Grofers is in talks with new investors to raise at least $100 million in fresh funds. It is said that it even held talks with Alibaba

Flush with funds, BigBasket has now set its sights on expanding its stronghold over categories like meat and beauty. It already stocks meat, buying it from large vendors, but the plan is to go deeper into the supply chain and source directly from the animal breeder, similar to its fresh supply playbook where it sources about 80 percent of fruits and vegetables directly from the farmers. BigBasket also runs a B2B business where it sells private brands to commercial establishments. Besides, it distributes its private brands to approximately 5,000 brick-and-mortar grocery stores across the country.

Next up are subscription-based diapers and milk delivery business and unmanned kiosks at commercial and large residential complexes across the country. The firm is reportedly in talks to acquire a stake in Fireside Ventures-backed Kwik24, which operates smart vending machines and Rain Can, a milk delivery startup. Menon declined to comment, but maintains that offering a whole lot of services to consumers is the need of the hour.

“From a consumer standpoint, they need range and a single place where they get as much as they need,” he said in a phone interview. For instance, fresh produce, a category discarded by Grofers, accounts for about one-fifth of BigBasket’s revenue.

For Grofers, however, 2015 was a watershed year that forms the cornerstone of its strategy of “going deep, not wide”. “This is a lesson we learnt in 2015, that pick your battle, and we picked it well,” says Dhindsa.That year, the firm snared $165 million from Sequoia Capital, Tiger Global Management and SoftBank to build a hyperlocal grocery delivery startup. In November 2015, when it raised its largest ever tranche of $120 million, Grofers was valued at approximately $400 million. In FY16, Grofers posted losses of ₹225 crore on revenues of ₹8 crore, emblematic of a funding bubble.

Like many of its peers who had embarked on an aggressive expansion drive and customer acquisition spree, but later retreated once the funding tide started receding in early 2016, Grofers too shrunk operations to conserve cash. In January 2016, the firm stopped operations in nine cities. A few months later, it trimmed its workforce by a tenth and revoked close to 70 job offers to potential recruits from marquee educational institutes. A course correction ensued. At the core of it was discarding its asset-light hyperlocal sourcing in favour of an inventory-led model.

Today, the firm has recovered and the investors are back. In February, nearly two years after it last raised money, Grofers mopped up $60 million from existing backers SoftBank and Tiger Global Management, albeit at an approximately 30 percent slump in valuation. According to two people aware of the developments, Grofers is in talks with new investors to raise at least $100 million in fresh funds. Among others, it also held talks with Alibaba, the people cited above said. Dhindsa declines to comment on the specifics of the fund raise, but says investors are now keen on bankrolling grocery startups.

“The narrative of the investors has changed significantly from the last year on grocery. They thought the horizontals (Flipkart and Amazon) will spoil the show, but, they couldn’t do much. That sentiment drives valuation, not always the state of the business,” says Dhindsa. “Also, investors thought we were overvalued in 2015, so there was a correction due and that happened.”To be sure, while Grofers and BigBakset continue to surge in their own ways, an imminent threat from Amazon and Flipkart, now a Walmart subsidiary, looms large. Both companies have professed their intent to go all out on online grocery, which Crisil estimates to become a ₹10,000 segment by 2020 from approximately ₹2,500 crore in 2017. For instance, Amazon last month teamed up with private equity fund Samara Capital to buy out Aditya Birla Group-owned More for $580 million. The Seattle-headquartered ecommerce behemoth is reportedly in talks to pick up a stake in RP-Sanjiv Goenka Group-owned Spencers Retail as well as Kishore Biyani’s Future Group-owned Future Retail.

However, grocery sales on these marketplaces haven’t shot through the roof, yet. But the anticipation of an onslaught from the marketplaces has triggered talks of a consolidation in online grocery, which has anyway seen startups such as Localbanya, PepperTap and ZopNow among others fall by the wayside. According to the two people cited above, Grofers and BigBasket have also contemplated a merger, though talks are at an early stage. The idea is to forge a single entity, backed by Alibaba and SoftBank, which could counter the advances of Amazon and Flipkart.

But, a turnaround at Grofers also implies that it may eventually succeed in raising funds independently. “Mergers happen when one company fails to raise any significant amount of money and tries to find a home for itself. Grofers is not in that kind of a position today,” says a person aware of the discussions.

Industry observes believe it is too early for either BigBasket or Grofers to press the panic button.

“To build a grocery business, the supply chain needs investment. To that extent, the horizontals (Flipkart and Amazon) do not have an advantage other than the huge customer base to which they can sell grocery. However, Amazon and Flipkart are deep pocketed and may create some turbulence by giving offers, but it has to be well-balanced with good products, else sooner or later customers will return to the go-to stores,” says Aakash Goel, partner at Trifecta Capital Advisors.

Avers BigBasket’s Menon, “After all, we do it for a living.”

First Published: Oct 26, 2018, 12:34

Subscribe Now