Ex-Maruti Man Jagdish Khattar Aims High with Carnation

Will Jagdish Khattar's new game plan win against the neighbourhood garage?

As the managing director of Maruti Udyog, Jagdish Khattar had proved his detractors wrong, and how.

An Indian Administrative Services officer, he had joined Maruti in 1993, and had become its managing director in 1999. Between 2000 and 2008, the company’s revenues more than doubled—Rs 9,000 crore to about Rs 22,000 crore—while profits rose more than five times, from Rs 330 crore to Rs 1,730 crore. Industry experts predicted that Maruti would have a tough time against global majors like General Motors, Ford, Fiat and Honda. But Khattar proved them wrong.

It is yet to be seen if Khattar can prove his detractors wrong, once again, with his four-and-a-half-year-old venture Carnation.

On January 3, 2008, 66-year-old Khattar turned entrepreneur, and started Carnation Auto. Although the initial idea was that of a multi-brand car showroom, over the past four years, Carnation’s business proposition has undergone multiple changes. And Khattar remains far from success: With a turnover of just over Rs 130 crore, the company is yet to make any profit. In fact, with a turnover of about Rs 81 crore in FY2011, it recorded a loss of Rs 52 crore.

A critical cog in Khattar’s efforts to make Carnation a success is the speed at which he can decide on a clear business proposition for it. From being a multi-brand dealership for new cars, it got into the business of multi-brand car service. Now, Carnation has ventured into selling used cars, and wants to sell accessories and insurance as well.

But what exactly does Khattar want Carnation to be?

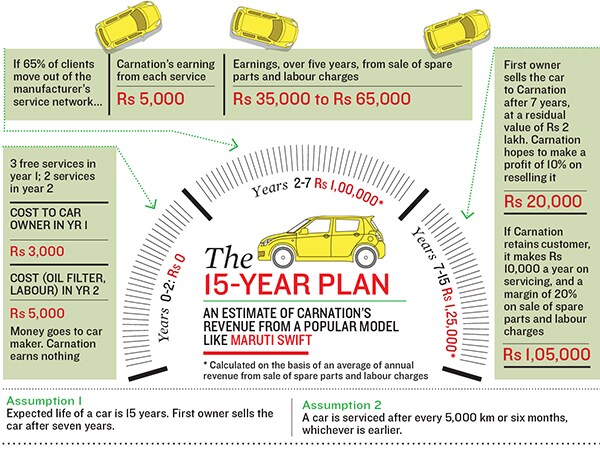

From his recent moves, it can be said that he wants Carnation to deal in and service cars that are no longer covered by the manufacturer’s warranty. He wants a share of every rupee a car owner spends when his car is no longer new.

While success is still not guaranteed, this business plan gives Carnation a better shot at it.

Under One Roof

At present, someone looking to buy a used car goes to Mahindra First Choice or Maruti True Value, or a local player like Popular Cars or Sah & Sanghi in Mumbai and TS Mahalingam in Chennai. For servicing the car, owners look to neighbourhood garages, whose rates are lower than the authorised outlets of manufacturers. And when he wants to sell his car, he either goes back to a used car dealer, or sells it on his own.

All these are usually unrelated transactions.

Khattar is aiming to aggregate all these needs of a car owner under one brand. But what is the size of the market that he is looking at?

Say, for instance, if a million new cars were sold in India in 2010, by 2012 none of them would be covered by the manufacturers’ warranty. Of these, 65 percent (6.5 lakh cars) would not return to the manufacturer’s authorised service centres, and enter the unorganised market for services and repairs. Khattar wants at least 10 percent of this market.

PE investors Premji Invest and IFC Ventures had invested Rs 104 crore in Carnation in 2008, and Gaja Capital Partners invested Rs 84 crore in 2012.

Khattar’s current business model increases the chances of cross-selling services, and reduces competition with car manufacturers. Globally, car companies are not comfortable with the idea of a multi-brand showroom.

In a move favouring consumers, the European Union passed a legislation called the ‘block exemption’ rule, allowing multi-brand car sales and services within the EU in 2003.

But manufacturers remain averse to the idea for two reasons: Complexities arising out of allowing various brands—including rivals—to be sold in the same showroom and the fact that they do not make huge margins on sales.

A far greater source of profit is after-sales services. A 2003 McKinsey report found that net profits from spare parts sales, service contracts, financing and insurance subsidise new car sales after-sales business accounts for almost 60 percent of gross profits.

Inch Deep, Mile Wide

Now that Khattar has moved away from his original idea of a multi-brand dealership for new cars—and is therefore not in direct competition with manufacturers—car companies might be a little more accommodating.

A walk around Carnation’s workshop in Kurla, Mumbai, puts this into perspective: An Audi A4 is being painted in the paint booth a Mahindra Xylo is undergoing serious repairs after having met with an accident a Fiat Premier Padmini (more than 20 years old) is undergoing complete restoration three Honda vehicles are in queue, along with a Mitusbishi Cedia (whose parts are not stocked even by authorised dealers) and about 15 other vehicles from different manufacturers.

In India, once a new car’s warranty expires (usually after two years of purchase), 65 percent to 70 percent car owners do not return to the manufacturer’s authorised service centres, and opt for the neighbourhood garage instead.

While these garages are cheaper, closer to home and offer personalised services, the quality of service is based on trust, and the genuineness of spare parts and the capabilities of the mechanics remain uncertain.

“The opportunity is huge. In developed markets such as Europe or the US, one third [of the 65 percent quoted earlier] of this market is with organised players. In India, organised players don’t constitute even 1 percent of it. It is a question of how much hunger you have and how much you can execute,” says Khattar.

His approach is complex, and requires substantial trained manpower. There are about 15 car manufacturers in India, each having sold at least five models in the past 10 years. A good multi-brand service centre outlet would need access to parts for about 65 vehicles, and at least eight trained mechanics. On any given day, a customer can walk in with any car and refusing him is not an option.

The Indian automotive market is dominated by three manufacturers—Maruti Suzuki, Hyundai and Tata Motors—who make up for almost 60 percent of sales. “As of today, 70 percent of our volumes come from these three manufacturers. It is with the other 30 percent that issues crop up,” says Felix Louis, vice-president, operations.

The issues that Louis refers to are difficulties in procuring genuine parts (which are also very expensive), and the cost and effort of training mechanics.

Growing His Own Food

But banking on just services and repairs is not going to increase volumes and revenues fast enough as publicity would take time. Khattar believes that one way of boosting demand for his after-sales services and repairs is by selling used cars which would, then, feed back into the service network. So, over the past year and a half, he has set up 17 used car facilities in Mumbai, Delhi, Punjab and Noida, among others. The idea is to build an eco-system where every used car facility feeds the workshop.

For this, the man who swore by Japanese paper work at Maruti Udyog has now taken to the world wide web. “On one hand, you have websites—like Carwale—that only list used cars. On the other hand, you have unorganised shops. What we are doing is marrying our brick-and-mortar facility to the Carnation website,” says Khattar.

“This ties in seamlessly with our business model. And we now offer a 1-year warranty to those who buy used cars,” says Louis.

Khattar’s model, however, is not universally accepted. R Srivatchan, president of TVS Automobile Solutions, or MyTVS, has a different approach.

MyTVS has a network of 30 multi-brand service outlets in South India. Srivatchan highlights the importance of refusing a customer. “Because sometimes you can easily make promises you can’t keep. We have to be humble about it,” he says. So, a Ford or a BMW is a no-go. “Some of the Ford dealerships themselves can’t repair Ford vehicles. We have a list of 45 things that we can do in a vehicle. If a customer walks in with something that is outside our map, then we politely turn him away,” he says.

Scaling up

Both Carnation and MyTVS claim that their costs are lower than the authorised service centres of any carmaker. But that’s not who they are up against their competition is the neighbourhood garage.

There are two grounds on which an organised services and repair set-up can compete with the neighbourhood garage: Genuine parts, and a superior experience.

“I don’t know if we are cheaper than roadside mechanics, but I can definitely say we provide genuine parts and good service,” says the manager of Carnation’s Kurla facility. Srivatchan of MyTVS has a more evolved argument: “The value proposition for us is the service, set-up and experience of a dealer as opposed to a roadside garage.”

The big challenge ahead of Khattar is to achieve a scale large enough to ensure that customers don’t travel too much to get their cars serviced. Experts say an ideal model to generate good volume is one where the workshop is within 5 km of the customer’s home or office.

Both Carnation and MyTVS are yet to find a solution to this problem because multi-brand service centres will need high capital expenditure for real estate, tools, machinery, staff and inventory.

One way out is to expand through franchisees, and this is what Khattar has begun. But managing franchisees needs effort. MyTVS has already burnt its fingers.

“We had to get out of the franchisee model because managing them was a tremendous challenge. We found most of them taking short cuts by using spurious parts. So, our brand was getting affected,” says Srivatchan. But if Khattar can standardise processes and identify the right franchisees, then this could be the basis for a rapid scale-up.

As of now, Khattar still has much to prove.

First Published: Oct 19, 2012, 07:03

Subscribe Now