Deepinder Goyal and Zomato: Serving the market

Deepinder Goyal knows what's on order for a profitable Zomato: Online delivery, downscaled global operations and continued big-picture thinking

Promoters of unlisted firms typically, and very politely, decline to share financial details of their ventures. That will not surprise you. They are the norm. And then there is the exception: Deepinder Goyal, who will even do the math for you to explain how Zomato’s numbers are drawn. His now-famous openness—he regularly chronicles his startup’s journey in a blog on the company website—can be a double-edged sword, we are told by people both within and outside the system. Some like his leadership skills, while others call him too blunt for his own good.

The mail that he sent to his ad sales team in November 2015 is an example of this openness. “It was a motivational mail. I write such mails all the time,” he shrugs with a smile, although it was perceived as a visible sign of distress in the restaurant discovery venture at the time. The message, which found its way to the media, was titled ‘Perspective for our sales team’ in the subject line. The co-founder had written that Zomato was “far behind on the numbers” that it had promised to its investors for the year ending March 2016. The team did ultimately meet the target in March (of doubling the revenues), but Goyal had set off the alarm bells seeing the turmoil around. “The market had turned in September,” Zomato’s co-founder and chief executive tells Forbes India. “We had cash in the bank that could sustain us for six months,” he continues. “We had to take several difficult calls otherwise we would put the entire operation at risk.”

Casually dressed in a greyish-blue shirt with sleeves rolled up and jeans, the 33-year-old Goyal could be any other employee in his eight-year-old venture, where the average age is 25. His workspace, usually, is at the corner of a large table in an open office, shared with at least four other colleagues. But, for this interview, we are seated in a conference room at his company’s 22nd floor headquarters in Gurgaon, surrounded by white glass walls that seem to be used regularly as blackboards. The scribbles, though, mean nothing to an outsider, however hard one may try to decipher them.

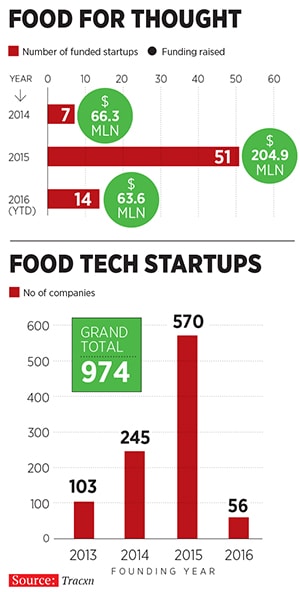

At least a few of them are likely to be linked to the “turn” that Goyal speaks of, which hit the Indian food tech market in 2015, on the back of a record year of investments in the industry (see table on page 39). In 2015, 51 food tech startups raised $204.9 million, as per startup intelligence and market research platform Tracxn’s estimates, in contrast to seven that raised $66.3 million in the preceding year. Instead of strengthening their fundamentals, however, many firms went in reverse order, says Ash Lilani, managing partner and co-founder of Bengaluru-based Saama Capital. “They went out and focussed on building markets and customer acquisition rather than on unit economics. That model is not sustainable in any country unless you have endless capital.” Investments soon dried up, and with no capital to back them as well as the nagging poor unit economics, several startups died a premature death.

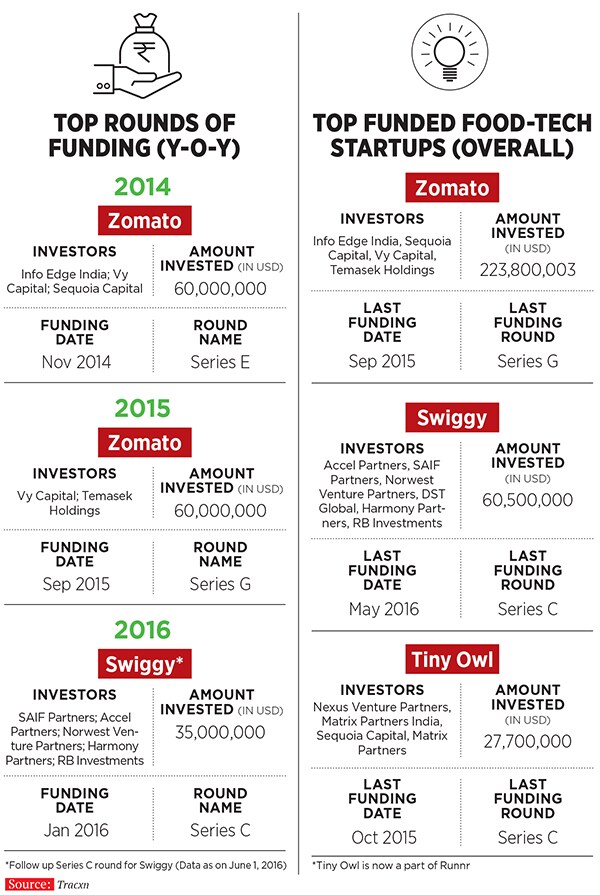

But death affects the living too. And the reverberations of the events of 2015 are still being felt across the sector. Zomato was no exception. The only unicorn in the Indian food tech space, whose investors include Info Edge, Vy Capital, Temasek and Sequoia Capital, also faced the heat—as evidenced by the founder’s mail—and has since been changing rapidly to stay alive and relevant.

The first hint of change—or growing up, if you will—in Zomato is visible when you enter the company’s new office. From a standalone four-storeyed building till about eight months ago, India’s original restaurant-discovery platform is now housed in a posh high-rise where it occupies three floors. It has several big-ticket neighbours, including Apple Inc, American Express and Coca-Cola.

Its transformation, however, hasn’t been limited to an address upgrade. The inability of ad sales—which contributed the lion’s share to revenues—to keep up with mounting pressure from high valuations (hence, investor expectations) has proved to be the trigger for bigger changes at Zomato.

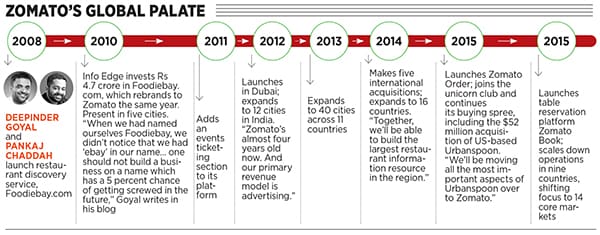

Since inception, Zomato, co-founded by Goyal with Bain & Co colleague Pankaj Chaddah, 30, under the name Foodiebay.com in 2008, had largely depended on an ad-based model, with restaurants promoting their brand on its platform. But that focus has had to change. Earlier in 2015, Zomato launched food-ordering on its platform and, later, began beefing up its B2B tech offerings in an effort to increase its transaction-based business. Then there was the tough decision of scaling down operations—for instance, in October, it shut down Zomato Cashless, its cashless payments business, just eight months after it was launched—or that of letting go over 300 employees.

Not everyone is buying into this transformation, though. In May this year, HSBC Securities and Capital Markets (India) valued Zomato at about $500 million, almost half the valuation at which the company raised its last round of funding in September. The brokerage cited concerns over the company’s advertisement-heavy business model, intensifying competition in the food ordering space and capital-losing international operations for the watered-down figure. Reacting thereafter in a blog post, Goyal pointed out that the report by its own admission was an “outlier” and that this wasn’t a real markdown—the investors still maintained its valuation at $1 billion. “It’s like being the flavour of the month and then falling from the favour. For us, we operate in a portfolio of markets the oldest markets are profitable, and the new markets are not. It’s as simple as that,” says Goyal.

What isn’t as simple is the ongoing restructuring at Zomato, which has a simple but, thus far, elusive goal: Profitability. Losses have widened by 262 percent, at Rs 492.27 crore in FY16 over Rs 136 crore previously, while revenues have nearly doubled to Rs 184.97 crore, over Rs 96.70 crore in FY15. “We are a growing company we are supposed to have losses. That’s the purpose of growth capital anyway. If you were going to be profitable the next day, why would you raise capital?” says Goyal, reiterating the immediate focus on profitability through a leaner, sharper structure.

To reach its goal, Zomato has zeroed in on online food ordering as the new area of focus. It expects that the business can deliver profits in the next 6 to 9 months. The service was started in April last year and currently delivers 26,000-28,000 orders a day, as against 40,000 by market leader Swiggy. But the business has grown by 30 percent month-on-month—it delivered 750,000 orders in May—and the company expects that it will break even at 36,000 orders a day, a target it says is easily achievable.

It should be noted that for a business that has become critical for growth (online food delivery currently constitutes about 20 percent of Zomato’s India revenues), it was a late, even reluctant, entrant to it. And there’s a good reason for that.

Not many know that Goyal had a delivery startup called Foodlet back in 2005. It was a forgettable experience too. The biggest problem he faced was that restaurants would de-prioritise Foodlet’s orders because they came from an aggregator’s customers. The quality of the service, he says, was low compared to direct orders to the restaurant.

Zomato foresaw similar issues in 2011 as well. “We might go into online ordering sometime down the line,” Chaddah wrote in a post on Zomato’s blog, back in 2011. “But with the current state of affairs, if we enable online ordering now, we see ourselves running into problems bigger than the ones we will be trying to solve.” Finally, Zomato bit the bullet in 2015 after a small pilot.

The tardiness proved to be a boon because when they did enter food delivery last year, “they did it from a position of strength,” says Ajeet Khurana, angel investor, mentor and former chief executive of Society for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (SINE), a startup incubator run by IIT-Bombay. “Zomato has had the luxury of seeing the earliest entrants fall, and it has entered the market with a huge user base, which is a strength.” The market today is a saner, more mature version of itself. “What you’re seeing is a rationalisation. People are saying: Let’s get the unit economics right. Let’s try to break even,” says Saama’s Lilani. And it’s not just the food-tech businesses that are becoming more rational. “Consumers have started paying for delivery and restaurants are willing to pay higher commissions,” says Mohit Kumar, co-founder and CEO of Runnr, the newly-formed online food delivery and logistics company (after the acquisition of Tiny Owl by RoadRunnr). “They [restaurants] understand that with increasing real estate costs, delivery is a better business to scale.”

Zomato also conducts delivery operations in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Reason: Foreign markets offer better margins in rupee terms. The contribution margin on an order in India is Rs 20 compared to Rs 50 in the UAE. (The UAE, in fact, is a big contributor to Zomato’s overall revenue, accounting for about 20 percent. India is at 45 percent while the rest are accounted for by the 21 other countries where Zomato had a presence.)

“Our average order value (AoV) in this business (online ordering) is more than 1.5 times the size of our competitor,” says Goyal. It stands at Rs 480 in India. “This makes our business way more viable than pretty much anyone else’s. The AoV multiplied by our order volumes also makes us the largest player by GMV (gross merchandise value) in this market in both these countries (India and the UAE).” About 80 percent of Zomato’s orders are delivered by restaurants, and 20 percent by the company through logistics partners such as Delhivery and Grab.

During an earnings conference call in May hosted by Info Edge, which owns Naukri.com, jeevansaathi.com and 99acres.com, and holds a 47 percent stake in Zomato, Goyal delved deeper into the problems with handling delivery. “We literally make Rs (-)2 on this 20 percent,” he said of the orders that are delivered by its logistics partners. “So we actually lose money in spite of the fact that we have outsourced delivery to someone else and the delivery boys of the companies only cater to food during lunch and dinner and they do ecommerce deliveries during the rest of the day.”

In reply to a question about market share and companies that had shut shop, Goyal again referenced the tough unit economics of the business, saying, “Those guys never even had market share to begin with. However, I would say that even the other guys, the way the unit economics are working, I do not think they would have more than six to nine months left.”

There is, in fact, a debate raging globally as to whether the marketplaces should take control of the logistics (as global player GrubHub is starting to do) or not (like Just Eat does in the US and Canada). The marketplace business model, by its very nature, is high-margin and scalable once dominance is reached. Delivery adds the obvious cost of transportation and makes the model less flexible and difficult to expand, as it requires a large enough fleet during peak hours.Bengaluru-based food aggregator and Zomato’s primary competitor in food delivery, Swiggy, seems to be doing well on the back of its in-house logistics and focus on just a few markets within the country. Nandan Reddy, co-founder, Swiggy, says they want to ensure a friction-less experience to their customers which is possible only when the company controls the ordering and delivery itself. The one-and-a-half-year-old firm claims to be profitable on every order post-delivery in two of the eight cities it operates in. “We have never gone beyond top cities because we feel the biggest chunk of customers is there. We control demand and supply. We are increasing our efficiency it’s important for us to increase our market share,” says Reddy, adding that food tech will be a battlefield of 2-3 players. Swiggy has a delivery fleet of about 5,500 people. It has also introduced a few measures to improve margins: A convenience fee of Rs 20 on the orders delivered as well as surge pricing, a relatively new concept in the food tech space.

In contrast, Zomato has expanded its network to even those restaurants that don’t deliver, thereby increasing the total available market. For such orders, it has collaborations with third-party delivery companies, thereby benefiting from both variability of delivery cost and maintaining control of the delivery experience. “Our value proposition is simple—we bring incremental business for restaurants and convenience for customers. Our competition is dialling in for food,” says the soft-spoken Chaddah, the key driver of the online food delivery business. “We want to be a website that people use two to three times a day,” adds Surobhi Das, chief operating officer of Zomato, who has been with the company for five years now.

The sheer potential for growth has drawn many players to the business, despite its obvious challenges: The online food aggregation business can increase from almost nothing in 2014 to $4.4 billion in 2020 in India, according to a Morgan Stanley research report released in February this year. Margins can be high in this space, the report indicated, by citing examples of global firms such as GrubHub whose adjusted operating margins have been around 30 percent, while Just Eat reported 2014 Ebidta (earnings before interest, depreciation, tax and amortisation) margins of 40 percent in the UK and Canada. Companies such as GrubHub, JustEat and Delivery Hero deliver three meals per second. The velocity, in contrast, is far lower in India, as the on-demand business really started picking up only in early 2015. “We have just scratched the surface,” says the Morgan Stanley report. “Zomato Order currently has tie-ups with 12,000 restaurants, highlighting the headroom for growth in the years to come.”

Clearly, ordering is emerging as the most important part of Zomato’s evolution, but it isn’t the only one. The company recently launched Zomato Book, a table reservations platform. With it, Zomato has entered into competition with EazyDiner and Dineout, and completed expansion into nearly all facets of India’s restaurant ecosystem. “These are a part of the expansion and growth horizontals strategy planned several years ago. We are not moving away from the old business of classifieds and ads. It’s a matter of opportunities that look good,” says Sanjeev Bikhchandani, founder and executive vice chairman of Info Edge.

Zomato’s core proposition of restaurant discovery combined with its software at the restaurant for food delivery, restaurant point of sale (POS) and table reservations ensure that the company has deep roots into one million restaurants across the globe.

In turn, Zomato too seems to be important for restaurants. And one fundamental aspect seems to set it apart. “Zomato is bringing in customers rather than piggybacking on the restaurants’ customers,” says Khurana. This is in contrast to what many startups in the space were attempting to do. Zorawar Kalra, founder and managing director of Massive Restaurants Pvt Ltd, which runs Farzi Café, Masala Bar and Masala Library, says the value-add can be substantial to a business. “It is an enabler. It makes it easy to reach far more customers than you can seat. If you can seat 60, it’ll help you deliver to 60 more.”

While Goyal has spent the past year restructuring the business, he has had to do it under the intense media glare that follows his company. “The one thing that differentiates an entrepreneur is the intuition (and courage) to take calculated risks. Some initiatives will fail and others will propel the company into new directions. Whether it is food ordering, international market expansion, table reservations—Zomato has demonstrated that it has the guts to try new things constantly,” says Mohit Bhatnagar, managing director, Sequoia Capital India Advisors, which invested in Zomato in 2013.

It helps that Goyal is an “overall picture” kind of guy, says Bhatnagar. For instance, when the board advises him to change something in the business, Goyal considers it but does not change even one individual pixel unless he sees the overall new picture. “That’s a great insight into Deepi’s mind, someone who does not lose sight of the forest for the trees,” says Bhatnagar.

It is, perhaps, this need for perspective that has guided Goyal’s recent actions. Zomato has scaled down its operations in nine countries to narrow down its focus to 14 core countries. It will manage those markets (Sri Lanka, Ireland, Chile, Canada, Brazil, Italy, Slovakia, the US and the UK) out of India. This call, of remote management, had to be taken to reduce the cash burn on the high-risk geographies they had ventured into. The month-on-month cash burn is now $1.47 million, compared to $9 million early last year.

Zomato, and its employees, have also felt the burn of churn—of several high-profile exits such as those of chief marketing officer Alok Jain, product heads Namita Gupta and Tanmay Saksena. “It’s not always [interpersonal] differences,” explains Goyal. “It can be performance related also but you will probably never get to know that,” he adds with a smile that he wears almost like a defence. “Our aim right now is attaining profitability, and that’s the only thing we think about.” Even the retrenchment of the 300 employees earlier this year is a part of the process. And of the tumult that is synonymous with the food tech system.

Take the extreme case of the bizarre hostage crisis that unfolded at the offices of restaurant delivery platform TinyOwl in November last year. According to media reports, Gaurav Choudhary, the firm’s co-founder, was restricted from leaving the office by staffers who were being laid off. Then there are examples of downscaling and even complete shutdowns. For instance, the food delivery firm Dazo which discontinued its curated food ordering platform in October less than a year after inception due to lack of funding. Bengaluru-based online food service firm SpoonJoy, which raised $1 million last year, was acquired by on-demand delivery service Grofers. And, in May, Gurgaon-based food delivery startup Yumist shut down its operations in Bengaluru, less than a year after it launched in the city. As for TinyOwl, it was acquired by hyper-local logistics startup, RoadRunnr earlier this year. The two have now combined to form the new entity Runnr, which will focus on food delivery, besides its B2B logistics service.

“This sector is definitely very competitive with very thin margins today and a lot needs to be done to make it sustainable over long term,” says Shashaank Shekhar Singhal, founder of Dazo. Consequently, food tech startups are on the hunt for business models that’ll assure scale and sustainability. There is the fully integrated model or the full stack model which includes Eatonomist, Tummykart, Box8 and Faasos, where the company creates its own menu, controls the kitchen, orders and the food delivery services. Then there is the order and delivery model—where the startup acts not only as a software layer that aggregates restaurants bringing in additional orders but also manages deliveries for them. Think FoodPanda and Swiggy, and now, of course, Zomato.

Will the restructured Zomato see a different, even a mellowed, Goyal? Unlikely, because the boy from small-town India, from Muktsar near Bathinda in Punjab, isn’t in it to win a popularity contest or toe the conventional line.

Let’s recall how, after his struggles in school, even failing class 5, he managed to crack the tough Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) Joint Entrance Examination in his first attempt (both he and Chaddah are IIT-Delhi grads). Stumble and stand firm seems to be a pattern for Goyal. And a repeat seems to be in order for Zomato.

First Published: Jul 20, 2016, 05:54

Subscribe Now