Byju's: Swipe and learn from this near-unicorn

At a time when most consumer internet firms are battling a cash crunch, Byju's is aiming to be India's next homegrown unicorn

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes IndiaByju Raveendran spent the winter of 2005 musing over the promises and perils of entrepreneurship. It was a stable, comfortable time for him. His job as a service engineer at Pan Ocean Shipping was taking him to distant corners of the world, from the Caribbean islands to Spain and, more importantly, bringing home close to ₹50 lakh a year, no mean sum for a middle-class household in Azhikode, a coastal village in the Kannur district of Kerala.

But events had compelled him to ponder the possibilities of a riskier career.

Around August that year, while on a break to meet friends and family in Bengaluru after a 15-month-long voyage, Raveendran—born to school teachers—spent most weekends giving math tuitions to his friends aspiring to crack management entrance tests. He found that, over the next three months, new faces started getting added to his ‘class’. Raveendran went viral on employee forums at technology companies, and chatter around his ability to water down complex mathematical problems to suit anybody’s appetite started getting louder.

That year, Raveendran took the Common Aptitude Test (CAT) “for fun”, scored in the 100th percentile and cleared interviews for the Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) in Ahmedabad, Bengaluru and Kolkata.

He found himself spoilt for choice. “I could have gone back to the job because I was in love with it. I could join an IIM. I could also scale up the tutorials. They [his students] were giving me so much more importance than what I had ever got,” recalls Raveendran, 38, sitting in the conference room of his eponymous company’s headquarters in Bengaluru.Of the three options, he figured that the job and management degree could wait for a while. The business proposition of tutorials made far more sense to him: Consider that some of his students also attended legacy offline tutorials such as Triumphant Institute of Management Education (T.I.M.E) and Career Launcher, which had been in the business for more than 10 years, but were still coming to him to hone their skills. Raveendran gave himself six months to scale up the tutorials.

This was a time when the startup wave was yet to hit Indian shores. Venture capital was a novelty. Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal, who founded India’s largest consumer internet startup Flipkart in 2007, were slogging as software engineers at Amazon Web Services. Bhavish Aggarwal and Ankit Bhati, the founders of ride hailing service Ola, were still in college.

Raveendran quit his job in early 2006 to dive into teaching full-time. The sessions, informally called Byju’s classes, and this time for a fee, migrated from his friend’s drawing room to a 35-seater classroom. Within two months, he was teaching math, data interpretation and logical reasoning for management entrance tests to 1,200 students in an auditorium in Bengaluru.

Over the next decade, his management entrance tutorial metamorphosed into the largest homegrown online education company for K-12 students, Byju’s (christened thus in November 2011), with ₹260 crore in revenues (FY17). Raveendran now claims gross sales of ₹50 crore a month, which will take the company close to ₹600 crore in revenue this fiscal. “We will become profitable this year. And if we go for another fundraise, we will be a profitable unicorn,” he grins. A commendable feat, if achieved, since India is yet to see a profitable consumer internet startup at scale.

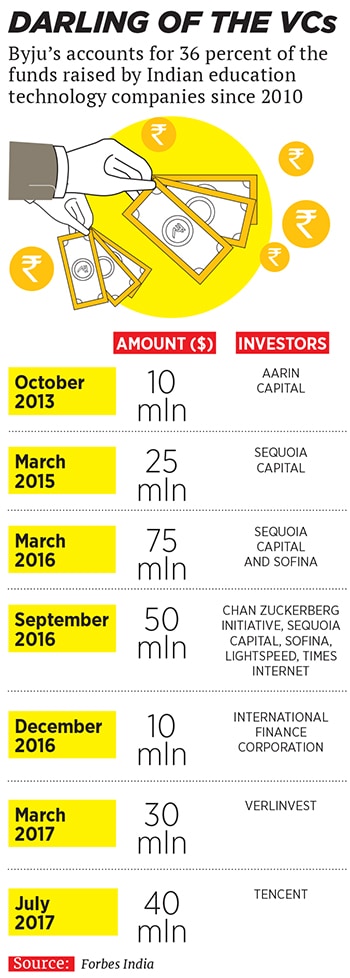

All these and more have made Byju’s India’s most valuable online education company at ₹5,000 crore (about $780 million). Of the approximately $240 million that the company has raised in equity and debt, about $205 million came between March 2016 and July 2017 when most consumer internet startups were heading back to the drawing board to chart out frugal business plans amid a protracted lull in funding. Yet, Byju’s snared funds from Tencent Holdings and Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the personal project of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan.

“The valuation of Byju’s has grown because of lack of supply. How many companies are showing this kind of revenue growth and a clear path to profit? It is good quality revenue, predictable and repetitive, almost similar to a software-as-a-service (Saas) business. If Saas companies are getting valued at 10 times their annual run rate, then why not Byju’s?” says Vinod Murali, managing partner at Alteria Capital Advisors, a venture debt firm.

The fortuitous plunge into entrepreneurship has led to a surge in Raveendran’s personal fortunes as well. Until March 31, 2017, Raveendran’s 26 percent holding in the company was worth ₹1,079 crore, according to Tracxn, a company which tracks startups. His brother, Riju Raveendran, and wife, Divya Gokulnath, held 12.3 percent and 7.5 percent respectively.

“The CAT is beneath you,” Pravin Prakash recalls Raveendran telling an auditorium full of ignited minds raring to storm through the hallowed portals of the IIMs. Prakash was one of them. Raveendran maintains this was not arrogance, but confidence speaking because he knows his subjects inside out. Growing up, he could be spotted more often on the playground than inside classrooms at the Azhikode Government High School, but still won the math Olympiad at the age of 14. Team Byju’s: (From left) Mrinal Mohit, Pravin Prakash, Divya Gokulnath and Vinay MR (seated)

Team Byju’s: (From left) Mrinal Mohit, Pravin Prakash, Divya Gokulnath and Vinay MR (seated)

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes IndiaRaveendran made it a point to learn math beyond the prescribed syllabus. His fascination for numbers made him keep a count of the steps he took every day, long before fitness apps became a rage, and even calculate the speed of a moving train, among other quirks.

“Sounds difficult? It is simple. Keep an eye on the mile posts and be patient [enough] to calculate the time taken to cross two such posts. As a child, I was fascinated by numbers and math, which is beyond a subject for me. I just capitalised on my love for math,” he says.

His teaching technique manifested this passion. “My classes became popular because I was giving the students methods that were easy to comprehend and appealing. It was not about teaching how to solve a set pattern of 20 questions, but teaching a concept in such a way that they could answer any question on that topic,” he adds.By mid-2006, barely six months after starting up, Raveendran was travelling to Chennai, Mumbai and Pune to take classes, some in auditoriums, others on college campuses. By the end of 2007, Raveendran, who says he never attended a coaching class while growing up, was travelling to nine cities every week, thanks to the “cheap Air Deccan flights”.

By 2008, Raveendran had managed to sell his dream to a few of his students, who joined the business full-time. Today, Prakash is the chief marketing officer at Byju’s, Mrinal Mohit is chief operating officer, Vinay MR chief content officer, Divya Gokulnath, Raveendran’s wife (and former student), a director at the company and one of the 10-odd teachers. Anita Kishore, the chief strategy officer, joined full time in March 2014.

Around the same time, the dream run of the first two years was at the risk of getting stymied. Growth had flattened, despite close to 2 lakh aspirants taking the CAT every year. The students were spread across the country and Raveendran could travel only so much.

The team got into a huddle to devise a turnaround, and came up with this: Raveendran would record his lectures, which would then be played on large screens in auditoriums. He would be present during the first session, as it was important to put a face to the name. The strategy worked. In the next few months, Raveendran’s recorded classes were being beamed in 40 centres across the country. But he had the appetite for more. “Between 2009 and 2011, there wasn’t much growth because CAT was a niche subject. So we created more products… GRE, GMAT, IAS, etc,” says Raveendran. However, all told, revenues for FY12 stood at ₹4 crore.

Around late 2011, Raveendran had identified the next growth driver for his business: K-12 education. According to a 2012 report by the ministry of human resource and development, in 2010, India was home to approximately 100 crore children aged between six and 17. Of them, about 25 crore were enrolled in school between class 1 and 12, almost 10 times the 2.6 crore students who opted for an education after high school, essentially Raveendran’s target audience until then.

Simultaneously, India was on the cusp of an internet revolution. A report by the Internet and Mobile Association of India estimated 112 million internet users in India by September 2011. More than 48 percent of the total internet usage would be driven by school and college goers, potential consumers for Raveendran’s products.

He promptly replicated the CAT tutorial template for school students, holding classes in auditoriums. (Only this time, he knew right from day one that the entire business would move online in the next couple of years.) The plan was to initially roll out products for classes 8 to 12, before branching out to the lower grades.

“Generally, parents open up their wallets from class 8 onward. That is when panic starts setting in. There is a lucrative market, but that market is at the latter end of our study cycle. Early on, one can do a lot of things but there is no outcome to justify the massive spends. Before class 8, parents would rather buy their children a pair of Levi’s jeans, for instance, than a subscription for Byju’s,” says Deepak Natraj, managing director at Aarin Capital. “[But even so] the lower grades are equally important. If you are hooked on to the platform early, you are a lifelong customer.”

By Raveendran’s own admission, the company spent the next three years between 2012 and 2015, away from the “spotlight”. These years were marked by a frenetic pace of activity to develop video content for the K-12 segment. A few hundred media, content and technology professionals spent hours developing teaching modules and content that would appeal to a young audience. It could either be a teacher pulling a pizza out of thin air to explain properties of a circle or another, strapped in a parachute, jumping off a cliff to demonstrate gravity. The videos were played back to the students in tutorials for feedback.Most of the revenues from the offline tutorials—₹12 crore in fiscal 2013 and ₹21 crore the next—were ploughed back into the business to churn out more and more videos.

“Children associate videos with movies like Cars. Our videos need not have been the same quality as Disney, but they had to come close. K-12 was not a short-term strategy for us to build numbers,” says Raveendran.

This exercise required more money. A chance meeting with Manipal Group Chairman Ranjan Pai, who is also the founder of venture capital firm Aarin Capital, provided much-needed relief. In October 2013, Aarin Capital invested ₹50 crore in Byju’s at a valuation of ₹200 crore. “That money helped us accelerate. Else we could not have completed the online transition by 2015,” says Raveendran.

The foray into the K-12 segment has paid off it currently accounts for close to 85 percent of the company’s revenue. And much of the success came after the launch of the app in August 2015.

Today, Byju’s operates a handful of classrooms for K-12 students in Delhi, Bengaluru and Chennai, acting as physical touch points for those who are yet not comfortable with online learning. The offline business generated about ₹20 crore in revenue in FY17. “We will not increase the number of such centres and focus online instead,” says Raveendran.

The app has proved to be a game changer for Byju’s, and its success can be attributed to both content and design. Raveendran has made sure that the videos are not the usual recording of a classroom session by a straight-faced teacher. Also, a student cannot afford to move from one chapter to another without taking tests, which ensures high engagement. “Besides the kind of reach you get with an app is not possible with any other medium,” explains Raveendran.

In the two years since, Byju’s has acquired more than 5 lakh paid users, adding about 55,000 subscribers a month. Close to 90 percent of the paid consumers renewed their subscription in the last two years, which is not surprising, given that children on an average spend 40 minutes a day on the app.

More importantly, about 70 percent of the paid users live outside the top 10 cities, which lack established private tutorials especially for students between classes 3 and 8. Byju’s not only caters to ICSE and CBSC syllabii, but also Kerala, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh state boards.

“Where Byju’s secret sauce lies is it has cracked the content piece well. By making the content neutral, it has made it appealing to the regional audience,” says Kunal Walia, managing partner at Khetal Advisors, an investment bank.

Such numbers and a long list of enviable investors—Aarin Capital, Sequoia Capital, Sofina, Lightspeed Venture Partners, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, International Finance Corporation, Verlinvest and Tencent —make Byju’s a breakout in the segment. The cash crunch has taken a toll on the businesses, prompting 102 of them to shut shop between 2012 and 2017, according to Tracxn. More than half of them, about 58, fell by the wayside in 2016 alone, when venture capital funding in India hit a rock bottom. Among the casualties were Intel Capital- and Jafco Asia-backed Vriti and Norwest Venture Partners-backed iProf.

Others, including Educomp Solutions, have taken a significant hit in business, according to a Forbes Asia report. Shantanu Prakash, founder and chairman at Educomp, who was worth $920 million in 2009, has seen his wealth erode to about $10 million in the next eight years. His company, which mainly sells digital content and equipment to schools, is currently reeling under a debt of $320 million after several institutes failed to pay up.

Out of the 3,112 ed-tech startups founded in India since 2010, about 10 percent have managed to raise a cumulative $687 million in institutional funding. Byju’s accounts for more than half of the $415 million invested in ed-tech startups in India since 2015, when it launched the app. Byju’s is also among the top-10 best-funded online education startups globally, along with iTutorGroup and Hujiang in China, Everfi in the UK and HotChalk in the US.

Dev Khare, managing director at the India arm of Lightspeed Venture Partners, describes Raveendran as a “force of nature”. A force magnetic enough for his firm to invest close to $20 million in Byju’s at a valuation of about $300 million in May last year to partially buy out Aarin Capital, a far cry from Lightspeed’s philosophy of catching a company young.

“It is unusual to see a company such as Byju’s, where you can expect huge returns despite coming in at an advanced stage. When I first met Raveendran, I left with the view that he had clarity of purpose. The revenue stands out as compared to other businesses in this segment. It created this market (online K-12 education) in India,” says Khare.

Now, Raveendran wants to evolve the app into every child’s private tutor. The plan is to launch interactive videos and personalise content. Personalisation would replicate the offline experience of a one-on-one interaction with a tutor, to the extent that the app will gauge a child’s strengths, weakness and learning pattern and serve content accordingly.

“We map a child’s knowledge graph. When the child interacts with any piece of content, we are gleaning information that will help us suggest what a child should be doing for a different outcome. We can address the learning gaps. Otherwise the gaps will fester and hurt you later on. Personalisation will be core,” says Ranjit Radhakrishnan, chief product officer at Byju’s.

It is not just the product that has made Byju’s click with students and their parents. It takes a lot to make parents pay ₹10,000-₹15,000 in annual fees for supplemental education. Aggressive marketing campaigns are relied on. Last year, Byju’s spent ₹70 crore on marketing while this year the company will spend ₹80-₹100 crore. Add to it an aggressive sales team: “We hire engineers at ₹6-₹7 lakh per year. They have a good level of academic understanding. We need sales guys who can talk math and science and not offers or discounts,” says Raveendran.

He has global ambitions as well. Byju’s will launch an app in English-speaking markets such as the US and the UK among others in May next year, for pre-nursery to class 3 students. Raveendran is flying in teachers from the local markets to record videos at his Bengaluru office.

“The likes of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and Tencent are big names globally and is a big validation for a lot of people to work with us,” says Raveendran. In July, Byju’s bought Pearson Plc’s Edurite and TutorVista, which has a presence in the US. It had earlier bought career guidance and academic profile builder Vidyartha and mobile learning platform provider Specadel Technologies. More acquisitions will come for the global push, says Raveendran.

While the euphoria seems justified, investors say it is too early to celebrate. With mammoth fundraises and storied investors on board, Byju’s can ill afford to remain an interesting $800-million company, says Alteria Capital’s Murali.

“The kind of capital that has gone in means it has no choice but to become a multi-billion dollar company to make it worth everybody’s while. Byju’s now has to return a significant amount, which means progressively, there will be an inorganic approach as well. That to me is one potential challenge. A large acquisition comes with its own risk,” says Murali.

Besides, Byju’s cannot ignore competition from well-oiled legacy businesses such as Brilliant Tutorials, Forum for Indian Institute of Technology and Joint Entrance Examination (FIITJEE), Bansal Tutorials and Aakash Institute among others, who target students in classes 11 and 12, preparing for entrance tests to engineering and medical colleges.

Raveendran is confident that a global push, sharp focus on the product, deeper penetration into India and a tight grip on spends will make Byju’s a force to reckon with, internationally. That apart, the online education market in India is poised to explode in the next four years. According to a May 2017 report by KPMG and Google, India’s online education market is expected to grow to $1.96 billion and about 9.6 million users by 2021 from $247 million and about 1.6 million users in 2016. “I may have started the business by chance, but we aren’t where we are by chance,” he says.

First Published: Sep 21, 2017, 06:38

Subscribe Now